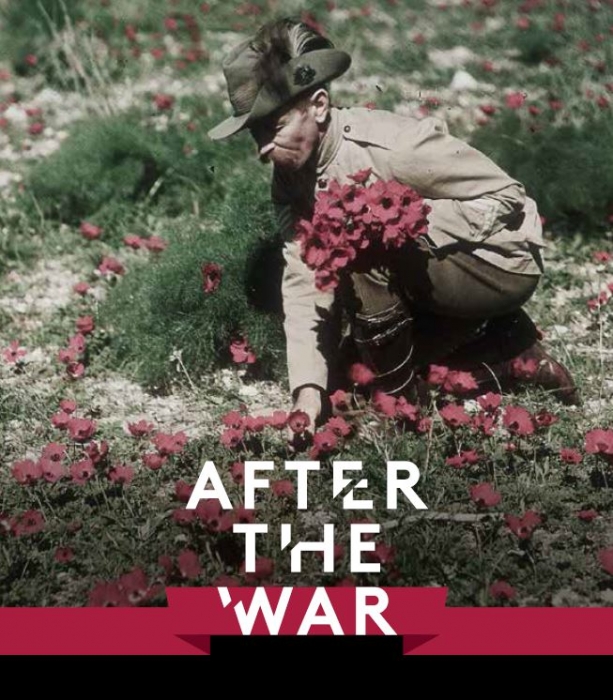

‘Questions downstairs: the After the War exhibition at the Australian War Memorial’, Honest History, 13 December 2018 updated

In 2014, when the refurbished First World War galleries at the Australian War Memorial were about to be opened, the Memorial said the new set-up would give some attention to what Australia was like before the war, as well as the war’s ‘enduring legacy’. As it turned out, before the war got two paragraphs in the new galleries and after got about five per cent of the total floor space devoted to the Great War.

Then, when he was interviewed by Paul Daley in 2015, Memorial Director Brendan Nelson said he was thinking about ‘some sort of special exhibition’ in 2018 on Australia after World War I. That undertaking has been partly fulfilled with After the War, showing at the Memorial from October 2018 for 12 months.

The exhibition is not just about after the Great War, however, but after lots of our wars – both major ones, Korea, Vietnam, Timor, Afghanistan, and others. So, perhaps the Memorial has over-delivered. It is not clear whether the broader coverage is for philosophical reasons – the aftermath of all wars is much the same – or simply because the Memorial’s holdings on the Great War alone were a bit thin.

Visitors enter the exhibition (downstairs in the Memorial) past a Charles Bean quote from 1918 – ‘The last gun has sounded’ – and an explanatory paragraph: ‘This centenary we reflect not only on the aftermath of the First World War but also on the cost and consequences of all conflicts in which Australians have been involved from 1918 to 2018.’ Next, we hear the taped voices of eight World War I veterans, including Alec Campbell (strangely here called ‘Alex’) and Ted Smout, the last and almost the last of their generation. Somewhat confusingly, the voices are juxtaposed with Bryan Westwood portraits of elderly World War II veterans, as well as one of Campbell (here correctly labelled ‘Alec’) and another World War I man.

If you spare the time to take them in, the messages of the paintings and the voices are much the same, though, whether they are conveyed in the reminiscences of the Great War men or in the faces of the next generation: war is a bloody awful beast and those who ride it suffer. Nearby, to remind us (although not well captioned) is the wheeled bed that Albert Ward spent decades ‘living’ in, having returned injured and incapacitated from the Great War. (This artefact had been lent to the Melbourne Museum for its Love and Sorrow exhibition.)

Moving further in, After the War offers an interesting display of items similar to those found elsewhere in the Memorial – diaries, letters, official documents, photographs, relics, and so on – with some audio-visual material, including a most effective – and affecting – pair of time-lapse photographs of war cemeteries, next to a wall of photographs of Great War servicemen.

So far, so much as usual for the Memorial. (See the review of the Memorial’s Anzac Treasures book, published in 2014.) Where this exhibition gains power, though, is in the themes under which the relics are loosely grouped and the questions that are posed. The themes: ‘Victory at a Cost’; ‘Rebuilding and New Lives’; ‘Minds and Bodies’; ‘Honouring and Remembering’. Some binaries, some synonyms, lurking questions.

Then come the questions (with some of the answers, as portrayed by the exhibition material, though not always how the exhibition has arranged them):

- ‘How do you celebrate a victory that has come at the cost of so many lives?’ (Be careful never to assume that the balance between victory and death is final. There is a letter from Katharine Susannah Prichard after the death of her husband, Hugo Throssell VC, by his own hand in 1933, 18 years after his awarded act of bravery.)

- ‘How do you rejoice at the return of loved ones at the same time that you mourn the death of others?’ (Any old flag will do to rejoice under? A 1945 welcome home banner for Trooper Douglas Dumesny is complete with an Australian Red Ensign, but it is the 1901-03 version, including large six-pointed star. The seventh point was added in 1909.)

- ‘What if your wounds are not visible?’ (Two photographs of female Afghanistan veterans, one with the hint of a smile, the other without even that.)

- ‘How do you rebuild a civilian life after serving in a distant country for months, even years?’ (Can governments help with the rebuilding? There is a 1916 New South Wales government poster, offering land for soldier settlers. But was dairying really a possibility around Hillston, as the poster suggests? Maybe governments were not much help after all. Katharine Susannah Prichard, see above, also mentioned the lack of support from governments.)

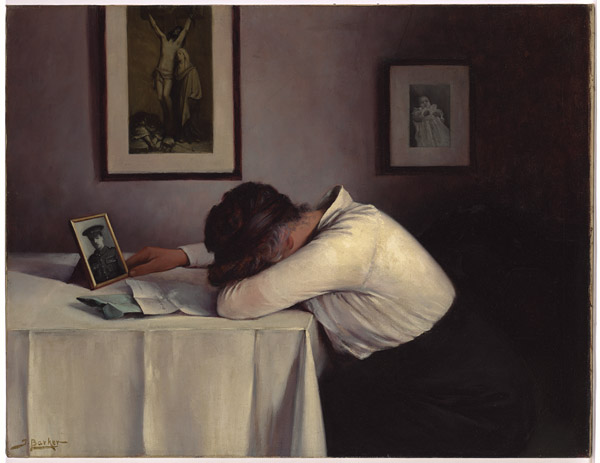

- ‘How do you honour the memory of a loved one?’ (A question confronting the woman in John Barker’s painting, ‘Sorrowing mother’. She has just received the dreaded telegram. What happens next? Will her son’s photograph and, perhaps, medals be repositioned next to his portrait as a baby? ‘They shall grow not old …’)

- ‘What if you did not know exactly how or where they died?’ (Korean War soldiers, John Saunders and Lionel Terry, went missing in action 1953. Terry’s father refused to believe his son would never come home. My uncle died on an uncertain date, missing in action in Malaya in 1943; I suspect my grandfather, a stern sort of gent, was more pragmatic than Terry’s about the prospect of his eldest son’s return. Families differ.)

- ‘How do those left at home welcome back someone who has seen and experienced things they can barely imagine?’ (The syntax there needed some work but, with the sentence rearranged, it is a crucial question.)

- ‘How do you summon fortitude on the road to recovery?’ (There are four portraits of Afghanistan veterans, two of them with prosthetics, another with wounds to the face and arms, a fourth with a ‘thousand yard stare’.)

- ‘Where do you turn for treatment and support after serving in a war?’ (Look at the display of artificial limbs from World War I. And Albert Ward’s bed. There is also a note about Jarrad Brown, commando, Iraq and Afghanistan veteran and suicide, one of more than 400 veterans since 2001 who have survived combat, to then take their own lives)

‘Sorrowing mother’, John Barker, UK, c. 1916 (National Gallery of Australia: NGA 2005.258)

‘Sorrowing mother’, John Barker, UK, c. 1916 (National Gallery of Australia: NGA 2005.258)

These are all awkward questions, and they lurk beneath the often superficial and repetitive renditions found elsewhere in the Memorial and telling of how Australians fought – and how well they fought and how sadly some of them died. Perhaps some of the answers to the questions will be found in the musical offerings the Memorial has put out in association with the After the War exhibition.

Yet proper answers to these questions – if they are to be found at all – require time to reflect, and that is usually what visitors to the Memorial do not have much of. Nor do they seem to descend the stairs in numbers to look at After the War. On our two visits the exhibition was almost empty, compared with the crowds upstairs. The Memorial has done so well for so long the job of emotionally connecting us to relics of how we fought that it has steered us away from questions like those put in After the War, questions that focus on the much more important issues of why we fought, whether it was worth it, and what happens next. That is a pity.

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book (2017).