‘What is history? An old question; a new answer?’ Honest History, 1 December 2015

Jim Windeyer* reviews World War One: A History in 100 Stories by Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James. Another review by David Stephens. Jim Windeyer also wrote a conference paper on an early draft of the story of his grandfather, WA Windeyer.

_________________________

It is over ten years since the publication of The Secret River by Kate Grenville. The book and an interview with the author led to a debate in the media on the rival claims of historians and novelists to be accurate portrayers of the past. The historian Inga Clendinnen stated her position in Quarterly Essay (hereafter QE) 23, August 2006.

In some ways the outcry by the historians was unnecessary: Grenville had never suggested that her work was history, despite the very considerable research that had gone into it (QE 23, p. 66). Clendinnen argued that there is a fundamental difference between the historian’s discipline and that of the writers of fiction, even if it was closely researched historical fiction. In her view ‘historians are the permanent spoilsports of imaginative games played with the past’ and it is the historian’s job ‘to unscramble what actually happened from whatever the current myth might be, and to inquire into what myth makers are up to – not to play myth-making too’ (QE 23, pp. 20, 46).

In some ways the outcry by the historians was unnecessary: Grenville had never suggested that her work was history, despite the very considerable research that had gone into it (QE 23, p. 66). Clendinnen argued that there is a fundamental difference between the historian’s discipline and that of the writers of fiction, even if it was closely researched historical fiction. In her view ‘historians are the permanent spoilsports of imaginative games played with the past’ and it is the historian’s job ‘to unscramble what actually happened from whatever the current myth might be, and to inquire into what myth makers are up to – not to play myth-making too’ (QE 23, pp. 20, 46).

The late Geoffrey Bolton, commenting on Clendinnen’s article, said:

If historians can never achieve Ranke’s goal of rediscovering the past as it actually was, we must take pains to avoid demonstrable error. Story tellers are under no such constraint. They can and should use the materials of the past to offer their audiences insights into the human condition, but we must not call them history (QE 24, p. 67).

In a new book, World War One: A History in 100 Stories, this is given a new twist as the authors argue for the legitimacy of ‘imagined history’. The success of Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang demonstrated that with ‘history’ in the title, even ‘True History’, a work of fiction, could win international acclaim. However, there are two significant differences between that work and the new work. Peter Carey is a novelist and his work is described as a novel – historical fiction. World War One: A History in 100 Stories is written by professional historians and purports to be history, indeed honest history.

The book has been beautifully produced for the 100 Stories project of a team of writers and researchers at Monash University. The team is led by Professor Bruce Scates, Professor of History and Australian Studies and Director of the National Centre for Australian Studies at the university. Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James are PhD candidates at the National Centre. Another outcome from the project is an online version of the key points of each story – at present only 50 of the 100.

One of the strong motivations behind the project was the desire to bring some balance to the treatment of the Australian war experience in World War I at the time of the centenary of the Anzac landing: balance to the ‘story of courage and sacrifice, fortitude and endurance, mateship and resolve’, the ‘nation-building narratives’ that would be told time and again during the Anzac centenary (p. viii). Indeed, it does bring some balance. Among the stories are many that are very moving, some that provoke feelings of anger at folly, waste and injustice, all of the stories in their way remarkable.

There are, however, some significant weaknesses in the publication. Those relating to matters such as punctuation, vocabulary and English expression will be dealt with later. The major issue comes from the book’s claim to be ‘a History’.

In the Introduction the authors say:

Conventional histories are bounded by the archives, and the 100 Stories respects that need for a verifiable “truth”. But the writing of history is also a creative endeavour; a matter of perspective and choice. Very occasionally, we have embarked on what might be called an “imagined history” – constructing the diary of a nurse from medical case notes, sketching the scene of a battle or a homecoming, imagining what one of Australia’s first pilgrims might have thought as he prepared for a journey to war graves overseas (p. xi).

Is there a place for ‘imagined history’ in a ‘History? In Scates’ 2013 novel, On Dangerous Ground: A Gallipoli Story, obviously so. However, in a work like 100 Stories, described as ‘painstakingly researched’ and ‘first and foremost … an educational resource’ perhaps it would be better to present the information with a commitment to ‘verifiable truth’ and leave the imagining to the reader.

In some of the stories readers are alerted to the imaginative genre by expressions such as ‘We can imagine …’ but we cannot be sure that there are not statements which we are led to believe but which may be imagined and even false. This writer – he is a grandson – knows of this problem, having seen an early version of the WA Windeyer story (pp. 79-81). In it Windeyer was said to have ‘whispered a prayer’ over each of the graves of Hunter’s Hill men that he found when visiting the war cemeteries in France and Belgium. There was no evidence for this and there was no word such as ‘perhaps’ or ‘presumably’. When this was pointed out that clause was omitted and other changes were made.

In some of the stories readers are alerted to the imaginative genre by expressions such as ‘We can imagine …’ but we cannot be sure that there are not statements which we are led to believe but which may be imagined and even false. This writer – he is a grandson – knows of this problem, having seen an early version of the WA Windeyer story (pp. 79-81). In it Windeyer was said to have ‘whispered a prayer’ over each of the graves of Hunter’s Hill men that he found when visiting the war cemeteries in France and Belgium. There was no evidence for this and there was no word such as ‘perhaps’ or ‘presumably’. When this was pointed out that clause was omitted and other changes were made.

The value as history of a story that is described in the ‘Sources and further reading’ as an ‘imagined narrative’ (Bernard Haines, pp. 46-9) or a ‘semi-fictionalised account’ (Samuel Mellor, pp. 61-4) is clearly limited. So, too, is that of the story where, in its eight paragraphs, ‘perhaps’ occurs seven times, and ‘never know’, ‘no one knows’, ‘no record of’, ‘more than likely’, and ‘probably’ occur once each (William Riley, pp. 226-7).

Many of the stories we are told are ‘based on’ or ‘draw on’ service dossiers, repatriation files, contemporary newspaper accounts, etc. That would be more reassuring were the sources accurately drawn on. Private Agnew’s ‘soft brown eyes’ that may have persuaded Kathleen Skinner to marry him (p. 332) were, according to his service dossier, grey. Sarah Irwin, the mother of George Irwin (pp. 74-7) is said to have begun writing to the Red Cross in 1916 – ‘I have interviewed …’, and to have ‘continued to hope, pray and imagine until the very end of the war’; ‘I have never been able …’ The one reference given for these two quotations is a letter dated 16 March 1917. That is neither 1916 nor ‘the very end of the war’.

The picture of James Arden (pp. 164-8) that builds up to his resolution to leave the Lake Condah Mission Station on 22 February 1917 depends on a distortion of the sequence of sources. It begins with his letter of complaint in June 1912 about the conditions at the station. The next reference, introduced ‘White authorities soon complained…’ is 27 January 1917: ‘soon’? Then follow quotations from three sources, all of them after Arden has left the station. The manager, Galbraith, wrote on 23 February 1917 and he ‘went on’ – on 13 June. Meanwhile, Mrs Galbraith complained on 24 February. Then the text continues, ‘With the manager and his wife threatening resignation [for which no evidence is given], the government decided to take action’ – by letter on 20 February. Grenville says, when writing The Secret River,

[b]y rearranging and reshaping the scenes … I could create a sequence. That wasn’t quite how it was in the documents, but making a sequence out of these events wouldn’t distort what had ‘really happened’ in any significant way. It would turn them into a story (QE 25, p. 73).

She was doing it for a novel not a history.

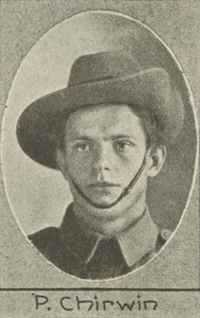

Peter Chirvin (Russian Anzacs/Queenslander)

Peter Chirvin (Russian Anzacs/Queenslander)

Perhaps the dates of these sources have been given incorrectly. Certainly there are instances where that is the case. Peter Chirvin (pp. 19-21) committed suicide in 1919. The date of the source is given as 23 April 1918 – it should be 23 April 1919. The family of Gordon Corbould (pp. 184-5) inserted a notice in the ‘In Memoriam’ column in the Sydney Morning Herald annually on the anniversary of his death, ‘The first on 13 September 1916’. As he was killed in September 1914 it is perhaps not surprising that the first such notice appeared in the Herald in September 1915 not 1916. Charles Campbell (pp. 151-3) and his men, ‘took off for their “first show” at the end of November 1917. Although they were keen to “do something useful in the way of annoying the Hun”, adrenaline and terror sent blood pumping through their chests.’ This sourced from a letter from Charles to his mother dated 8 October 1917.

The expression ‘adrenaline and terror sent blood pumping through their chests’ may have come from the source or may be imagination or exaggeration from the authors. We do not know. The use of extravagant language is another aspect of the work that detracts from its worth as ‘history’. Perhaps Charles, as the product of ‘a leading Sydney boys’ school’, would have had terror and adrenaline pumping blood through his veins or arteries rather than his chest. ‘Killing fields’ are mentioned in several stories although that term is associated with more recent Cambodian history rather than with World War I. The grenade that wounded Vernon Mullin (pp. 100-103) was a ‘ripe explosive’.

As for matters of English grammar etc., the following are among those noticed:

p.104: ‘At the gateway to the Suez Canal [Egypt] held the shipping lines that linked Empire and the dominions’; shipping lanes?

p.140: In August 1915 ‘Bert Crowle, who had been made an officer after a little more than a fortnight, was ordered…’ He enlisted in December 1914. Bert Crowle, little more than a fortnight after being made an officer, was ordered…?

p. 213-4: Emma Rothrmann is spelled thus under the photo but Rothermnn in the text;

p. 228: Hugo Throssells’ hat – or Throssell’s;

p. 249: William Irwin’s citation reads ‘conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’ but when the text goes on it is, ‘“Magnificent gallentry [sic],” to be sure’. And his name is among those on the Australian War Memorial ‘etched forever in bronze’. The names are cast not etched;

p. 308: under the photo the reader is told to ‘Note the church … where the memorial windows to the Rigney Brothers is set’ – are set?

p. 314: the Australians of the 17th Battalion, in their naming of certain sections of the lines after places in Sydney, ‘christened the main sap running into the “Post Broadway”’ – or ‘running into the post, “Broadway”’?

The Luttrell story (pp. 30-31) exemplifies some of these things. The Hobart City Roll of Honour is said to contain the names of three Hanigans, four Hunts and five Luttrells. But, as can be counted on the photo (p. 31), there are four Hanigans, not three. ‘Each day the master craftsman carved another name carefully into the wood’ but with 3500 names, 10-14 years? And are the names carved into the wood or painted on in gold?

Five Luttrells may be correct although there were seven who enlisted in Hobart. However, one died within a month and one did not pass his medical. The text leaves one very confused. It is Emily Luttrell’s story but the letter reproduced and the service dossier drawn on refer to Arthur Parkes who, according to his service record, was wounded five times, not four as stated below the letter. There is no explanation of how Emily Luttrell was the mother of Arthur Leslie Parkes. His next of kin was his wife, Lilian on his dossier, not ‘Lillian’. The approach for the widow’s badge was made by Mrs Myra Bower on behalf of her mother, not by Lilian Parkes herself as is said under the letter (p. 30). And just to complicate things there was an Arthur Luttrell whose next-of-kin was his wife, Ethel Emily.

The Cornelius Danswan story (pp. 94-6) is also confusing. His mother is described as Sarah and his father as Thomas but then it says Thomas married Flora and on the next page it is clear that Flora is Cornelius’ mother.

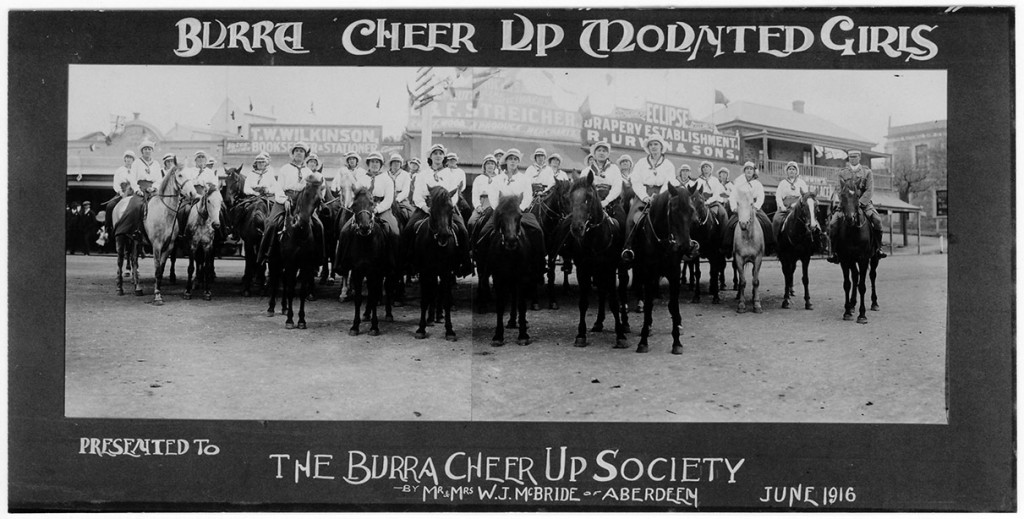

Burra, SA, Cheer Up Mounted Girls, 1916 (Australian War Memorial/DVA Anzac Portal)

Burra, SA, Cheer Up Mounted Girls, 1916 (Australian War Memorial/DVA Anzac Portal)

In many instances in the book the individual story is used as a way into some broader and deeper issues associated with the impact and horrors of the war both at home and overseas, during the hostilities and afterwards. However, the use of the Hutchinson story (pp. 200-201) could be seen as an extension too far. The authors concede:

Here we should sound a word of caution. You can read too much into a single paragraph from a single file, and we can’t assume that our emotional sensibilities today are the same as those in the past, even if that past was barely a hundred years ago. In truth, we know virtually nothing about Hutchinson’s and Carson’s relationship and we can never know what these two men’s sexual preferences may have been.

Yet the story is used as an avenue to discuss homosexuality in the forces. In the introduction the authors say, ‘where possible’, they consulted the families in the stories. Was it possible in this case?

There are also many instances where the authors go on to comment on events or attitudes of the present or recent past. In this way the Hutchinson story leads into a description of the controversy that erupted on Anzac Day 1982 when a group of gay servicemen sought to lay a wreath at the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne.

Of Alfred Morris (pp. 335-6) and his papers it is said ‘Mindful again that he was a witness to history, his accounts of the war on Gallipoli and in the Sinai were deposited in Sydney’s Mitchell Library’. ‘His accounts’ were not mindful of anything; he may have been mindful. However, the Koran that Morris had souvenired and which was among his papers is used as a basis for criticising the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board. The expert panel of historians, of which Professor Scates was the chairman, had recommended to the Board that the Koran be returned to Turkey as a signal of the enduring friendship between Australia and Turkey. As nothing came of the recommendation the story is entitled ‘A Lost Opportunity’. Certainly it would have been a more diplomatic gesture than the reference in the Peter Rados story (pp. 157-9) to Ottoman civilians being victims of ‘genocide’.

In the introduction the Board is portrayed as an obstacle to honest history by its questioning of the inclusion of the Frank Wilkinson story. ‘We [the historians] were presented with an ultimatum: if Canberra was to adopt the 100 Stories project in its commemorative program, Frank Wilkinson’s story would have to go’ (p. viii). The story stayed, as it should have, but one wonders what is usefully achieved by putting the central element of it at the very beginning of the book.

Berrol Mendelsohn (Anzacs online, Mosman Council/Glenn)

Berrol Mendelsohn (Anzacs online, Mosman Council/Glenn)

In the Berrol Mendelsohn story (pp. 279-283) Canberra, this time the government, again comes in for criticism for stalling on the matter of the search for the mass graves at Fromelles. These things seem to be a distraction from the main purpose of the book as do occasional comments such as, ‘The incompetence and cruelty of British command changed all that’, that is, Evelyn Davies’ (pp. 145-8) loyalty and idealisation of ‘all things English’.

In an article in The Age, 11 November 2012, Professor Scates posed the question, ‘What do we owe the generation of men and women who suffered [through] the Great War?’ and answered it, ‘Above all, we owe them the truth’. The 100 Stories have been promoted as ‘above all an educational resource’. It is unfortunate that, given the vast amount of research that went into it, that the worth of this book as a history is diminished by so many faults – some minor, others not so. And, as Clendinnen said, ‘Good history … might even dispel our chronic amnesia regarding war’ (QE 23, p.66).

* Jim Windeyer is a history honours graduate of Sydney and Oxford Universities. He taught history in secondary schools in England and Australia for almost forty years. In 2011 he published a biography of his grandfather: W.A.Windeyer: Not Idle but Useless? Not He!