Honest History’s President, Professor Peter Stanley, reviews and reflects on James Brown’s new book, Anzac’s Long Shadow.

James Brown, Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession, Black Inc, Melbourne, 2014, $19.99; also available electronically

James Brown, former officer in 2 Cavalry Regiment and a veteran of Iraq, the Solomon Islands and Afghanistan, has single-handedly opened up a new front in the intermittent debate over the nature, relevance, justification and value of Anzac and its observance in Australia today. (Some people insist that this is a ‘history war’ but Honest History, at least, tries to bring the ‘sides’ together with its motto of ‘Not only Anzac but also’. Anzac is clearly an important part of our history but there are many other equally important historical strands that need to be known and studied.)

Hitherto critiques of Anzac have come essentially from the academic liberal left. The most coherent articulation so far has been What’s Wrong with Anzac? by Marilyn Lake, Henry Reynolds, Joy Damousi and Mark McKenna. These authors not having served (in uniform or in war) their arguments could be and have been ignored or dismissed by Anzac’s traditional defenders as the protestations of those who either didn’t understand what military service means or had not ‘earned’ the right to speak about it. (I do not accept that these objections are valid, merely note that they are made.)

James Brown’s questioning of the need for or value of an ‘Anzac Centenary Merchandising Plan’ (as the Australian War Memorial unblushingly calls it) comes from a writer who has without question also been a doer. Brown argues that a ‘chasm’ exists between the people of Australia and the people of the Australian Defence Force and that the centenary of Anzac program conceived and endorsed by successive governments (‘so extravagant that it would make sultans swoon …’) is unjustified and is actually harming Australians’ ability to understand how their nation can use armed force as a legitimate instrument of national interest, one undertaken by actual, live soldiers.

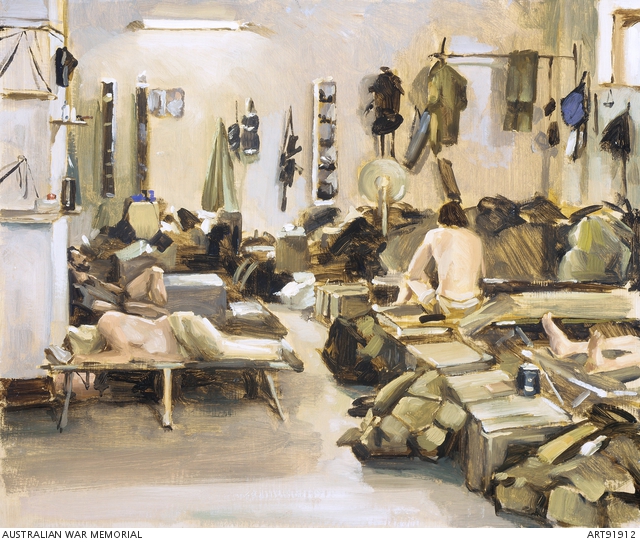

SAS sleeping quarters, Bagram Airforce Base, Afghanistan, 2002 (source: Australian War Memorial ART91912; painting: Peter Churcher)

Brown argues that Anzac Day is now marked by ‘jingoistic commemoration’. He writes that we have ‘Disneyfied the terrors of war’. We venerate those who served in past wars, wrapping up our admiration in so many layers of ceremony and ritual that real soldiers – men and women who have returned from Iraq and Afghanistan – are ‘increasingly standing to one side’. Brown’s critique ought to worry the custodians of the Anzac legend and those who exploit it through what he calls the Anzac Industry.

(Am I a part of the Anzac Industry? I suppose I am: I have made a good living from writing about Australian military history, almost all before 1945 and latterly mainly about the Great War – precisely the bits that Brown thinks are least relevant and most dangerous. But I am also regarded as a critic of the application of the idea of Anzac – to the unjustified manifestations of which Honest History has drawn attention – a critic of the unthinking adulation of Anzac. This is a complex matter of argument and allegiance, of critique and connection – discussed here – but if I keep doing what I do I don’t think I am harming the honesty and realism he advocates.)

Not that I necessarily accept all of Brown’s contentions. For example, I think that he has read Lake and Reynolds wrongly: I think that the continuing adulation of Anzac will foster a militaristic society, not in the sense of re-creating a Prussian junker clique – Brown deliciously spears Mervyn Bendle’s predictably spit-flecked sarcastic rant – but in the sense that unchecked Anzackery will make less bellicose alternatives harder to put or accept.

Does Brown over-egg the pudding when he claims that members of the ADF who have returned from recent conflicts have been spurned? It seemed that Australia learned a lesson from the Vietnam years, when returning soldiers were wrongly blamed for Australia’s involvement in an unpopular and unjustifiable war. How can we have got it wrong again?

Two SAS with Simpson the donkey in the Australian compound, Bagram, Afghanistan, 2002 (source: Australian War Memorial ART91913; painting: Peter Churcher)

But according to this young, thoughtful veteran we have got it wrong; we need to listen to what he has to say. This time we seem to be getting it wrong by trying too hard to laud soldiers without troubling to find out much about what it is that they do that is different to what the Diggers did in the world wars, the heart of our Anzac preoccupation. We have made so much of what Brown calls our ‘obsession with dead soldiers’ that we have not made enough of the live ones who have returned, often damaged by their experience in ways we have not acknowledged and have not done enough to fix.

Brown’s book is not long – just 160-odd pages – but it covers a lot of ground. He reminds or (probably) introduces us to what fighting in Afghanistan entailed. Since (he writes) successive Australian governments actively suppressed or managed reporting of Australia’s war, it is not surprising that some of his account seems novel. His concern that the needs of Australians returning from that war are being ignored at the expense of many hundreds of millions of dollars being spent on a four-year Anzac-themed Halloween party fuels a work of exemplary advocacy.

Brown is not disillusioned about Australia having taken part in recent wars in West Asia. He is not bitter that Australians died for a cause he clearly believed in and still contends was worthwhile. But he is profoundly disturbed by decisions made by Australian political and military leaders, by their failure to make (and stick to) clear decisions, by their failure to tell us what they were doing and why, by their willingness to allow the deaths of Australian personnel to shape what they did and how they presented and justified Australia’s involvement.

It was, Brown writes, ‘no way to run a war’. He describes how, so caught up in the rituals of remembrance had Australia’s leaders become that in August 2012 the prime minister, the defence minister and the chief of the defence force cancelled their programs to attend yet another military funeral. Brown laments the deaths of ADF personnel but even more he laments that ‘our leaders return to grieve over the bodies of dead soldiers, rather than focus on Australia’s strategic future’. He realistically accepts the need for the state to deploy armed force but he wants it to be governed by rational decisions, not by a sentimental and dysfunctional regard for the long-dead citizen soldiers of a century ago.

Brown is particularly bothered by what he sees as a widening gap between what war means for ADF personnel today and how war is perceived and represented in the Australian community. He shows that the Anzac legend as it has become celebrated often alienates today’s soldiers, who cannot discern a resemblance to what they do today in the portrayal of gutsy Diggers performing heroic deeds in battle while laconically ribbing their officers and refusing to salute. (See Chief of Army David Morrison in similar vein.) This, he says, is not how ADF members look or behave in or out of action today and he wants to see us laud the soldiers who serve us now, not those who served the Australia of a century ago. He reviews a contention familiar to Australian military historians, that the Anzac legend has emphasised citizen diggers performing heroic actions in battle at the expense of military professionals performing less spectacular but often more substantial functions. Commemoration, he says, has crowded out serious thought.

Dawn, Iraqi waters, Arabian Gulf, 2007 (source: Australian War Memorial ART93290; painting: Lyndell Brown, Charles Green)

Anzac’s Long Shadow takes issue with the supposed custodians of the Anzac spirit, arguing that the RSL and its ilk (often no longer actually veterans) do not represent today’s younger veterans – who have very different experiences of war – and claiming that these younger men and women feel left out of the very events and ceremonies of Anzac Day. He is affronted that ‘Anzac is being bottled, stamped and sold’ by national institutions such as the Australian War Memorial and Australia Post – as are many other Australians, regardless of whether they served in the ADF or not. He is disgusted that Australia will be spending up to $625 million on the Great War centenary, many times more than, say, Britain, and certainly more than any other nation proportional to population.

Part of Brown’s outrage comes from the realisation that Australia will mark the centenary as a ‘discordant, lengthy and exorbitant four-year festival for the dead’. He is particularly outraged at the RSL’s endorsement of the cynical marketing of Foster’s ‘Raise a Glass’ campaign at a time when alcohol-related trauma is destroying the lives of serving and former soldiers. (And good on RSL Queensland for declining to join in the campaign.)

Australians, Brown argues, hold deeply paradoxical attitudes. On the one hand, they live in a country so remote from actual military threat that they rarely see uniformed soldiers (except, ironically, on Anzac Day) and often have a vague understanding of what the ADF is and what it does. (‘We have a full-time army?’ he quotes an investment banker asking at a party. ‘I thought we just had reserves …’.) And at the same time, he argues, Australians are fascinated by their military past but only by the glorious Anzac bits, not the hard bits involving using Australian military force in today’s very different world.

So pervasive is this Anzac devotion, Brown writes, that it is damaging the way serving ADF personnel think about what they do. One of Brown’s contemporaries told him that his soldiers ‘don’t feel that they lived up to the Anzac legend’. He quotes an ADF psychologist who has found ADF people finding difficulties in relating their own complex technological jobs to the ‘larrikin bushman image’ of the Digger of the world wars. The ‘Anzac spirit monkey’ is riding on their shoulders.

Brown asks, ‘Have we got our remembrance right?’ – a question Honest History has asked, from a different starting point – and he contends that Australia is ‘overinvesting in commemoration on the basis of a superficial understanding of … war’. While he may base his critique of Anzac on quite different assumptions, it complements the analysis Honest History commentators have offered. Brown’s concern, for example, about misrepresentations of the Anzac experience in popular history is echoed by historians who criticise the unjustified emphasis on front-line heroes who fight bravely at the expense of ignoring the long-term effects of war on the entire society. His worry that children are subject to ‘a national program of Anzac inculcation’ is exactly what Honest History’s curriculum experts have argued against.

Captain Rachel Leal of 1st Intelligence Battalion holds a baby on a visit to inform villagers of the progress of the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI), in the troubled region of north Malaita, 2003 (source: Australian War Memorial P04223.673; photo: Stephen Dupont)

Anzac’s Long Shadow offers a welcome triangulation on the ‘What’s Wrong With Anzac?’ debate that has been a part of our nation’s conversation for the past several years. Lines from Brown’s book could have come from Honest History’s website: ‘By glossing over some of the painful truths of soldiering, we run the risk of distorting the next generation’s understanding of war and what it means to fight for something you believe in.’

Anzac’s Long Shadow demonstrates that it is not just left-liberal peacenik rat-bag mouthy academics who worry that Anzackery is getting out of hand. Here is an intelligent, thoughtful veteran of overseas wars who shares that concern and who argues that the sentimentality and untruthfulness surrounding Anzac needs to be replaced by honesty and clarity.