When a popular tourist information website took the Honest History name in vain, it deserved a closer look. There, on Trip Advisor, an American ex-pat in Germany was ‘amazed’ at how ‘blunt and honest’ about ‘triumphs and failures’ the Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum, 2 Unter den Linden, Berlin) was, compared with American museums. The headline on the piece, sucked up by Google’s algorithm, was ‘Honest history’. So the Museum was a must-see, coincidentally on the 72nd anniversary of Pearl Harbor.

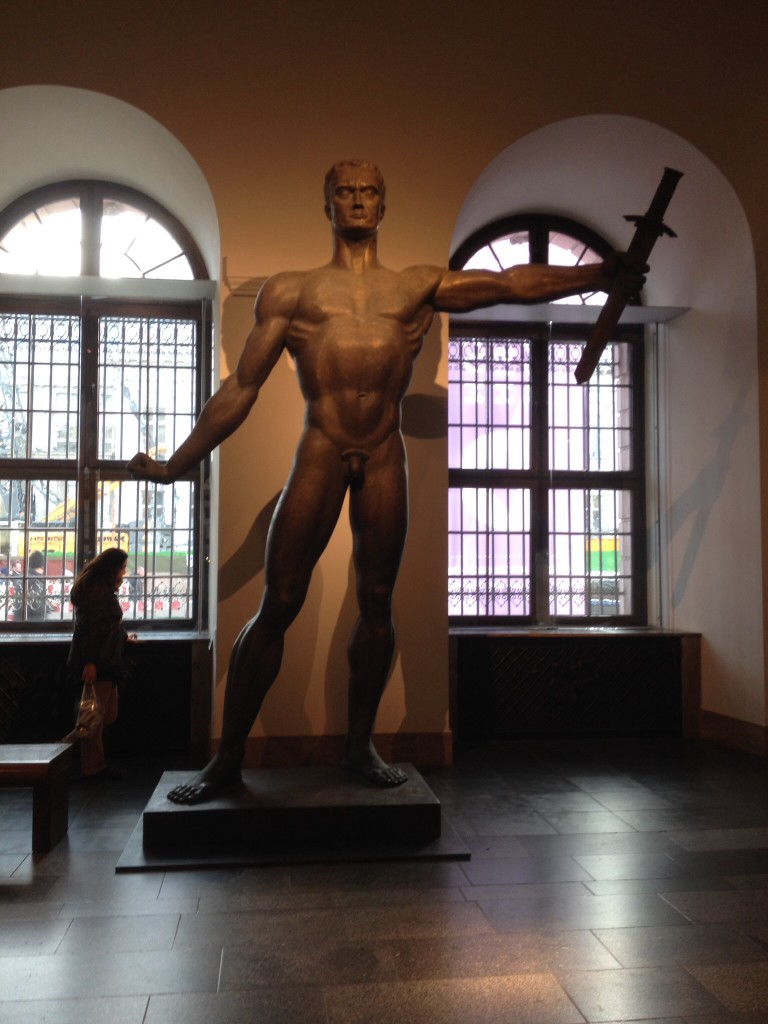

The tone of the Museum is set in the foyer, where there is a huge bronze of Lenin, cloth-capped, paunchy and avuncular, alongside a naked figure from 1938 representing the Wehrmacht. The latter is grim-visaged, muscular and wields a sword (by the blade). Both figures stand for a piece of German history: Germany in the old DDR as fellow-traveller with a doomed ideology; Germany 1933-45 as dupe of a mad visionary.

The Museum’s honesty derives first of all from the thoroughness of the coverage, from spirits in the woods two thousand years ago to guest workers at the turn of the current century. Themes are pulled out of the chronology and dealt with straightforwardly, laying out the evidence in pictures, sounds and artefacts and discussing it in spare and sober prose in German and English.

Jauncey looked mainly at the exhibits from Bismarck to post-World War II and saw how Kaiser Wilhelm II’s yearning to be another Frederick the Great combined with social unrest, nationalism and economic growth to produce ‘a climate in society in which peace was increasingly felt as a burden’. The ’causes of World War I’ industry would certainly go into much more detail than this but the quick summary chosen by the curator is not particularly flattering to the Germans of 1914.

The Museum’s treatment of World War I gives extensive coverage not only to military events but also to the home front, war bonds, strikes, economic hardship, hunger, peace agitation and ultimately near-revolution. Then the coverage moves on to the uneasy 1920s, the collapse of 1929 and the rise of Hitler.

The [National Socialist] regime’s claim to totality expressed itself in a constantly growing control over private life. Attitudes and behaviours that deviated from the regime’s norms were criticized at all levels of society. There was widespread fear of being denounced to the Gestapo, which often happened.

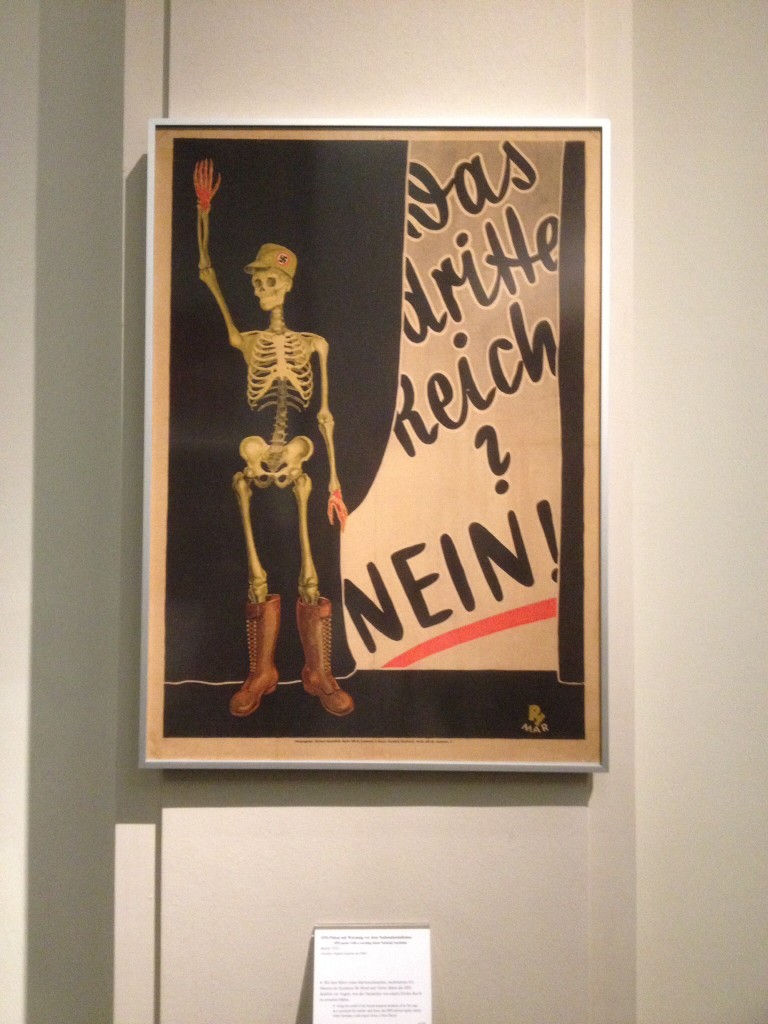

Facsimile of Democratic Socialist Party poster, Berlin, 1932, warning of the dangers of Nazism.

Facsimile of Democratic Socialist Party poster, Berlin, 1932, warning of the dangers of Nazism.

The honesty extends to the coverage of the Holocaust. There is a detailed model of the gas ovens at Auschwitz with queues of tiny plaster people waiting to be gassed. The obscene statistics of Auschwitz are spelled out: 900 000 Jews went straight from the Auschwitz railway station ramp to the gas chambers; tens of thousands of others, as well as Polish Gypsies and Russian POWs, died from overwork, hunger, disease or medical experiments; of the more than 1.3 million people who went to Auschwitz, only around 230 000 survived.

On the other hand, the Museum also captures the despair felt by many ordinary Germans as their country collapsed.

Many Germans took their lives in the last days of the war, since the final victory, trumpeted in the propaganda up to the very end, failed to appear and they were too deeply entwined in the Nazi crimes.

The honesty continues at the separate Jewish Museum, especially in its basement section on the Holocaust. Simple exhibits, mostly donated letters and photographs, tell in matter-of-fact terms the stories of German Jews uprooted from their lives to either migrate to escape the Nazis or be rounded up and taken to concentration camps, where most of them were ‘murdered’. (This word, rather than the vague ‘died’, is used deliberately to sheet home responsibility.) On the day we visited, Germans and foreign tourists alike confronted this part of German war history in a way that few of us confront our own Australian genocide.

Modern Berlin: protesters and tourists at the Brandenburg Gate, December 2013

Modern Berlin: protesters and tourists at the Brandenburg Gate, December 2013

There is a lot more, of course, to the history of Germany than the two World Wars and a lot more to Germany than how it has dealt with them. On our first evening in Berlin, I glanced out of the apartment window just in time to see, trotting past, a stray dog, decent-sized but of mixed ancestry. This animal looked cheerful enough and was clearly on a mission of some sort, although his progress towards it was a little erratic due to the fact that he was missing his near foreleg.

A happy, three-legged dog, ambling by himself down a badly-lit, graffitied Oderberger Strasse as Winter began to set in. A cleverer columnist than Jauncey might make a neat analogy between this slightly out-of-whack canine and the Germany of 2013. Jauncey would prefer to go back to the exhibits at the German Historical Museum and the Jewish Museum and suggest that losers ultimately benefit by having to confront all of their history while winners lose out by being able to get away with mythology. Victory has its drawbacks.

There should certainly be a lot more to commemorating war than gratitude for the deeds of men in uniform. Extending the well-worn words ‘Lest We Forget’ to apply to the victims of Auschwitz would be a good start.

The Australian War Memorial in 2016 opened a permanent exhibition on the Holocaust:https://honesthistory.net.au/wp/stanley-peter-review-of-the-holocaust-witnesses-and-survivors-at-the-australian-war-memorial/