‘“Visitation” numbers at the Australian War Memorial since 1991: is this joint really jumpin’?’ Honest History, 2 February 2016 updated

The title of this piece needs some explanation. First, ‘visitation’. The author thought this word meant the visit of a bishop or archbishop to a church in the diocese or, less often, an appearance of a divine or supernatural being. Its use by the Australian War Memorial in lieu of ‘visits’ and ‘visitors’ seemed to reflect the idea that the Memorial is a cathedral of the ‘secular religion’ of Anzac. However, it turns out that the word is also a common term in the museum and tourism fraternity. Always nice to learn something new.

Then, ‘the joint is jumpin’. This is the title of an old song by Fats Waller. It includes lines about checking your weapon at the door and ‘get rid of that pistol’, both of which have some relevance to the War Memorial’s line of business. But the song is really about visiting – or ‘visitation’ – and the reference to the joint jumpin’ seems appropriate to a venerable institution which, after a long history of presenting a sober and sad story in a certain way, has in recent years tried some new angles (voices in the cloisters, projections on the walls, dusted-off dioramas, celebrity soldiers, celebrity weapons, and so on) to tell the same old story.

But is the joint really jumpin’? In this article we analyse 25 years of War Memorial visitor statistics and seven years of statistics for the Memorial’s website. We start by noting the high visitor numbers at the Memorial in 2014-15. We compare these figures with domestic tourism into Canberra and then with Australia’s population over this period, to give us a ‘real’ figure for visitors to the Memorial. We look briefly at student visitor numbers and numbers visiting the Memorial’s travelling exhibitions.

We then turn to statistics for the Memorial’s website. We look at visits, visitors, unique visitors, page views, bots, bounce rates, views per day and visits duration and views per day. Someone had to, as the Memorial seems not to – or if it does it isn’t telling or not telling everything.

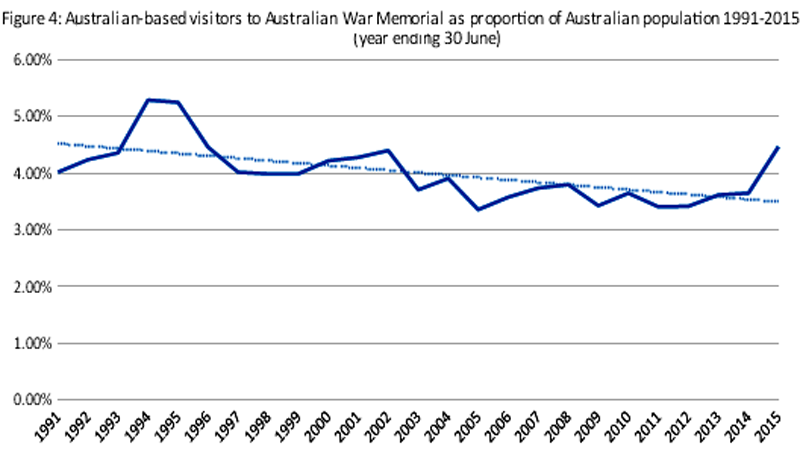

We conclude that the Memorial’s visitor numbers – real people walking through the door – have remained remarkably stable over a quarter of a century at around four per cent of Australia’s population. We then characterise the Memorial’s statistics about the virtual visitors to its website as a mixture of confusion and spin, even obfuscation. It’s a long article but we do not apologise for that; there are lots of sub-headings to guide the reader.

Beneath the copious statistics in the article are two propositions: first, that the Memorial’s actual visitor numbers since 1990 should lead us to question whether the Anzac legend’s hold over Australians is as strong as many of us thought; secondly, that the loose way the Memorial presents its website visitor statistics provides evidence of the need for national standards for website metrics.

2014-15: a big year for visitors

The Memorial does not have a publicly available historical series for visitor numbers so Honest History compiled its own, using the Memorial’s annual reports.[1] (The statistics are in an Excel spreadsheet.) In raw visitor numbers, 2014-15 was the best year yet for the Memorial: it welcomed 1 142 814 visitors, 24 per cent up on 921 300 in 2013-14, and 12 per cent above 1 019 279 in 1994-95, exactly 20 years ago. Twenty years ago, of course, was the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War I and 2014-15 was the beginning of the Anzac centenary. Anniversaries bring visitors. TripAdvisor reckons the Memorial is Australia’s top landmark and it ranks at number 17 world-wide, ahead of the pyramids of Egypt. War Memorial Director Nelson noted this achievement with justifiable pride.

A longer view of visitor numbers

Visitor numbers

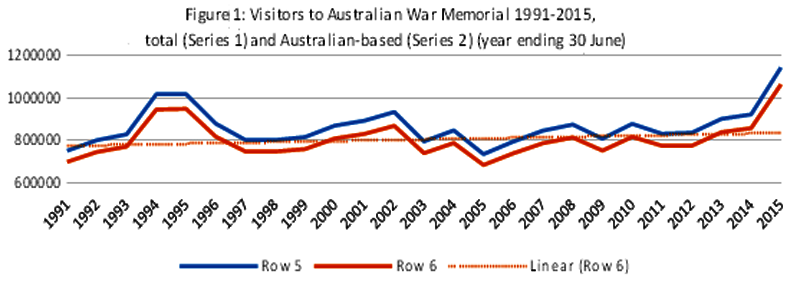

Figure 1 shows (in Series 1) Memorial visitor numbers for the 25 years from 1990-91 to 2014-15 and (Series 2) estimates for Australian-based visitors, that is, visitors who are not overseas tourists. For a reason that will become clear in a moment, it is the figures for ‘Australian-based visitors’ or ‘total visitors minus overseas tourists’ that we will use in this article. The Memorial advised Honest History that its General Visitor Survey indicated that seven per cent of its visitors were ‘visitors from overseas’. While we suspect this figure has risen and fallen slightly over 25 years we have used it across the complete period – in Figure 1, the Series 2 line (called ‘Row 6’ in the graph) is seven per cent below the Series 1 line (Row 5). Thus, the Memorial’s 1 142 814 ‘total’ visitors for 2014-15 becomes in our calculations 1 062 817. (We do not, in the analysis below, try to break down visitors into age groups, gender, interests or satisfaction levels. The Memorial’s annual reports include some of this material.)

What do these figures show? Given what we thought we knew about the growing popularity of Anzac and military history over the last quarter century it is surprising that there is in this period only a small increase in the annual number of Australian-based visitors to the Memorial – the very people who are supposed to be avidly following military and military-related family history. Rather, the numbers wax and wane around the average of just over 800 000 (803 584; the median is just under 800 000) and the trend line barely tips upwards.

The big recent exception to the ‘wax and wane’ pattern is, indeed, 2014-15, mostly due to the reopening of the World War I galleries against the backdrop of the Anzac centenary. The Memorial’s annual reports over the years have tracked previous visitor increases following new exhibits or other initiatives but not to the extent of this recent spike or the one between 1992-93 and 1994-95.

Tourism comparisons

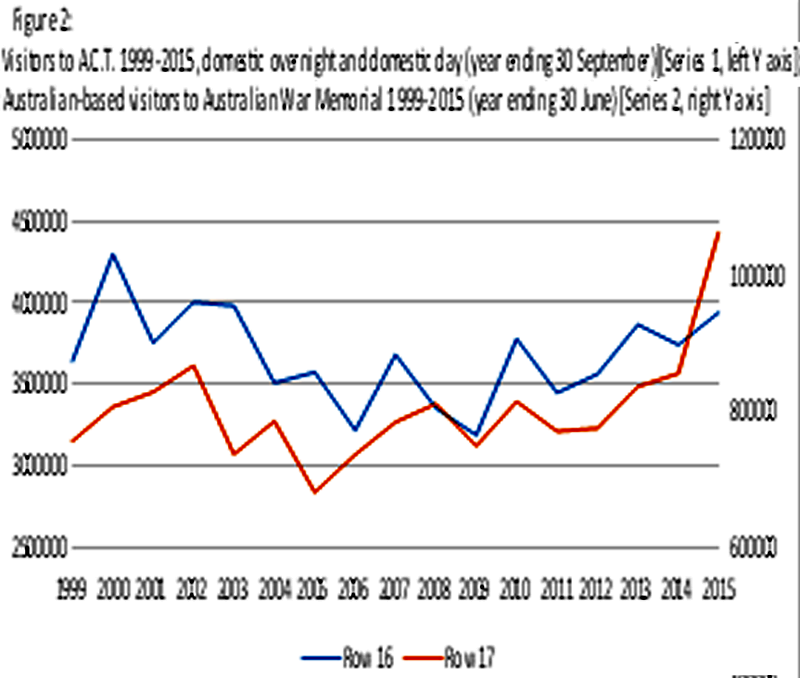

Memorial visitor numbers mirror overall domestic tourism into the A.C.T., shown in Figure 2 for the years 1998-99 to 2014-15 and which show a similar waxing and waning. (We have included on the graph the figures for Australian-based visitors to the Memorial in these years and provided a secondary Y axis to show this series. The graphs are not completely comparable because of the different year-end dates but the pattern is clear enough. ‘Row 16’ is Series 1; ‘Row 17’ is Series 2.) Indeed, the Memorial is one of the strongest drivers of the A.C.T. numbers.

Tourism numbers are affected by general economic conditions (good times put money in the pocket for discretionary expenditure) and many other factors. For example, the Memorial’s Annual Report 2002-03 speculated that numbers fell that year due to bushfires, SARS and war in the Middle East. Remarks about the factors driving tourism are a staple of the Memorial’s annual reports.

Visitor numbers as a proportion of population

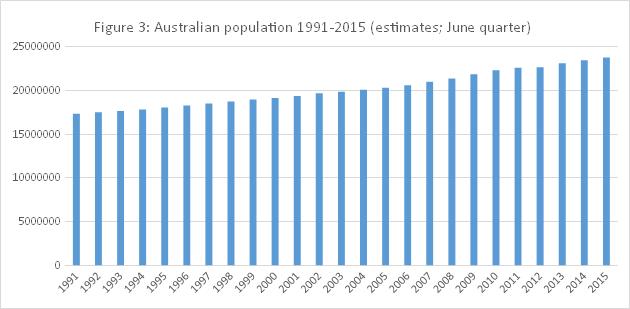

Now we come to why Honest History wanted to discount for overseas (not domestic) tourists. We needed to work out what proportion of Australians in any one year visited the Memorial. To do this we first collected Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates for Australia’s population over 25 years. This produced the steadily rising columns in Figure 3 as our population grew from 17.3 million in 1991 to 23.8 million in 2015.

Figure 4 then presents the result of our crucial calculation; it shows that, over 25 years, despite all the potential influences driving ‘visitation’ – from Anzackery[2] to cashed-up tourism to sound-and-light shows to Winged Victory, once the pride of Marrickville – the figure for annual Australian-based visitors to the Memorial continued to hover around four per cent of Australia’s population. The average over the quarter century was exactly four per cent, the highest proportion was 5.29 per cent in 1993-94 – 5.25 per cent in 1994-95, just 4.47 per cent in 2014-15 – and the lowest 3.36 per cent in 2004-05 with low proportions persisting for the next nine years. Our population grew steadily but Australian-based visitors as a proportion of our population did not; the trend line dips down.

The point of all this

Looked at another way, while in any one year since the early 1990s around four per cent of Australians visited the Memorial, 96 per cent of Australians in any one year did not. (This does not mean 20 per cent of our population visits the Memorial over five years because only about one-third of visitors in any one year are ‘first timers’: see, for example, Annual Report 2014-15, page 14 and the statistics in our Excel spreadsheet.)

In a time of commemoration, when euphoria is never far away, it is always useful to look at the other side of war-related statistics. Joan Beaumont in the preface to Broken Nation points out that, while some 417 000 Australians out of a population of fewer than five million enlisted in World War I, ‘most Australians stayed at home. Among men aged 18 to 60, nearly 70 per cent did not enlist.’ As Beaumont says, ‘the story of Australians at war is about more than the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) at war’. The same applies to commemoration. Certainly, 128 700 people went to the 2015 Dawn Service in Canberra (Memorial Annual Report 2014-2015, page xiv), easily a record and equivalent to one-third of the population of Canberra, yet, allowing for a good proportion of the crowd being from outside Canberra, more than two-thirds of the local population were not present.

This is not to deny that the Dawn Service may have been moving or significant for those who were there; it is just to say that the Service was not the only game in town. In a diverse, multicultural society with a wide range of interests the Service would have been treated as sacred by some people, a curiosity or anachronism by others, and many other things by the people in between (if they thought about it at all). If Anzac is a secular religion there are plenty of atheists and agnostics about.

Children at the gate

The Memorial does a lot of work with children, as Honest History has noted previously. Figure 5 shows trends in student visitors since 2006; sampling earlier years shows 70 000 in 1990-91 and 1991-92, 80 000 in 1994-95 and 101 000 in 2002-03. The number has risen steadily and by 2014-15 it had reached almost 140 000. (Students is essentially school groups and does not include children visiting with families.)

Under the PACER (Parliament and Civics Education Rebate) program, in existence throughout the period covered by the graph, students in Years 4 to 12 are subsidised for travel to Canberra, provided they visit Parliament House, the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House and/or the National Electoral Education Centre and the War Memorial. These are the mandatory destinations if schools want the money. One could ask ‘Why mandate the Memorial and not, say, the High Court, the National Archives, the National Film and Sound Archive, the National Gallery, the National Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, or Questacon?’ but that is a question for another day.

Travelling exhibitions

The Memorial’s travelling exhibitions program existed from 1997 to 2014. During that time 46 exhibitions toured to 485 venues throughout Australia, attracting 4.16 million visitors. In the most recent full year of operation, 2013-14, more than 197 340 visited the exhibitions (Annual Report, page 18). There will still be travelling exhibitions from time to time, such as the Spirit of Anzac Centenary Experience, currently touring. Travelling exhibitions are obviously much smaller than the Memorial proper and we have treated visits to them as separate.

Virtual visitation: how busy is the Memorial’s website really?

Visits

The way the Australian War Memorial presents its website statistics is a mixture of confusion and spin, even obfuscation. Research in the Memorial’s annual reports shows visits to the website rising from 2.8 million in 2008-09 to more than 7.3 million in 2014-15. (There is no point going back further than 2008-09 because the Memorial admits a faulty counting method before that date inflated the numbers: Annual Report 2008-09, page 14.) Still, visit numbers have obviously grown greatly over this time. Is this where the Memorial is reaping the whirlwind of interest in military matters? Have people shifted from visiting the Memorial in person to visiting virtually?

Visitors

Maybe. The plot thickens, however. The Memorial has also collected statistics for ‘visitors’ to the site, though it has not always distinguished between the two concepts: in the 2008-09 report, for example, we see references to both 2.8 million ‘visits’ (page 14) and 2.8 million ‘visitors’ (page 32). This is a bizarre statistic which assumes every visitor to the website makes just one visit in a year. It must be an error – or a red herring.

Whatever it was, it persisted. In the 2011-12 report, too, we see ‘over 3.6 million visitors to the website’ on page 14 and ‘3,697,800 visits to the Memorial’s website’ on page 26 (emphases added). Yet visitors and visits are not the same thing: a visitor could make ten visits to a site or could make just one. The confusion persisted even in the Annual Report 2014-15, 20 years after the Internet became almost a household utensil: ‘more than 7.3 million visitors to the website’ on page 14; ‘7,376,838 visits to the Memorial’s website’ on page 35 (emphases added).

There’s more. The way the Memorial presents website visitor/visit figures implies that walking through the door of the Memorial and interacting with its website are comparable – that an actual and a virtual visit somehow mean the same thing. Here are the two complete references from the Annual Report 2014-15, pages 14 and 35, which also complicate matters by throwing in the buzzword ‘visitation’:

Total interactions for this year included more than 7.3 million visitors to the website, more than 1.142 million visitors to the Memorial and its storage facility in Mitchell, 139,971 visitors to travelling exhibitions, and assistance with more than 32,469 research enquiries …

KPI 1 Number of visits to the Memorial’s website. Result: During the reporting period there were 7,376,838 visits to the Memorial’s website.

KPI 2 Number of people to make their first visit to the Memorial. Result: It is estimated that 336,698 people visited the Memorial for the first time during the financial year. This figure represents almost one-third of total on-site Memorial visitation (1,142,814 visitors) (emphases added).

Real and virtual visits are not the same and should not be conflated as these paragraphs do. Real visitors might stay for an hour or two; virtual visitors linger for just minutes, as we shall see in a moment.

Take your pick: visits, visitors or views

If the Memorial really did have 7.3 million visitors to its website in 2014-15 that would have been three out of ten women, men and children in Australia; impressive but probably not correct. By 2014-15 the Memorial did distinguish between visitors and visits although the visitor figure did not appear on the ‘Highlights’ page (page xiv) of the Annual Report, perhaps because it is much lower than the visits number and thus less impressive for public relations purposes. Buried on page 35 of the Annual Report, however, there is this, under the heading ‘Deliverable 1: an engaging website with accurate information’:

This year has seen a 62 per cent increase in visitation to collection items, with 3.29 million visitors looking at this material compared to 2.09 million last year. There was a 31 per cent increase in visitation to the biographical information on the site, up to 12.9 million views from 9.87 million last year (emphases added).

We now have a different number for visitors plus a reference to ‘page views’. But it seems that ‘collection items’ is less than the complete website – there is biographical information also – so we still don’t have an overall visitors figure for the whole website; instead, ‘visitation’ to the biographical data on the site is given to us in page views, a different metric again. Elsewhere we read about a total of more than 20 million page views for the year: Annual Report, p. xiv

Unique visitors

So the Memorial now has separate concepts of visits (with a number attached but sometimes called ‘visitors’), visitors (with an incomplete number attached) and page views (with another number attached). Leaving aside for the moment the unknown number of visitors to the biographical data on the site, an annual figure of 3.29 million visitors is still not bad. But how many of the visitors are ‘unique visitors’? Visitors and unique visitors, again, are not the same concept. ‘No matter … how many visits a visitor makes’, summarises another useful reference, ‘if he is on the same device and same browser, only one unique visitor is counted’. Google Analytics counts unique visitors, so does the package that Honest History uses, it’s easy enough to do.

So, the number of unique visitors to awm.gov.au might be a much lower figure than the number of visitors and much, much lower than the number of visits. There could be, for example, 329 000 unique visitors (actual humans) making ten visits each, to add to 3.29 million visitors, or there could be a million unique visitors each making 3.29 visits, to add to the same figure. If the 3.29 million is actually unique visitors why not say so rather than call them visitors, which is technically a different metric? Is there a lower, less impressive unique visitors figure that is not being revealed? Finally, do the statistics include Memorial staff using the website for work purposes?

Bots

Then there are bots. A proportion of visits to most websites is from bots (spiders) seeking commercial information or updating Google or other search engines – that is, the visits are not from ‘real people’, actual humans. Alexa, a web traffic analysis site, reckons that visits from search engines to the Memorial’s site rose steadily from 30 to 38 per cent between April and December last year. This figure excluded non-search engine bots; recent research suggests bots of all types account for nearly 50 per cent of traffic to websites.

Whatever the unique visitor number is, taking, say, 50 per cent away for bots leaves rather a dent. It seems important, though, to find a number for real, breathing users. But perhaps the Memorial has an efficient bot filter. Could it tell us about its experience with bots?

Bounces

To take another example, Alexa estimates ‘bounce rate’, which is a measure of engagement with a website. Essentially, bounce is when the user enters the site at a particular page but leaves without going to other parts of the site, that is, the user browses one page of the site then flits off to another site or turns on the TV instead or goes to bed. On 27 January, Alexa measured the bounce rate of awm.gov.au as a tick under 60 per cent. So, a clear majority of users of the Memorial’s site move off it pretty rapidly.

Visit duration and views per day

Web analysts warn that ‘bounce rate’ is a slippery statistic but, taken with two other Alexa estimates – that the average visitor to the Memorial site only stayed for three minutes per day and registered just under three page views per day – it shows the importance of not getting too excited about any website statistic in isolation. (We’ve already noted above that visit duration is a reason for not talking about virtual and actual visits in the same breath.)

To sum up, it would be nice to have the Memorial’s annual website numbers presented clearly in one place, without spin, confusion or obfuscation, including the key statistic of unique visitors. Perhaps the successful candidate for the Memorial’s advertised position of Head, Digital Experience, could tackle some of these issues and tell us the results. The loose grip the Memorial has on these statistics underlines the need for an Australian Standard on website statistics reporting.

Inauguration stone, courtyard and cloisters, Australian War Memorial, Dawn Service, Anzac Day, 1947 (AWM 100998/DH Wilson)

Inauguration stone, courtyard and cloisters, Australian War Memorial, Dawn Service, Anzac Day, 1947 (AWM 100998/DH Wilson)

Conclusion: sacred and profane

The word ‘sacred’ is often used in relation to Anzac; the opposite of sacred is ‘profane’, which simply means ‘not sacred’ or ‘secular’. The sacred and the profane are often mixed together; the suggestion that Anzac is a secular religion recognises this. It is appropriate that visitor numbers to the War Memorial – a cathedral or shrine of Anzac – seem to be driven just as much by profane factors, such as whether people can afford the trip or feel safe travelling (tourism figures being influenced by economic and other conditions) and their response to incentives (the Memorial’s promotions of new exhibitions, PACER) as they are by fond memories of previous visits and by patriotic fervour or reverence (attitudes to the Memorial as a sacred place).

This is not to say that fervour and reverence are unimportant – they are important for some visitors – but they need to be placed firmly in context. As for the Memorial’s website statistics, we come back to the sacred: the sacred always contains an element of mystery, as do the statistics for awm.gov.au. There has always been an element of myth-making and myth-peddling in the Memorial’s work; it should not extend to its statistics.

Update 7 February 2017: analysis visitor statistics in the Memorial’s Annual Report for 2015-16.

Notes

[1] Note on statistics. An Excel spreadsheet contains the raw figures used for the graphs in this article, along with information about where the data comes from. Most of the data is from the War Memorial’s Annual Reports, the last ten years of which are online. Before that, they are in bound copies of Parliamentary Papers, which are heavy lifting but well-indexed. Researching visitor statistics in these documents was problematic. In the 1990-91 report, we are told that annual visitor figures are approximately 750 000; in 1991-92 they are approximately 800 000. Yet, over the next few years, we have a run of figures precise to the last digit. Perhaps the Memorial purchased a new counter. Sometimes, figures are rounded, sometimes not, sometimes they are rounded on one page and precise on another. In one report, the figure varies by 45 000 from one reference to the next, simply because of a typographical error. Figures for one year are sometimes revised retrospectively – we have tried to use the higher figure in these cases – and sometimes visitors to the research centre and student visitors are counted separately – we have added them in to get a total figure. The total figures also include visitors to the Memorial’s Mitchell annex (the Treloar Technology Centre), constructed in recent years. Statistical issues about the Memorial’s website are dealt with in the text of this article.

[2] ‘Anzackery’ is the overblown, jingoistic, often commercialised version of Anzac. Use the Honest History website Search engine to find plenty of references.

Thanks Velodrome. We have drawn your comment to the attention of the folks at the Memorial.

I was looking at the latest annual report the other day after a moderately frustrating bike ride to the AWM to buy a book at the bookshop. The AWM isn’t exactly centrally located, so I thought the report might say something about how people actually get there. Nope, not that I could see.

The AWM does provide some places to chain one’s bike and I’d found the 2 locations on the website before I went. Just as well, because I saw no signs to indicate where they were. In fact, there just aren’t signs for bike riders anywhere. At the intersection of Anzac Pde and Constitution Ave a couple from Qld riding back from the AWM asked me for directions. No signs. (Note that motor traffic signs aren’t always useful for cyclists looking for bike paths. I told them how to make their way through a carpark/construction zone to a tunnel under Parkes Way.)

Anzac Pde is supposed to have a shared bike/pedestrian path. Well, yes, except that the various memorials along Anzac Pde make the side road a better proposition for cyclists.

I don’t think the AWM has given any serious thought to encouraging people to cycle to the Memorial. But doesn’t Canberra market the city to visitors as cycling friendly? My guess is that the AWM doesn’t really look beyond “visitations” by school kids on buses and senior Australians in cars.

Thanks, David, for a most interesting article, and particularly your observation that visitors to the Memorial as a proportion of the Australian population has not increased since the 1990s. That early 90s peak would have been related to a heightened interest in World War II generally as the 50th anniversaries of the various battles came up and also the return and burial of the Unknown Soldier in 1993. I was employed as a Research Officer at the AWM in 1995-6 and it was our proud boast then that we were the most visited museum in Australia (of course there was no National Museum then).

A couple of observations about the web site visits. I use it a lot because the AWM kindly permits me to use its images in University lectures and I do relatively often. I also visit it for information although material held at the AWM, although much of it is not yet digitised, so the web site can really only indicate what is held in the Research Centre. I would estimate that most site visitors are either researchers and teachers, potential museum visitors or people trying to find information about their service personnel relatives. Does the AWM count visitors to the Book Shop site separately, I wonder? It would also be interesting to see if any attempt has been made to link site visits to physical visits.

In the end, ofcourse, when an organisation is dependent on funding whether private or government, it will always put the best spin on its figures, so you can’t blame it for that. A museum without visitors is a museum without funds. How much the AWM fosters the belief that these figures are evidence of an increased interest in “Anzackery” is another question.