John Moses*

‘Red professor in a cold war’ (review of Monteath and Munt), Honest History, 28 October 2015

John Moses reviews Red Professor: the Cold War Life of Fred Rose, by Peter Monteath and Valerie Munt

In an extensively researched work, lucidly written and judiciously argued, Peter Monteath and Valerie Munt have sensitively portrayed the remarkable life of the English-born, Cambridge-educated Australian anthropologist, Frederick Rose (1915-91). The authors trace Rose’s career with harrowing honesty, if not with unrelieved admiration.

As an anthropologist driven by a compassion for the plight of Australian Aborigines, and the conviction that the ideology of Marxism-Leninism was the only means by which humanity could be rescued from the deleterious impact of capitalism, Fred Rose was a flawed heroic figure. As well, the anti-hero depicted here was subject to all the frailties of the flesh that men are heir to, not only through his frequent adultery towards his German-born wife Edith Linde, but also through the betrayal of members of his own family to the notorious East German secret police, the Stasi.

As an anthropologist driven by a compassion for the plight of Australian Aborigines, and the conviction that the ideology of Marxism-Leninism was the only means by which humanity could be rescued from the deleterious impact of capitalism, Fred Rose was a flawed heroic figure. As well, the anti-hero depicted here was subject to all the frailties of the flesh that men are heir to, not only through his frequent adultery towards his German-born wife Edith Linde, but also through the betrayal of members of his own family to the notorious East German secret police, the Stasi.

Rose had been recruited as an informer soon after he had chosen to migrate to the German Democratic Republic in 1956 with the blessing of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), of which Rose had been a member in good standing since 1942. In his subsequent behaviour Rose manifested all the zeal of the devoted convert to a cause which he fervently believed was the incontrovertible truth.

The fascinating thing about zealots is that they can subordinate humane values to the objectives they believe in, and what the world has learned – and is still learning to its sorrow – is that Marxist-Leninist regimes, while marching under the banner of the liberation of humankind from wage tyranny, are in practice the most brutal and ruthless forms of government, outdoing even National Socialism in many if not all respects.

A wise Israeli historian, Professor Walter Grab (1919-2000), himself a former Communist, confided to me once an old Yiddish saying about human nature: ‘Men strive for three things in this life, namely wealth, power and/or fame’. It is, of course, incontestable that some people devote themselves to the amassing of great wealth for its own sake. Others strive for power and go into politics and, finally, others again achieve fame, or at least reputation, in the pursuit of knowledge or even in acts of altruism.

This last category covers people who believe they have discovered the stone of wisdom, which is what the Marxist-Leninists ideologues declared their system to be. In the official Handbuch des Marxismus-Leninismus, which all students in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) were obliged to own, the first chapter appeared under the heading, ‘Die Lehre des Marxismums-Leninismus ist allmächtig, da sie wahr ist’. (‘The doctrine of Marxism-Leninism is all powerful because it is true.’) That is, of course, as fervent a declaration of faith as one might imagine is expressed in any religious creed.

Nowhere in this biography is there any mention that Rose had ‘read, marked, learned’ any of the major publications of either Marx or Lenin. It is, however, stressed that Rose embraced communist ideology wholeheartedly after witnessing the successful Soviet resistance to Nazi aggression. Indeed, as a student at Cambridge in 1935, Rose had visited Germany and, due to an irregularity in changing money in Mainz to assist Jews to escape, he was arrested and incarcerated for over two weeks in a Nazi gaol and fined 800 Marks. As the Soviet Union was the chief means of ridding the world of the scourge of fascism and racism, the idealist in the young Rose was awakened; he became in time an ardent communist.

It is to the great credit of Monteath and Munt, both of Flinders University, that they have erected a literary monument to the memory of a champion of the rights of Aborigines, indeed, a scholar whose life’s work as an anthropologist would have otherwise been totally forgotten. In tracing Rose’s life from Cambridge to Melbourne, the Northern Territory (Groote Eylandt) to Canberra, the wharves of Sydney and finally to East Berlin, the authors have not only portrayed a gifted and complex personality, but have also thrown light on both Australian politics under the prime ministership of RG Menzies and the grim realities of life in the GDR.

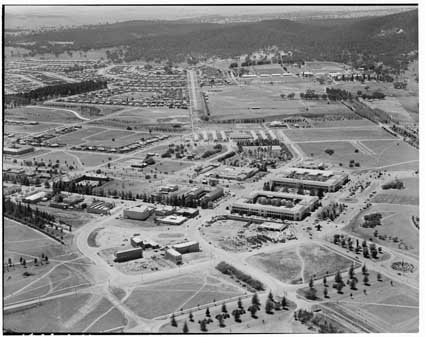

Fred Rose’s Canberra, 1956 (National Archives of Australia A7973, 11224914)

Fred Rose’s Canberra, 1956 (National Archives of Australia A7973, 11224914)

Of course, there is much to admire about Rose, his dogged determination and devotion to the emancipation of a downtrodden people, his undoubted sense of justice and his penchant for hospitality and conviviality. And, if one could sympathise with his embrace of a totalitarian ideology, one might also admire Rose’s faith in that system. It was, indeed, a widespread conviction among some people that Soviet-led world-wide communism could ultimately deliver on the challenge to create a society on earth in which, as Marx projected, goods would be produced solely for human needs and not for surplus value, which only accrued to the benefit of the bourgeoisie.

Rose was dedicated to this proposition and obviously approved of the means necessary to bring socialism about, namely revolution to establish the dictatorship of the proletariat. Therein lay an insurmountable problem, the need for ultimate violence to sweep away the ruling classes in order to create social relationships which would liberate the working class from wage slavery and prepare the way for the evolution of a ‘new species being’, as Marx promised.

In this regard it is ironic that the Cambridge-educated intellectual who – via his membership in the CPA and through actually becoming a Sydney waterside worker, where he befriended the redoubtable Jim Healy (1898-1961), the union secretary – found his way to East Berlin, capital of the GDR, then under the Stalinist dictatorship of the notorious Walter Ulbricht. It was there, after being required to jump through seemingly endless bureaucratic hoops, he finally became a professor of anthropology at Humboldt University, even though his command of the German language was only fragmentary. Rose’s major work, the study of the kinship relationships of the Groote Eylandt Aborigines, was published in English and resulted in a high degree of recognition if not universal approbation.

A key element in this unfolding saga was that Rose was already a member of the CPA at a time when Prime Minister Menzies, through the agency of ASIO, was hell-bent on making the CPA an illegal organisation. For this purpose he held in 1951 his famous but failed referendum. That was followed in 1954 by the Petrov Affair which revealed that the Soviet Union had maintained a spy network in Australia. As Rose was long suspected by ASIO of being a communist spy he was called upon to testify to the Royal Commission on Espionage 1954-55.

Rose could not be implicated in Soviet subterfuges but any prospect of furthering his academic career in Australia was shattered. Never would he have dreamed that it might be re-born in the GDR.

The puzzling thing about Rose was his uncritical approval of Soviet aggression as, for example, at the time of the 1968 Prague Spring. On these inhumane military interventions, endorsed also by the GDR, he maintained a grim silence. The same uncritical loyalty towards the East German regime was manifest in his readiness to act as a Stasi informer against members of his own family. This was not an isolated phenomenon, as is revealed in much of the literature that has come out on the GDR.

So there was a dimension in Rose that enabled him to sanctify violent and essentially dishonourable acts in a doctrinaire manner by prioritising the objectives of the communist party. These were governed by the so-call absoluter Wahrheitsanspruch – the claim to possess the absolute truth to which all other claims, such as those of Christianity, for example, were irrelevant. The Party could get away with murder if the Politbüro deemed it necessary.

How Rose could endorse such a position is noted by the authors with astonishment. It is admittedly difficult to explain such behaviour in someone who is otherwise a very logical thinker. Rose, of course, lived long enough to experience the collapse of communism in Europe, so it must have been obvious to him, as it was to thousands of others, that his espousal of Marxism-Leninism as a panacea for the world’s ills was a gigantic error of judgement. In the end, he suffered the fate destined for fundamentalists of all provenances.

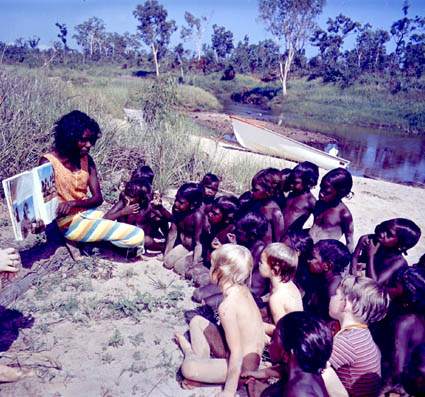

Outdoor class, Groote Eylandt 1975 (National Archives of Australia A8746, 11341721)

Outdoor class, Groote Eylandt 1975 (National Archives of Australia A8746, 11341721)

Rose had been able to make subsequent visits to Australia hoping to further his anthropological research but, not unexpectedly, he met with bureaucratic obstruction. Despite this, however, he was able to publish valuable works that deepened knowledge about Aboriginal living conditions and brought them to public attention. He clearly believed fervently in this aspect of his life’s mission.

The authors, by their timely research, have placed in their debt not only the anthropological community but also all historians of contemporary Australia and those who remember the chilling time of the Cold War. One can only wish this considerable work the widest possible circulation.

* Reverend Dr John A. Moses is a historian of Germany and Europe and an ordained Anglican priest.