‘Deluge: Great War and remaking global order’, Honest History, 7 July 2015

Adam Tooze’s book is reviewed by Derek Abbott*

________________

The causes of World War I are the source of seemingly endless debate. From Prussian military hubris or German anxiety, through the irresponsible brinksmanship of declining Empires, mechanistic determinism of mobilisation plans and railway timetables, to sleepwalkers, you pays your money and you takes your choice.

About the outcome of the war, however, there is significantly less dispute. A carthaginian peace at Versailles, French revanchism, British impoverishment and American isolationism, between them left a bankrupt, diminished and humiliated Germany easy prey for right wing extremism, et voila, the World War II.

But Adam Tooze will have none of this. In his view ‘what the war gave rise to was a multisided, polycentric search for strategies of pacification and appeasement’. Out of the violence of the Great War it seemed that a new international order was emerging. Winston Churchill wrote in The Aftermath, the final volume of The World Crisis, published in 1929, that ‘The period of repulsion from the horrors of war will be long-lasting; and in this blessed interval the great nations may take their forward steps to world organisation…’. Entertainingly, Tooze cites in support of Churchill’s argument the gloomy views of Hitler and Trotsky, also in 1929, about the prospects for their own revolutionary projects.

But Adam Tooze will have none of this. In his view ‘what the war gave rise to was a multisided, polycentric search for strategies of pacification and appeasement’. Out of the violence of the Great War it seemed that a new international order was emerging. Winston Churchill wrote in The Aftermath, the final volume of The World Crisis, published in 1929, that ‘The period of repulsion from the horrors of war will be long-lasting; and in this blessed interval the great nations may take their forward steps to world organisation…’. Entertainingly, Tooze cites in support of Churchill’s argument the gloomy views of Hitler and Trotsky, also in 1929, about the prospects for their own revolutionary projects.

Churchill’s optimism was founded on the apparent success of the international community in managing post-war disputes, including post-Versailles conflicts over both territory and reparations, and moving towards a stable international order, exemplified by the Washington Naval Agreements and the Locarno pact. Tooze examines the emergence of the USSR, fascism in Italy, the rise of Japan and the changing situation in China and, while acknowledging the contributions of these factors to instability and tension, concludes that the international order at the end of the 1920s had proved surprisingly resilient.

Inevitably, at the centre of Tooze’s book is the emergence of the United States and its relations with the victorious Allies. Wars have to be paid for and by 1918 it was largely US capital that was funding the Allies. Already by the end of 1916, ‘American investors had wagered two billion dollars on an Entente victory’ and this money had been raised largely through JP Morgan. The sums continued to mount; in June 1917 congressional foot-dragging on a three billion dollar loan brought Britain ‘within hours of insolvency’. The preparatory barrage at Passchendale cost an estimated $US 100 million.

By the end of the war British public debt was more than six billion pounds, up from six hundred and ninety million pounds in 1914. Servicing this debt consumed 25 per cent of the budget in 1919. In France and Italy the situation was proportionately worse. The economic consequence of the war was to leave the United States in a position of financial dominance that far exceeded that enjoyed by any previous great power but ‘the central irony of the early twentieth century [is that] at the hub of the rapidly evolving, American-centred world system was a polity wedded to a conservative vision of its own future’.

In gauging the US approach to the post-war world Tooze sees President Wilson’s proposal for a ‘peace without victory’, put to the US Congress in January 1917, rather than the later Fourteen Points – or, indeed the Versailles Treaty – as the better guide. The US remained distrustful of all sides in the conflict, hostile to the imperialism of Britain and France, suspicious of their intentions vis a vis Germany and opposed to Britain’s sea power as a threat to freedom of navigation. This was not isolationism; rather, it foreshadowed a new international order conforming to America’s view of its own exceptionalism.

Tooze poses the question, ‘Why did the Western Powers lose their grip in such spectacular fashion [in the 1920s]?’

[T]he answer must be sought in the failure of the United States to cooperate with the efforts of the British, French, Germans and Japanese to stabilize a viable world economy and to establish new institutions of collective security.

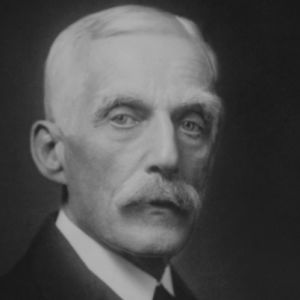

Andrew W. Mellon, US Secretary of the Treasury, 1921-32 (Biography.com)

Andrew W. Mellon, US Secretary of the Treasury, 1921-32 (Biography.com)

Post-war, the victorious European powers clearly understood that their capacity for independent action was constrained by their indebtedness to the US. They wished to draw the US into greater involvement in restructuring international finance and providing security guarantees to France. The US resisted; there would be no international financial settlement that linked reparations and allied war debts to the US. Ironically, America was supportive of German efforts to ease the burden of reparations but resistant to any reduction in British and French debt repayments. Similarly, she would not cooperate with Britain in any substantive guarantee of French security, particularly where that involved accepting the right of a belligerent to impose a naval blockade.

Far from being driven by a desire for revenge, France was motivated primarily by security and financial anxieties. The devastation wrought in her northeast by the war and German occupation convinced France that a binding international guarantee of her security involving the US and Britain was essential and that reparations from Germany were vital to funding the reconstruction of her devastated territory.

Britain was also learning the new realities of the post-war world. The growing nationalist movement in India (particularly the hostile response to the killings at Amritsar), difficulty in asserting control over her new acquisitions in the Middle East and the Chanak crisis showed that Britain was no longer in a position to maintain her Empire by force and that even the Dominions could not be relied upon to support her unquestioningly, as they had in 1914.

Thus, throughout the 1920s a series of international agreements on disarmament, boundary guarantees, debt and reparations showed the preparedness of the European powers to face the new realities. However, at its core the international economy was fragile and the policy prescriptions that dominated its management were inadequate to deal with a major crisis.

The return to the Gold Standard by major nations in the 1920s was seen as a touchstone of responsible behaviour, particularly by the Americans.

The gold standard was tied to visions of international cooperation that went beyond technical discussions amongst central bankers… [it] was “knave proof” not just with regard to big-spending, inflation minded socialists…[it] also constrained the militarists …

In Tooze’s view it was the commitment to the gold standard and the deflationary domestic policies that supported it that turned the financial crisis of 1929-30 into the Great Depression that shattered this emerging system of international cooperation and, in Germany, destroyed the fragile base of the Weimar Republic. The governments that came to power in Japan and Germany would argue that their countries had gained nothing from cooperation and that nationalistic self-interest would serve them better.

Unemployed, Berlin, 1932 (Wikimedia Commons/Bundesarchiv)

Unemployed, Berlin, 1932 (Wikimedia Commons/Bundesarchiv)

No doubt as centenaries come and go there will be a steady stream of books examining this period. Deluge is a rewarding comprehensive introduction to the issues and a challenge to established views.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer, with a history degree from Aberdeen University. He was a research assistant to Oliver McDonagh and Barry Smith at ANU and has a long-standing interest in military history.