‘Singing country: the musical legacy of David Morrison, Australian of the Year – and a straw in the wind at the Australian War Memorial?’, Honest History, 2 February 2016

Before David Morrison became Australian of the Year he was a Lieutenant-General and Chief of Army, one of the top brass in the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Not long before he retired from that job, he decided to enter, in a modest way, the musical entrepreneur business, and the result is well worth writing about for what it says and hints at. The Australian War Memorial and its director Brendan Nelson also played a notable role in this story.

‘On every Anzac Day’ by John Schumann

Browsing the Memorial’s website early in the New Year, Honest History noticed the Memorial’s ‘Year in Review, 2015’ video, 6 minutes and 27 seconds long. It’s now gone from the front page of the website down a level to the ‘Centenary’ page but it’s also on You Tube and on the Memorial’s Facebook page.[1] We have written briefly about the video elsewhere; this story is about the video soundtrack, John Schumann’s song ‘On every Anzac Day’ (official video). The words of the song are printed at the end of this article.

Schumann’s song tells its story through the eyes of a white soldier who recalls an Indigenous comrade (‘When the bullets are whining past your head, you’re all just shades of grey’). What caught our attention particularly, though, were these few lines:

I asked him once why he volunteered for that hellhole far away

To fight for someone else’s king and the land they took away

He said “One invading mob’s too many” and then he walked away

and then, right at the end,

We remember those first Australians, who joined and fought and died …

We remember the fighting First Australians – now – and on every Anzac Day.

The song has the strong theme of shared fear in combat and, afterwards, shared scars and terrors and rejection of the black soldier by the RSL. The names of battles throughout the song make it clear that it is not just about World War I during the centenary of Anzac but about all our wars. But it also mentions invasions and dispossessions and that is what this article is about.

How the song was written

Honest History interviewed General Morrison just a week before he became Australian of the Year and we asked him how the song came to be written. He said the song wasn’t meant to start a social crusade but he was clear from reading books like Joan Beaumont’s excellent Broken Nation that it was important to tell the full story of our wars. He believed stories of war ‘are wired into our DNA’ – more of that later – but one area where we were ‘underdone’ was recognition of Indigenous service.

We don’t fully recognise the amazing stories of Indigenous men and women’s involvement in World War I and all our wars. I thought about the best way to make a contribution and that seemed to be through a song.

General Morrison had spent Anzac Day 2014 at Thursday Island where his speech recognised ‘that some Australians remember men from across the world coming here to take their land’. He knew John Schumann for his song-writing and his work with Vietnam Veterans and he approached Schumann to write a song that recognised Indigenous service in uniform. Necessarily, the story had to be told from a ‘white fella’s’ perspective – because Schumann was white – but it had to tell about Indigenous experience. Morrison worked closely with Schumann on the song though there was no editorial control. ‘I was happy with all the lyrics’, Morrison recalled.

General Morrison had spent Anzac Day 2014 at Thursday Island where his speech recognised ‘that some Australians remember men from across the world coming here to take their land’. He knew John Schumann for his song-writing and his work with Vietnam Veterans and he approached Schumann to write a song that recognised Indigenous service in uniform. Necessarily, the story had to be told from a ‘white fella’s’ perspective – because Schumann was white – but it had to tell about Indigenous experience. Morrison worked closely with Schumann on the song though there was no editorial control. ‘I was happy with all the lyrics’, Morrison recalled.

When Honest History spoke to John Schumann he remembered that General Morrison had said he wanted the new song to be bigger than Schumann’s earlier hit from 1983, ‘I was only 19’. (A review of the children’s book version.) Schumann said writing the song had been quite a challenge for him, having to find a narrative point, to deliver for Morrison but make the composition work as a song. Schumann worked on the song full-time for ten days. He had some historical research done but found there was a difference between history books and the tune and lyrics of a song.

Schumann came up with the idea of a white fella serving beside a ‘black fella’ who made comparisons between the white invasion of Australia and possible future invasions of Australia by other powers. So Schumann settled on ‘one invasion too many’ as a narrative point. It was, he said, ‘a dangerous thing to do’ in song-writing terms but it worked.

Does the song equate invasion then with potential invasion later?

We discussed with David Morrison whether the words in the song ‘One invading mob’s too many’ were indeed an attempt to equate white settler invasion with more recent threatened invasions. General Morrison recognised that some Indigenous people might equate fighting in uniform to defend Australia against, say, Germans or Japanese, with Indigenous warriors fighting to defend their country against settlers in 1788 and after. But he said he himself was not trying to equate the two.

The Queen’s uniform

We asked David Morrison whether there was a reluctance in the Australian Defence Force to recognise Indigenous fighting in the Frontier Wars because of ADF diffidence at recognising those who fight against the Queen’s (King’s) uniform. General Morrison said he did not see this as a big issue. He said that, since World War II, many of our immigrants had come from countries we previously fought against; Australians had shown a great capacity to move on from conflict and to accommodate former enemies. In any case, in the Frontier Wars much of the fighting on the settler side was done by civilians, not by men in uniform.

(Radio Australia/Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet)

(Radio Australia/Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet)

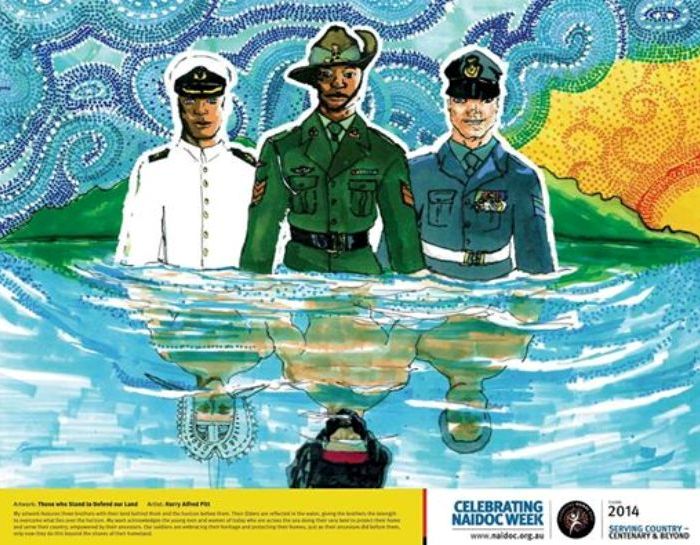

Honest History asked General Morrison if he recalled the NAIDOC Week 2014 poster entitled ‘Those who stand to defend our land’, which showed Indigenous service people in uniform and, reflected in a pond below them, Indigenous warriors. He recalled the poster and noted that the ADF’s recruitment of Indigenous men and women has referred to Indigenous warrior traditions. (The Australian Army now has an ‘honouring warrior spirits’ ceremony but the ‘high profile’ recruitment material on the ‘Army Indigenous community’ part of the Army website seems not to take the tradition back further than the Boer War.) On the other hand, commenting on the Frontier Wars, he said, ‘we’ve tended to write them [Indigenous warriors] out of our history’ compared with New Zealand, where there is more coverage of the Maori Wars.

Can we have recognition of both Indigenous service in uniform and Indigenous service not in uniform?

Honest History then asked David Morrison whether recognition of Indigenous service and encouragement of Indigenous recruitment to the ADF will swamp the possibility of greater recognition of Indigenous warriors in the Frontier Wars. Our question asked, essentially, whether recognition of Indigenous service in uniform precluded recognition of Indigenous service not in uniform.

General Morrison said he was not qualified to give an opinion on this question; his focus as Chief of Army had been on Indigenous service and recruitment. The Schumann song had helped recruitment of Indigenous people to the ADF, as the improved numbers have shown. Honest History agreed with Morrison that there is a range of views among Indigenous Australians about whether and how to give more recognition to Indigenous warriors in the Frontier Wars.

Shane Mortimer’s view

Shane Mortimer is a Guumaal Nation Ngambri Allodial Elder. He noted the lyrics ‘the land they took away’ in Schumann’s song and he pointed out that ‘allodial title cannot be extinguished, hence the land has never been taken away from First Nations (allodial) People’. He went on:

The lyrics of “On every Anzac Day” acknowledge the invasion of Australia since 1788 with “one invading mob’s too many” and these words have been endorsed by the then Chief of Army and the Director of the Australian War Memorial [see below]. The next step should be to officially acknowledge service by Allodial People, who, without uniform, still defend their country.

Noah Riseman’s view

Noah Riseman is an Associate Professor in History at the Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, and a Chief Investigator in the Serving Our Country project at the Australian National University.[2] This four-year project is researching the history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service in Australian defence and auxiliary services from the 1890s to the present.

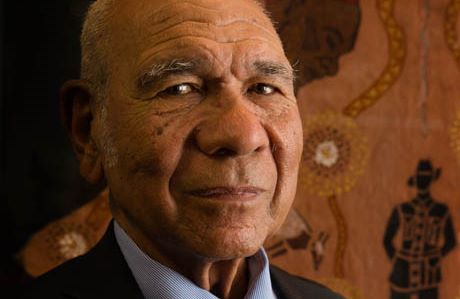

Uncle Roy Mundine, inaugural Indigenous Elder, Australian Army (Australian Army)

Uncle Roy Mundine, inaugural Indigenous Elder, Australian Army (Australian Army)

During his research, Riseman has worked closely with Indigenous servicemen and women and their families, although he is not himself Indigenous. (Honest History tried to get comment from Indigenous members of the Serving Our Country project but they were unavailable.) Serving Our Country does not focus directly on dispossession and resistance, though it recognises this aspect of Australian history. Riseman said a number of his interviewees have mentioned the history of Indigenous dispossession.

Riseman has seen evidence in his research that Indigenous service people see their participation in the Australian military as part of a longer tradition of Indigenous people fighting for their country. He felt that the Schumann song has a similar significance to Serving Our Country.

The song is like the project [he said]: it’s another way of bringing this question back up but through a different lens. Once you recognise Indigenous service in our defence forces, the next logical question is “how about recognising what Indigenous people did in resisting dispossession?”

The Anzac legend and Anzackery

Broadening our conversation with David Morrison, we asked him about his views on the role of Anzac today, given his ambivalent remarks about it in some of his speeches. For example, at a White Ribbon breakfast in Adelaide in November 2014, he talked about the ‘totems’ and stories that contribute to male bonding in the ADF, bonding which is ‘exclusive, not inclusive’.

They [the stories] reinforce a view of “us and them”. In hyper masculine environments, like armies, “them” is defined by being weaker physically, not drinking “like a man”, not bragging of sexual conquest, being more introverted or intellectual, and of course being female.

I think that such distortion is a strong element in one of our great foundation narratives, not just for the Army but for Australia. I am talking about Anzac. The Anzac legend – as admirable as it is – has become something of a double-edged sword …

Where do women, or Indigenous soldiers fit in that narrative? They don’t and so, over time, such stories become myths and then myths become legends and then they become some unalterable truth.

General Morrison went on to discuss misogyny and domestic violence in Australian culture generally and the pressures on men to conform to a ‘distorted masculine image’. The Adelaide speech deserves a close read. Our talk with him, though, focused on the Anzac legend and commemoration.

There is almost no country on earth that remembers its military service the way we do [Morrison told Honest History]. Australians have an overwhelmingly positive view of military service, particularly the qualities like mateship and professionalism that it demonstrates. Our military is an overwhelming force for good. On the other hand, if we have a utopian view of military service – if we look through rose-tinted glasses – we do everyone a disservice. We need to tell true stories.

General Morrison addresses Dawn Service, Canberra, 25 April 2015 (Department of Defence)

General Morrison addresses Dawn Service, Canberra, 25 April 2015 (Department of Defence)

General Morrison said he admired Joan Beaumont’s book, Broken Nation, and James Brown’s Anzac’s Long Shadow for this reason. He agreed that we needed to avoid the overblown version of remembrance that had been characterised as ‘Anzackery’. We said Honest History tried to distinguish between Anzackery and a respectful version of Anzac. We consciously used the motto ‘not only Anzac but also (many other strands of our Australian history)’ to indicate that, of course, war is important (because of what it has done to Australia and Australians) but so are many other parts of our history.

Morrison mentioned his speech to the Anzac Day Dawn Service in 2015 as a summary of his views in this area. While the speech includes a list of battles and refers to military sacrifice it is notable also for its recognition of the impact of war and for its historical perspective.

The long journey from Gallipoli to the breaking of the German line in November 1918, marked by failure and success, loss and life long mateship had left its indelible mark on them and their country. If war is a sin against humanity, as some would hold, then war itself is punishment for that sin, compounded by its endless repetition and its hold on those who have experienced its terrors. Such was the mark many brought home to their families who continued, as so many families have and still do, to live daily with the indelible memories of those who had fought and who cannot let go.

Morrison then referred to the ‘line’ that connects us to Australians of a century ago.

It is a line made more whole by our recognition of the first people of this land and our sorrow for their treatment. It is a line given colour and vibrancy by our cultural richness and diversity, drawn as it is from migrants from all corners of our world. It is a line rooted in our freedom of expression and of belief, and the affirmation of our democratic nation state.

In his Adelaide and Dawn Service remarks, General Morrison foreshadowed most of the themes of his Australian of the Year speech. Finally, in our interview with him, he commended the work Director Nelson and his staff at the War Memorial had done in broadening the coverage of war, for example, in the final room of the refurbished World War I galleries, which looked at the aftermath of the war. We said we had written extensively on the Honest History site about aspects of the Memorial’s work; we had said consistently that the Memorial was the best in the world at what it did but that it needed to broaden its perspective to look more comprehensively at all aspects of war, including what Schumann refers to in the song as ‘the scars/Of the tears and fears and terrors that still tracked us down the years’.

The role of the War Memorial in ‘On every Anzac Day’

John Schumann said the War Memorial had been very helpful in the production of his song and its later incorporation in the Memorial’s ‘Year in Review’ video. The separate ‘official video’ accompanying the song acknowledges the ‘enthusiastic support’ of Director Nelson and his staff in facilitating access to materials at the Memorial and in other aspects.

General Morrison, John Schumann, Director Nelson, song launch, April 2015 (Department of Defence)

General Morrison, John Schumann, Director Nelson, song launch, April 2015 (Department of Defence)

When the song was launched at the Memorial in April 2015 Director Nelson acknowledged the ill treatment Indigenous servicemen received when they returned home to an unequal society. He added: ‘The music and words [of the song] will burrow deep into our collective consciousness’. The song was sung at the opening of the Captain Reg Saunders Gallery at the Memorial on Remembrance Day 2015 in the presence of Director Nelson and the then Chairman of the Memorial’s Council, Admiral Doolan. (Reg Saunders is said to have been the first Indigenous officer in the Australian Army.) Finally, Director Nelson’s staff put together the ‘Year in Review’ video, including the song as soundtrack.

The Memorial’s enthusiastic support for a song that acknowledges not just Indigenous uniformed service but also Indigenous dispossession contrasts with the Memorial’s current official attitude to the Frontier Wars. A note on the Memorial’s website argues that the Memorial’s Act precludes it recognising ‘internal conflicts between the Indigenous populations and the colonial powers of the day’. Elsewhere on the site the number of deaths in those conflicts is put at 2500 settlers and ‘about 20,000’ Indigenous Australians although recent research suggests the number of Indigenous deaths could be somewhere between 65 000 and 100 000. (The Memorial’s note twice uses the spelling ‘Aboriginies’, which suggests the note needs revision.) Then, when you wander down to the furthest corner of the Memorial’s basement you find a caption saying that British regiments in Australia between 1801 and 1870 ‘suppressed Aboriginal resistance to white settlement’. That’s all.

The Memorial through Director Nelson has often made clear that it believes it is not the place to commemorate the Frontier Wars. Yet the Director has clearly recognised the fact of dispossession and trauma.

It is certainly my view and I certainly don’t say this with anything but immense respect for Indigenous peoples, and a sense none of us will ever be able to understand what they went through when that first fleet arrived and everything that came afterwards and to some extent still happens today.

Now in 2015 and 2016 the Memorial has endorsed and used a song which seems to equate Indigenous Australian resistance to that dispossession with Australian resistance to hostile aggression in the twentieth century.

There is a saying that changing received policy is like changing the direction of an ocean liner. The Australian War Memorial looks a little like such a vessel, afloat on the lawns at the top of Anzac Parade. Does ‘On every Anzac Day’ mark a course correction, however slight?

Conclusion

David Morrison wants to use his Australian of the Year tenure to speak out on diversity, equality, an Australian republic and the protection of families from domestic violence – and the welfare of veterans. He hopes to be a voice for inclusion and understanding. While he was a soldier for 36 years his becoming Australian of the Year should not be seen as a gesture towards khaki-clad jingoism in the time of the centenary. (There have been enough of those gestures recently.) General Morrison’s emphasis on inclusion is evident also in the role he played in working with John Schumann to develop the song ‘On every Anzac Day’ and then with Director Nelson and the War Memorial to promote the song.

Schumann’s song is apparently having a positive impact on Indigenous recruitment to the ADF, partly by appealing to Indigenous warrior tradition. In association with this, past Indigenous uniformed service is gaining overdue and deserved recognition. It remains to be seen whether the official endorsement of the song – including its words about invasion and dispossession – by the ADF and the War Memorial will help move Australia towards recognition of Indigenous non-uniformed service to country in 1788 and afterwards. It is a moot point whether stressing past, present and future Indigenous service in uniform precludes or delays recognition of non-uniformed service.

Gargoyle of Indigenous Australian, Australian War Memorial, alongside flora and fauna (The Conversation/Lisa Barritt Eyles)

Gargoyle of Indigenous Australian, Australian War Memorial, alongside flora and fauna (The Conversation/Lisa Barritt Eyles)

Whether, how, where and to what extent Australia recognises non-uniformed Indigenous service in defence of country is ultimately up to men and women of Arrente, Gadigal, Ngambri, Ngunnawal, Noongar, Walpiri, Wiradjuri, Wurundjeri, and other Indigenous heritage, not to white fellas. But white fellas have to cooperate and that is why we should note and recognise the actions of General Morrison and Director Nelson in blessing and supporting a song that includes the words ‘One invading mob’s too many’ and hints that ‘fighting First Australians’ have not always worn the Queen’s uniform.

David Stephens is Secretary and Editor of Honest History.

John Schumann is donating the royalties from ‘On every Anzac Day’ to Trojan’s Trek, a wilderness-based program for veterans suffering from PTSD.

Appendix: On every Anzac Day (lyrics by John Schumann)

Ghosts and memories are loitering still in the corridors of time

There’s sorrow, smoke and stories in the barracks of my mind

I’m with him still in the trenches, I can see his dark, brown eyes

And his courage gave me courage when I was sure we were going to die

I asked him once why he volunteered for that hellhole far away

To fight for someone else’s king and the land they took away

He said “One invading mob’s too many” and then he walked away

And I lost him in the crowds waving flags on the side of the road — like every Anzac Day

From Murray Bridge and Mundrabilla, from Naracoote and Perth

First Australian station hands, shearers, gangers, clerks…

And there was no black, there was no white, just a dirty khaki brown

And on our upturned slouch hat brims, we all wore the “Rising Sun”

Soldiers, brothers, all Australians, we had no time for race

When the bullets are whining past your head, you’re all just shades of grey

He kept his medals in their box in a drawer — he tucked them well away

But he’d pull them out and put them on and put them back again — on every Anzac Day

Armentieres and Flanders, Tarin Kowt and Salamau-Lae

Amiens and Morotai, Long Tan, Dispersal Bay

Somalia, Crete and Kapyong, Iraq and the Solomons

Paschendaele, Maprik and Tarakan — they were there — the first Australians

And when the show was over and we made it back to Australia’s shores

From Pozieres and Herleville Wood, Benghazi and Fremicourt

We drifted back into our lives, and we all tried to hide the scars

Of the tears and fears and terrors that still tracked us down the years

He tried to join the RSL but the bastards wouldn’t let him in

They didn’t see a soldier, just a first Australian

And I wonder what it was that we fought for and what it was we gave away

There’s reconciliation still to come — on every Anzac Day

So when the sun sets in the evening, when the dawn lights up the sky

We remember those first Australians, who joined and fought and died

From the missions, bush and station country, towns and Torres Straits

We remember the fighting First Australians — now — and on every Anzac Day

The Wills tragedy, 1861: watercolour by TG Moyle (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of Queensland). The murder of 18 white settlers, described by CE Sayers in 1967 as ‘the worst massacre of white men in the history of Australian pioneer settlement’, led in turn to the Cullin-la-ringo massacre of an unknown number of Indigenous Australians.

The Wills tragedy, 1861: watercolour by TG Moyle (Wikimedia Commons/State Library of Queensland). The murder of 18 white settlers, described by CE Sayers in 1967 as ‘the worst massacre of white men in the history of Australian pioneer settlement’, led in turn to the Cullin-la-ringo massacre of an unknown number of Indigenous Australians.

Notes

[1] The video was posted on You Tube on 17 December 2015. By 30 January 2016 it had been viewed just 1540 times. It was posted on the Memorial’s Facebook page on 18 December, where by 30 January it lay beneath dozens of later posts and comments.

[2] Noah Riseman is author of the books In Defence of Country: Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen and Women, Defending Whose Country? Indigenous Soldiers in the Pacific War and co-author of the forthcoming book Defending Country: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Military Service since 1945.