David Stephens*

‘Lest We Forget#4: Will today’s children have to go to war – and do we commemorate past wars in a way that makes them think they’ll have to?’ Honest History, 21 April 2022

The poet Osbert Sitwell (1892-1969) wrote this after he returned from World War I:

The Next War

The long war had ended.

Its miseries had grown faded.

Deaf men became difficult to talk to,

Heroes became bores.

Those alchemists

Who had converted blood into gold

Had grown elderly.

But they held a meeting,

Saying,

‘We think perhaps we ought

To put up tombs

Or erect altars

To those brave lads

Who were so willingly burnt,

Or blinded,

Or maimed,

Who lost all likeness to a living thing,

Or were blown to bleeding patches of flesh

For our sakes.

It would look well.

Or we might even educate the children.’But the richest of these wizards

Coughed gently;

And he said:’I have always been to the front

– In private enterprise -,

I yield in public spirit

To no man.

I think yours is a very good idea

– A capital idea –

And not too costly . . .

But it seems to me

That the cause for which we fought

Is again endangered.

What more fitting memorial for the fallen

Than that their children

Should fall for the same cause?’Rushing eagerly into the street,

The kindly old gentlemen cried

To the young:

‘Will you sacrifice

Through your lethargy

What your fathers died to gain ?

The world must be made safe for the young!’

And the children

Went. . . .

Sir Osbert Sitwell 1934 (National Portrait Gallery, London/Howard Coster)

Sir Osbert Sitwell 1934 (National Portrait Gallery, London/Howard Coster)

Sitwell’s poem is relevant to the way the Australian War Memorial presents war to children in this twenty-first century. ‘The Memorial does not glorify war’, we are regularly told. Of course, it doesn’t; only idiots do that. But it sanitises war for children and makes war seem an inevitable part of being Australian – or even being human. (One of the arguments for the current redevelopment program at the Memorial is that it will ‘future-proof’ the building – against the likelihood of having to commemorate the dead from wars still to come.)

James Rose wrote in Crikey in 2014 about how the War Memorial dealt with children at that time:

Despite an apparent endeavour to not celebrate victory, the War Memorial can be guilty of celebrating – or at least assuming the necessity of – the act of war itself. Parts of the memorial are like a fun park. You can [in the Memorial’s Discovery Zone] be in the trenches, in a navy ship’s bridge, and watch a spectacular Peter Jackson-produced short film about fighter pilots in WWI. It’s shamelessly loud, exciting, fun and gung-ho. It’s hard not to see it as a kind of imprinting … While victory is not directly exalted, it seems the message is that war can be ok. If you win. Even if you die and win you can find honour. Dead losers stay silent in their unmarked graves.

I wrote about the same subject in 2015:

T]he blandness of the presentation [‘Hands on History with the Memorial’s education team] reflected the War Memorial’s riding rules for talking to children. The short version of this is ‘age-appropriateness’. Depending on the age of the audience, this policy might justify not dwelling on the effects of bombing and it might mean presenting the death of aircrew as ‘did not come back’ rather than ‘incinerated’ or ‘riddled with anti-aircraft fire’ or ‘hosed out of the gun turret by ground crew on return to base’. But ‘age-appropriateness’ doesn’t excuse the one-sidedness of presentations like this. Casualty figures for Allied bomber aircrew are indeed horrendous. Nevertheless, developing a theme about the dangers of aircrew ‘jobs’, even to the extent of recognising that people can get killed doing them, without mentioning that many, many more people get killed on the ground, in circumstances that are just as horrible, is pulling an awfully big punch.

Two-up rules on the Memorial’s ‘Remembering with kids’ page (AWM)

Two-up rules on the Memorial’s ‘Remembering with kids’ page (AWM)

The Discovery Zone has closed permanently but the Memorial’s website resources for children hold the line until a replacement display is inaugurated as part of the Memorial’s big build. What there is on the website suggests the tradition of sanitisation will continue. There is a recipe for Anzac biscuits, a gunfire breakfast and bully beef, an ‘understanding Gallipoli’ module, the history and rules of two-up, highlights from classic Anzac Day football matches, Anzac Day themed origami, and photographs of family members wearing their war medals.

This stuff is far more bland than the outbursts of former Minister for the Centenary of Anzac, Senator Michael Ronaldson, whose remarks about children and blood sacrifice were frankly quite weird. For example, in his speech to New South Wales Legacy in 2014:

They will be carrying the torch and that is the next generation of young Australians … And when they hop on a school bus, or they walk home, or they go shopping, or they go out at night with relative freedom – that they realise in many instances that freedom has been paid for in blood. And they must understand that … And if our young men and women understand that, ladies and gentlemen, then our young men and women will take up the cudgel and carry that to ensure that we never, ever, ever, forget.

‘This rhetoric’, I wrote in 2015, ‘effectively conditions the next generation for military endeavours involving blood sacrifice. That’s our legacy to our children and grandchildren: the expectation that honouring the war dead of the past – carrying the torch – requires the preparedness to become the war dead of the future.’

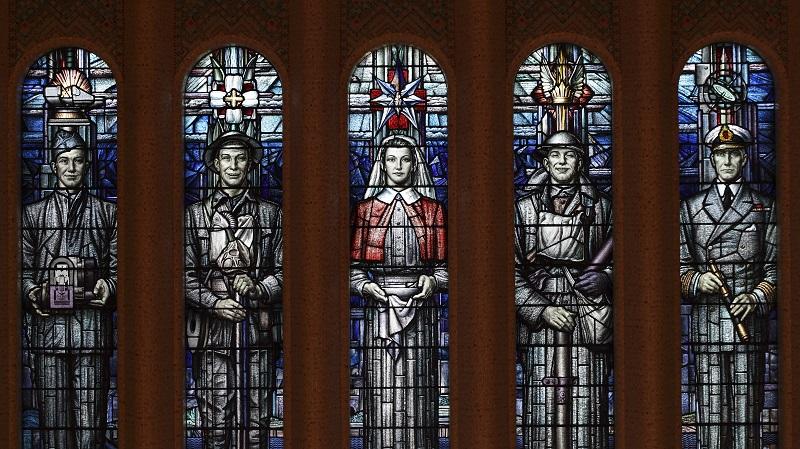

Then, when Brendan Nelson was Director of the Australian War Memorial, he often referred to the fifteen values depicted in the Napier Waller windows above the tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier: resource; candour; devotion; curiosity; independence; comradeship; ancestry; patriotism; chivalry; loyalty; coolness; control; audacity; endurance; decision. ‘Young Australians seeking values for the world they want need look no further than these’, Dr Nelson said. Really? Do children really need to visit the Memorial to find life guidance? Surely they can find these values displayed, not just by people in military uniforms depicted on stained glass in the Hall of Memory, but by first responders, volunteer firefighters, police, nurses, teachers, ministers of religion, and other role models? By boys and girls who join Australian Scouts and sign up to a Law and Promise containing similar words? Or even just by anyone with a conscience and a calling?

Napier Waller windows in the Hall of Memory, Australian War Memorial (AWM)

Napier Waller windows in the Hall of Memory, Australian War Memorial (AWM)

All in all, it is not surprising that historian Anna Clark, talking to 15 year-olds in 2008, was surprised by the number of students who assumed a ‘militarised national identity’ was ‘intrinsically Australian’. What would Clark find if she asked the same questions in 2022? There have been a lot of Anzac Days since 2008, a lot of visits to the War Memorial, a lot of Department of Veterans’ Affairs showbags unpacked in schools. Do the children believe it all? Do they see a khaki future? It’s an important question; Lest We Forget that the wars of the future will be fought by the children of today.

*David Stephens is editor of the Honest History website and was co-editor with Alison Broinowski of The Honest History Book.