‘For Our Country: Australian War Memorial sidles a little closer to a balanced view of Indigenous warriors’, Honest History, 31 March 2019 updated

Update 23 April 2019: Graeme Dunstan of Peacebus examines the meaning of the artwork and the words used by the Memorial about it. He refers to a ‘conspiracy of silence’.

Update 12 April 2019: Indigenous artwork unveiled at Defence alludes to Indigenous defence of country. There is a sister work at the Australian War Memorial.

Update 12 April 2019: Henry Reynolds in Meanjin:

The announcement of a grant of half a billion dollars to the Australian War Memorial for a massive program of extensions has reignited the long-smouldering controversy about frontier conflict. Despite criticism reaching back many years the memorial has steadfastly refused to admit Aboriginal warriors into the shrine, which director Brendan Nelson calls the soul of the nation.

***

It has been a question in the history discipline for a while whether recognition of Indigenous service in the King’s and Queen’s uniform takes us closer to or further away from recognition of Indigenous service out of uniform, that is, in the Frontier Wars from 1788 when, by some estimates, more Indigenous men, women and children died than Australian service people died in our overseas wars since 1901. While Honest History has followed with interest the twists and turns taken by the Australian War Memorial in relation to Indigenous service, we are still agnostic on that crucial question.

The question came to the fore again last week when the Memorial unveiled in its grounds a new sculpture wall by Indigenous artist Daniel Boyd and Edition Office Architects. (Canberra Times report. SBS report. Indigenous Affairs Minister’s press release. More from the Memorial.) The explanatory plaque, under the Australian, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags, uses words similar to those often used by Memorial Director Brendan Nelson. (His speech on this occasion.)

For Our Country proudly honours the military service of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Only four or five generations after the arrival of the British First Fleet, having endured discrimination, brutal social exclusion, and violence, many Indigenous Australians denied their Aboriginality and kinship to enlist, serve, fight, suffer and die for the young nation that had taken so much from them. Having enlisted from a desperately unequal Australia, many found military service to be their first experience of equality. In Australia’s defence forces, they were equals – equal in life and equal in death.

A little further over there is a well-known quote from Indigenous soldier, Captain Reg Saunders, which ends thus: ‘We were the first defenders of Australia … we did and we suffered very badly for that – decimated to hell’. People viewing the sculpture wall, rapidly taking in its various features, might pick up some hints from these words and perhaps even ask some questions. ‘Violence’: was it just before the Indigenous men enlisted or did it go back further? What does he mean ‘decimated’? What is meant by ‘taken so much from them’?

The present author made a similar point when reviewing the For Country, for Nation exhibition at the Memorial. (The exhibition is now on tour.) In my review, I picked up some of the words in the exhibition’s captions that dropped hints:

So, there are allusions and hints aplenty in For Country, for Nation, but very little detail (particularly by comparison with how the Memorial deals with Australia’s overseas wars). Even the most obtuse visitor should be left with questions: ‘Suffered’ how? ‘Decimated’, where and to what extent? Protecting and defending Country against whom? (There is a display of traditional weapons, but no indication of how they were used, particularly after 1788.) In ‘battles’ named what? How many people died or were injured? Or were the battles better described as ‘massacres’, given the relative kill counts, perhaps more than 30 Indigenous Australians dead for every one settler?

Emily Gallagher’s review of the exhibition came to like conclusions.

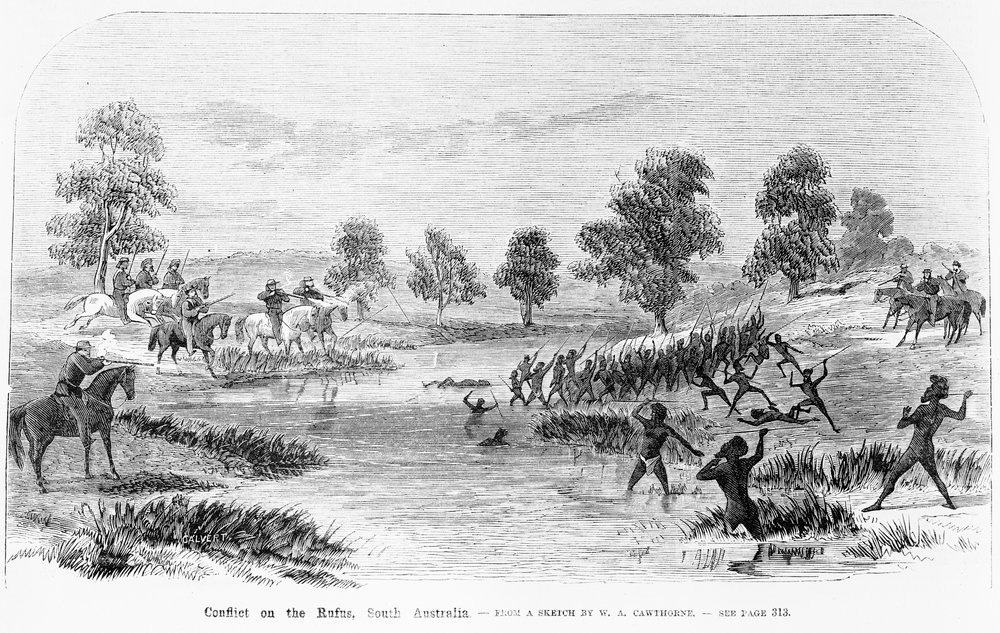

Rufus River Massacre, near Wentworth NSW, 1831, where at least 30 Aboriginal people were killed (SLV/Samuel Calvert)

Rufus River Massacre, near Wentworth NSW, 1831, where at least 30 Aboriginal people were killed (SLV/Samuel Calvert)

For Country, For Nation is the closest the Memorial has previously come to recognising the reality of the Frontier Wars. I tracked its later ‘two steps forward, one step back, a shuffle sideways’ progress here, discussing the Memorial’s purchase and display of expensive art works depicting massacres of Indigenous Australians. There is also a list in the Memorial’s media release last week of a number of steps in its journey. For Country, for Nation generated a book, and another one, Our Mob Served, was launched last week, with a few pages at the beginning about Indigenous service in the Frontier Wars.

The questions I asked in 2017 about For Country, for Nation are still relevant as we stand in front of Daniel Boyd’s wall:

- Can defending Country at home only be recognised to the extent that it can be presented as a precursor to uniformed service after 1901?

- Why should the massacre stories passed down through Indigenous families not be told to the Memorial’s largely white Anglo-Celtic visitors?

- If the desire to serve, to defend Country, is the same now in 2017 (and since 1901) as it was in colonial times, and is recognised as such, it could reasonably be asked: Why is Indigenous defence of Country in colonial times not commemorated in the same way as Indigenous defence of Country now?

There are plans for Indigenous people to deposit soil from Country into the sculpture wall. It would be interesting to interrogate the thoughts of the people who attend on these occasions. Do they see recognition of Indigenous uniformed service as an end in itself? Do they see it as the best they can expect from whitefellers? Do they worry that playing up their willingness to serve the King and Queen, their willingness to deny their Aboriginality, despite all that was done to them, belittles rather than enlarges them? Could they be concerned that whitefellers might think: ‘If blackfellers still fought for us after all that, why should we regret what we did to them?’

Boyd’s work itself is perhaps a little underwhelming until you read this sentence on the explanatory plaque: ‘The thousands of clear lenses [in the work; see illustrations at links above] represent our perception, highlighting our incomplete understanding of time, history and meaning’. There’s a more fruitful hint in that sentence than in some of the others that have littered this tortured process at the Memorial. Perhaps our understanding may gradually become more complete and our presentation of it less free of hedging and prevarication.

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book (2017). That book includes a chapter by Paul Daley ‘Our most important war: The legacy of frontier conflict’ where Daley writes: ‘The memorial has, I believe, occasionally used the black Diggers narrative as a fig leaf to distract from its intransigence on the Frontier Wars’.