‘The Russian Revolution, world history and Australia’, Honest History, 18 February 2015

David Stephens reviews David North’s The Russian Revolution and the Unfinished Twentieth Century (and notes the same author’s In Defense of Leon Trotsky)

Elsewhere on this website historians as diverse as Ann Curthoys and Marilyn Lake, Stuart Macintyre and Gregory Melleuish (scroll down to comments) all put in a word or more for the study of world history. They suggest that familiar tunes in Australian history (Gallipoli, gender, immigration, Western civilisation) sound different when we look for harmonies beyond our shores. A world history approach can drive out self-referential (and self-reverent) parochialism of the sort that is certain to bedevil the celebrations of the centenary of Anzac.

On the face of it, a book titled The Russian Revolution and the Unfinished Twentieth Century, written by a disciple of the prophet of world revolution, Leon Trotsky, promises to deliver a dose of this desirable broader perspective. And so the book does, to a degree, but it also suffers from its own form of parochialism – the need to (sometimes ferociously) score points in stoushes within socialist circles and against outside opponents. (‘Kolakowski’s assertion testifies to the intellectual bankruptcy and cynical indifference to historical facts that underlies the claim that there existed no alternative to Stalinism.’)

David North is the chairperson of the Socialist Equality Party (US) and of the World Socialist Web Site. He has written a number of books on aspects of Marxism and on United States politics. The essays and lectures in the book under review ‘were, for the most part, developed in opposition to the claim that the dissolution of the Soviet Union had brought to a conclusive end the epoch of world socialist revolution’.

The essays cover the October Revolution of 1917, whether there was an alternative to Stalinism, the Moscow Trials and aspects of American history in the 1930s, Trotsky and socialism, reform and revolution in the epoch of imperialism, the hostility of trade unions to socialism, postmodernism, Lenin’s writings, the 1848 revolutions, a collection of documents from 1917, the Fourth International, Germans under Hitler, the causes and consequences of World War II, history as propaganda (with special reference to current events in Ukraine), and Marx’s philosophy.

The essays cover the October Revolution of 1917, whether there was an alternative to Stalinism, the Moscow Trials and aspects of American history in the 1930s, Trotsky and socialism, reform and revolution in the epoch of imperialism, the hostility of trade unions to socialism, postmodernism, Lenin’s writings, the 1848 revolutions, a collection of documents from 1917, the Fourth International, Germans under Hitler, the causes and consequences of World War II, history as propaganda (with special reference to current events in Ukraine), and Marx’s philosophy.

Much of the book is meat for specialists and well beyond the capacity of a non-specialist to review. One wonders, though, whether even specialists will be interested in the Appendix, a collection of 1996 letters to and from North about a review by historian Richard Pipes of General Dmitri Volkogonov’s biography of Trotsky. The letters seem to be mostly about whether Trotsky ever advocated the assassination of Stalin. Their relegation to the Appendix is appropriate.

North’s chapter on World War II sees the two world wars ‘as interconnected stages in a single historical process’ which cost 90 million lives.

The eruption of the First World War arose out of inter-imperialist antagonisms generated by the emergence of powerful capitalist states that were dissatisfied with the existing geopolitical relations. Germany resented its inferior position in a world colonial system dominated by Britain and France, and chafed against the restraints placed on the pursuit of its interests by these powerful rivals.

Of course, other analysts have said similar things recently, comparing the geopolitics of 1914 with that of today. But, in a country like Australia whose consideration of wars is still much more focused on deaths (of uniformed Australians) and derring-do than on global dynamics it is important that we underline such remarks, as well as the overall death counts, civilian as well as military, which are not nearly as familiar to us as they should be but which North sets out with great clarity.

In the chapter on the Ukraine, too, Lenin’s guru on imperialism, the Englishman, JA Hobson, makes timeless points about motivations and the need for scepticism about them. (The interpolations in brackets are North’s.)

It is precisely in this falsification of the real import of motives that the greatest vice and the most signal peril of Imperialism reside. When, out of a medley of mixed motives, the least potent [i.e., “human rights” and/or “democracy”] is selected for public prominence because it is the most presentable, when issues of a policy which was not present at all to the minds of those who formed this policy are treated as chief causes, the moral currency of the nation is debased. The whole policy of Imperialism is riddled with this deception.

Readers will be able to recall plenty of examples of the selection of ‘presentable’ motives by great powers like Britain (civilise and Christianise primitive people), the United States (spread democracy) and Russia (protect ethnic Russians). It is worth, however, also applying the Hobson motives template to remarks from representatives of lesser powers. Read these words from prime minister Abbott in March 2014, when he was welcoming Australian soldiers home from Afghanistan.

Like your forebears, who fought militarism, who fought Nazism and Fascism and who fought Communism, you have fought for the universal decencies of mankind – the rights of the weak against the strong, the rights of the poor against the rich and the rights of all to strive for the very best they can. That’s what Australians do; we always have and we always will. Australians don’t fight to conquer; we fight to help, to build and to serve.

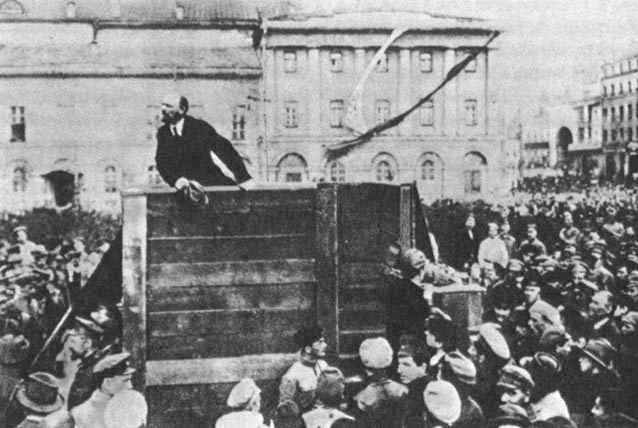

Lenin, Sverdlov Square, Moscow, 20 May 1920; Trotsky and Kamenev removed in second photo (Wikimedia Commons, original, censored)

Finally, as we consider over the next four years the perennial war-related question ‘Was it worth it?’ a passing remark from North is worth pondering. He notes that the Great War came to an end rather abruptly, after the October Revolution in Russia, working class unrest in Germany, mutinies in the French and German armies, and morale issues everywhere, partly countered on the Allied side by the injection of American men and materiel. ‘What brought the war to an end’, North says, ‘was related more to changing political conditions within the belligerent countries than to results on the battlefield’. Again, not new analysis but worth highlighting in an environment where the exploits of Australians in khaki are in sharp focus.

As noted above, this is by no means North’s only book. The year 2013 saw the publication of a revised edition of his In Defense of Leon Trotsky. The book includes refutations of two Trotsky biographies by Geoffrey Swain (2006) and Ian Thatcher (2003), some vigorous whacks at Robert Service’s Trotsky: A Biography (2009) and at Professor Service himself, and some additional lectures by North. There is much in this book, too, for subject matter experts but even the most general of readers will note Trotsky’s claim in 1905 that ‘capitalism has converted the whole world into a single economic and political organism’. That remark scores highly for both perspective and prescience.

Meanwhile, the news items on the World Socialist Web Site are a useful corrective and additive to the Main Stream Media – provided one can avoid being dragged up the occasional ideological dry gulch. Of course, the MSM itself has its fair share of such gulches, even if the ideology lurks a little further beneath the surface.