‘Macedonians in Constantinople, drones over Gaba Tepe’, Honest History, 19 July 2016

Peter Stanley reviews Burak Turna’s The Hidden Victory of Anzacs: Gallipoli.

Imagine a world in which all historical sources, archival and published, on World War I have been destroyed, except for provincial newspapers in Australia and New Zealand and odd newspapers from the United States. How well could we interpret events in the Aegean and the Balkans in the early twentieth century? Not very well, you might think, since the North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times or the Wanganui Chronicle record more details of the price of fat hogget wethers in the spring sales or the prospects of the wheat yield than they do of the politics of the Ottoman Empire.

Still less would the Terang Express or the Maitland Weekly Mercury – you would think – provide a foundation for a confident, not to say radically revisionist account of not just the Ottoman Empire but the entire system of European international relations in the early twentieth century. The Turkish novelist Burak Turna has done just this, however, and the result is a bizarre fantasy but one presented as serious history.

Still less would the Terang Express or the Maitland Weekly Mercury – you would think – provide a foundation for a confident, not to say radically revisionist account of not just the Ottoman Empire but the entire system of European international relations in the early twentieth century. The Turkish novelist Burak Turna has done just this, however, and the result is a bizarre fantasy but one presented as serious history.

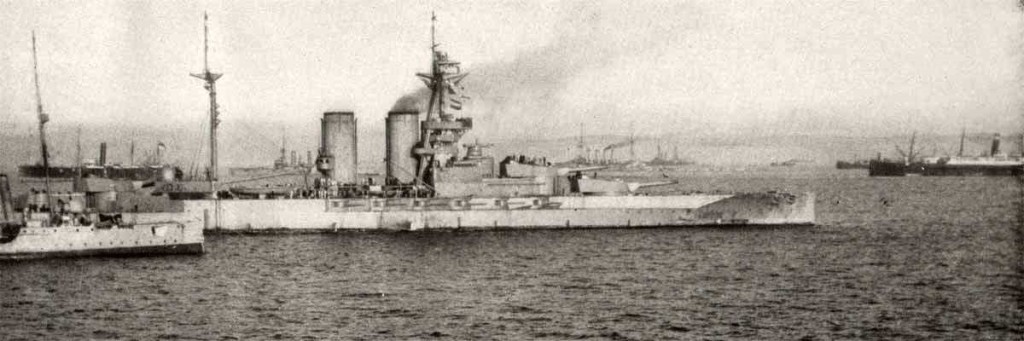

Turna’s The Hidden Victory of Anzacs: Gallipoli essentially contends that a rebel ‘Macedonian’ army seized power in Constantinople in 1909 and then acted in concert with Italian-directed ‘Garibaldian crusaders’ and the armies and navies of the European ‘Powers’ to conquer Turkey. In this process the crucial battle was for Gallipoli, a campaign fought in 1915, but in which the invading ‘Anzacs’ – the larger British force seems not to figure – were victorious. This victory was accomplished largely by the power of the British battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth and the employment of Marconi wireless equipment operating in ways that Turna doesn’t spell out very clearly but which appear to involve the use of reconnaissance drones and ‘network-centric warfare’.

Like me, you will almost certainly regard Gallipoli as a defeat for the invaders, Anzacs and others. ‘No,’ writes Turna, ‘Anzacs did not lose the Battle [of Gallipoli]; they won and handed Gallipoli to Garibaldians’ (p. 312).

Burak Turna is a novelist and author of hypothetical novels popular in Turkey. He has published the ‘Metal Storm’ series of novels which, his blurb tells us, has made him ‘the most critical and feared writer of Turkey’. Feared? Indeed: ‘historians carefully avoid to discuss with him on TV’. Whoa! Turna genuinely appears to believe that the essential truth, hitherto unknown, about the course of a European-Ottoman war can be discerned from the reports of European affairs published in Australasian provincial newspapers.

What is Turna claiming to be the ‘truth’ of Gallipoli? The book’s starting point is that the 1909 military coup that installed the ‘Committee of Union and Progress’ (CUP) in power in the Ottoman Empire did not actually occur, or not as it is conventionally understood. There was a coup (or rather the invasion and conquest of Constantinople) but the CUP was actually (Turna says) a front for a faction of the murky ‘Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization’, the militant wing of a (Christian) ‘state-like armed organization’ which, after seizing control ‘converted one arm of itself into Young Turks’ – becoming ‘a muslim [sic] nationalist organization’ (pp. 21-23).

Italy, Turna claims, led a coalition of forces of ‘the Powers’ – the nations of Europe – to invade what was left of the Ottoman Empire, gaining victory on Gallipoli. How? He claims that the invaders of Gallipoli possessed technical capabilities far beyond those we have till now understood, in ballistics, aviation, wireless telegraphy, target acquisition and weapons guidance. He believes, for example, that the Royal Navy’s ships were able to destroy targets on land guided by techniques of wireless telegraphy and guidance – techniques which he cannot actually describe.

Marconi with radio kit (Wikimedia Commons/Smithsonian Institution)

Marconi with radio kit (Wikimedia Commons/Smithsonian Institution)

Indeed, Turna seeks to prove that the ‘Anzac’ landing on Gallipoli was actually a great victory. He ignores the larger British force, though he claims that the French expeditionary force actually comprised ‘Garibaldian’ volunteers from a dozen countries and not metropolitan and colonial French troops. Italians (who do not figure in conventional accounts of Gallipoli at all) were centrally involved – Marconi wireless, don’t you see …?

It is hard to know where to begin to deconstruct this extraordinary fantasy – or, indeed, whether to bother at all. It could be written off as the product of an unschooled or undisciplined mind, one uninformed (and certainly unconstrained) by conventional historical methodology. But The Hidden Victory of Anzacs looks like a conventional book of history (except it lacks either references or a bibliography) and potential buyers need to be cautioned that, if they spend their £15.90 plus postage, they will be buying a book that is absolutely false in its assumptions, grossly flawed in its methodology and utterly misleading in its narrative, argument and conclusions.

Where, we might ask, is the evidence? Surely a century of scholarship has unearthed all the archival evidence we are ever likely to see? Ah, no, you see, because Burak Turna has a profound scepticism toward about what he calls ‘official history’. By this he means ‘the globally accepted information about our common past’ which is, he believes, so untruthful that he refers to none of it; not to official archives, not to the memoirs of participants, not to authoritative public accounts (such as The Times of London, also available digitally but unused); nothing except newspaper accounts published in distant places. These sources he describes as ‘meta datas … pure datas … free from comments and not prone to manipulation’ (p. 12).

Everything else, Turna says, is lies. His use of the term ‘meta-data’ is confusing. It is generally defined as ‘data that describes and gives information about other data’ – so, for example, a library catalogue describes the books in a library’s collection. How newspaper reports can be regarded as ‘meta-data’ eludes me; but perhaps it’s different in Turkish.

Turna deprecates – no, excoriates, dismisses and condemns – all previous accounts as ‘lies’, though without ever explaining what it is that he finds objectionable about all previous writing in several languages about Gallipoli. In his world, ‘official history’ encompasses everything that has previously been published about Turkey’s history from 1909 and on the Dardanelles-Çanakkale campaign. What he accepts, on the other hand, are newspaper reports; moreover, reports he has found by the magic of the internet and the digitisation of newspapers in several English-speaking countries.

Turna has accepted these accounts, though he is unaware or uncaring that they were written by journalists distant from the scene of the events in question, based on cables or official communiqués, most of which had been censored by the British military authorities. He also takes as incontrovertible, accounts foreshadowing events (such as the bombardment of the Dardanelles forts) as ‘proof’ that the events developed as had been foreshadowed.

The problem with this approach is that the newspaper reports that Turna draws on exclusively also support what he regards as the ‘lying’ official version. Newspaper stories published in Australia and New Zealand reflected and supported the ‘official’ version. Turna has found odd snippets that support his idiosyncratic reading of the campaign (for example, by cherry-picking reports of Italian volunteers for ‘Garibaldi’-inspired units as constituting ‘proof’ that the campaign was largely conducted by Anzacs supported by ‘Garibaldians’ under Italian command). How can these newspaper sources be regarded as ‘pure meta-data’ when they can also be used to buttress a view utterly contrary to his?

Burak Turna (Twitter)

Burak Turna (Twitter)

One of the fundamental problems with Turna’s approach is that he has turned conventional historical research methodology on its head – and not, as they say, in a good way. Of course, all evidence is usable, but some forms of evidence are more usable than others. For example, if I wanted to establish what the battleship Queen Elizabeth contributed to the Gallipoli campaign, I would begin with what are regarded as authoritative published sources (notably various official histories) but would also try to find more recent studies of the campaign, the ship, naval warfare in the period, etc., to see if anyone had challenged or revised the views published over 80 years ago. I would, of course, check the bibliographies of all of these books and try to find primary sources, such as records created by the ship’s officers.

I would consult this archival evidence in the United Kingdom National Archives, the Imperial War Museum, the Royal Naval Museum and other archives, some of them available on-line, and would look for what we might call ‘corroborative’ records, such as Australian military records, or the diaries of men who saw the ship in action. If I were extremely diligent I might then check contemporary reports in provincial newspapers to see if they add anything. Turna has bypassed all of these sources except the least reliable or significant – though newspapers on the National Library of Australia’s Trove facility are the most easily found.

Using the least significant (but most easily consulted) evidence is like someone writing a scientific thesis on wildlife based on the appearance of animals in television car advertisements, or a constitutional history using snippets of conversation overheard on buses. They would pick up references to jaguars or gazelles, or comments on this or that politician, but their accounts would be utterly unreliable and probably irrelevant. And why would they bother, when they could study animals in the wild or politicians and political ideas through more authoritative sources?

A serious question that Turna fails to address or answer is how he reconciles his idiosyncratic account with the massive amount of official and private archives – again found in several countries – which underpins the so-called ‘official history’. It is not that all other historians agree with each other, but none of them agree with Turna.

Turna simply fails to explain how the huge amount of diplomatic, military and unofficial records – ambassadors’ reports, the archives of the British, German, Turkish, French, Australian and New Zealand armies and their navies, and the letters, diaries, memoirs and photograph albums, not to mention civilian government and private records, none of which support his interpretation – can be reconciled with his version. Are we to infer that this archival lode has been fabricated – by whom, at whose direction and, above all, why?

Turna’s starting point is that Macedonian renegades seized power in Constantinople in 1909. Even if that were true, how is it possible for their agents to have infiltrated the archives of a dozen countries to fabricate evidence that would conceal the ‘real’ course of events in European Turkey in these years? It occurs to me that it is possible that Turna actually has no idea that such sources even exist.

In short, Turna’s account exceeds the bounds of credulity and must be dismissed as a pathetic invention. Sadly, he seems to have fallen victim to his own invention and has foisted on us a book purporting to be an historical account but which is in fact a fantasy.

HMS Queen Elizabeth at the Dardanelles, 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/Colliers)

HMS Queen Elizabeth at the Dardanelles, 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/Colliers)

I understand that, thanks to the magic of social media, Burak Turna is aware that this review is to appear. (I posted a sentence from it as a review on the Amazon UK site, which Turna saw and, in a message to Honest History’s secretary, sought a right of reply.) I am happy for Turna to reply. Indeed, I would be grateful if he were to answer several questions:

- On what evidence does he contend that ‘Macedonians’ conquered the Ottoman Empire in 1909 and that an Italian-led international force of ‘Garibaldians’ mounted the invasion of Gallipoli?

- Why has he not consulted any contemporary evidence except newspaper reports? Is he aware of the massive quantities of archival evidence available?

- How does he explain the degree of effort required to falsify the archival and published evidence that disagrees with his version of the campaign?

- How does he explain the huge discrepancy between his view and all other published accounts of the Gallipoli campaign?

- Why does he regard everything else published on this subject as ‘lies’?

It is possible that this book is, as we say in Australia, a ‘leg-pull’ – a joke, that the entire venture is a hoax. I think though that, sadly, Burak Turna is serious – and seriously deluded.

Peter Stanley is the President of Honest History and a research professor at the University of New South Wales, Canberra. He has published more than 30 books on military and social history and visited Gallipoli many times.