‘Churchill and Gallipoli: a personal commentary’, Honest History, 7 June 2016

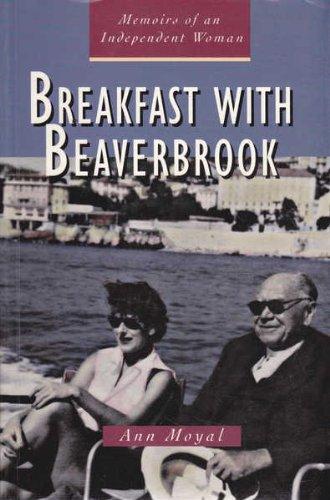

I have long enjoyed a personal and historical interest in Sir Winston Churchill. As a highly privileged young research assistant to Lord Beaverbrook, I spent a month in July 1958 at Beaverbrook’s villa in the South of France. Sir Winston, weakened by several strokes, was Beaverbrook’s honoured and cherished guest.

Anxious to entertain and stimulate his friend, Beaverbrook invited me, as an Australian, to sit with Churchill and tell him how proud Australians were of his role in the Dardanelles campaign. But I could not do this. My mother had lost her fiancé in the early fighting at Gallipoli and, as a child of her later marriage, I was reared in that generation of remembrance of brave men. Beaverbrook, however, was not easily thwarted, and soon had me swimming up and down in the villa’s illuminated pool, performing for this great national figure a particularly graceless edition of the Australian crawl. I swam for Churchill![1]

Anxious to entertain and stimulate his friend, Beaverbrook invited me, as an Australian, to sit with Churchill and tell him how proud Australians were of his role in the Dardanelles campaign. But I could not do this. My mother had lost her fiancé in the early fighting at Gallipoli and, as a child of her later marriage, I was reared in that generation of remembrance of brave men. Beaverbrook, however, was not easily thwarted, and soon had me swimming up and down in the villa’s illuminated pool, performing for this great national figure a particularly graceless edition of the Australian crawl. I swam for Churchill![1]

In subsequent decades my research and writing stirred a serious respect for Churchill’s overall strategy at the Dardanelles and, enduringly, a deep admiration and gratitude for his capacity and staunchness in saving Britain and Western civilisation in World War II. He was, in the words of Churchill specialist, David Dilks, ‘the most remarkable statesman of the twentieth century’ and ‘one of the century’s heroes’.[2]

Yet sometimes the human element, rising unanticipated, confronts one. I recently posted on The Strategist a paper, ‘Twelve days at Anzac: the evacuation’, describing the brilliant conceptualisation and courage associated with the withdrawal of 83 000 British, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops from Gallipoli and Suvla Bay on 8-20 December 1915 without a single loss of life.[3]

Churchill’s part as First Lord of the Admiralty in initiating and pursuing the strategy for forcing the Dardanelles by sea and land had been pivotal and even when, the victim of political criticism and hostility, he was removed from his Admiralty post in May 1915, he had remained an ardent spokesman for reinforcement of the theatre. Still a member of the Dardanelles Committee, he made preparations to visit Gallipoli in July, but Prime Minister Asquith cancelled his journey on the eve of his intended departure.

Cast out of his ministerial role and removed from his position on the Dardanelles Committee in November 1915, Churchill was condemned to remain a spectator in those last months of fighting on the Peninsula. His wife declared, ‘I thought he would die of grief’.[4] On 11 November he resigned from the derisory post which Asquith had given him (Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster) and, ‘placing himself at the disposal of the military authorities’, left for France a week later to join his own regiment, the Queen’s Oxfordshire Hussars, as Major Churchill.

It so happens that in a quiet period I have been rereading Mary Soames’ notable biography of her mother, Clementine Churchill. While Churchill was in France, either in or near the frontline or as a respected figure at GHQ in close contact with the Commander-in-Chief, Sir John French, he and Clementine exchanged letters almost every day. Their uncensored correspondence, rich in personal and political gossip and information, passed swiftly through GHQ with postal ease. ‘Their biographers – and indeed posterity’, writes Soames, ‘must ever be grateful that both Winston and Clementine were able to take advantage of a special privilege’.[5]

The Churchills, January 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/New York Times)

The Churchills, January 1915 (Wikimedia Commons/New York Times)

I read the letters now against my contemporary perspective of the critical state of Gallipoli in November 1915 and those crucial twelve December days of planning and initiating the withdrawal of troops from the Peninsula. I am struck by the profound disjunction of the Churchills’ correspondence between the dying days of a Dardanelles policy, on which he had expressly stamped his name, and the seeming carelessness, distancing and self-preoccupations of his concurrent life.

’Winston’s letters’, his daughter tells us, ‘nearly always included an urgent demand for food or other comforts’.[6] Six days after reaching France, he wrote Clementine on 23 November 1915, ‘Will you send now regularly once a week a small box of food to supplement the rations. Sardines, chocolate, potted meats, and other things wh [sic] may strike your fancy.’ Two days later he wrote, ‘Will you now send me 2 bottles of my old brandy & a bottle of peach brandy. This consignment may be repeated at intervals of ten days.’

The lists grew:

I want 2 more pairs of thick Jaeger draws [sic], vests & socks (soft). 2 more pairs of brown leather gloves (warm); 1 more pair of field boots (like those I had from Fortnum & Mason) … Also one more pair of Fortnum & M’s ankle boots only with tags right up from the bottom hole … Also send me a big bath towel, I now have to wipe myself all over with things that resemble pocket handkerchiefs.[7]

Clementine’s response was prompt and caring. ‘The most divine & glorious sleeping bag’, her husband wrote gratefully on 10 December, ‘has arrived’.

Essentially, Churchill’s interests and communications now turned on the question whether he would be given a brigade in France, as he hoped, or, as his wife, alert to likely political ‘criticism and carping’ in London, more cautiously advised, he should accept a battalion. But, writing to her husband on 15 December, Clementine disclosed that she had learnt that Sir John French, soon to be replaced as Commander-in-Chief by Sir Douglas Haig, ’had determined to give you this Brigade as he was convinced you would otherwise be killed’.

It was, however, not to be. To Churchill’s considerable chagrin, Asquith denied him a brigade.

My darling Love [Clementine wrote on 17 December], I live from day to day in suspense and anguish. At night when I lie down I say to myself Thank God he is still alive. The 4 weeks of your absence seem to me like 4 years – If only My Dear you had no military ambitions. If only you would stay with the Oxfordshire Hussars in their billets … Just come back to me alive that’s all.[8]

News of Gallipoli itself was elusive. Moving in political circles, lunching in fine restaurants, entertaining senior figures Churchill wished her to contact, Clementine informed him on 15 December that ’Rumours of the Dardanelles Evacuation are of course all over London (the usual W.O. leakage, I suppose) but the rumours differ’.[9] And at last, again without comment and with no response from Churchill, she transmits on 20 December: ‘Large posters put out: – TROOPS WITHDRAWN FROM DARDANELLES’.[10]

When one assesses this private correspondence it would seem that, in this vital period for the forces on the Peninsula, the Churchills appeared to experience a comparatively privileged and sheltered war, distanced from and without personal concern for the dramatic events taking place across the world on the Peninsula. Yet, despite his disappointment over the brigade, Churchill remained buoyant. ‘Believe me’, he wrote to his wife, ‘I am superior to anything that can happen to me out here. My conviction that the greatest of my work is still to be done is strong within me.’[11]

Churchill would remain in France for five months, initially with the Grenadiers and subsequently in charge of a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. But, convinced that his duty and destiny lay in taking part in his country’s political life, he returned to England in April 1916 to resume his seat in the House of Commons. It was then, as his daughter expressed it, that ‘the responsibility for that disastrous episode [the Dardanelles] still lay heavily upon his shoulders’.

Anzac Cove, December 1915, just before the evacuation (AWM 03482)

Anzac Cove, December 1915, just before the evacuation (AWM 03482)

Churchill, she records, was to bear the burden and public opprobrium for his role in the campaign ‘in a continued and harassing defence of his own responsibilities at the Dardanelles’.[12] Eventually, following an Interim Report from the Dardanelles Commission in 1917, which assigned a more widely shared responsibility for the policy and its administration, Prime Minister Lloyd George appointed Churchill as Minister for Munitions in the Coalition Government in July 1917.

As Mary Soames underlines, the publication of private letters provides an important legacy for historians. To plumb the intimate correspondence of Winston and Clementine Churchill offers a particularly illuminating insight into their shared devotion, close communication and supportive care. Yet, juxtaposed and set in their particular and vital time frame, the letters also offer an unexpected glimpse of varieties of human conduct and egocentric attitudes that linger disconcertingly in a historian’s mind.

Ann Moyal AM is a distinguished historian of Australian science. She lives in Canberra.

[1] Ann Moyal, Breakfast with Beaverbrook: Memoirs of an Independent Woman, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1995.

[2] David Dilks, Churchill and Company: Allies and Rivals in War and Peace, IB Tauris, London, 2014, p. vi.

[3] Ann Moyal, ‘Twelve days at Anzac: the evacuation’, The Strategist, 18 December 2015.

[4] Mary Soames, Clementine Churchill, Cassell, London, 1979, p. 122, quoting Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol.3, p. 431.

[5] Ibid, p.137.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, p. 145.

[9] Ibid, p. 144.

[10] Ibid, p. 149.

[11] Ibid, p. 145 (letter, 15 December 1915).

[12] Ibid, p. 184.