‘The Australian War Memorial: a changed future’, Honest History, 2 June 2021

In August 1916, a tall, lean figure, dressed in the khaki of the Australian Imperial Force, strode through the battlefield of Pozières, in the Somme department in northern France, not long after the fighting had ceased. He was Charles Bean, the official Australian war correspondent. With him were two others – one a military chaplain, Walter Dexter, the second a young man, a lad really, Arthur Bazley, who was Bean’s assistant. They spent the summer night on the battlefield under the stars.[1]

28 August 1916. The main street of Pozières after heavy bombardment by the British and the Germans, looking towards Bapaume (ABC/AWM EZ0095)

In his role as the official war historian for Australia, Charles Bean had witnessed most of the recent battle which in the end had accounted for 23 000 Australian casualties, 6800 of whom had died in action or of their wounds. He was deeply moved by the carnage. On 4 August he wrote in his diary.

Pozières has been a terrible sight all day – steaming with pink and chestnut and coaly smoke. One knew that the brigades which went in last night were there today in that insatiable factory of ghastly wounds. The men are simply turned in there as into some ghastly giant mincing machine. They have to stay there while shell after huge shell descends with a shriek close beside them – each one an acute mental torture – each shrieking, tearing crash bringing a promise to each man – instantaneous – I will tear you into ghastly wounds – I will rend your flesh and pulp an arm or a leg – fling you, half a gaping quivering man like these that you see smashed around you, one by one, to lie there rotting and blackening like all the things you saw by the awful roadside, or in that sickening dust crater.[2]

It was here at the aftermath of Pozières, reflecting on the loss of Australian lives, that Charles Bean began to develop his vision of a national memorial.

The next year, while at the British headquarters in France, he wrote:

Every country after this war will have its war museums and galleries and its library of records rendered sacred by the millions of gallant precious lives laid down in their making. In London, Paris, Belgium, the war collections, and the war pictures, the war archives will be the goal of millions of visitors, and the centre of thousands of students as long as their peoples endure. Some day a magnificent collection in Australia will be the equal of them all, and will contain a war museum as interesting to visitors from Europe or America and to Australians themselves as, are the great London collections with their relics of Nelson and Wellington, the Crimea, the Mutiny and the Soudan, today.[3]

Sharing Bean’s vision was John Treloar. Treloar had been a public servant in the Commonwealth Department of Defence before enlisting in the 1st Division, AIF. He served as a Staff Sergeant at Gallipoli before being evacuated back to Australia with enteric fever. On recovery, he reenlisted in No 1 Squadron of the Australian Flying Corps as a lieutenant (equipment officer) and served in Egypt and France.

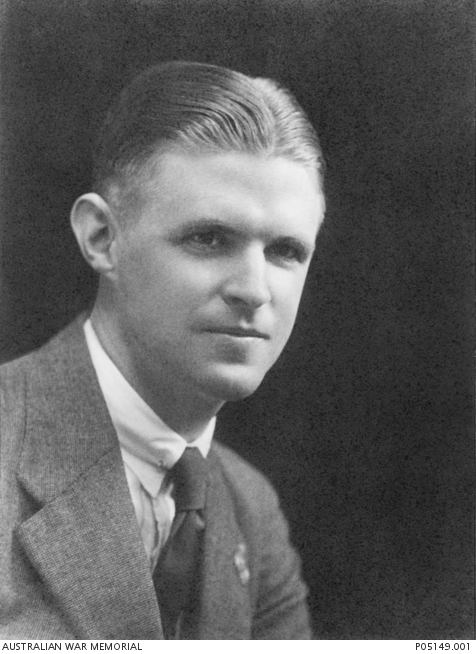

John Treloar c. 1922 (AWM P05149.001)

John Treloar c. 1922 (AWM P05149.001)

In May 1917, Treloar was selected to organise the newly formed Australian War Records Section. Although Treloar has been somewhat overshadowed by Charles Bean in the Australian War historiography, together they were the driving force for the eventual establishment of the Australian War Memorial. Treloar was to become the Memorial’s first and longest-serving Director from 1920 to 1952.[4]

I do not wish to go into the details of the formation of the War Memorial we know today other than to say Bean and Treloar had to face enormous difficulties and setbacks. At the end of the war, Australia had serious financial challenges to resolve, followed by a devastating influenza pandemic and then a world-wide depression. Bean and Treloar had difficulties in first gaining government approval for a national memorial and then in gaining the necessary funds to establish, maintain and develop it primarily as a memorial and as a museum. But they endured, and an incomplete memorial opened in 1941, during another world war, but was not completed until 1971.[5]

Today, the Australian War Memorial has become one of the most visited and important cultural institutions in the country. Many Australians have a deep respect for it and what it stands for particularly the veterans and their families and descendants of those who fought in conflicts. The experience these folk have during a visit is often emotionally moving and unforgettable.

The Memorial building and contents were placed on the Commonwealth Heritage List in 2004 and the National Heritage List in 2006. Established in 2003, the Commonwealth Heritage List is a register of places under the control of the Australian Government on land (and waters) directly owned by the Commonwealth, the people of Australia. The National Heritage List is Australia’s list of natural, historic, and Indigenous places of outstanding significance to the nation as a whole.

Part of the statement of the Memorial’s significance for the Commonwealth Heritage List reads:

The Australian War Memorial (AWM) is Australia’s National Shrine to those Australians who lost their lives and suffered as a result of war. As such it is important to the Australian community as a whole and has special associations with veterans and their families …

It goes on to state:

The AWM building is a purpose built repository reflecting the integral relationship between the building, commemorative spaces and the collections. This is unique in Australia and rare elsewhere in the world. The values are expressed in the fabric of the main building, the entrance, the Hall of Memory, the collections and the surrounding landscape.[6]

Now the Australian War Memorial is about to enter a new phase of its existence. A major redevelopment is being undertaken, backed by the Australian Government. The redevelopment entails major changes over seven years period at a cost of $498 million. According to the Memorial, the motivation is ‘to modernise and expand our galleries and buildings so we can tell the continuing story of Australia’s contemporary contribution to a better world, through the eyes of those who have served in modern conflicts, connecting the spirit of our past, present, and future for generations to come’.

Charles Bean with Prime Minister Hughes and Brigadier HA Goddard, Mont St Quentin, September 1918 (Inside Story/AWM)

To do this, the redevelopment is to provide space for the recent conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Solomon Islands and Timor Leste, and for conflicts to come. At present, only four per cent of the Memorial’s collection can be displayed. The changes will include a new southern entrance and a large exhibition space constructed at the rear of the building which will necessitate the demolition of Anzac Hall, which was completed just 20 years ago. Further landscape changes are also planned. Thankfully, the present Commemorative Area, Hall of Memory and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier will not be affected.[7]

The redevelopment proposals have come under strong professional and community opposition. Foremost among the objections are those from the Australian Heritage Council, the Australian government’s principal advisory body on heritage. The council reviewed the proposal under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act and advised strongly against it. In a carefully worded letter to the Memorial the Council concluded:

Regrettably, the Council cannot support the conclusion that the proposed redevelopment will not have a serious impact on the listed heritage values of the site and recommends that the [proposal] be given serious attention.[8]

Further objections to the redevelopment came via an open letter to the Prime Minister signed by over 70 notable Australians of broad professional backgrounds, many of whom were recipients of Australian honours and awards. The signatories included veterans, academics, historians, architects, former diplomats, former heads of Commonwealth agencies, heritage consultants and former staff of the Memorial.[9]

But perhaps the most telling criticism came from Brendon Kelson (not Nelson), former director of the Memorial (1990-1994), who stated in a submission to the Joint Parliamentary Standing Committee inquiry into National Cultural Institutions that:

This huge redevelopment would turn upside down the Australian War Memorial’s unique standing as the most revered memorial museum of its kind and among the world’s great national monuments.[10]

The ‘unique standing’ of the Memorial is that, first and foremost, its role is remembrance for those who have served in conflict and, secondly, as a museum of military history. It would seem (to me at least) that the management of the Memorial has lost sight of this remembrance role.

Now I would like to offer a challenge to those politicians and senior bureaucrats who will be making the final decisions on how this proposed redevelopment will turn out. I would like them to take some time out of their offices and stand out in front of Parliament House, our symbol of democracy, and look down over Federation Mall, across Lake Burley Griffin and up along the line of Anzac Parade to the stark but imposing form of the War Memorial building.

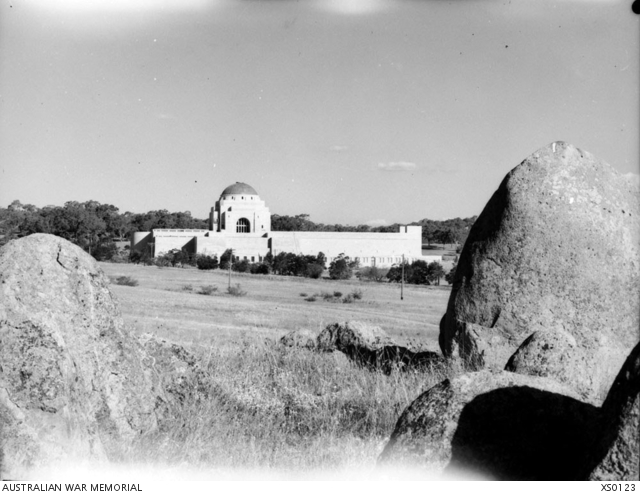

The Memorial, c. 1941: northern facade from slopes of Mount Ainslie (AWM XS0123)

The whole vista has been deliberately planned this way so that our political leaders can stand at the entrance of the Parliament building and reflect on the sacrifices that have been made by our service men and women before they enter Parliament House to go about the daily business. I challenge them to think hard and long about what they have just seen. Think about the debt that is owed by us all.

But I would like to offer our representatives a further, more personal challenge. Take some more time out of your offices and go to the Memorial itself. It is not far. While there cast your eyes and minds over the names inscribed in on the Roll of Honour and the sea of red poppies that have been placed next to the names by the people who have visited and who have deeply cared.

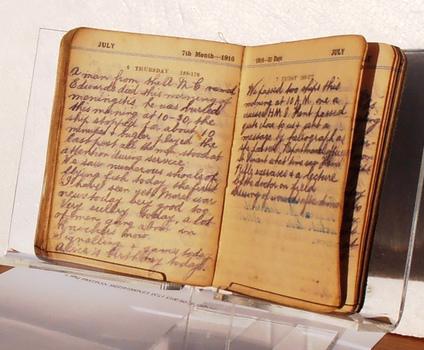

Now, I ask them to take some more time and go into the Memorial’s research centre. Ask at the desk to see one of the original letters or diaries that are stored there, written by men and women who have put their lives in danger. I would suggest a diary written during the Pozières campaign so you can perhaps get an inkling of what Charles Bean saw and felt. Ask for a hand-written original and not a transcript.

Now, sit down in a quiet place and carefully take the pages from the file cover and read about the experience of the writer. Perhaps you will notice that the diary entries or the letters are written in pencil with a shaky hand. Perhaps you will notice that the lettering becomes thicker as the tip of the precious pencil wears down and is reduced to an unwieldy stub. Perhaps you will notice grubby finger marks on the pages as the writer struggles with the mud or dust in his small dugout as the shells fall about, some too close for comfort.

Or perhaps there will be blotches on the page where the tears of a weary nurse have fallen while she writes exhausted but quietly after a long day caring for the wounded, desperately trying to save their lives. You may even come across a pressed and dried twig of rosemary or the petals of a red poppy wedged between the pages. Were they placed there by the young soldier writing about his experience, or was it the nurse who had found them and picked them with care? Or was it by a loving parent or relative who has received the diary and is now grieving for the writer who will never return?

Whatever the case, you will have now looked deep into the very heart and soul of what the present War Memorial represents, perhaps even the heart and soul of this country. The bricks and mortar making up the building structures and the exhibits located under the roof tell a part of the story, but the pages you have held in your hand hold the real meaning.

Then, put the pages back into the plastic cover, tie up the binding of the file and return it. But do not forget what you have seen and held in your hand. Do not forget who was writing the words and thoughts, where they were, what they did and what they had to endure. Now go back to your office and ponder your role in the coming planning and developments of the building. What are you doing? Do not stuff it up!

I wonder what Charles Bean and John Treloar would think of the redevelopment.

Diary 1916-17 of Private HN Derrick, Tallangatta Valley, Vic, 37th Battalion, died 12 November 1918 (Victorian Collections)

Diary 1916-17 of Private HN Derrick, Tallangatta Valley, Vic, 37th Battalion, died 12 November 1918 (Victorian Collections)

[1] Michael McKernan, Here is Their Spirit. A History of the Australian War Memorial 1917-1990 (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press in association with the Australian War Memorial, 1991) p. 30.

[2] Cited in Peter Burness (ed.), The Western Front Diaries of Charles Bean (Sydney: New South, 2018) p. 143.

[3] CEW Bean, The Capricornian (Rockhampton, Qld), 29 December 1917.

[4] Denis Winter, ‘Treloar, John Linton (1894–1952)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1990, accessed online 12 March 2021.

[5] Steve Gower, The Australian War Memorial. A Century on from the Vision (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2019) p. 6. Review.

[6] National Heritage List, ‘Australian War Memorial and the Memorial Parade, Anzac Pde, Campbell, ACT, Australia’, Australian Heritage Database, accessed 14 March 2021.

[7] Kate Midena & Peta Doherty, ‘Australian War Memorial proposed development of Anzac Hall slammed as “wasteful”’ “arrogant” and “objectionable”’, ABC News, 19 July 2020, accessed 31 May 2021.

[8] David Kemp, Chair, Australian Heritage Council, to Australian War Memorial Development Team, 31 July 2020.

[9] ‘Open letter to Prime Minister opposing $498m War Memorial redevelopment: reply (signed by Director, War Memorial) received’, Honest History, 14 November 2020, accessed 31 May 2021.

[10] Brendon Kelson, Submission 18, Parliament of Australia Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories, Inquiry into National Cultural Institutions, (2018-19).

* Peter Dowling holds a PhD in archaeology and biological anthropology from the Australian National University. He has written and lectured on Australian history, archaeology, Indigenous and European biological contact history and Australian cultural heritage assessment. He has a strong interest in military history and has organised and led local, national, and overseas tours in history, archaeology, and heritage. In a previous life, Dr Dowling spent twenty years in signals and electronic intelligence with the Royal Australian Navy. He saw active service during the Indonesian Confrontation and on escort ships, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Swan to Vietnam.

Thank you for stating this so well. It seems we now have to wait and see what results from what, at this point, seems short-sighted partisan political decisions being made determining the future of this iconic site.