We presented these items in our e-Newsletter no. 28 earlier in the month on the 70th anniversary of Hiroshima-Nagasaki (and the 100th anniversary of Lone Pine). We wanted to run them through again.

Also, given today’s 49th anniversary of Long Tan, it is worth drawing attention again to our package on the subtleties of the memory of the Vietnam War. There were hints in parliamentary remarks today that a received view of the war and its aftermath was still common.

To subscribe to our e-Newsletter and other updates readers should visit our home page.

80AD, Britain. ‘Our horsemen kept pursuing them, wounding some, making prisoners of others, and then killing them as new enemies appeared … Equipment, bodies, and mangled limbs lay all around on the bloodstained earth … The pursuit went on till night fell and our soldiers were tired of killing … For the victors it was a night of rejoicing over their triumph and their booty. The Britons dispersed, men and women wailing together, as they carried away their wounded or called to the survivors.’ (Tacitus, Agricola, written c. 98AD, translated H. Mattingly)

1862, Texas. ‘On going round on that battlefield with a candle searching for my friends I could hear on all sides the dreadful groans of the wounded and their heart piercing cries for water and assistance. Friends and foes all together … Oh, the awful scene witnessed on the battle field. May I never see any more such in life.’ (AN Erskine, Confederate soldier, after the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, in Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb, 1943)

1915, Lone Pine. ‘On the first hill I bayoneted a Turk who was feigning death, with a few extra thrusts. He was an oldish man & on the first thrust which did not go right home he tried to get his revolver out at me, but failed … Poor Tippen got shot just in front of their trench in the stomach with two bullets, he died groaning horribly. I killed his assailant however by giving him five rounds in the head. I … let him have it full in the face. It was unrecognisable.’ (HM Jackson, 13 Bn, in Bill Gammage, The Broken Years, 1975)

Europe, 1945. ‘Convinced that these three Germans were a mere patrol and that there were no others nearby, we went forward to look at the one I’d killed two hundred yards away, exactly as if we were hunters going up to inspect the game we’d shot. The dead one was a large NCO, hit about five times, three times in the head, which was bleeding copiously. “Stuck pig” would suggest the appropriate image. He stared at me with dead, as if reproachful eyes, as I removed his papers from his pocket. I’d won because I was faster than he.’ (Paul Fussell, Doing Battle, 1996)

New Mexico, 1945. ‘The Atomic Age began at exactly 5:30 Mountain War Time on the morning of July 15, 1945, on a stretch of semi-desert land about five airline miles from Alamogordo, New Mexico. And just at that instance there rose from the bowels of the earth a light not of this world, the light of many suns in one.’ (William Laurence, New York Times, 26 September 1945)

Hiroshima, 1945. ‘We were lying and talking to each other and wondering how long we could survive. But gradually they became quiet. By the next morning I was the only one alive, all my other classmates died. Each time somebody died, they carried the person on the straw mat out of the room and took them to the centre of the playground and cremated them. They put a bunch of the dead bodies together and then they were continuously cremating.’ (Hiroshima survivor, Tomiko Matsumoto)

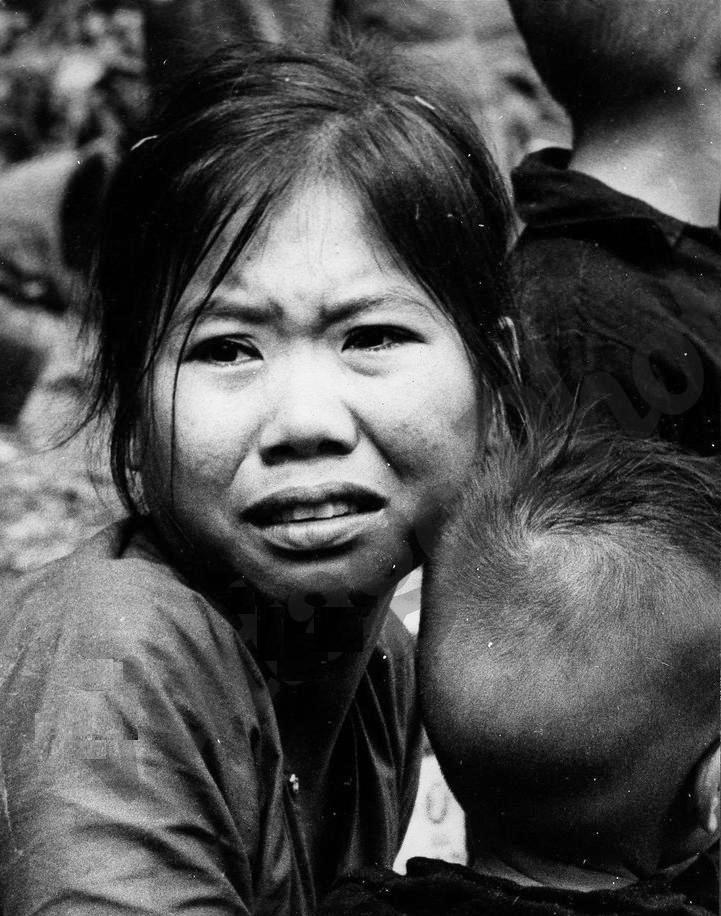

Vietnam, 1968. ‘A little girl was lying on the table, looking with wide dry eyes at the wall. Her left leg was gone, and a sharp piece of bone about six inches long extended from the exposed stump. The leg itself was on the floor, half wrapped in a piece of paper.’ (Michael Herr, Dispatches, 1977)

Drone ‘warfare’, today. ‘”You could see these little figures scurrying and the explosion going off and when the smoke cleared, there was just rubble and charred stuff.” This figurative reduction of human targets helps to make the homicide easier: “There’s no flesh on your monitor, just coordinates”. One is never spattered by the adversary’s blood. No doubt the absense of any physical soiling corresponds to loss of a sense of moral soiling.’ (Former CIA drone operators in Grégoire Chamayou, Drone Theory, translated J. Lloyd, 2015)

Good investments. ‘[Northrop Grumman, Raytheon and BAE Systems] are major players in the military-electronics market. The companies are experiencing strong demand for electronic-warfare equipment, high-performance sensors, tactical communications gear, and other technology that benefits from the digital revolution. BAE Systems is especially well-positioned in this business area because it builds the electronic-warfare suite for the tri-service F-35 fighter, by far the biggest tactical aircraft program in the world. That program will provide a steady stream of revenues to both the U.S. and British parts of BAE for decades to come.’ (Loren Thompson, Forbes, 30 July 2015)

Word from the sponsors. BAE (see previous item) also makes systems for drones. According to the Defence Department’s ‘Team Australia’ website, BAE Systems Australia is Australia’s largest defence company. Australia has committed to the F-35 at a cost of $A12.4 billion. The Australian War Memorial’s theatrette is the BAE Systems Theatre. BAE and Raytheon are corporate sponsors of the Memorial and Northrop Grumman held a party in the Memorial’s Anzac Hall.

18 August 2015

Piper’s Lament, Long Tan, 18 August 1969 (Australian War Memorial EKN/69/0085/VN/CJ Bellis)

Piper’s Lament, Long Tan, 18 August 1969 (Australian War Memorial EKN/69/0085/VN/CJ Bellis)

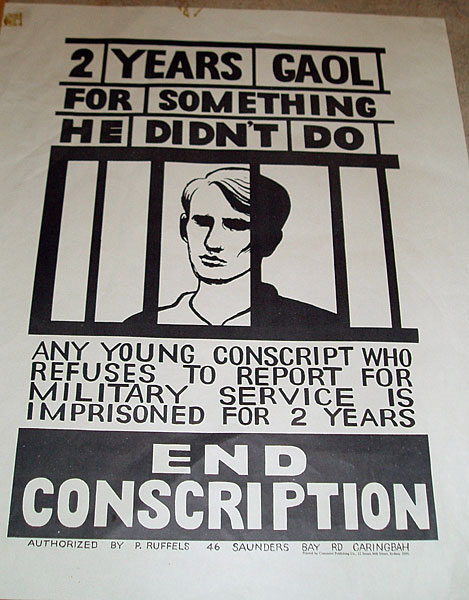

Histclo; Australia and the Vietnam War

Histclo; Australia and the Vietnam War

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.