‘On being an independent scholar’, Honest History, 25 July 2014

When Honest History asked me what it was like being an independent scholar, my first reaction was ‘lonely, sometimes frustrating, and very rewarding’. Traditionally, independent scholars are not highly-treasured; they rarely receive acclaim or significant financial reward. It is reward enough to have the freedom to make an honest contribution to the thinking of others.

Charles Darwin suffered the ridicule of that most powerful of institutions, the church, yet he persevered as an independent scholar to win the minds of many, continuing a tradition of independent scholarship that stretches back to Greek and medieval times. It can be a lonely road, however, working without the support of an institution which might promote and publish your work if you are prepared to embrace its thinking and objectives.

Scientist, David Pearcey, shared his experience of being an independent scholar.

The independent scholar is a seeker or discoverer of truth. Truth is hard to track down as it is a natural fault of being human to have a preconceived notion of what the truth may be and thus we tend to seek the truth down wrong paths which do not lead to discovery. Thus the scholar must be honest with him or herself and always be in doubt about their work.

Pearcey reflected that in the academic world independent scholars ‘are treated with disdain’. They are not specialists – professional experts – and may lack links to the academic world. The topic that the independent scholar investigates may trespass across several academic areas where the independent scholar may lack expertise. On the other hand, independents can bring a generalised or multi-disciplinary perspective and ‘trigger exasperation amongst professional academics’. It is this broader perspective, Pearcey says, that gives independents their ‘place in the pursuit of knowledge’. They can discover new approaches to the understanding of a subject which are then followed up by specialised research by professional academics. In science, this happened with Darwin, Einstein, and Alfred Russel Wallace.

There is no reward at the end of the tunnel for independent science scholars [Pearcey goes on] but independent scholars are driven within themselves and do what they do because it is in them. However, the professional academic community will invariably ridicule their work without offering constructive criticism or a professional discussion about the topic (as academics are specialists and may have difficulty dealing with a multi-disciplinary approach).

The Appendix to this article is about the Independent Scholars Association of Australia (ISAA), whose members are largely historians of one sort or another, including scholars in local and regional history, biography, institutional, political and social history, ethnography, and, indeed, science. Human ecologist and ISAA member, Doug Cocks, has thought about what turns a person towards independent scholarship.

Let me push the envelope and further suggest that what distinguishes ISAA people from educated people who are interested listeners rather than scholars (e.g. U3A people) is that they enjoy and seek dialogue with people who have moderately but not radically different world views and similar spheres of interest.

Independent scholars embrace the freedom to pursue knowledge without confine or direction, not beholden to follow an agenda of a funding body or group with a defined project or object. Being an unfunded writer is the price paid to be truly free to read, research, talk and write wherever curiosity or passion takes you.

The advantage that independent scholars have over professional academic researchers [says David Pearcey] is that independent scholars can pursue their research without financial constraints and peer pressures – as they are not being paid – and the way they wish to carry out their work is of their choosing.

It seems clear that ISAA is likely to attract more historians than scientists but, as noted above, this includes historians of science. In Doug Cocks’s view,

ISAA is most likely to find scientist recruits in the historical sciences. I immediately think of cosmogony, evolutionary biology, palaeontology, ecology, geology and geomorphology, archaeology, climatology. In principle, I can see ISAA scientists and non-scientists exploring the overlap between the “two cultures”.

Cocks sees a place in ISAA for scientists with a concern for the future of independent scholarship and for those wanting to explore and present the social and inter-disciplinary implications of their science, something that is not part of their everyday work. He reminds everyone that the future is bleak for all small community-based organisations, especially those with intellectual pretensions. In his recent work he examines the longer term, say several decades, when a ‘new Dark Age’ scenario is plausible.(1) Under the rapidly converging impact of four problems – population growth, resource depletion, global warming and senescent (ungovernable? decaying?) society – we could see a world-wide breakdown in social organisation. In his ‘worst case’ version of this scenario, he suggests that

life for much of the world’s population will be an exhausting wretched struggle punctuated by pain, fear, ill-health and early death. Cities everywhere will struggle to avoid becoming giant lawless slums. Rural populations will be vulnerable to marauders and incursions from displaced persons. There will be no place for civil society.

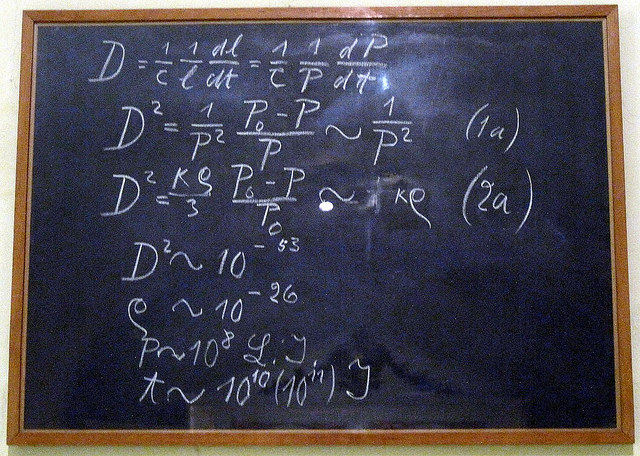

Einstein’s blackboard, Museum of the History of Science, Oxford (Flickr Commons)

Turning to the here-and-now and the imperative to encourage independent scholarship, Cocks suggests that we don’t need scenarios to know that we are in the middle of a cultural transformation, which may or may not be a precursor to social collapse and a ‘new Dark Age.’ We are already living in an era of rapid change, political, economic, social and technological. He gives a few examples: the increasing inability of governments to effect progressive change; rising inequality; resource degradation and exhaustion; individualisation; post-modernism; institutional senescence; the electronic communications revolution.

The point being that this affects us all, writers, artists, historians. Science is no exception. Cocks argues that science in universities, research agencies like CSIRO and government departments is being starved for funds and pushed in short-term utilitarian directions by politicians and bureaucrats who lack understanding of how science works – ‘basically that it is a long-term enterprise’. Australian business also has failed to be a large employer of research scientists.

To cap all this, scientists have lost much of the social standing and authority they had just a few years ago. I sometimes feel that the happiest scientists are retired or in the twilight of careers that have dodged many of these upheavals.

Pearcey, too, has concerns about independent scholars in the sciences. He considers that independents interested in science fall into two groups,

those that are furthering their academic studies now independent from the university system where they earned their living and those who did not undertake university academic research but have a drive in them to investigate scientific work of their own liking.

Independent scholars who are not professional academics and work outside the academic system ‘are probably driven’, Pearcey feels, ‘by a desire to understand new knowledge and gain a feeling of satisfaction within themselves through discovery. There are no financial or honours rewards!’ Another ISAA member places the work of independent scholars in a long-term perspective, which speaks strongly of the phenomenon of ‘standing upon the shoulders of giants’.

It is comforting to think that before the days of high-powered and glamorous tertiary humanities departments – I have no qualification to speak about non-humanities departments – there were already independent scholars. I think of Lord Macaulay beavering away on his History of England in the British Museum’s Reading Room, dreading that closing time which always seemed to occur too early for him.

I think of Monsignor Ronald Knox with his battered old typewriter for rendering his Scripture translations, confounding the visiting journalist from Time magazine who solemnly expected him to have a gaggle of “research assistants”.

I think of – more recently – the late Barbara Tuchman, unaffiliated with any campus, burrowing around in the Paris Archives Nationales and discovering in the process that the surest way to demonstrate her bona fides to any librarians, however intimidating, was to show them the plane ticket for her imminent departure from France. These three authors’ examples suggest that the desire for independent scholarship is still a part of Western thinkers’ DNA and that, while this desire might take forms unimaginable to our grandfathers, it is unlikely to disappear quite yet.

This is the sort of heritage that independent scholars genuinely value and to which they, albeit modestly, aspire to contribute. In an increasingly corporatised and constrained environment this is a worthy objective. Yet there needs to be some ‘push-back’. An independent historian puts it this way:

Scholars, in my view, are only effective if they work in a society in which some people at least understand what they [scholars] are trying to do even if they do not appreciate its value. A common language and culture, the ability freely to converse are essential. At the same time, that thought should not be constrained by directives from powerful individuals with their own agendas. Independence is crucial in research and necessary in making the outcome known to all others. Present institutions like universities are governed by the requirements of those who control the economy; the concept of a long-term public good has been diminished to the advantage of the market place. Groups, however powerless, who can bring together those who are not dependent on such funding and give them a voice are vital if we are not to slip once again into tyranny.

An independent scholar of great note – though of considerable private means – Edward Gibbon, once wrote that independence is ‘the first of earthly blessings’. Independent scholars hope to prove that true for society as much as for themselves.

(1) Doug Cocks, Global Overshoot: Contemplating the World’s Converging Problems, Springer, New York, 2013.

_____________

Appendix: The Independent Scholars Association of Australia

In 1993, Ann Moyal, author and historian of Australian science, technology and telecommunication, put forward the idea of forming an association of independent scholars. She won the support of the committee of Canberra’s Centre for Australian Cultural Studies, then run by historian David Headon. Patricia Clarke, author of many books on Australia’s early literary women, was a Centre member. The Independent Scholars Association of Australia (ISAA) was formed in 1995 and all three founders are valued members of the Association today. (1)

Today ISAA is a network of scholars pursuing interests in the broad streams of the humanities, arts and sciences. Their work is produced in a variety of forms, including book and journal publications, films and documentaries, script writing and journalism. As an association, ISAA has no political affiliations but seeks to encourage all who, independently of institutions, offer well-founded studies of society, in the humanities and the sciences, or ideas of cultural significance. (2)

The Association’s emblem is the Boab tree. The Boab tree is self-sustaining; it draws on its own resources. Upside down, it flourishes against the grain.

ISAA’s purpose

ISAA’s purpose is: to encourage and support individuals who undertake independent scholarly work outside the nation’s formal institutes of education and research; to promote such scholarship; and to stimulate public debate in Australia. It does so by:

- bringing such individuals together to share interests and expertise;

- sponsoring conferences and lectures for both members and the public;

- offering informed opinion on matters of public interest and concern;

- creating a collective voice on issues affecting the practice of scholarship;

- representing the interests of independent scholars in the public arena; and

- supporting knowledgeable dissent and independent opinion.

ISAA’s members

Importantly, ISAA is an inclusive association, not of just independent scholars, but of those who embrace and support independent scholarship and wish to engage in intellectual exchange. Many ISAA members are supported by institutions and many others are full-time or part-time independent scholars. The views of a number of ISAA members are set out below.

1. I remember being attracted to ISAA because of the interesting topics covered in public events. I realise that ISAA is successful because it regularly attracts such a range of high profile and authoritative speakers. ISAA also represents for me an association of thinkers. I know it’s called an association of scholars but the importance of the interesting and incisive thought is foremost rather than the mechanical adherence to academia and scholarship. It brings together people who value interesting investigation of new ideas, regardless of their own professional or interest focus, and allows a collegial approach to public events and publications. I am not a scholar or an academic but have experienced university life and a professional career in the arts before retirement and this I have found has given me an almost automatic ‘fit’ with membership of ISAA. (ISAA member)

2. As an ex-academic who is now undertaking commissioned work, I value ISAA as a substitute for the interdisciplinary insights of ‘corridor chat’ and the general stimulation of exchanging ideas with work colleagues. ISAA members tend to be active and engaged, so are a constant inspiration for all facets of life. (Historian)

3. As a scientist, I value my membership of ISAA because of the links it provides to scholars outside my own field. This is the sort of broad support that university academics take for granted as part of their institution, but independent scholars usually have great difficulty making useful contacts outside their own narrow professional field. (ISAA member)

4. As a secondary school history teacher I both engaged in a broad world view of history and was aware that history can encompass the arts, sciences and the humanities. I was attracted to ISAA by the way all the disciplines could interact and share their particular expertise with a wider audience. I joined ISAA some years before retiring, as part of an overall plan to continue intellectual involvement beyond my working life. Membership provides an Australia-wide community of scholars to belong to, the opportunity to gain insights from people in quite different fields and the chance to explore and extend my own thinking in a stimulating and supportive environment. (ISAA member)

5. As a scholar who has limited connections to either tertiary education institutions or to museums and libraries, ISAA provides me with an invaluable platform for both contributing to, and being in contact with, scholarly diversity and discussion. A scholar is not only a ‘learned person’, but also a ‘person who learns’. (Writer and art historian)

Elevated view of the Melbourne Public Library, c. 1913 (Flickr Commons/State Library of Victoria)

6. Why do I participate as an ongoing ISAA member? There is satisfaction in being in an organisation that sets out to explore ideas, be they in the field of humanities, or science, or political or other. The ISAA talks here in Canberra cover many topics, some quite unknown to me, almost always informative and often provoking discussion. The participants can be intellectually challenging. On the broader scene there has been satisfaction in being on Council, being Treasurer, being able to attend National Conferences, help organise such conferences and participate in the regular chores of running ISAA. (Retired medical practitioner)

7. I am the author of three Australian historical novels successfully published in Australia and Germany. I joined ISAA wondering if, being a writer rather than an academic, I would feel welcome. I soon discovered how valuable and supportive ISAA is. Members are generous in sharing their knowledge. I find it stimulating exploring subjects and ideas outside my own fields of reference. ISAA has expanded my awareness and appreciation of a diverse range of subjects – in a relaxed, welcoming environment, whether at talks in members’ homes or at seminars. (Novelist and ISAA member)

The novelist’s comments reflect my experience. On joining ISAA as a Canberra lawyer and a ‘would-be’ writer I was invigorated by the exchange of ideas between scholars at ISAA’s various local and national forums. I was provided with informal opportunities to speak about my work to curious scholars from diverse disciplines. Their encouragement and support helped me turn two manuscripts into published non-fiction books. With that confidence boost, I am now a committed writer, despite the occupation being so far down the remuneration scale.

_______

Would you like to join ISAA? Would you like to attend ISAA’s national conference, The Lucky Country 50 years on to be held at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, Thursday, 9 and Friday, 10 October 2014? Contact: Administrative Officer: Meredith Hinchliffe or see https://www.isaa.org.au/

(2) ISAA website