I have been interested in the American Civil War from the age of eleven. Over the years the idea grew that it would be worth attending in July 2013 the 150th anniversary of the war’s greatest battle at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The three-day battle resulted in a decisive defeat for Robert Lee’s Confederates at a total cost of 45 000 dead and wounded. The battlefield later became the site of Abraham Lincoln’s famous address, making the place a shrine to the Union cause rather than simply a site of slaughter. (What visitors from the South think of this appropriation is unclear; but their focus seems to be on the various Confederate state memorials on the battlefield itself, though the vast majority of the battlefield’s thousand or more memorials are indeed Union.)

Re-enactors, Gettysburg, July 2013 (photo: Peter Stanley)

In an attempt to penetrate the reality of the battle and to understand from within the phenomenon of historical re-enacting, I chose to spend the anniversary among the huge number of re-enactors who camp outside the town re-creating episodes from it. To do this I got myself affiliated to a Union re-enactment unit and paid my dues. Wanting to observe rather than to shoulder a weapon, I enterprisingly turned up in the uniform of an officer of the British army – an inconspicuous blue tunic and lavender trousers – which blended in with Union re-enactors. I had planned to spend three days mingling with them, learning about what motivated their expensive and time-consuming hobby and perhaps gaining insights into what re-enacting contributed to historical understanding.

In an attempt to penetrate the reality of the battle and to understand from within the phenomenon of historical re-enacting, I chose to spend the anniversary among the huge number of re-enactors who camp outside the town re-creating episodes from it. To do this I got myself affiliated to a Union re-enactment unit and paid my dues. Wanting to observe rather than to shoulder a weapon, I enterprisingly turned up in the uniform of an officer of the British army – an inconspicuous blue tunic and lavender trousers – which blended in with Union re-enactors. I had planned to spend three days mingling with them, learning about what motivated their expensive and time-consuming hobby and perhaps gaining insights into what re-enacting contributed to historical understanding.

This turned out to be one of the more spectacular errors of my professional life as an historian. Re-enacting and I were destined to not get on. I did form profound insights into the experience of mid-nineteenth century campaigning in general and this battle in particular. The weather, for example, was much as it had been in 1863, with 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) heat and humidity to match. It was so hot that Confederate re-enactors failed to show up to one scheduled fight because their supply of iced water had not arrived. But overall, despite the hospitality of my American hosts, who generously shared both their rations and their experiences of re-enacting going back thirty years, I found that the practice simply failed to gell: there was, as re-enactors say, no ‘period rush’.

I found that the highly orchestrated and regulated evolutions of re-enacting little resembled battle as I had understood it. Performing before bleachers filled with tens of thousands of pop-corn and hot-dog munching spectators, artillery and infantry occupied separate fields (for safety), while the infantry fired not at their opponents’ legs but in fact over their heads. No-one ran away; hardly anyone fell over; no-one screamed in pain. The only resemblance to the real thing lay in the confusion that bedeviled even supposedly rehearsed action. Standing beside a ‘regiment’ ‘firing’ at the ‘enemy’ a couple of hundred metres away failed to inspire in me any feelings of terror or indeed even mild anxiety: I knew I was safe from everything besides heat-stroke. Disappointed with my experience of re-enacting, I deserted the field (one of my few authentic actions) and sought refuge in Gettysburg’s new, air-conditioned museums.

Gettysburg had acquired three new museums since I last visited in 2006. They include the huge new museum at the National Battlefield Park visitors’ center (when in Rome …) which offers a minute-by-minute analysis of the battle showcase-by-numbing-showcase but also a detailed and subtle (and mostly ignored) analysis of the war’s causes. This institution manifests the American museum’s dedication to earnest didacticism, the display of unending ‘artifacts’ (including cases of, for example, every state button and a display of a dozen Union trumpets) but also a willingness to make bold and (to Australian sensibilities, often mawkish) patriotic statements.

Gettysburg Lutheran Seminary on Seminary Ridge, the key Confederate position, opened an impressive new museum in July. It displays life-size set pieces portraying the seminary before the war and its use as a hospital during and after the battle. This museum is notable for tackling the issue of slavery (and the arguments for and against it by, among others, those educated at the seminary) and for combining displays about the wounded treated in the seminary with assertions about the war’s higher purpose.

Finally, the David Willis House, in which Lincoln stayed before delivering his celebrated address, has been turned into a fine museum of the town, the battle’s effects on it and the writing of the address itself. In all three museums (adopting the broad American use of that word) the Gettysburg Address is prominent.

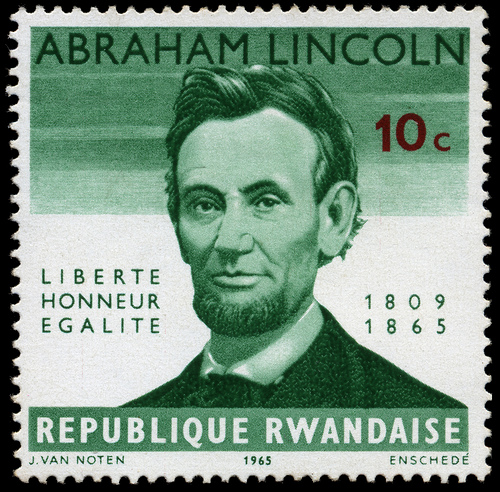

Die Briefmarke aus Ruanda aus dem Jahr 1965 hat als Motiv Abraham Lincoln (1809-1965), den 16. Präsidenten der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika (A Rwandan stamp from 1965 portraying Abraham Lincoln (1809-1965), the 16th President of the United States of America (source: Flickr Commons; photo: Bernd Kirschner)

Lincoln’s words, visible all over the town, on postcards and tea-towels, spoken by Lincoln impersonators and even adorning the balustrades of a motel, impart a nobility of purpose to what is not just any battlefield. These words not only gave the Union one of its most eloquent rallying cries but also in retrospect allow us to believe that the slaughter had a purpose, that the survival of the United States as a political entity and as the embodiment of an ideal of freedom was worth the cost. Nations seem to be better at formulating purposes for wars after the battles have been fought.

For this military historian Gettysburg became more than the dramatic battle that had captured my imagination as an eleven-year-old. While re-enacting proved, for me, an illusory route to understanding, Gettysburg’s museums harnessed what happened in the battle to the victors’ higher purpose, making the visit worthwhile, though not in ways I had expected.

History tourists, Gettysburg, July 2013 (photo: Peter Stanley)

Gettysburg, July 2013 (photo: Peter Stanley)