‘That diversity trumpet sounding louder: Australian Foreign Affairs, Meanjin, and the Australian Dictionary of Biography’, Honest History, 28 March 2019 updated

Update 12 April 2019: Henry Reynolds in this edition of Meanjin: now open access

The announcement of a grant of half a billion dollars to the Australian War Memorial for a massive program of extensions has reignited the long-smouldering controversy about frontier conflict. Despite criticism reaching back many years the memorial has steadfastly refused to admit Aboriginal warriors into the shrine, which director Brendan Nelson calls the soul of the nation.

Update 4 April 2019: new Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Mungo Man and Mungo Lady.

***

We like to note new editions of our leading quarterlies and we have also followed with interest the efforts of the Australian Dictionary of Biography to make its entries look more like the country whose history they help tell. So it was handy that the latest numbers of Australian Foreign Affairs (February 2019) and Meanjin (Autumn 2019), plus the special ADB edition of Inside Story (‘Recovered lives’, 8 March 2019) all lent themselves to a common theme, that of Australian diversity. It was also particularly apt that this theme emerged in the week when a lunatic, an unwelcome Australian export to Aotearoa New Zealand, committed his violent act against diversity in that country.

This issue of Australian Foreign Affairs asks what may seem a hoary old question – ‘Are we Asian yet? History vs Geography’ – but manages to come up with some interesting answers. Even a random dip finds this saucy one-liner from George Megalogenis: ‘The face our leaders present to the world – white, male, impatient and easily offended – is certainly not who we are as Australians’ (p. 71). Our diversity at home contrasts with the image of those whom we let represent us beyond our shores. As Megalogenis says, ‘1996 would prove to be the twilight of old Australia. The following year, the Asian-born population overtook the English-born for the first time in our history. By 2007, Howard’s final year in office, the Asian-born outnumbered the European-born’ (p. 73).

This issue of Australian Foreign Affairs asks what may seem a hoary old question – ‘Are we Asian yet? History vs Geography’ – but manages to come up with some interesting answers. Even a random dip finds this saucy one-liner from George Megalogenis: ‘The face our leaders present to the world – white, male, impatient and easily offended – is certainly not who we are as Australians’ (p. 71). Our diversity at home contrasts with the image of those whom we let represent us beyond our shores. As Megalogenis says, ‘1996 would prove to be the twilight of old Australia. The following year, the Asian-born population overtook the English-born for the first time in our history. By 2007, Howard’s final year in office, the Asian-born outnumbered the European-born’ (p. 73).

Attempting to answer that question ‘Are we Asian yet?’, Megalogenis ends with a summary of parts of our cities where we are Asian and parts where we are Anglo-European. He admits it’s complicated, though ‘our politics remains much whiter than the nation it serves’ (p. 69). He quotes figures for the non-European or Indigenous heritage of the Australian Parliament, six per cent, compared with 24 per cent for the country as a whole. Meanwhile, political parties continue to appeal to their ‘tribes’ – others would use the newishly popular term, ‘base’ – while all of them should be trying to build broader coalitions of new and old Australians.

Elsewhere in this number of Australian Foreign Affairs, David Walker, Linda Jaivin and Susan Teo ruminate on aspects of the question posed. Each of them deserves a close read, as do the reviews and correspondence section of the volume. After five issues, Australian Foreign Affairs manages to be both readable and weighty, and does it without footnotes or endnotes.

Kicking off from Megalogenis’s point about ethnic composition, this Meanjin is notable for the range of non-Anglo-Celtic surnames among its contributors – Aranjuez, Chua, Gandolfo, Hamad, Hedel, Ismail, Kronenberg, Micallef, Sakr – as well as lots of names that could have arrived with the First Fleet. Among the non-Anglo authors, Omar Sakr’s story demands attention. Sakr’s parents migrated here from Turkey and Lebanon but, at 29 years of age, he has no language other than English. ‘I’m a Casula boy, born and raised on Tharawal country.’ He tells how he decided to learn Arabic, ‘learning my first language as my second’.

Ruby Hamad riffs off The Lebs, a novel by Michael Mohammed Ahmad. She looks at what Anglo-Celtic reviewers thought of the book, which is about young men growing up in the Punchbowl area of Western Sydney. She describes an incident in the book which underlines how Anglo-Celts still fall back on caricature when dealing with Lebanese. Bani, working with ‘a troupe of white theatre performers’ is given a line to use in a performance: ‘You’re gonna say, “Aussies are the biggest sluts,” and the others are going to respond.’ Concludes Hamad: ‘You can take the Leb out of Punchbowl Boys, but you can’t take the Bad Arab out of the imagination of white Australia’.

Ruby Hamad riffs off The Lebs, a novel by Michael Mohammed Ahmad. She looks at what Anglo-Celtic reviewers thought of the book, which is about young men growing up in the Punchbowl area of Western Sydney. She describes an incident in the book which underlines how Anglo-Celts still fall back on caricature when dealing with Lebanese. Bani, working with ‘a troupe of white theatre performers’ is given a line to use in a performance: ‘You’re gonna say, “Aussies are the biggest sluts,” and the others are going to respond.’ Concludes Hamad: ‘You can take the Leb out of Punchbowl Boys, but you can’t take the Bad Arab out of the imagination of white Australia’.

The rest of this Meanjin ranges widely, as all of its issues do, from a detailed essay by Adolfo Aranjuez on gender identity and a fragment of memoir by Shu-Ling Chua, to reflections on classic Australian (or perhaps Melbourne) moments like the 1956 Olympics (this from a different angle, though), the West Gate Bridge disaster and some murders in Brunswick. There is also Greg Melleuish on what seems like a hackneyed issue but is always worth another look, whether the Liberal Party of Menzies has run its course. All in all, there’s enough reading here to keep one going till the next Meanjin.

Also on the reading list should be the joint venture between Inside Story and the ADB, ‘Recovered Lives’, which hits the diversity target from another direction, gender. It shows how little attention the early editors of the ADB, reflecting the mores of their time – the ADB was founded in 1966 – paid to women of note; fewer than four per cent of ADB entries for the colonial period are about women. (Even today only 12 per cent of total entries are about women.) The aim is to add 1500 new entries on women who were active before 1901.

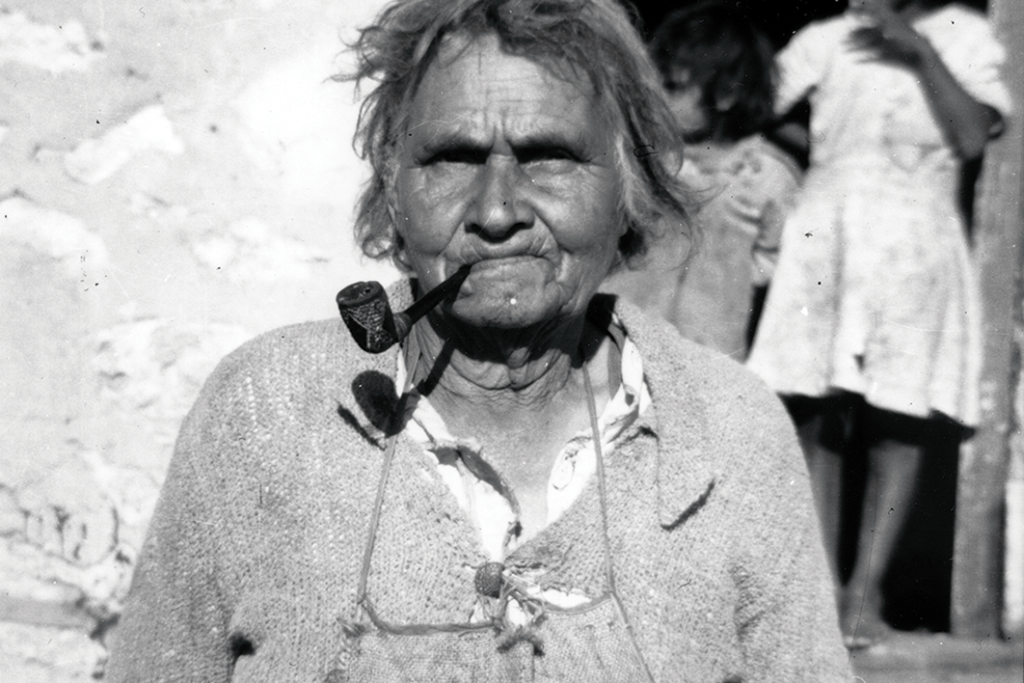

‘Recovered Lives’, across the 28 women covered by the 19 authors, achieves a particularly varied and interesting selection. Read about Ann Hordern, the driving force behind the emporium of that name, Iza Coghlan, one of the very few female medical students at the University of Sydney in the 1880s, Mathinna and Katipelvild Margaret ‘Pinkie’ Mack, Indigenous women in Tasmania and South Australia, the Gregory sisters, cricketers in a family of them, Lim Lee See, matriarch of Darwin’s Chinese community over many decades interrupted by World War II, ‘Chubbie’ Miller, pioneer ‘aviatrix, Roma Craze, secret contributor to the war effort at Bletchley Park.

‘Pinkie’ Mack 1943 (South Australian Museum)

‘Pinkie’ Mack 1943 (South Australian Museum)

So, diversity in at least two dimensions, ethnic and gender, is presented in these sources. (There’s locational diversity, too, in those Western Sydney and Melbourne pieces.) While considering ethnic diversity, though, we should be cautious about glib claims by politicians that Australia is the world’s greatest example of multiculturalism. Gwenda Tavan, in her chapter in The Honest History Book, points to the continuing neglect of our immigration history, which leads, in turn, to glossing over the gaps between the multicultural reality of our country and the continuing Anglo domination of its power structure.

The neglect of our immigration history is not benign. It feeds popular assumptions that only white, British settlers and the white native-born have contributed to the nation-building project; that only they have the cultural, social and political authority to define the nation’s values and identity. It leaves Australians vulnerable to scare campaigns about foreigners and the mistaken belief that immigration and ethnic diversity can be wished or legislated away (by abandoning multiculturalism, or banning Muslim immigration, or keeping refugees in our care in indefinite detention on remote islands). (p. 156)

Productions like the three noted here will help to gradually change the culture – by discussing openly aspects of our diversity as seen from many perspectives and by people with many names that are not obviously Anglo-Celtic, genders that are not only male, and with other characteristics that are not easily pigeon-holed and that lead to different outcomes. After all, an at times insidious and at times blatant presentation of an Anglo-Celtic, blokey Australia – Tavan refers to ‘a narrow Anglo-nativist view of Australia in which the so-called “Anzac legend” is central’ (p. 152) – has got us to where we are now. We have, as Marx and Engels almost said, nothing to lose but our chains. Though, come to think of it, and remembering that zinger from Ruby Hamad about Bad Arabs, perhaps Franklin Roosevelt’s ‘The only thing we have to fear is fear itself’ is even more apposite.

* David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and co-editor of The Honest History Book. He has written many pieces for Honest History which can be found using our Search engine or our author reference.