Aden Knaap

‘Family matters: internationalism in early 20th century Australia’, Honest History, 2 December 2014

In mid-November this year Tony Abbott convened a Joint Sitting of Federal Parliament to welcome British Prime Minister David Cameron to Australia. The Australian Prime Minister’s speech, which blended Anglophilia with Christian religiosity, was signature Abbott. He gave thanks for the many gifts Britain had bestowed upon humanity: parliamentary democracy; the Common Law; constitutional monarchy; the English language: Shakespeare; the Beatles; Wilberforce; the first Industrial Revolution; Churchill. He flinched at the thought of an Australia deprived of British colonisation (‘And what would this world be if Britain had not settled the territory that Captain Cook earlier called New South Wales?’). He acknowledged Australia’s location in the Asia-Pacific but insisted on the continued importance of the nation’s ancestral ties to Britain. ‘Australians [have] ceased to regard Britain as the mother country’, Abbott conceded, ‘but we’re still family’.

The idea of a longstanding sense of kinship between Britain and Australia is hardly controversial. Several historians – Neville Meaney, James Curran and Stuart Ward, among others – have argued persuasively that Australian nationalism was grounded in a particular conception of Britishness, at least until the 1970s. What is contentious is the extent to which this sense of Australian Britishness was all-encompassing. In recent years scholars have complicated the narrative of Australian nationhood, teasing out the ways in which some 20th century Australians (most notably, pioneering politicians and feminists) understood their place within a more extensive international world. This is a rich new literature (for example, Campo and Lake, Lake and Paisley). But, in isolating a small group of internationalists, it confines internationalism to the margins of Australian history.

SM Bruce presiding over the League of Nations Council, Geneva, 1936 (Wikimedia Commons/National Archives of Australia)

SM Bruce presiding over the League of Nations Council, Geneva, 1936 (Wikimedia Commons/National Archives of Australia)

In particular the vitality of the League of Nations movement in Australia forces us to reconsider the place of internationalism in early 20th century Australia. Australians were, of course, not the only ones to form popular associations in support of the League. During and after World War I national League societies sprang up across the Anglo-European world and beyond. A British League of Nations Society emerged as early as May 1915 and its successor, the League of Nations Union, quickly established itself as the largest and most vocal of the national League groups.

Compared with their counterparts in Britain the beginnings of the Australian League movement were somewhat belated. Nonetheless, by 1923, local League of Nations Unions had been established in all six states. Through an impressive array of promotional and educational initiatives the League’s advocates in Australia sought to inculcate an international consciousness in the Australian mind. In doing so they recast what it meant to be Australian: to be a citizen of a newly federated nation, an outpost of the British Empire and a member of this new international community, the League. The Australian ‘family’ was more expansive than Abbott allows.

The League movement in Australia never enjoyed as widespread a following as the League of Nations Union in Britain. Over the course of the 1920s the network of League of Nations Union offices in the United Kingdom rapidly proliferated; its headquarters remained in London but local branches spread throughout the British Isles. By 1931 League enthusiasts had founded a total of 3036 local branches. As the movement expanded, membership ballooned, rising from 60 000 individual members in 1920 to a peak of more than 400 000 by 1931.

In Australia power remained centralised in the state capitals with just a few scattered sub-branches operating in suburban centres and country towns. Membership was restricted and fluctuated considerably. No Australian branch ever amassed more than 5000 members and those of the smaller states in particular – Western Australia, Tasmania and to a lesser extent Queensland – maintained meagre figures for much of their lifespan.

Despite limited membership League of Nations Unions achieved a remarkable level of mainstream legitimacy in Australia. Much of the movement’s authority came from the elite men and women that staffed the governing committees. The composition of the movement’s leadership differed across the various state branches. In Sydney businessmen dominated the New South Wales executive to a far greater extent than in other states, for example.

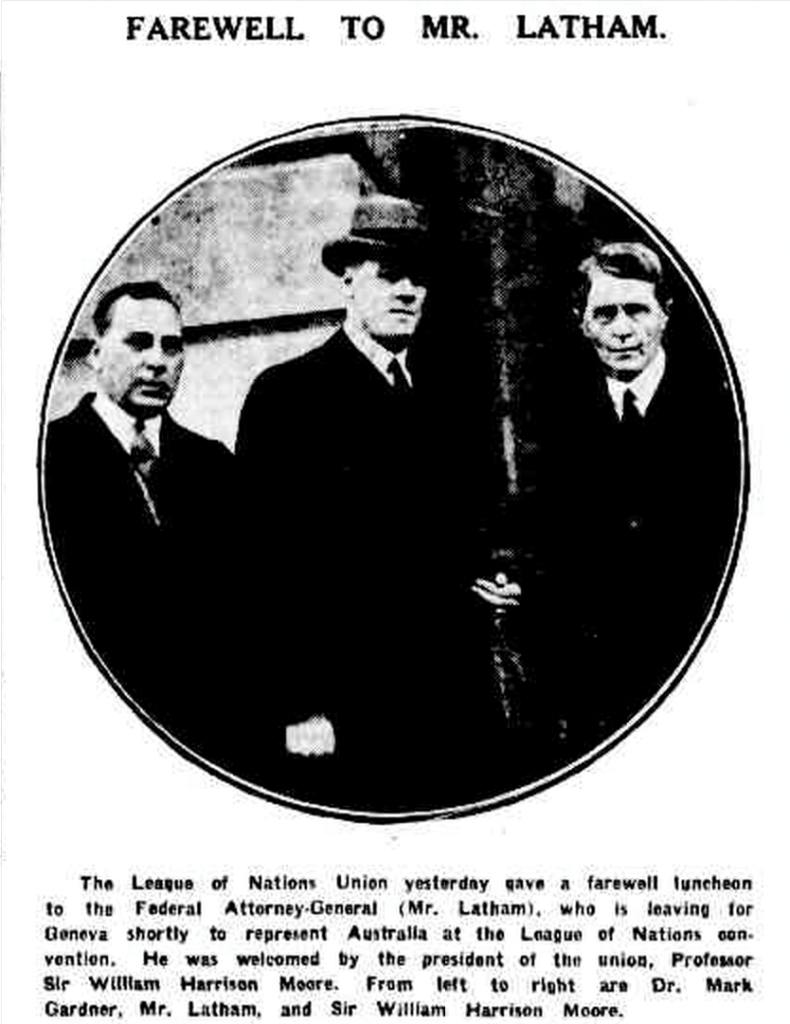

Members of the Victorian League of Nations Union: Mark Gardner, John Latham and Sir William Harrison Moore (NLA Trove/Argus, 28 July 1926)

Members of the Victorian League of Nations Union: Mark Gardner, John Latham and Sir William Harrison Moore (NLA Trove/Argus, 28 July 1926)

Generally, however, the leadership attracted well-educated members of Australia’s middle and upper class: politicians, academics, clergymen and commercial leaders. Some of the country’s foremost politicians and intellectuals were active members: future prime ministers Joseph Lyons and Stanley Bruce served on the executives of the New South Wales and Victorian branches; John Latham, future attorney-general and chief justice of the High Court, was founding president of the Victorian League of Nations Union; HV Evatt, later president of the United Nations General Assembly, was vice-president of the New South Wales branch; while renowned academics William Harrison Moore, Hessel Duncan Hall and Keith Hancock were all energetic members.

In political terms the leadership attracted individuals from across the political spectrum but members tended to be centrists capable of forging strong cross-party relationships. This claim to political centrism allowed League of Nations Unions to form close relationships with successive state and federal governments: supportive members of parliament frequently joined as members or spoke at organised gatherings, government treasuries provided financial assistance and members were regularly appointed as Australia’s delegates to League assemblies.

The activities of League associations in Australia were diverse but can be divided into three main categories: promotion, education and government lobbying. At least initially the highest priority for most branches was publicity. League of Nations Union headquarters in all six states embarked on aggressive propaganda campaigns, circulating pamphlets lauding the League, showing League films and pontificating on the League via broadcast radio.

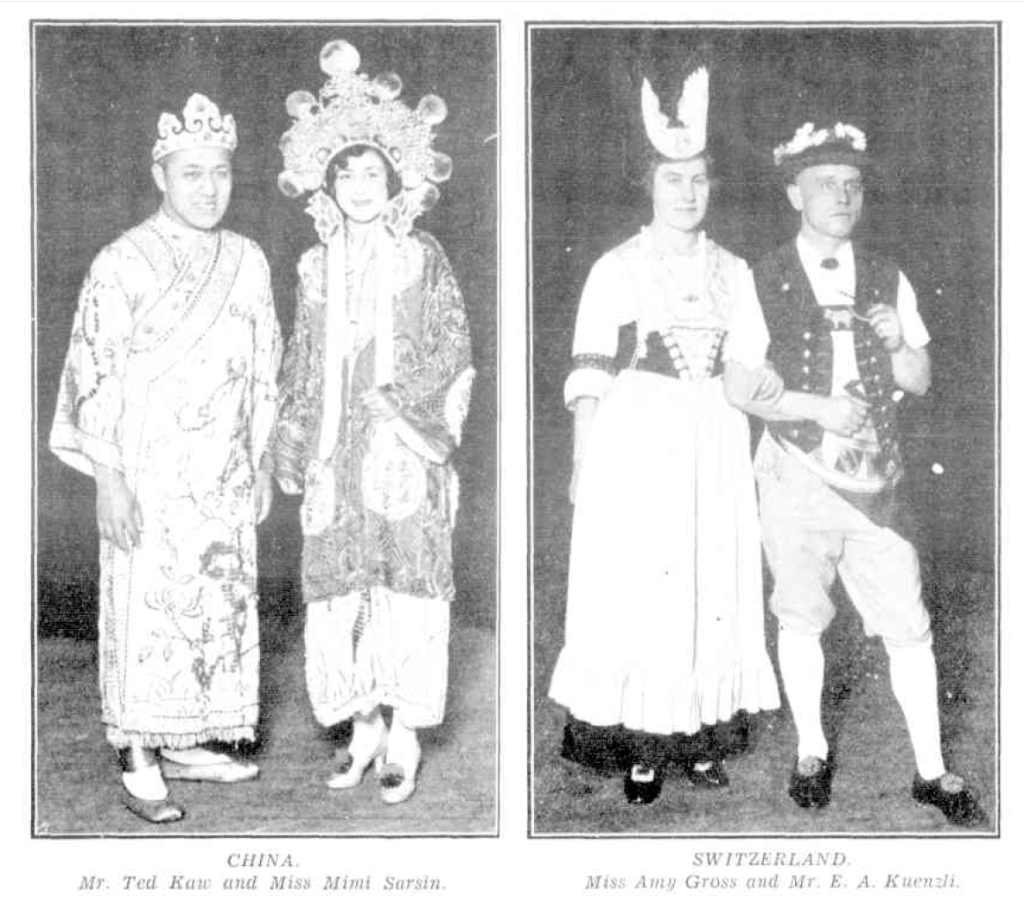

An annual International Ball formed the pinnacle of the social calendar for several state branches. The Balls were partly fundraising events but they also offered a chance for prominent local citizens, including vice-regal, governmental and consular representatives, to mingle with League enthusiasts while observing spectacles of pageantry and national performances. According to one observer the International Ball organised by the Newcastle sub-branch offered ‘a wonderful lesson of how the League of Nations is banding the peoples of the world together in the cause of peace’.

International Ball, New South Wales League of Nations Union, Sydney, September 1930 (NLA Trove/Sydney Mail 10 September 1930)

International Ball, New South Wales League of Nations Union, Sydney, September 1930 (NLA Trove/Sydney Mail 10 September 1930)

More than simply spreading awareness of the League movement in Australia, League of Nations Unions undertook comprehensive educational campaigns designed to stoke interest in the League. Branches throughout Australia set up libraries for public use, arranged study groups and debates on international affairs, sponsored analyses of Australia’s international obligations, and hosted conferences and lectures at which members and experts trumpeted the latest efforts of the League. These educational initiatives were extensive, consuming most of the movement’s resources. In 1935, for instance, the New South Wales branch claimed that local members had given over 2000 lectures in the Sydney metropolitan area alone. League supporters also targeted Australian schools and universities, attempting to cultivate an internationalist spirit among students.

Members worked closely with state government education departments in planning the instruction of students on the League, the incorporation of the League into subject syllabuses and the distribution of pro-League literature to students. The Australian League movement was particularly successful in connecting with students. Pupils of primary and secondary schools paid a nominal fee to become junior members. The network of junior branches of the New South Wales branch was the most extensive: by 1937 it tallied more than 100 000 student members.

The leaders of the Australian League movement may have embraced a novel sense of League internationalism but they were far from radical ideologues; just the opposite. Members characteristically maintained strong connections with Britain. State branches were stacked with ardent imperialists and distinguished émigrés from Britain. In Victoria and New South Wales, for instance, the founding membership of the movement overlapped considerably with that of the Round Table, an imperial-minded group that promoted closer ties within the Empire.

The imperial leanings of the Australian League movement also manifested themselves at an institutional level. Absent a clear hierarchy within the Australian League movement, state branches often looked to London for guidance. Australian internationalists, then, easily accommodated Empire in their conceptions of the League.

Paying tribute to David Cameron, Abbott offered up a simplified account of the Australian past: ‘Modern Australia has an Aboriginal heritage, a British foundation and a multicultural character’, he proclaimed. Given the audience, and the imperative of political expediency, it is unsurprising that the Prime Minister chose to ignore the internationalism of 20th century Australia. History does not have the same excuse.

Aden Knaap is an associate of ‘Inventing the International’, a Laureate Research Program in International History based at the University of Sydney. The author wishes to thank Professor Glenda Sluga for supervising the thesis upon which this article is based. All correspondence to Aden Knaap: aden.david.knaap@gmail.com.