Australia’s Vietnam War – and keeping it in context: others in the series

Willy Bach

‘A “kick in the guts”? A final look at Long Tan’, Honest History, 30 August 2016

I am happy to say there were others who agreed with me on the question of Long Tan commemoration. For example, Mike Carlton tweeted, ‘What would we think if thousands of Japanese wanted to descend on Darwin to celebrate the [1942] bombing of Darwin’. We should reflect on that hypothetical question.

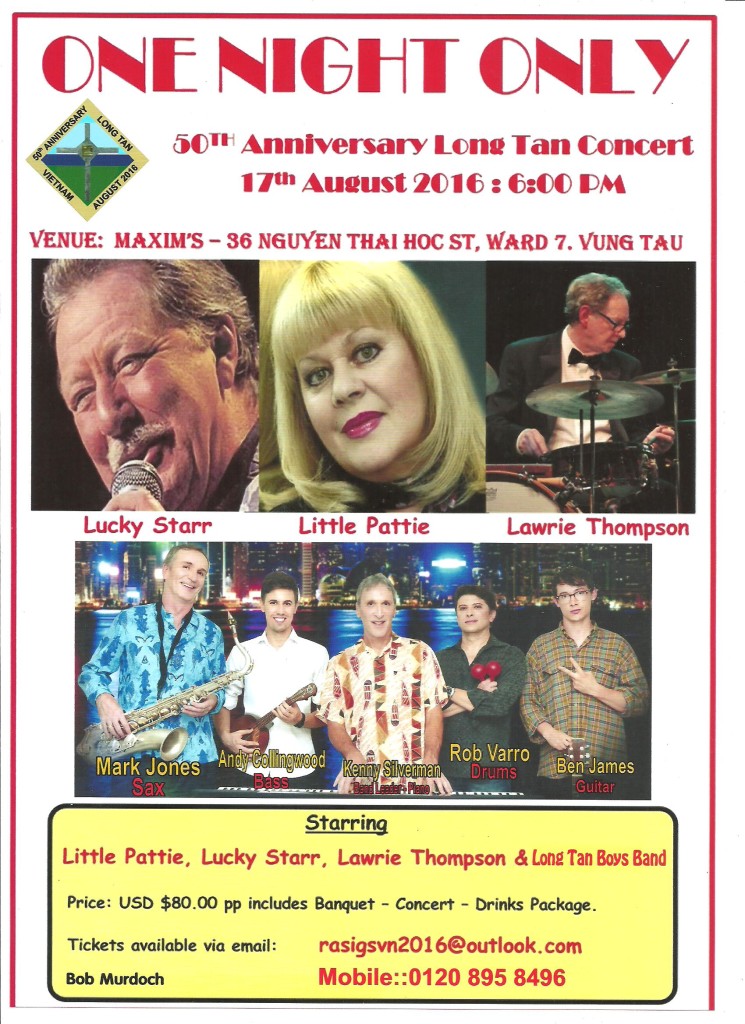

Concert promo (auschamvn)

Concert promo (auschamvn)

The Vietnamese government had decided to grant access to the Long Tan cross to small groups of Australians but reversed the decision when it was realised how big the throng was and how much world media the event was generating. Australia’s Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Dan Tehan, made an unfortunate choice of words when he called the reversal of this decision a ‘kick in the guts’ – no doubt Chinese energy suppliers seeking a slice of the New South Wales power industry have a word for late reversals, too. But Australia applies different standards to people who can be harangued, especially on matters Anzac.

There were 1000 veterans in Vietnam plus their families, possibly as many as 3000 Australians in Vietnam altogether. The organisers wanted to parade with uniforms and medals, make speeches, display banners and flags and play the Last Post. Then there was to be a banquet dinner at $A100 a ticket, including alcohol at the five-star Pullman Hotel, Vung Tau, with a performance by former teen singer, Little Pattie. That element alone had a festive flavour to it and looked like a celebratory knees-up.

The commemoration program as a whole would have appeared to the Vietnamese like a victory parade, an event which would not have been granted to United States military veterans. That prospect was all too confronting for the Vietnamese, many who still survive and live with painful memories of the war and its horrors and who had far more soldiers killed at Long Tan than did the Australians. It is also of some significance that 3000 people would trample a farmer’s corn crop into the ground.

In an ABC Radio National interview, Dr. John Blaxland, a Senior Fellow at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the ANU, said that the Australians found 245 Vietnamese bodies after the Long Tan engagement, but there were probably many more. Superior weapons and the New Zealand artillery more than made up for the Australians of 6RAR being outnumbered. The Australian narrative should not de-emphasise the role of artillery, which the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops lacked.

Meanwhile, the Vietnamese have long ago declared Long Tan as a win for their side, perhaps understandably, since they won the war and unified their country. The war narrative for them has already been established. The Australian commemoration disrupted this probable Vietnamese exaggeration but perhaps there is no particular right to impose the version Australians prefer. With the help of the unwanted world media attention, the Australian narrative would have carried to distant parts and many Vietnamese would have been very upset by this.

This incident reflected on Australia’s insensitivity to the culture and feelings of Asians and on our lingering white swagger. Blaxland described this politely as Australians ‘not being good at reading the tea leaves’. Remember the insult felt by Indonesians, Malaysians, Filipinos and Thais when John Howard declared that we were the American deputy sheriff in the Pacific – the offence was palpable. In the tradition of Imperialist masters, Howard felt entitled to dish out this offence and never apologised. Now that Pauline Hanson has been elected, our neighbours are asking themselves whether they will feel safe when they visit Australia. I have heard the question and it saddens me greatly.

Repatriation of Vietnam dead, June 2016 (Guardian Australia/Himbrechts/EPA)

Repatriation of Vietnam dead, June 2016 (Guardian Australia/Himbrechts/EPA)

It is not the fault of the Vietnamese that the Australian veterans were not treated like heroes on their return to civilian life in Australia. The Vietnamese should not be expected to bear the pain the Australians felt. We should be more respectful and not expect to be treated like lords when visiting Asia, as if we were reliving Britain’s colonial dominance.

Long Tan veteran Robert Buick thoughtfully commented that the 40th anniversary in 2006 would have been a shock when a group of Vietnam veterans from South Australia ‘behaved in a disgraceful manner at the cross that could have influenced the limiting of numbers visiting the site’. On the other hand, some comments from other veterans showed how little they understood about the war and the people of Vietnam. We can accept though that they had waited 50 years and had saved up all their money to return to the battlefield. They are getting old and some have health issues.

Some of these men and their wives were on buses to the Long Tan cross when they received the news that they would not be allowed onto the site. They had begun exchanging gifts with former Viet Cong soldiers who were invited to the dinner. Some Australians complained that the Vietnamese government was ‘duplicitous’, that we should recall the Australian Ambassador and lecture the Vietnamese government if it wanted to continue receiving Australian aid.

Fortunately there were calmer heads at DFAT and Minister Bishop didn’t do any of this. Some veterans claimed also that they had fought cleanly as professional soldiers and had nothing against their Vietnamese counterparts. This may well be the case. As Blaxland said, the Vietnamese don’t do memorials of battles and the Americans had no memorials in Vietnam – only Australia did this.

On this last point, Australian soldiers probably did fight cleanly (if there is such a thing) but, beyond what they saw of the war, it was a brutally and ferociously fought dirty war where the Geneva Conventions were dispatched into the oblivion of another universe. The war I have been studying includes the Phoenix Program, which caused the murder of up to 30 000 Vietnamese Viet Cong ‘suspects’. That war has no memorials, no Anzac legends and emphatically no heroes.

While my partner and I were in Laos in 2007-08 she felt swept up with remorse for what had been done to that country by the CIA and by US bombing. She asked our Lao language teacher how she could apologise. Our teacher was shocked and told my partner she must never do that. No apology would bring back the million people Laos had lost. Nothing would compensate either for 50 years of impoverishment of areas that still contain unexploded ordinace and cluster munitions.

Willy Bach is a postgraduate research student, School of History, University of Queensland.

Vietnam concert party members, 1967. The woman on the right, Catherine Warnes (stage name Cathy Wayne), was accidentally killed on a later tour, aged 20, when a disgruntled American soldier attempted to shoot his commanding officer and missed. The soldier was convicted but freed after a retrial. Warnes was one of three Australian women killed during the Vietnam War. (AWM ERR/67/0248/EC/WA Errington)

Vietnam concert party members, 1967. The woman on the right, Catherine Warnes (stage name Cathy Wayne), was accidentally killed on a later tour, aged 20, when a disgruntled American soldier attempted to shoot his commanding officer and missed. The soldier was convicted but freed after a retrial. Warnes was one of three Australian women killed during the Vietnam War. (AWM ERR/67/0248/EC/WA Errington)