Douglas Hynd*

‘The global, cultural and theological Bible: uncovering a history’, Honest History, 12 June 2018

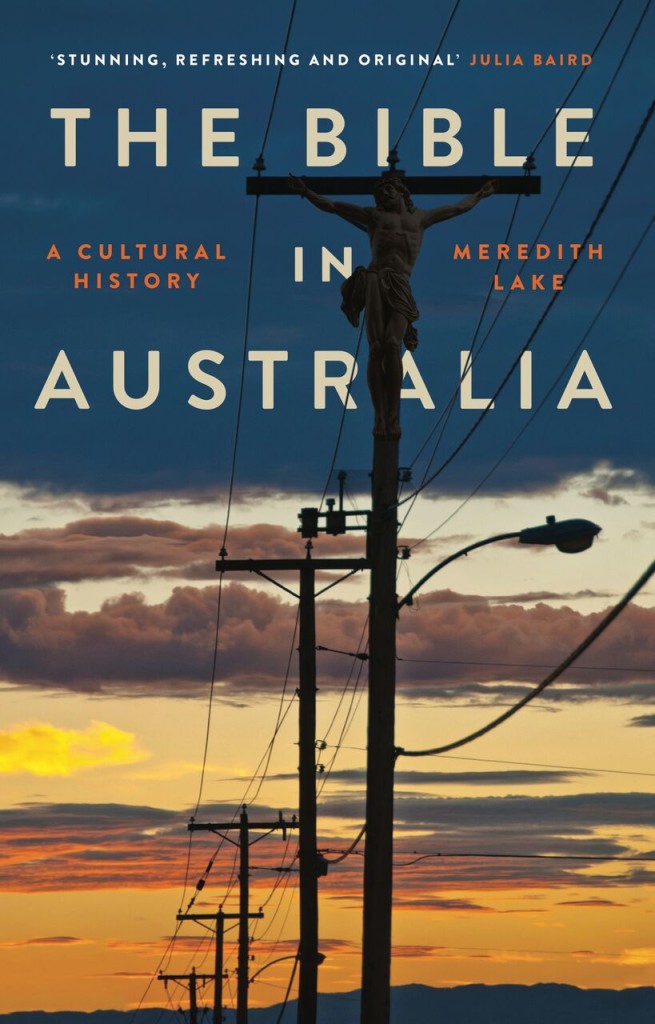

Douglas Hynd reviews The Bible in Australia: A Cultural History by Meredith Lake

You might think a history of the Bible in Australian culture wasn’t a topic that would generate media attention. How wrong could you be?

Meredith Lake’s recently published historical exploration of the impact of the Bible on Australian culture is attracting interviews on radio, events in inner city bookshops well outside the Bible belt, and enthusiastic reviews in the weekend papers. Andrew West on Radio National, Michael McGirr in Fairfax, Andrew West again with an audience at Gleebooks offer but a sample of the response.

Meredith Lake’s recently published historical exploration of the impact of the Bible on Australian culture is attracting interviews on radio, events in inner city bookshops well outside the Bible belt, and enthusiastic reviews in the weekend papers. Andrew West on Radio National, Michael McGirr in Fairfax, Andrew West again with an audience at Gleebooks offer but a sample of the response.

Koby Abberton emerges like a shark onto the sand at Maroubra Beach. Tattooed from shoulder to shoulder, his body bears letters like teeth: “My brother’s keeper”. The phrase proclaims Abberton’s fierce loyalty to the Bra Boys, the infamous surfer tribe he leads. It defines the us-and-them mentality he and his Maroubra crew have forged in confrontation with “outsiders” and in defiance of the police.

“My brother’s keeper” comes from the Bible. In the book of Genesis, Chapter four, Cain attempts to dodge responsibility for his murdered sibling Abel by asking God “Am I my brother’s keeper?” The question sums up Cain’s murderous disregard for his brother’s life. The Bra Boys have turned the old meaning of the phrase upside down (p. 1).

These opening paragraphs suggest why Lake’s book has attracted this interest. She has a sharp eye for an engaging story, an ability to tell it economically, yet with rich detail, while making unexpected connections. Lake conveys a genuine warmth in her accounts of the wide cast of characters that make an appearance. Her writing is characterised by what came across to me as a humanism of respect for her subjects and a willingness to reach for a shared understanding, no matter how strange these folk may appear to many 21st century readers.

Lake is comfortable with complexity and nuanced in her judgments. Behind this accessible historical narrative is substantial research evidenced in her 45 pages of endnote documentation, along with a ‘select’ bibliography that runs for five pages.

My only real criticism is minor and relates to the subtitle ‘A Cultural History’. This is to a degree misleading as the ground covered in the book includes, as well as the cultural impact of the Bible, a history of its impact on politics and society. In her overall assessment, Lake challenges two competing myths that are advanced – or at least implicitly assumed – by the respective protagonists in the contemporary culture wars.

One is that Australia since the convicts has been a doggedly secular society and culture. Another is that Australia is (or was, or should be) a straightforwardly Christian nation. The often-surprising history of the Bible here disrupts both assumptions. It enables a richer, more interesting and expansive story (p. 3).

In shaping her narrative Lake uses three major themes, the globalising Bible, the cultural Bible and the theological Bible. These themes are traced across four broad, though not tightly specified, chronological periods, the colonial era up to about 1850, the ‘Great Age of the Bible’ through to Federation, the first half of the 20th century, and the post-World War II era through to the present.

In this frame, the Bible’s career in Australia is in Lake’s view both interesting and complex. The Bible arrived as a core element in the colonial inheritance, as part of the British imperial project. It then took on dynamic and conflicting roles in the emerging Australian culture and remained a continuing element in the transformation of the Christian faith during the emergence of a more secular society.

But what is ‘the Bible’? The answer is not quite as simple as it may seem on first glance. From Lake’s perspective what is really interesting is that the Bible

does not really exist. Or rather that it does not exist in a static or self-evident way; the Bible is a fluid thing, ever-changing. In different times and places and among different communities, it has comprised different books, in different orders, in different translations and different editions … [A]t a truly astonishing rate in modernity it has changed and been changed by the proliferating forms, languages, contexts and communities in which it appears (pp. 3-4).

Lake’s historically informed awareness of these ‘shape-shifting’ characteristics of ‘the Bible’ gives her both the ability to identify the diversity of ways it has become part of the taken-for-granted texture of Australian life, and alertness to evidence of its usage by unlikely protagonists. Given the current association in much of the media of Christianity with conservative politics and social stances, it is interesting to note the stories that Lake tells of the role of scripture in the emergence of trade unions and the Labor Party, the campaigns for female suffrage and Indigenous rights.

These are interesting stories that deserve to be better known. They have lessons to teach us about the role of a range of social movements and institutions such as the churches in shaping Australia. In this connection, while Lake doesn’t neglect Anzac Day it falls into a wider historical narrative, rather than being at the centre.

The significant role of the Bible in both the Indigenous struggle for justice and the survival and recovery of Indigenous languages is not well known outside the Indigenous community. The life of William Cooper is a story of a struggle for justice for Indigenous people that lasted all Cooper’s life. In 1938 he led a group of Indigenous leaders in observing 26 January as a Day of Mourning. The theological Bible helped Cooper expose the failures of settler Australia, undermined the taken-for granted-imperialist and nationalist assumptions, and enabled Cooper to make a profound critique of colonialism. ‘At the same time he found in the Bible an affirmation of the inherent equality and dignity of Aboriginal people, of their right to fair treatment and of their ownership of the land as a God-given heritage (p. 277).’

Methodism is under-appreciated in the wider community. William Spence was a notable union organiser, associated with the founding of both the Amalgamated Miners Union and the Amalgamated Shearers Union. He was taught to read by his mother using the Bible, became active in the leadership of the local Presbyterian Church, and was later a lay preacher in the Primitive Methodists. His faith and politics were closely intertwined with the Bible as his point of reference. Indeed, during the 1890s knowledge of the gospels was assumed among Australian socialists, whether they were Christian or not.

The connections between the Bible, temperance and female suffrage are traced out by Lake in yet another story that runs against the grain of popular assumptions about Christianity as a bulwark of conservatism. The Bible was a resource and motivation for evangelical women in their reform agenda in the late 19th century, and for whom temperance and female suffrage were intertwined goals.

Bardon (Qld) Methodist Church Sunday School, 1947 (ChurchesAustralia)

Bardon (Qld) Methodist Church Sunday School, 1947 (ChurchesAustralia)

The Bible was not the sole possession of evangelical temperance advocates but these folk drew on it for their vision, which went well beyond making society more sober.

Many WCTU women … sought a world in which women as well as men shaped the laws of the land to secure a safer, purer and more just society. In the hands of women like Louisa Lawson, too, whose politics tended toward socialism and whose relationship to orthodox Christianity was complicated to say the least, the Bible could provide a language – a vision – for something like heaven on earth (p. 209).

In the closing chapters, Lake brings to our attention some of the more unlikely engagements between writers, musicians and the Bible. Why do Nick Cave and Helen Garner, for example, make an appearance here? Her intriguing account sketches some stories of the personal experiences of creative encounter by such cultural icons with the long religious and cultural trajectory of the Bible.

* Dr Douglas Hynd is Adjunct Research Fellow, Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture. Apart from this review and his recent reviews of The Fountain of Public Prosperity and Saints and Stirrers, he has written a number of articles for Honest History on the links between commemoration and religion. Use our Search engine.