‘Genocide in colonial Queensland, Australia‘, Honest History, 26 May 2017

The attached pdf is a revised and extended version of the prologue to the author’s 2013 book, Conspiracy of Silence: Queensland’s Frontier Killing Times. Honest History thanks Timothy Bottoms for making it available. Normally, in a document of this length we would provide illustrations to accompany the text, or ask the author to do so, and we might make some ‘house-style’ edits. On this occasion, however, illustrations would have been superfluous; the words speak for themselves. Honest History thanks Timothy Bottoms for making the material available. (There is now a video version of Conspiracy of Silence.)

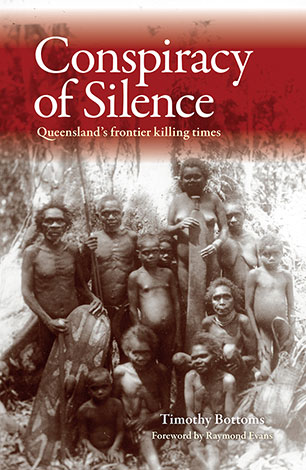

Cover of Conspiracy of Silence (2013)

Cover of Conspiracy of Silence (2013)

Bottoms tracks how early denialism about frontier violence turned gradually into a willingness to talk and write about it. There has, however, been ‘selective amnesia’ over time and the numbers killed are still uncertain.

What was omitted from the original prologue in Bottoms’ Conspiracy of Silence, but which appears here, was his detailed comparison of what happened in Queensland with the eight stages of genocide recognised by the international organisation, Genocide Watch.

All of these stages [Bottoms says] can be found in the history of the Australian colonies, and in particular Queensland … Put simply, genocide is “the criminal intent to destroy or cripple permanently a human group” [Raphael Lemkin], and as Larissa Behrendt, an Aboriginal scholar has observed: “the political posturing and semantic debates do nothing to dispel the feeling Indigenous people have that this is the word that adequately describes our experience as colonized people”.

Bottoms traces how the conspiracy of silence about these events developed and argues:

This form of selective forgetfulness or outright disinformation, amnesia or a conspiracy of silence, still pervades our national character. What is more, it continues to deny Aboriginal Australians their rightful place in the nation’s identity.

The ‘Pioneering Myth’, describing an apparently peaceful filling up of the country by settlers, helped to fill the silence.

Bottoms provides a map showing dozens of massacres, including a few perpetrated by blacks against whites. Most importantly, though, the final couple of paragraphs of Bottoms’ piece are particularly relevant, first, to the Honest History project and, secondly, to an argument often put about how, even if these events happened, they were not the fault of modern, predominantly Anglo-Celtic Australia, and thus can be put out of mind.

Defining the orchestration of the “killing times” as genocide is extremely challenging for contemporary Australians, however, when assessed in relation to the international eight stages, it leaves no doubt, that although the term “genocide” did not exist then, the actions of the colonial Queensland Government and elements of the settler society were in fact implementing a policy of genocide.

That this policy was then hidden and papered over is particularly pertinent in the context of what we as a nation portray as being a part of our national character – being honest or straightforward. If we are to have any integrity as a nation, let alone as individuals, it is appropriate for us to recognise the unvarnished truth about our past.

This is somewhat problematic in the current political climate (2017) where gulags for refugees are acceptable to both major parties. Yet despite this and our nation’s parsimonious approach towards our First People, there has been a gradual move in perceptions and a growing acceptance, although grudgingly, of the truth about violence on the frontier.

We would do well to remember that: “No Australian today is responsible for what

happened on our colonial frontier. But we are responsible for not acknowledging what

happened. If we do not, our integrity as a nation is flawed…” [Conspiracy of Silence, p. 207].

Read more of the Timothy Bottoms piece …

See also: other material from Timothy Bottoms on the Honest History site, on the Myall Creek massacre, and on the history of Cairns, North Queensland; the research of John Connor, Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen; Paul Daley’s chapter (‘Our most important war: The legacy of frontier conflict’) in The Honest History Book (long extract here); material under our First Peoples thumbnail, particularly links to pioneering work by Humphrey McQueen and to the work of Henry Reynolds.

The chapter by Larissa Behrendt (‘Settlement or invasion? The coloniser’s quandary’) in The Honest History Book concluded thus:

Until we bury the myth that Australia was “settled”, we can never become a country where all Australians see Indigenous history and culture as a key part of the nation’s history and culture – and until we do that we will never have found a way to truly share this colonised country.

Timothy Bottoms (Treaty Republic)

Timothy Bottoms (Treaty Republic)

The word ‘settled’ is too benign a description of what happened in Australia after 1788. ‘Colonised’, with its connotation of gaining and exercising control over the original inhabitants, gets closer. The reluctance of some of us to use the word ‘invasion’ in the Australian context is perhaps influenced by pervasive images of D-Day 1944: because our invasion lacked an 82nd Airborne Division and 25 000 other troops charging ashore does not mean its effects were less profound or less lasting. (Despite the D-Day analogy, many of us are still reluctant to call what happened on 25 April 1915 an ‘invasion’.)

The invasion of Australia continued at least until the last recorded massacre (Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928) and, it could be argued, it still continues in different forms. In the conclusion to The Honest History Book, Alison Broinowski and David Stephens said this: ‘That invasion of 1788 and its consequences deserve far more of our attention today than do the failed invasion of the Ottoman Empire in 1915 and our military ventures since’. In 2017, when there is still noise abroad in our country about Bullecourt and Passchendaele, the Coral Sea and Beersheba – all of them tragedies for Australians and others – it is well worth keeping in mind other tragedies which actually occurred on our own wide brown land – like those documented by Bottoms – and whose effects are still deeply felt here. To coin a phrase: Lest We Forget.