‘Clare Wright’s You Daughters of Freedom is a Big Book about Big Ideas’, Honest History, 7 October 2018

Diane Bell reviews You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World: Democracy Trilogy, Book Two, by Clare Wright

‘Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.’ (Frederick Douglass, 1857)

With this telling epigraph, Clare Wright announces she is embarking on an epic historical retelling of a key foundation story of the Australian nation. It will demand interrogating the stories we may like to tell ourselves about our origins; reinstating the women of courage, vision and determination who challenged established power structures at local, national and international levels; mapping the contours of the conflicts, collaborations, contradictory and contrary permutations of the diverse organisations that campaigned for the vote; laying bare the brutality of law enforcement licensed by the dogged sexism of their masters.

With this telling epigraph, Clare Wright announces she is embarking on an epic historical retelling of a key foundation story of the Australian nation. It will demand interrogating the stories we may like to tell ourselves about our origins; reinstating the women of courage, vision and determination who challenged established power structures at local, national and international levels; mapping the contours of the conflicts, collaborations, contradictory and contrary permutations of the diverse organisations that campaigned for the vote; laying bare the brutality of law enforcement licensed by the dogged sexism of their masters.

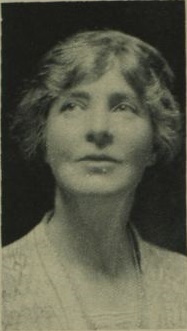

I like to imagine Clare Wright has Douglass’s epigraph embroidered on a bespoke banner hanging in her study. I conjure its provenance: born of meticulous scholarship; nurtured by a talented storyteller; enlivened by the suffragettes’ colours; confident in its reach. Perhaps the hanging recalls the flag of which Wright wrote in her Stella Prize-winning The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka (2013). The hanging most certainly celebrates artist Dora Meeson Coates’s banner, first held aloft in a ten thousand strong women’s march to the Albert Hall in 1908, as the enfranchised daughters of empire brought to the British campaigns their experience and expertise of achieving the Vote for Women. Three years later, the banner was carried in the 1911 Women’s Coronation Procession. By then its meaning had changed: no longer the innovative painting in oil on canvas in the classical style of the day, no longer a diplomatic missive (pp. 244-45), this banner was from a nation that had ‘reverse-colonised the landscape of ideas’ (p. 451).

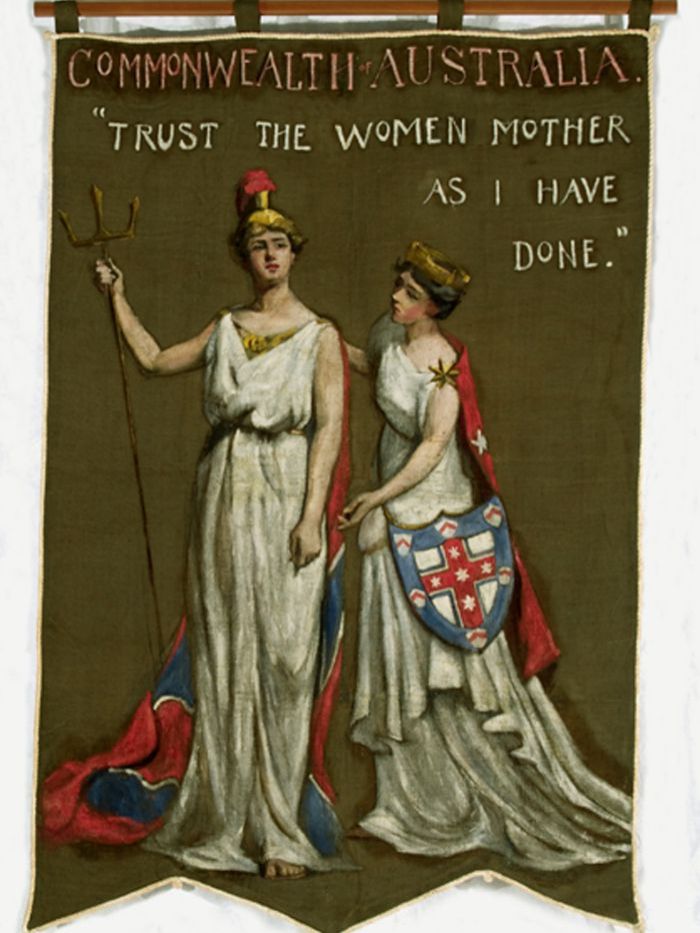

Wright weaves the story of the ‘Women’s Suffrage Banner’ through her carefully crafted account of demands, concessions and ceding of power. Its multi-vocal symbolism informs each chapter in this account of the social laboratory of the newest democracy. Wright knows material objects matter. Banners hung from upstairs windows, banners carried for hours in mile-long processions. Powerful political moments: women’s work, women’s ideas. Dora’s remarkable banner required four people to carry it. Under the gold lettering of ‘Commonwealth of Australia’ stands the white-gowned Mother Britannia holding her sceptre, while Daughter Minerva, who holds the heraldry of the newly federated Australian states, counsels ‘Trust the Women Mother As I Have Done’.

Dora Meeson Coates (GJ Coates/Wikipedia)

Dora Meeson Coates (GJ Coates/Wikipedia)

Between the agenda-setting introductory chapter and the updating of the travels of the banner in the concluding chapter, in three substantial parts – Purity, Courage and Hope – Wright documents the demands on power wrought by her key five characters and does so by taking the reader on site. We are there as the brave, imaginative, defiant deeds and words of Vida Goldstein, Nellie Martel, Dora Montefiore, Muriel Matters, and Dora Meeson Coates are played out at home and on the world stage. We join in their anticipation, frustrations and achievements, cringe as the sexist mantra that their detractors and opponents utter echoes down the generations. Wright draws on a wide range of materials and her use of primary sources is noteworthy. Facts do matter, then and now.

Throughout, Wright is posing critical questions faced by the newly crafted Australian democracy, one that was the envy of the world, one where white women were constitutionally indistinguishable from men. But First Peoples? Wright is clear that the ‘New Dawn’ being proclaimed by the federating states was not ‘untainted by the history of bondage’. This was no ‘free birth’.

The metaphors of purity and danger, for a bright future emerging from a dark past, came thick and fast, communicating something that generally went unspoken, but which the Ovens and Murray Advertiser (5 January 1901) articulated in its coverage of the ‘Dawn of Australian Unity’: ‘Very few of the aboriginals are left to witness this our crowning day, to witness the triumph of the white race …’ It was, of course, demonstrably untrue that Australia’s First People had all ‘died out’. But why let the facts get in the way of a good origin story (p. 20)?

State by state, Wright follows the divergent and intersecting paths pursued by the daughters of freedom. First, the ‘Shrieking Sisterhood, Victoria, 1854-1900’. Vida Goldstein, educated at Presbyterian Ladies College and later through Charles Strong’s independent ministry at the Australian Church, where she saw at first hand the violence and misery of slum houses, she developed her ‘zeal for social reform’ (p. 31).

Vida Goldstein, c. 1914-18 (Wikipedia)

Vida Goldstein, c. 1914-18 (Wikipedia)

In ‘Sydney, 1891’ we meet Mrs Dora Montefiore, a widowed mother of two, luckier than most in having some resources, who, nonetheless, found her privilege did not protect her from laws that gave her no legal custody of her children. She met other women in similar situations. ‘We discussed, and rebelled, and longed to make things better for our children … An economic recipe for change (p. 43).’ Dora decided to form a suffrage society.

In South Australia, there was Catherine Helen Spence with her proposal for proportional representation that had found favour with John Stuart Mill. There was Mary Lee, a widowed mother of seven, favouring direct action; writing incendiary letters; earning a ‘reputation as a shrew’ (p. 52), who linked suffrage to improved working conditions for women. She established the Working Women’s Trades Union of South Australia. Pay particular attention to the confluence of factors (part strategic, part mischief) and the varied talents of the actors (inside and outside the ‘tent’) that delivered the franchise to all South Australian women – yes, Indigenous women were included (p. 57). It was a coup that had ramifications for the federal conventions that shaped the Australian Constitution and Wright’s in the moment account is enriched by her use of first-hand accounts, media reporting, and parliamentary debates.

On the international stage, at the First Conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, 12 February 1902, at the Georgetown Presbyterian Church in the United States, Vida Goldstein joined elder stateswoman Susan B. Anthony and delegates from Norway, Chile, Turkey, Russia, Canada, England and Sweden. She was hailed as ‘the most stunning example of the New Woman: single, independent and, like her country, self-governing, “civilised” and white (p. 103)’. Her lecture circuit was widely reported; her analysis of US democracy relevant today; her parting exchange with Anthony touching and to the point (p. 111).

Back in Australia the ‘purity and danger’ debate regarding the place of the ‘Aboriginal race’ was ‘passionate, fiery and breathtakingly candid’ (p. 121). I would add ‘prophetic’. The Commonwealth Franchise Act received royal assent on 12 June 1902: a victory for white women; an entrenching of 19th century racism for the new nation.

Dora Montefiore 1909 (Progressive Woman/Wikipedia)

Dora Montefiore 1909 (Progressive Woman/Wikipedia)

The ‘Modern Eve’ could vote and stand for office. Would she? On Polling Day, women turned out in large numbers. They voted, more along class than gender lines (p. 156). It was the labour movement, rather than women candidates, that was the victor of the 1903 election (p. 158). Vida had put up her hand. Her platform was protectionist; opposed to capital punishment; advocated a proper water conservation system for the nation; and heartily supported the Immigration Restriction Act (pp. 142-43). Then Nellie Martel entered the fray with a focus on the age of consent – for her a question of class as well as sexual equality (p. 147). She was lampooned and embroiled in a side-bar controversy, even before her platform that included water conservation, equal pay, and good laws for women by women was announced. The Truth newspaper had a field day: low gossip and high politics as ever fuelled its reporting. Although no woman was elected, the 51 497 votes Vida Goldstein received could not be discounted. It was not until 1943 that the first women were elected to the Australian Parliament and, to Vida’s dismay, neither of the candidates had called herself a feminist (p. 475).

In ‘Part Two: Courage’ the action moves to London. We are there on a mild spring day in May 1905 for the third reading of the Women’s Enfranchisement Bill which, like the previous 17 attempts, was thwarted. The women there to hear the reading were exasperated. Seated behind a grille in the Ladies Gallery with only peep-hole sight lines to the speaker, they could be neither seen not heard. Enough. Led by Nellie Martel, they convened outside and drafted a declaration of no confidence in the government (p. 170).

‘The siege of Hammersmith’, June 1906, a play within a play, starred Dora Montefiore who refused to pay taxes if she could not vote. The tax collector came. The bailiff came. Furniture was seized and auctioned. She covered her tax bill. She made a fine speech. Her civil disobedience was a brilliant publicity stunt. Her hand-stitched banner on display at her residence read: ‘Women should vote for the taxes they pay and the laws they obey’ (p. 198).

‘Show us a general demand for suffrage amongst ordinary women’, the government had challenged. And show ‘demand’ they did. ‘Suffrage Saturday’ was a triumph but Prime Minister Asquith was not impressed. The WSPU (Women’s Social and Political Union) upped the ante: revolution and militant action would be needed. The constitutionalists, the NUWSS (National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies), preferred politely sought reform (p. 259). Frustration was mounting: being disruptive and disobedient gets one just so far. It’s a dilemma that bedevils progressive social movements and Wright’s documentation and analysis of the fault lines, including the Pankhurst matri-line, of the early 20th century campaigns, is important case material.

Nellie Martel (Spartacus Educational)

Nellie Martel (Spartacus Educational)

And then there was Muriel Matters, ‘that daring Australian girl’, the first woman to speak in the British Parliament, who locked herself to the Ladies Gallery grille (p. 274ff). Still attached, she and Helen Fox had to be removed, bodily, so the chains could be filed off. Powerful symbolism: a casting off of chains. Rather than pay her fine, Muriel Matters joined the 30 other prisoners in Holloway – not for the grille stunt but for ‘wilfully resisting police’ (p. 277). Muriel’s next piece of theatre was her plan to drop from an air balloon 56 pounds of handbills on the state procession of the King to open the winter session of parliament (p. 291). What could go wrong? The British weather? The balloon was blown off course and the bills jettisoned. The media loved it: ‘A Lady Who Cannot be Kept Down’ (p. 294).

Back in Australia, election day, 13 April 1910, this time Vida Goldstein polled 54 000 votes. This was not enough to get her into the Senate but she had split the Liberal vote. The 49.97 per cent vote for Labor owed much to women electors. They had been instrumental in electing the ‘first Labour government in the world into office’ (p. 311) and they made good the shining hour in advocating female-friendly policies.

Muriel Matters was determined to get support for her British colleagues where battle lines were drawn. Black Friday, 18 November 1910, was the culmination. When Asquith advised the King to dissolve parliament, it was clear there would be no vote on the suffrage resolution. Emmeline Pankhurst called an end to the truce that had held since the King’s death (p. 345). The women marched in battalions to the Commons. Winston Churchill’s instruction to the police that there were to be no arrests was interpreted as licence to assault the hundreds of women trying to get to the steps and present their petition to Asquith. Wholesale brutality ensued (pp. 346-47).

In ‘Part Three: Hope’, Wright takes the reader to the ‘Greatest Procession Known in History’, the ‘Coronation Procession’ of London, 17 June 1911, Suffrage Day. Hope indeed. The year of the coronation of King George V would be the year of the ‘emancipation of the women at the heart and centre of the Empire’ (p. 439). The planning had been intense for 40 000 women, 1000 banners, 100 female marching bands, and 28 societies. Horses, floats. Costumes. And the colours, everywhere, the colours (pp. 439-40). The Australian and New Zealand delegates were given pole position. There were 700 women wearing white frocks as the prisoners’ pageant, one for each woman incarcerated in the struggle for the vote (p. 441), a historical pageant, representations of empire, the societies, and bringing up the rear, men’s groups.

Muriel Matters 1924 (Wikipedia)

Muriel Matters 1924 (Wikipedia)

There had been significant divisions, especially with respect to the role of militancy in achieving the vote, but the procession was a show of sisterly solidarity. There was no violence, no arrests. The media and public were enthusiastic. But how would Asquith respond (p. 445)? In November 1911, he announced a Manhood Suffrage Bill – and thus began the period of letterbox fires, smashed windows, torched hedges, stones not banners (p. 459). The Cat and Mouse Act – a revolving door of gaolings, hunger strikes and force-feedings, release when near death, re-arrest when recovered (p. 450). Emily Wilding Davison, who was arrested nine times, endured seven hunger strikes and was force-fed almost 50 times, became the first martyr of the movement when she threw herself in front of the King’s horse, 4 June 1913, at Epsom (p. 460). And the vote? It was women’s service in World War I, not suffrage activism, that was the official reason for the passage of the Representation of the People Act 1918 (p. 463).

And how is this complex international tale to be told? By whom? To what ends? Wright reminds us that Prime Minister Fisher, who had declared that Australia would follow Britain into war until the last man, had also told a captive London audience that a true democracy can only be maintained honestly and fairly by including woman as well as men in the electorate of the country (p. 466). Australia’s daughters led the world. The Gallipoli story, ‘with its militarist narrative of youthful sacrifice, not youthful optimism’, Wright opines ‘was not the birth of the nation. It was the death of the nation we were well on the way to becoming (p. 466).’

And so to the new Parliament House, Canberra, where Wright guides us through the corridors of power, past monumental artwork, past the prime ministers’ portraits, past the 1963 Yirrkala bark petitions, to the banner of artist Dora Meeson Coates. The banner was rediscovered in the mid-1980s in a large collection of suffragette memorabilia in a Fawcett Library storeroom, and the only clue to its provenance was the ‘Commonwealth of Australia’ lettering at the top. Dale Spender, an Australian feminist living in London at that time, Senators Susan Ryan and Margaret Reynolds each had a hand in its ‘return’ – a valuable item for the bicentennial year. Prime Minister Bob Hawke celebrated the handover at the Lodge on International Women’s Day, 8 March 1988. Dale Spender was commissioned to prepare an educational kit for schools which she duly did, and there it ended. Why? Too radical, too international? (pp. 471-72).

I still have some of my correspondence with Dale Spender from that fateful year and the reception of women’s contributions to the problematic ‘celebration’ of the nation. In 1988, I was Professor of Australian Studies at Deakin University and author of the Australian Bicentennial Landmark volume on women in Australia. In Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters, I traced the transmission of objects (books, plants, sewing machines, jewellery, recipes) across generations of women; and wrote of the stories, values, skills and so on the objects carried. Banners were part of the year. I was delighted when invited to launch the ‘Textile banners and posters for the labour movement’ as part of ‘Art and the shared belief’ at the Exhibition Building, Melbourne, in March 1988 (p. 469). The banners were marvellous but how sad that the Women’s Suffrage Banner was not there.

Dora Meeson Coates’s banner (ABC/Parliament of Australia/NMA)

Dora Meeson Coates’s banner (ABC/Parliament of Australia/NMA)

Rather than writing this review, I had considered cranking up my faithful Singer sewing machine and running up a banner to hang with Douglass’s epigraph: ‘Power erases that which it fears’, an appliqué of heritage fabrics from my maternal grandmother’s workroom. The accompanying note would read: ‘Lest our founding objects and the stories they carry fall into desuetude’.

You Daughters of Freedom is a Big Book about Big Ideas and I have only had the space to highlight a few in this review. There are many more protests, people, proclamations, resolutions, organisations and by-ways to be found in Clare Wright’s book. I urge you to read it; share it with your family, friends and colleagues; make sure your local library has multiple copies; ditto the local book store and newsagent; put it on the list for your reading group. Celebrate the artefact. Objects matter and this one is a handsome book resplendent with its gold lettering and its white, green and purple sash. Read it on public transport. Start a conversation. It’s one we, as a nation, need to be having. Again.

* Diane Bell is a feminist anthropologist, award-winning author, and social justice advocate who has published widely across a number of fields and genres. Her books include Daughters of the Dreaming (1983, 1993, 2002); Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters (1987); Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: A World That Is, Was and Will Be (1996, 2014); Evil: a Novel (2005); and Listen to Ngarrindjeri Women Speaking (2008). She has held senior positions in higher education in Australia and the United States, undertaken a range of consultancies for community-based entities and, after retiring as Professor Emerita of Anthropology, George Washington University, US, returned home to Australia. She currently lives, researches, writes and strategises in Canberra where she is a Distinguished Honorary Professor in the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University. She has contributed a number of pieces for Honest History: use our Search engine.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.