‘Lest we forget Lest We Forget: Rudyard Kipling’s “Recessional”: Honest History document’, Honest History, 2 May 2017 updated

Update 4 June 2017: an Army musician sang ‘Recessional’ at the opening of the Boer War memorial in Canberra last week.

Last week’s storm in a teacup about the Facebook post by Yassmin Abdel-Magied (otherwise known as ‘the hardy perennial annual Anzac Day beat-up’) left one question unanswered – or more likely unasked: where did those words, ‘Lest We Forget’ come from? We (or some of us) have become so used to hearing them or saying them – like ‘Happy Christmas’ or ‘Happy Birthday’ or ‘God Bless You’ – that we perhaps have lost track of what they are supposed to mean – somewhere between ‘May we not forget’ (those who died in our wars) and ‘Don’t you dare forget!’ maybe? – and many of us have certainly forgotten where the words come from, if we ever knew.

Those of us of a certain age, however – and perhaps even some Millenials and younger – will remember sonorous renderings of these words in a song sung at Anzac Day services, usually towards the end, somewhere after another standard (now forgotten?), ‘Land of Mine‘, but prior to the National Anthem – in those days, ‘God Save the Queen’ – which saw us all out and back to class. (Someone collected the hymn sheets for next time.)

The song – hymn really – is ‘Recessional‘; it was written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 and the author of the words was Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936).

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

The tumult and the shouting dies;

The Captains and the Kings depart:

Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice,

An humble and a contrite heart.

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

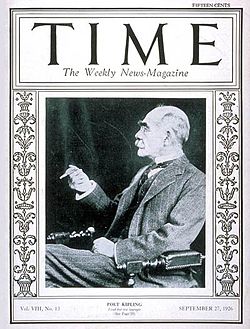

Kipling on the cover of Time, 27 September 1926 (Wikipedia)

Kipling on the cover of Time, 27 September 1926 (Wikipedia)

‘Recessional’ actually means ‘something you sing on the way out’. The usual tune for singing it used to be ‘Melita’ by JB Dykes, which is also the tune for the hymn ‘Eternal Father, Strong to Save’, often known as ‘The Sailors’ Hymn’, but many other tunes have been used. We looked in vain for a video of a decent choir singing ‘Recessional’ with Kipling’s original words to Dykes’ tune.

Three reasonably learned articles touching on ‘Lest We Forget’ are a note on JR Benjamin’s blog, The Bully Pulpit, another on an apparently anonymous blog called Impractical Criticism, and a piece by Howard Manns in The Conversation, which picks up the likely Biblical basis of the words: ‘Then beware lest thou forget the LORD, which brought thee forth out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage’: Deuteronomy 6:12, King James Version. The New International Version of the Bible has ‘be careful that you do not forget the LORD’.

Analysis of the song tends to attribute it to Kipling’s wariness about British imperialism – and awareness of the weight of ‘the White Man’s Burden’; it is not particularly about war. Kipling would probably have been surprised about how his words have come to be used, particularly in Australia, in a commemorative context.

To the extent that there are martial tones in the words of ‘Recessional’, Kipling may have had a different attitude to war after his son John was killed at the age of 18 at the Battle of Loos in 1915. Rudyard Kipling worked with the Imperial War Graves Commission after the war and composed the epitaph ‘Known Unto God’ for unidentified dead and the words ‘The Glorious Dead’ for the Cenotaph in London.

For those who might like to explore further, there are a couple of Kipling biographies linked to the Benjamin blog above. Don’t you dare forget!

2 May 2017