Australia’s Vietnam War – and keeping it in context: others in the series

‘The Battle of Long Tan turns fifty – but not without a hitch’, Honest History, 18 August 2016 updated

An article by Mark Schliebs in The Australian of 15 August reported that the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Long Tan was to be commemorated by Australians at the site of the battle. After that, we heard that the ceremony at the site was off and there would only be a small wreath-laying ceremony and no large gathering. Then later we heard that people will be let through during the day in groups of no more than 100.

Long Tan happened from 18 to 21 August 1966, when soldiers from Australia’s first Task Force at the new Australian base at Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy province clashed with a much larger force of Vietcong and North Vietnamese. Eighteen Australians were killed, along with a much larger number of Vietnamese. The Australians were supported by artillery and helicopters and the battle was claimed as a victory by the Australians.

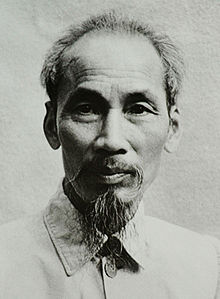

Ho Chi Minh (Wikipedia)

Ho Chi Minh (Wikipedia)

We do not really know what the Vietnamese today think about the clash. To them, the Vietnam War was a civil war, in which patriotic Vietnamese were fighting to rid themselves of an unpopular and corrupt regime in the South propped up by the United States. Furthermore, the Geneva Agreement of 1954 specified that elections were to have been held throughout the country in 1956. Ho Chi Minh would certainly have won these elections, and the country, temporarily divided at the 17th parallel following the defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu, would have been peacefully united under him. But the South Vietnamese regime under Ngo Dinh Diem refused to participate in the elections, the 17th parallel became a permanent border and the war resumed. Millions of civilians and military were killed before Saigon fell to Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces at the end of April 1975.

The United States militarily and politically backed the South Vietnamese regime until widespread popular objection throughout America made further support for the South unsustainable. US forces largely withdrew in 1972, leaving the South to fight on alone.

Under Robert Menzies, Australia joined the United States in sending forces to South Vietnam from the early 1960s, first military advisers, then Australian battalions. These were first based with the Americans, then given a province of their own, Phuoc Tuy, to defend and pacify. The Australian Army was supported by air force and naval units but, altogether, the force was token, more a premium on an insurance policy for American assistance under the ANZUS Treaty than a genuine attempt to stop Communist ‘expansion’.

This did not, however, stop former Diggers from demanding recognition for their gallantry, nor the ‘ANZAC’ industry from demanding the same. As in all wars engaging Australians, this one was overseas, and little thought was given to its rights or wrongs, to the outcome, or to how much damage was being sustained in the host country. Pressing for a commemoration to be held where the battle actually took place showed a degree of insensitivity towards the host country by the Australian organisers. Veterans should realise that Long Tan is not Gallipoli.

Long Tan cross (Australian Government)

Long Tan cross (Australian Government)

What is surprising is that, given the bitterness of the war and the enormous number of Vietnamese civilians killed by US forces and their allies, the Vietnamese Government in Hanoi has permitted Australian celebrations of Long Tan to take place at all, even in an attenuated form. But, in my experience, the Vietnamese are very pragmatic. Australia is a good trading partner and it is useful to keep Australians on side.

One would have thought that allowing Australia to celebrate a battle and a defeat of larger enemy forces on Vietnamese soil would have cost little and not upset the burgeoning bilateral relationship. There was even a plan to allow participants on the Vietnamese side from the Vietcong’s 275th Regiment and the D 445 Provisional Mobile Battalion to meet the Aussies over a meal. It seemed that the only betrayal of sensitivity on the Vietnamese side was going to be to forbid the Australians to wear their uniforms and medals or to talk to their hosts about the battle. Now there seems to be more to it than that; it will be interesting to see what official explanations are offered on both sides.

A later version of this post appears in Pearls and Irritations.

Richard Broinowski was Australian Ambassador to Vietnam from 1983 to 1985.