‘Writing about war: the (mostly British) Great War poets’, Honest History, 2 November 2013

Introduction

Anthem for doomed youth (Wilfred Owen)

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Wilfred Owen, who wrote the lines above, is today remembered as the poetic personification of World War I trench warfare as bloody futility. However, when war broke out in August 1914, many poets wrote in praise of patriotism and the glory of war, the noble duty of Youth to die in battle.

The Prime Minister of Australia William Hughes and six unidentified officers: Australian Official Photograph taken outside the chateau which served as the Australian Corps Headquarters, Ham-sur-Heure, Belgium, 25 February 1919 (source: Flickr Commons/Australian War Memorial E04351)

During the war the most famous poet was Rupert Brooke, who had been a recognised author before hostilities began and whose reputation grew despite (or perhaps because of) his early death. Following Brooke’s death in 1915, his five sonnets collected as 1914 included this one:

III. The dead (Rupert Brooke)

Blow out, you bugles, over the rich Dead!

There’s none of these so lonely and poor of old,

But, dying, has made us rarer gifts than gold.

These laid the world away; poured out the red

Sweet wine of youth; gave up the years to be

Of work and joy, and that unhoped serene,

That men call age; and those who would have been

Their sons, they gave, their immortality.Blow, bugles, blow! They brought us, for our dearth,

Holiness, lacked so long, and Love, and Pain.

Honour has come back, as a king, to earth,

And paid his subjects with a royal wage;

And Nobleness walks in our ways again;

And we have come into our heritage.

During the war, poetry changed from an initial emphasis on patriotism as in the poem above to later expressions of grief and the revulsion many soldiers and others felt with the mounting death toll and battlefield stalemate. Even the poet of imperialism, Rudyard Kipling, wrote this after his son was killed at the age of 18 at Loos in 1915. (John Kipling was last seen stumbling through the mud, screaming in agony after a shell had ripped his face apart. Remains which may have been his were not found until 1992.)

The children (Rudyard Kipling)

These were our children who died for our lands: they were dear in our sight.

We have only the memory left of their hometreasured sayings and laughter.

The price of our loss shall be paid to our hands, not another’s hereafter.

Neither the Alien nor Priest shall decide on it. That is our right.

But who shall return us the children ?…

That flesh we had nursed from the first in all cleanness was given

To corruption unveiled and assailed by the malice of Heaven –

By the heart-shaking jests of Decay where it lolled on the wires

To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes – to be cindered by fires –

To be senselessly tossed and retossed in stale mutilation

From crater to crater. For this we shall take expiation.

But who shall return us our children ?

A new language emerged, exemplified by the then new expression ‘No Man’s Land’ for the ground between the German and French-British front-line trenches. Battle after battle resulted in hundreds of thousands dead and many more wounded while armies advanced only metres at most.

Poetry at the outbreak of war, August 1914

To appreciate World War I we need to remember that there is a great divide between our world and that of 1914. More than all the years that have passed, there are the differences in how people considered the nature of war itself, including the meaning of the words inevitably associated with it, ‘duty’, ‘honour’, ‘manliness’, and the phrase ‘what we are fighting for’.

Today we see war through television, film and photographic images of devastated cities, of survivors weeping over the bodies of their dead, due to the immediacy of television news reporting of today’s conflicts, the frequent documentary films recording World War II battles and their aftermath across Asia, Europe and the Middle East and even the few flickering images of soldiers ‘jumping the bags’ or ‘going over the top’ into the morass of muddy Flanders’ fields in the Great War. In the war of a century ago there was very little of that projected more-or-less reality to compare with the rhetoric peddled by governments, schoolmasters and clergymen.

Most people in Europe had not known war since 1871. Subjects of the British Empire had only the limited experience of distant colonial conflicts like the Boer War or the earlier fighting in Sudan, Zululand, the Crimea and New Zealand. Americans had distant memories of their Civil War. But British Empire boys were still schooled for war by the rousing poems of wars past.

From the Crimean War emerged Lord Tennyson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade: ‘Theirs not to reason why/Theirs but to do and die’. The French General Pierre Bosquet, witnessing the Charge, remarked, ‘C’est magnifique, mais n’est pas la guerre’ – ‘it is magnificent but it is not war’, a comment that could equally have been made about Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg in 1863 or Antill’s Charge at The Nek in 1915. It could fairly be suggested that Bosquet, in making such a remark, was overcome by un excès de politesse.

Empire schoolboys also learned that war was like a game; poetry helped teach the lesson. ‘Much of the literature at school and for teenage reading in the Victorian and Edwardian period’, according to Stephen Wade, ‘had been concerned with stressing the male codes of heroism in war.’ (1) For example, from the First Sudan War of 1885 came Sir Henry Newbolt’s poem, Vitaï lampada, meaning roughly ‘passing the torch’.

Vitaï lampada(Henry Newbolt)

The sand of the desert is sodden red,

Red with the wreck of a square that broke;

The Gatling’s jammed and the colonel dead,

And the regiment blind with dust and smoke.

The river of death has brimmed his banks,

And England’s far, and Honour a name,

But the voice of schoolboy rallies the ranks,

“Play up! play up! and play the game!”This is the word that year by year

While in her place the School is set

Every one of her sons must hear,

And none that hears it dare forget.

This they all with a joyful mind

Bear through life like a torch in flame,

And falling fling to the host behind

“Play up! play up! and play the game!”

Newbolt’s torch is a persistent image (see Appendix 1 to this article).

When war broke out in August 1914, young men of the warring nations rushed to enlist. In England the patriotic fervour was personified by Rupert Brooke.

The soldier (Rupert Brooke)

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Serving with the Royal Naval Division, Rupert Brooke survived the Antwerp fighting in October 1914. He died, unheroically, of an infected mosquito bite while on his way with the British Army to Gallipoli in April 1915. By his death, Brooke gained immediate international celebrity and homage, such as that paid in Joyce Kilmer’s article, ‘A genius whom the war made and killed’, in the New York Times of 12 September 1915. ‘And he who had been a curious student of modern fallacies’, Kilmer wrote, ‘was quick to acknowledge the cleansing might of war and to do homage to the immortal virtues which peaceful England had for a time forgotten.’ (Kilmer himself was a poet of sorts, whose most notable work commenced, ‘I think that I shall never see/A poem lovely as a tree’.)

Many women were fervent war supporters, too, including some of a literary bent. In August 1914, Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, supported by then popular female writers such as Mrs Humphry (Mary) Ward and Baroness Orczy, founded the Order of the White Feather, to shame young men into enlisting. The Daily Mail of 31 August 1914 carried the story ‘Women’s war: white feathers for slackers’ and Fitzgerald warned young men that the humiliation of being whacked with a white feather by a young woman was more terrible than anything likely to be experienced in battle. (2)

It is not recorded whether poetry played any part in this form of patriotic fervour, although Orczy, full name Baroness Emma Magdolna Rozália Mária Jozefa Borbála ‘Emmuska’ Orczy de Orczi, born in Hungary but residing in the Home Counties, was the author of the Scarlet Pimpernel novels and at least had a nodding acquaintance with prose.

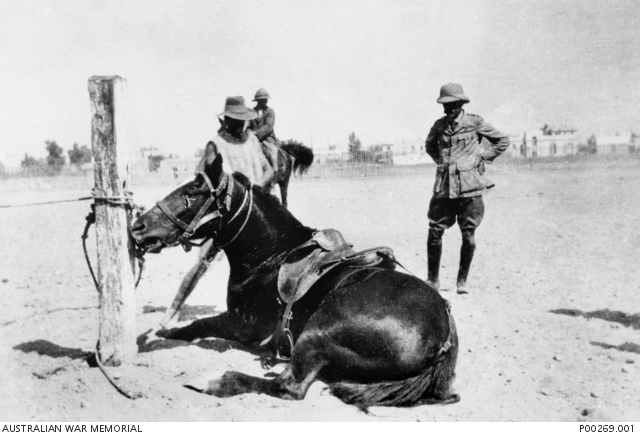

Australian poet at war: Egypt. Captain Andrew Barton ‘Banjo’ Paterson (right) of 2nd Remounts, Australian Imperial Force, inspects a sulking horse (Flickr Commons/source: Australian War Memorial P00269.001)

The nature of the war changed the nature of its poetry

Of course, all of this early poetry was written before the industrial-scale slaughter of the Verdun and Somme battlefields of 1916 and all of the other battles which followed before the guns eventually fell silent at 11am on 11 November 1918, by which hour the ‘butcher’s bill’ stood at almost ten million soldiers’ lives. Civilian deaths, due to war-related famine and diseases, were almost six million, not including those due to the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918-19.

To those who lived through it, it was ‘The Great War’. After the Armistice it became ‘The war to end all wars’, a rebadging to give meaning to what many of the survivors and the grieving had come to see as a meaningless waste of life. The wording on ‘The King’s penny‘, ‘He died for Freedom and Honour’, was another way of trying to convince the families of the dead that it had all been worth it, after all.

Then, of course, wars reappear in different ways for later generations, as one of the lesser-known Great War poets noted when imagining a meeting of community and business leaders considering how best to memorialise the dead.

The next war (Osbert Sitwell)

The long war had ended.

Its miseries had grown faded.

Deaf men became difficult to talk to,

Heroes became bores.

Those alchemists

Who had converted blood into gold

Had grown elderly.

But they held a meeting,

Saying,

“We think perhaps we ought

To put up tombs

Or erect altars

To those brave lads

Who were so willingly burnt,

Or blinded,

Or maimed.

Who lost all likeness to a living thing,

Or were blown to bleeding patches of flesh

For our sakes.

It would look well.

Or we might even educate the children.”

But the richest of these wizards

Coughed gently;And he said:

“I have always been to the front

In private enterprise,

I yield in public spirit

To no man.

I think yours is a very good idea,

A capital idea,

And not too costly . . .

But it seems to me

That the cause for which we fought

Is again endangered.

What more fitting memorial for the fallen

Than that their children

Should fall for the same cause?”Rushing eagerly into the street,

The kindly old gentlemen cried

To the young:

“Will you sacrifice

Through your lethargy

What your fathers died to gain?

The world must be made safe for the young!”

And the children

Went . . .

Moving on

In his book, Farewell, Dear People, chronicling ten of Australia’s Great War ‘lost generation’, Ross McMullin quotes Helen McCrae, sister of the 60th Battalion’s commander, Geoff McCrae, killed in the disastrous Fromelles battle of 1916: ‘Twenty-one years since Geoff was killed… all for nothing, but thank goodness he does not know that’. (3) The Great War had been the most destructive war in human history; it retained that title for just two decades.

There follow three Appendices: Appendix 1: Passing the torch; Appendix 2: Who were the war poets? Appendix 3: Online resources on war literature.

Appendix 1: Passing the torch

David Stephens

Sir Henry Newbolt came to dislike his poem Vitaï lampada but others have kept the flame alive. Canadian John McCrae’s famous poem In Flanders Fields (1919) includes the lines ‘To you from failing hands we throw/The torch; be yours to hold it high’.

This has featured for a number of years on the official Anzac Day commemoration site for Queensland. It was written by Colonel Arthur Burke OAM, who was partly inspired by essays written by schoolgirls:

On 25 April 1915 a new world was born. A new side of man’s character was revealed. The Spirit of ANZAC was kindled. It flared with a previously unknown, almost superhuman strength. There was a determination, a zest, a drive which swept up from the beaches on Gallipoli Peninsula as the ANZACs thrust forward with their torch of freedom. As they fell, they threw those following the torch so their quest would maintain its momentum. That Torch of Freedom has continually been thrown from falling hands, has kindled in the catchers’ souls a zeal and desire for both our individual liberty and our countries’ liberty. That desire has been handed down with the memory and burns as brightly as the flame which first kindled it.

The Governor of Tasmania, Peter Underwood, commented on Colonel Burke’s vision here.

In 2002, a Tasmanian entrant in the Simpson Prize, a government-sponsored essay competition for secondary students, quoted Colonel Burke’s words and went on to say:

From the first moment of the ANZAC Gallipoli experience, to this very day many average and outstanding Australians alike have taken up the challenge, caught the torch, held it bright and high, and in the hope of emulating the immense courage, stamina, heart, devotion, sacrifice, bravery, determination and mateship that the Diggers once displayed at Gallipoli, have embraced the Anzac spirit and expanded, developed and confirmed the values it beholds throughout their life. This in turn has resulted in countless contributions in wartime and in peace, of little to great significance to our local communities, our nation as a whole and to other nations around us.

Meanwhile, in 2001, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs, Alexander Downer, had said this at the Lone Pine ceremony at Gallipoli:

Here was kindled the torch of the Anzac spirit. It has been proudly passed to Australia’s sons and daughters, to those who have struggled and died on fields far from home. Its light was renewed at El Alamein and on the Kokoda Track, at Kapyong and Long Tan.

On Anzac Day, 2010, Prime Minister Rudd took up the torch.

So what is this legend that we call ANZAC? How has it shaped our nation’s life? How does it offer quiet counsel and gentle direction as we seek to chart our future? And how do we best nurture its flame for another century as we approach the first centenary of the ANZAC landings? I believe each generation of Australians has a duty to pass this torch to the next… So how then do we keep this flame alight for the century to come?

The then prime minister went on to announce the Fraser-Hawke commission to look at how Australia should commemorate the Anzac centenary. Accordingly, in 2013, these words appear on the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board website, over the name of its Chair, Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston (Ret’d):

The Board is determined to ensure that the Anzac Centenary is marked in a way that captures the spirit and reverence it so deserves and that the baton of remembrance is passed on to this and future generations.

The bolding is in the original. Newbolt’s torch is sometimes a baton but the sense is the same.

Appendix 2: Who were ‘The War Poets’?

War poets (act. 1914-1918) is a convenient, though somewhat diffuse, term referring primarily to the soldier-poets who fought in the First World War, of whom many died in combat. The best-known are Richard Aldington, Edmund Blunden, Rupert Brooke, Robert Graves, Julian Grenfell, Ivor Gurney, David Jones, Robert Nichols, Wilfred Owen, Herbert Read, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon, Charles Hamilton Sorley, and Edward Thomas.

Most of these writers came from middle-class backgrounds; many had been to public schools and served as officers at the front. In fact, hundreds of ‘war poets’ wrote and published their verse between 1914 and 1918, often capturing the initial mood of excitement and enthusiasm, although only a handful – largely those who wrote in protest – are read and admired today, with Wilfred Owen achieving an iconic status within British literature and culture.

Other war poets whose work appeared between 1914 and 1918 were not involved in fighting. The Times supplement, War Poems, August, 1914–15, for example, included contributions from established civilian poets such as Robert Bridges, Rudyard Kipling, Laurence Binyon, and Thomas Hardy. Catherine Reilly’s 1978 bibliography of English poetry of the First World War lists over 3000 works by 2225 poets. More than half of this war poetry was written by male civilian writers and a quarter by women. A recent interest in the work of such women poets as Vera Brittain, Margaret Postgate Cole, Rose Macaulay, and Charlotte Mew has also significantly extended understanding of war poetry of the period.

Santanu Das, ‘War poets‘, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Appendix 3: Online resources on war literature

1. Oxford University

One of the best ways to visit the War Poets is Oxford University’s ‘World War One poetry digital archive‘. In its own words:

The First World War Poetry Digital Archive is an online repository of over 7000 items of text, images, audio, and video for teaching, learning, and research.

The heart of the archive consists of collections of highly valued primary material from major poets of the period, including Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg, Robert Graves, Vera Brittain, and Edward Thomas. This is supplemented by a comprehensive range of multimedia artefacts from the Imperial War Museum, a separate archive of over 6,500 items contributed by the general public, and a set of specially developed educational resources. These educational resources include an exciting new exhibition in the three-dimensional virtual world Second Life.

Freely available to the public as well as the educational community, the First World War Poetry Digital Archive is a significant resource for studying the First World War and the literature it inspired.

This site features the works of Edmund Blunden, Vera Brittain, Robert Graves, Ivor Gurney, David Jones, Roland Leighton, Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon and Edward Thomas.

2. The War Poets Association

Another excellent site is that of the War Poets Association which covers poetry from the many conflicts of the twentieth century.

The War Poets Association aims to promote interest in the work, life and historical context of poets whose subject is the experience of war. It is interested in war poets of all periods and nationalities, with a primary focus on conflicts since 1914: mainly the First World War, The Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, and Ireland.

There are several societies dedicated to individual war poets; the WPA aims to work with these to promote their activities and to provide an opportunity for them to join in events of general interest.

This website aims to be one of the primary resources on the Internet for research into and discussion of Twentieth Century international war poetry, and to provide a selection of useful links. If you would like to recommend links or help build the resource, please contact the editor at editor@warpoets.org.

The Association’s collection includes the works of those poets who celebrated what they saw as the good in and of war, the worth for young men in sacrificing their lives in battle, the notion of ‘duty’ and the like. The Association also includes the work of the war poets featured in the Oxford University site.

3. BBC

The BBC has extensive coverage of poetry, prose, art and music of World War I. Among other material there are radio programs on British painters and on writers of the Somme, a TV documentary about war poetry, and programs on ballads and music of the war years – and this is just 2013.

4. No Glory in War

This relatively new site, set up by members of Britain’s arts community and others, has poetry and related material, including Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy reading her poetry and items on Kipling, Owen, Sassoon and their work. There is also a poem about a cat who was shot for treason.

Notes

(1) Stephen Wade, The War Poets 1914-18, Studymates, np, 2003, p. 19

(2) Nicolletta F. Gullace, ‘White feathers and wounded men: female patriotism and the memory of the Great War’, Journal of British Studies, 36, 2, April 1997, p.178; Paul Ham, 1914: The Year the World Ended, Heinemann, Sydney, 2013, p. 585.

(3) Ross McMullin, Farewell, Dear People: Biographies of Australia’s Lost Generation, Scribe, Brunswick, Vic., 2012, pp. 90-91

Bibliography available on request admin@honesthistory.net.au

2 November 2013

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.