Chris Roberts & Peter Stanley[*]

‘Monash: myth and reality’, Honest History, 15 August 2018 updated

[This article appears just after the centenary of the Battle of Amiens and of the conferring of Monash’s knighthood. Other relevant material on the Honest History site includes Andrew Richardson’s review of books by FitzSimons and Dando-Collins about the earlier Battle of Hamel, plus material to be found via our Search engine under ‘Monash’. There is also Peter Stanley’s chapter in The Honest History Book and a section in his book Bad Characters, where he describes the mutinies that occurred in Monash’s Australian Corps in the final weeks of the war. Back in April, Neil James of the Australia Defence Association had a very balanced and judicious article in The Strategist. Longer version on the ADA website. HH]

***

A century after the AIF’s greatest successes, Australians rightly remember the achievements of the Australian Corps and its commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. But over the past decade, boosting books lead Monash’s admirers to now claim that he alone devised the strategy and tactics that won the Great War on the Western Front. How do these claims compare with the historical evidence?

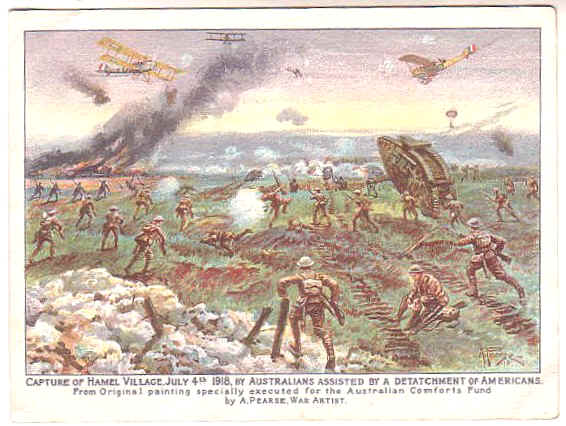

Monash, his adherents contend, first developed the tactic of the limited objective – a short advance that stopped before resistance hardened – commonly known as ‘bite and hold’, and at Hamel (4 July 1918) he orchestrated tanks, infantry, artillery, and aircraft into the ‘combined arms’ doctrine that underpinned success. This is the most prevalent claim about Monash; the truth is more complex. Monash himself said he was not an innovator, but took the best ideas and incorporated them into his own plans. The evidence bears him out.

Hamel, July 1918 (History Council NSW/Australian Comforts Fund/A. Pearse)

Hamel, July 1918 (History Council NSW/Australian Comforts Fund/A. Pearse)

British and French commanders had aimed for more limited objectives in 1915, adopting the idea in the 1916 Somme offensive, and at Messines in 1917. The development of combined arms tactics followed suit, with aircraft, artillery and infantry working together in 1915 and 1916 as the French and British struggled to overcome a strong, highly trained and well-entrenched enemy. British doctrinal and training pamphlets issued from late 1916 reflected the continuing evolution of these tactics, including the use of tanks during 1917.

As Australian historians Trevor Wilson and Robin Prior have concluded, combined arms tactics were well advanced across the British Empire forces by the time Monash became a corps commander in mid-1918. Rather than being the inventor of this evolution, Monash was its beneficiary. At Hamel he certainly refined co-operation between tanks and infantry, but he did not invent these tactics.

Some devotees have praised Monash’s plan at Hamel as a battle that ‘changed the world’. Successful though it was, in reality Hamel was a small-scale action to straighten the Australian line, where ten Australian battalions, supplemented by four American companies, struck five weak German battalions occupying rudimentary defences. The great offensives of previous years and the German offensives during the spring of 1918 had depleted the German army by the time Hamel was launched.

Monash has also been credited with devising the concept for the great Anglo-French offensive at Amiens on 8 August 1918 – the German army’s celebrated ‘Black Day’. The reality is again different, something known since the relevant volume of Charles Bean’s Australian official history appeared in 1942. Foch, the Allied supreme commander, had conceived the offensive as early as April, but had to wait until the German offensives had run their course in July. Even as Monash was considering the possibilities after Hamel, Foch, Haig – British commander-in-chief – and Rawlinson – commander of the British Fourth Army – were developing the plan.

As a corps commander, Monash was excluded from these higher-level deliberations. Working within the constraints of the Fourth Army plan, he was responsible only for the Australian role within it, being one of seven allied corps attacking at Amiens.

The winning strategy during the latter half of 1918 can be attributed to Foch, who conceived the idea of repeated blows from different sectors. As one blow ended, another would begin. This prevented the Germans from effectively deploying their reserves and kept them off balance as the Allies – British, French, American, and Dominion forces – drove them back to defeat.

A persistent myth claims that Monash was considered as a successor to Douglas Haig as British commander-in-chief. The respected Monash authority, Peter Pedersen (Monash as Military Commander), utterly rejects this view. Monash was never considered for the appointment. As a newly promoted corps commander it would have entailed him being elevated two levels over a dozen competent and more experienced commanders to the highest position in the British army, at the very time it was winning a great victory. The myth arises from wartime Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s self-serving War Memoirs, written in the 1930s, and was a means of vilifying Haig, whom Lloyd George detested.

A more recent claim is that Monash conserved his men’s lives. But Monash drove the Australian Corps – and himself – hard, almost to exhaustion. Pedersen judged that

Monash could also be ruthless. As a divisional commander he had no hesitation in bringing down a barrage to retain ground won despite the possibility that his own men might be underneath it. He was willing to sacrifice entire units for a greater object … [He rejected] the pleas of others that their troops were incapable of further effort …

During the capture of Mont St Quentin, Monash ordered an attack with the words ‘casualties no longer matter’. The 34 000 Australian battle casualties between early July and early October 1918 under Monash compare with the 34 000 over three months at Third Ypres (Passchendaele) in 1917. While the territorial gains in late 1918 were significantly greater, the opposition was considerably weaker.

Admirers also contend that Monash, with his fine engineer’s mind, brought to battle planning a level of sophistication not seen before. It is true he took extreme pains to ensure the detail was correct, notwithstanding his staff also contributed to the planning. Nonetheless, there is abundant evidence in documents, orders and correspondence that other commanders had adopted the same meticulous approach.

General Sir Ivor Maxse (Wikipedia)

General Sir Ivor Maxse (Wikipedia)

Monash was an outstanding corps commander, but there were others as competent and effective – Maxse, Cavan, Jacob and the Canadian Currie – who had learned the lessons of 1915-17. As Geoffrey Serle, Monash’s greatest biographer, perceptively wrote, ‘Monash perhaps won more than his fair share of fame, as against other Australian generals, for he had the great luck to take command of a magnificent fighting body just when the tide was about to turn conclusively in the allies’ favour’.

It is time we outgrew the immature chauvinism of unduly exaggerating Australian achievements and claiming credit for other nations’ efforts. It trivialises the fine achievements of the AIF and Monash, doing both a great disservice. Rather, in acknowledging the efforts of the AIF and Monash, we should recognise that victory in 1918 was achieved through an enormous Anglo-French-American effort in which Australians played a highly commendable but hardly decisive role.

[*] Brigadier Chris Roberts is a Visiting Fellow at UNSW Canberra and the author of The Landing at Anzac, 1915 and other works. Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is the author of over thirty books, including Men of Mont St Quentin (2009).