Michael Piggott*

‘Time for something from the heart, from and for all of us: Mark McKenna’s Quarterly Essay 69’, Honest History, 10 April 2018

Michael Piggott reviews Mark McKenna’s Quarterly Essay 69: Moment of Truth: History and Australia’s Future

Sixteen pages into this essay, Mark McKenna mentions Anzac Day, Australia Day and the issue of Australia becoming a republic. Then he observes that these debates and histories ‘circulate in parallel universes’. But, as he’d already hinted, he then declares the essay’s aim as ‘an attempt to bring them together’.

Sixteen pages into this essay, Mark McKenna mentions Anzac Day, Australia Day and the issue of Australia becoming a republic. Then he observes that these debates and histories ‘circulate in parallel universes’. But, as he’d already hinted, he then declares the essay’s aim as ‘an attempt to bring them together’.

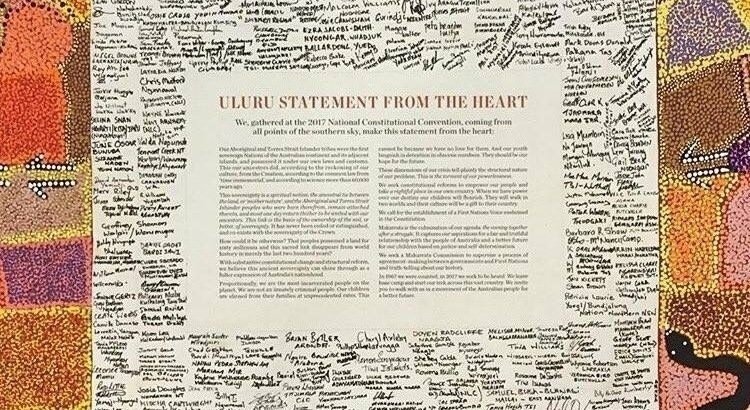

In another sense, the essay is an extended reflection on the meaning, background and implications of the Uluru Statement from the Heart issued in May 2017 and reproduced at the front of the essay. Five months after it was issued, the Statement was imperiously dismissed by the Prime Minister, whom McKenna loves to name in full: Malcolm Bligh Turnbull.

In framing his essay with the themes of Anzac, 26 January and republicanism, McKenna is on familiar ground, which he has already traversed in publications such as This Country: A Reconciled Republic? (2004), ‘Lest we inflate: why do Australians lust for heroic war stories?’ The Monthly (December 2012-January 2013), ‘More than an excuse for a long weekend – how we came to love Australia Day’, The Conversation (26 January 2012), and his chapter (‘King, Queen and Country: will Anzac thwart republicanism’) in The Honest History Book.

This new essay, however, can readily be seen as a distillation of practically all McKenna’s previous writing and research interests, including the prize-winning titles Looking for Blackfellas’ Point: An Australian History of Place (2002) and From the Edge: Australia’s Lost Histories (2016). Even Manning Clark has a walk-on moment in the essay, having been the biographical subject of McKenna’s other award- winning book, An Eye for Eternity (2011).

Even given all these precursors, the essay remains an extended commentary on the Uluru Statement, past efforts at reconciliation, and why, if the Statement was understood and accepted, the essential conflict and skewed allegiances within what Mick Dodson calls (we learn at page 15) ‘the Australian psyche’ could begin to be resolved. If the vision of a new redeeming national narrative were indeed achieved – one which embraced what the Statement termed a ‘First Nations Voice’ sanctioned by the Australian Constitution and ‘truth-telling about our history’ – the problematic status of Anzac Day and Australia Day and what kind of republic all become less intractable. As McKenna explains:

The Uluru Statement’s invitation to ground the Commonwealth’s sovereignty in the ancient sovereignty of Indigenous Australia goes to the heart of the coming republic … [R]epublicans have imagined that the question of the country’s independence was anchored solely in its relationship with Britain and her monarchy. We have looked outwards rather than within, knowing what we want to reject but being less certain about what we want to create in the monarchy’s absence … [T]he true source of a more mature and independent Australia [is] the grounding of our sovereignty on our own soil, in the songlines and histories of an ancient island continent. (pp. 65-66)

Throughout his essay, McKenna’s appreciation of Indigenous-settler history, and especially the Frontier Wars, is evident. The essay references numerous works, many written in the wake of Henry Reynolds’ scholarship, as well as McKenna’s own Looking for Blackfellas’ Point and From the Edge. But commendably, McKenna acknowledges the work of others, Indigenous and non-Indigenous:

Many writers before me – historians, novelists, lawyers, artists, journalists, theologians, politicians, anthropologists, political scientists and countless more – have grappled with the complex relationship between history, constitutional justice and national legitimacy. This is a collaborative project. And we have to take the long view. (pp. 17-18)

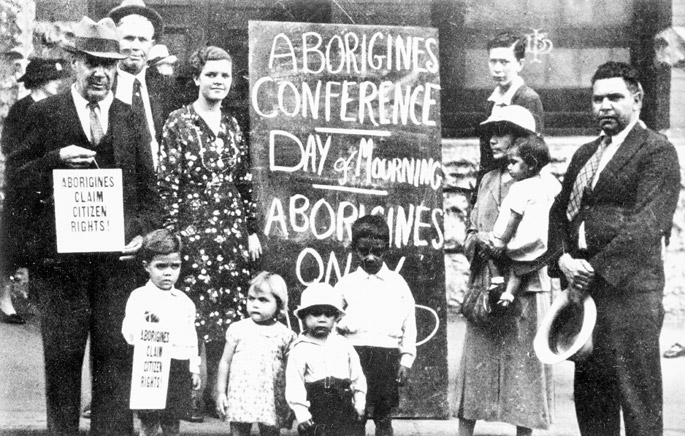

Sesquicentary Aboriginal protest, 26 January 1938 (National Museum of Australia)

Sesquicentary Aboriginal protest, 26 January 1938 (National Museum of Australia)

As an indulgent aside, I’d urge we acknowledge among those ‘countless more’ the creators of often highly subversive screen works, people from film directors to new media artists. This stream was evident over 30 years ago in the brilliant satirical film BabaKiueria, and recently in the many unsettling and poignant installations which were offered in Adelaide as part of the South Australian Art Gallery’s Tarnanthi contemporary Indigenous arts festival.

Like the Uluru Statement, McKenna’s essay too reads as if ‘from the heart’. The writing conveys intelligent empathy throughout, with, to my mind, only one misstep: Australia arranged for the reburial, not repatriation, of solders found in unmarked graves on the Western Front (p. 69). There is anger and exasperation from McKenna, too, especially at the reactions since the Statement was issued.

Believing that pasts can indeed be reconciled, McKenna includes a mini version of the approach he developed in Looking for Blackfellas’ Point and From the Edge. This is in a gem of a section headed ‘The birthplace of modern Australia?’ It covers the way the community of Kurnell, Botany Bay, eventually negotiated an agreed approach to commemorating Cook’s landing. By 2012, local schoolchildren were singing the national anthem in the Dharawal language. A similar rapprochement has been evident further north, as McKenna explained in ‘On Grassy Hill: Gangaar (Cooktown), North Queensland’, in chapter 4 of From the Edge.

***

For this reviewer, two additional ideas discussed in McKenna’s essay especially resonated: ‘truth-telling’ and a National Keeping Place. The former is mentioned in the Uluru Statement, the other isn’t, but both are powerful ideas and full of implication. Before considering them however, some background is needed.

Although the burden of the Uluru Statement is obvious, to many of its readers the Statement will not be self-explanatory. A simple example is its use of italics to indicate quotes. Only in the Referendum Council’s Final Report are the sources (e.g. anthropologist WEH Stanner, Gough Whitlam, the Mabo judgement) identified. On the other hand, the Statement mentions the concept of ‘makarrata’ and asks for a Makarrata Commission. Many people – at first, I admit, myself included – would not know what this meant. (It is a philosophy of conflict resolution and justice-seeking, more complex than a treaty, and used by the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land.) McKenna weaves some explanation through his essay, but, usefully, the Parliamentary Library has issued Uluru Statement: A Quick Guide.

The Uluru Statement was the product of the majority views of a First Nations National Constitutional Convention of over 250 Indigenous leaders, organised by the Referendum Council, who met at Uluru in May 2017. Its ideas drew on a discussion paper and findings of a dozen regional dialogue meetings. The Referendum Council’s Final Report, submitted to the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition in June 2017, led with the Uluru Statement and followed with over 40 pages of elaboration and a dozen appendices. Anyone wanting to properly understand the 440 word Statement (and indeed McKenna’s essay) should read this Final Report. (There is more background here.)

The Uluru Statement sought ‘a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history’. The idea of truth-telling should be widely understood in the wake of Royal Commissions and other inquiries into the Stolen Generations, into the treatment of children (including child migrants in out-of-home care), and institutional responses to child sexual abuse, but also from earlier ATSIC statements. Additional background relates to truth-and-reconciliation processes, best known from South Africa, and the declarations and resolutions of various UN bodies and the Human Rights Council.

Aboriginal prisoners in chains, Coniston, Northern Territory, 1928 (National Library of Australia/State Library of SA)

Aboriginal prisoners in chains, Coniston, Northern Territory, 1928 (National Library of Australia/State Library of SA)

The Uluru Statement did not prescribe the machinery to facilitate truth-telling (beyond an ‘oversight commission’), but occasionally (in the regional dialogues summarised in the Referendum Council’s Final Report and in McKenna’s essay) a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is canvassed. What they and he (especially at pp. 15-19) both stressed repeatedly was the importance of the direct personal voice of testimony being heard. They meant, of course, testimony about matters such as massacres, theft of land, Maralinga, forced removals and stolen wages, as well as resistance, survival and struggles for justice. McKenna (pp. 39-45) quotes extensively from existing published Indigenous oral histories, thus giving a sample of what should be heard.

Truth told orally, transmitted generationally, and often community-based, contrasts in some ways with the conclusions of a lone historian drawing on written archival sources describing and attempting to explain events, perhaps from centuries past with zero personal associations. But debates about the ‘pastness’ of the past and about the relative reliability of sources are irrelevant here. True, they have their own little corner of frontier wars historiography – illustrated by, for example, the contrasting views in Bain Attwood’s ‘Contesting frontiers; history, memory and narrative in a national museum’ and Keith Windschuttle’s editorial in the March 2018 Quadrant – but McKenna also cites Marcia Langton on Indigenous Australians sharing their oral histories with historians to produce a new story of our shared past. Here, he believes, we can glimpse tentative progress, an acceptance of ‘the relationship between the acknowledgement of history and the re-founding of the nation on more honest, just and legitimate grounds’ (p. 17).

***

McKenna’s second intriguing idea he introduces at the very end: a national keeping place. It comes from neither the Uluru gathering nor the Referendum Council but the Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation’s 2014 National Resting Place Consultation Report. (Guardian Australia’s Paul Daley has also written about the idea.) The Committee urged that a memorial be established in Canberra (specifically at ‘a site adjacent to Federation Mall, within sight of Parliament House’) for poorly provenanced or unprovenanced Indigenous ancestral remains. This idea has been discussed off and on since the early 1990s.

First, the terminology. The Advisory Committee’s Discussion Paper and the survey which preceded its report referred to a National Keeping Place, although the report itself preferred ‘resting place’ so as to ‘better distinguish it from a museum and to reflect its role’ (Report, p. 10). Given that the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies calls itself ‘the great keeping place’ this seems wise. As for our essayist, he consistently uses the rejected label, suggests Reconciliation Place (near the National Library, between Questacon and the foreshore of Lake Burley Griffin) as a better location, and argues for an additional monument, a National Memorial ‘dedicated to the memory of all those who died in the frontier wars’ (p. 72).

Since the Advisory Committee’s report of 2014 there has been silence from the Abbott and Turnbull governments, even though they had provided support for the consultation process. Four years of silence is just plain discourteous; at least the Uluru Statement was officially acknowledged. It is fanciful to think the government believes the 200 hollow log coffins, the permanent installation forming the Aboriginal Memorial at the National Gallery of Australia, render later proposals redundant.

Perhaps McKenna is right to argue for a memorial, something no tourist or international dignitary could miss or misunderstand. An equivalent of the 41 metre high Çanakkale Martyrs’ Memorial on the Gallipoli Peninsula would do it. Canberra ‘is where the nation becomes brick and mortar’ and yet ‘there is a missing piece of architecture’ (p. 72).

McKenna’s essay had opened typically with a personal reaction to place, with the author walking across ‘the vast open spaces’ of the national capital and this observation: ‘If it were not for the Tent Embassy and the easily missed Reconciliation Place, Indigenous Australia would have no obvious presence within the Parliamentary Triangle’. Then let us have something immediately visible added to the inconspicuous Reconciliation Place; something to match the scale of the Australian War Memorial physically and emotionally. But, regardless, something which expresses Indigenous wishes and which is nationally shared and officially accepted – from the heart.

Petition supporting the Uluru Statement (Change.org)

Petition supporting the Uluru Statement (Change.org)

* Michael Piggott AM is Treasurer of the Honest History association and an archivist with many years’ experience. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. The chapter is about the Australian War Memorial and the legacy of Charles Bean. Michael is currently based at the National Library of Australia as a Senior Research Fellow, Deakin University (ARC Linkage project LP 170100222). For his other work for Honest History refer here.