‘Prime ministerial exits: an interview with Norman Abjorensen’, Honest History, 24 February 2014 (updated)

Norman Abjorensen is a Visiting Fellow in the Policy and Governance Program in the Crawford School at the Australian National University. He is a prominent media commentator on Australian politics, a former senior journalist, has written a book on Australian political parties and held overseas academic positions.

Dr Abjorensen is now writing a book on Australian prime ministerial exits, the ways in which they left office. The book’s working title is The Manner of Their Going: Prime Ministerial Exits in Australia. Dr Abjorensen argues that ‘to look at how power is lost or relinquished is to be reminded of all that is transient… It can highlight both the heroic side of human nature as well as illuminate its more fragile aspects; it can chart the journey from the dizzying heights of command to the lonely depths of defeat.’

Honest History (represented by David Stephens) interviewed Dr Abjorensen on 19 February 2014. A draft of his chapter on the exit of the first Prime Minister, Sir Edmund Barton, is here: 193 Abjorensen Edmund Barton_Chapter. An article by Dr Abjorensen from February 2015.

Alfred Deakin

HH: What led you to write a book about prime ministerial exits?

NA: Four years ago I was made a Fellow at the Prime Minister’s Centre at the Museum of Australian Democracy and I got a research grant to write a political study of Alfred Deakin and I was particularly interested in the way Deakin’s political world had collapsed by the time he left politics.

HH: And personal world, too, to some extent?

NA: Very much so; the inner life reflected the outer reality. The starting point for this was Dangerfield’s great study, The Strange Death of Liberal England, and I started thinking, and re-reading that. It had been a very influential book since my undergraduate days. I started reading this with Deakin very much in mind, how his liberal conception of the world had started to disintegrate. So the research project I put up for the fellowship was based on the strange political death of Alfred Deakin. (A paper on this subject is here.) The idea was to write an entire book about Deakin. I’ve done most of the research for the book but haven’t written it; Deakin started to irritate me. The more I delved into Deakin…

HH: He seems very pious.

NA: Yes. I found him an insufferable prig. I said to David Day once, “I’m having difficulty with this: I’m writing a political biography of someone I really don’t like”. He said, “You’re writing about the wrong person. I really have to like the people I’m writing about.”

Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, looking north from Flinders Street, c. 1900 (source: Flickr Commons/State Library of Victoria 10381/57347)

So, our received version of Deakin is “Affable Alfred” but I’m much more inclined to the view of “Devious Deakin”. He sold out every principle he had, he sold out most of his supporters and his friends and, certainly by the time he left politics, everything he’d stood for had either been compromised, had been abandoned or had been left behind. So, I’d done the research on Deakin and I thought, I’ve seen the way he left politics, this is waiting to be written, let’s look at some more people of that period. I looked at Barton, Reid, Watson, Fisher. At that stage, I think we’d had 26 prime ministers, now we’ve got 28, so I thought this is starting to fall into a pattern of something much larger.

Types of prime ministerial exits

HH: What types of exits are there, given what you’ve seen from the number you’ve looked at so far? Are there categories of exits or are they all much the same?

NA: They are all very different. I paraphrase Tolstoy here: “Most prime ministers in office are very similar but they all left office in very peculiar and unique circumstances”. If we go back to Richard II – “For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings” – the way they all lost office is fascinating, some by the electorate, three unfortunately by death, or on the floor of the House. Increasingly, we’re seeing parties actually determining who’s going to be prime minister. There’s a series of personal and professional failures, lack of confidence, losing trust, every case is different.

That might sound a fairly trite thing to say, but the thing about the prime ministership is that very few people leave it voluntarily; they cling to it; they’d do anything to stay in office. I think the only unambiguous voluntary departure was Menzies; he probably even stayed too late. There is some doubt about whether Barton jumped or was pushed. Fisher was being breathed down the neck of by Hughes and his own party and he was tired. They might have preferred to stay there. Very few of them have left office willingly. We’ve got this tension about trying to cling to office, the forces that are against you, how you overcome them, how you keep the confidence of the electorate, of your own party, the promises you’ve made. All of these things are all little dramatic interludes.

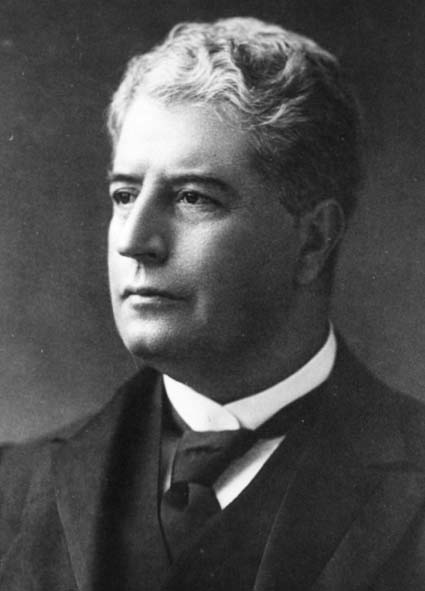

Sir Edmund Barton 1901 (source: National Archives of Australia A5954, 4240551)

HH: Is there a bit of Lord Acton in there, that they’ve been corrupted by being in power, or drugged by being in power and that they don’t like getting away from that power trip?

NA: I think it becomes very addictive. Notice the change in politics, too, because the hunger for office is probably much more acute now than it was.

HH: There’s less altruism driving politicians now?

NA: Yes, we go back to the likes of Curtin, a very unwilling leader in 1935. “Do I want this job?” “Am I up to it?” “I am the servant of the party.” Chifley, to a very large extent, didn’t go out of his way to win the prime ministership: “it’s what the party wants”. (Evatt certainly wanted it.) And in more recent times we’ve got Andrew Peacock and that very telling interview he gave about not being sure he ever wanted to be prime minister. There’s probably another book in pretenders and contenders.

Edmund Barton leaves the job

HH: What particularly stuck in your mind about the story of Edmund Barton leaving the job?

NA: I think it was a very uncomfortable time in office. He’d never set out to become the leader. He was drafted into office, he was pushed into office. I’m still debating whether to write a chapter about the prime minister who never was, Lyne. We’ve still got Deakin’s received version of the Hopetoun Blunder. I still cling to the view that probably protocol dictated that he had to ask the Premier of the mother colony. I think [Joseph] Chamberlain, who was the Colonial Secretary at the time, sent him an urgent telegram: “Please explain why you’ve asked Lyne”.

Lyne would have made a good prime minister. In fact, he was one of the great reforming figures of that first decade. He wanted to be prime minister. Deakin certainly didn’t want the job. Barton was reluctantly conscripted into it. He’d never been premier of a state; he was presiding over a Cabinet of former premiers. I don’t think he had the temperament. There was a lot of administrative machinery. He started off with four public servants at his disposal, the statute book was blank and he wasn’t the administrative type. Certainly, reading those early accounts and some of the papers, it was a very uncomfortable time for Barton. He would have liked the job on the High Court. But then again, there were parts of the prime ministership – the pomp, the ceremony, the entertainment – that he liked.

HH: Was he “past it” when he got the job?

NA: Probably; his best days were behind him. I certainly think the energies he put into the Federation movement had exhausted him. He didn’t have that “go”, that spark. There was very time-consuming travelling around the country, certain personal financial insecurity at the time. Certainly, in a legislative sense, Deakin was the driving force in that first government.

HH: If Henry Parkes had been 15 years younger (and still alive) would he have been a lay-down misere for the job or not?

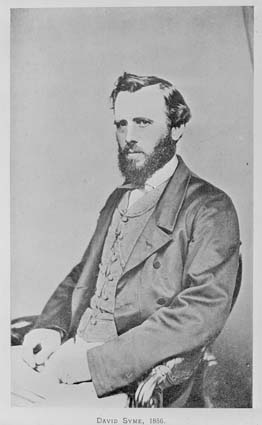

NA: Probably. If George Reid had retained office in New South Wales in 1899, would he have been a contender? He was, among that first group of politicians, our first four prime ministers, he was the only one who really wanted the job. (Reid falls into my category of “accidental” prime ministers, along with Watson, Page, Fadden, McEwen, Forde.) The “king-maker” in that first decade was Alfred Deakin: anyone held office because of Deakin’s whim at the time. He persuaded Barton to stand at the instigation of David Syme, a very powerful figure behind the scenes there.

David Syme’s political influence

HH: Was David Syme the Rubert Murdoch of that era or is that too simplistic?

NA: In a sense, in the way that he wielded his political power, “Yes”. I think he was far more principled than Rupert Murdoch has ever been or ever will be. Syme was the great driving force behind Protectionism. When he bought the Age with his brother he started writing editorials about Protectionism. He was a lone voice. He not only convinced the political elite, he convinced a vast proportion of the population that Protectionism was the way to go, to keep some of the gold money in Victoria, to protect social order. He built up a huge movement. Now he was, of course, the patron of Deakin. He got Deakin to run in state politics, he supported him, he gave him a job at the Age.

David Syme, a portrait from 1856, only four years after he arrived in Australia and when he was just 29 years old (source: National Archives of Australia A1200, 11874618). Pictures of Syme seem to be rare, though a painted portrait from around 1892 is here.

When the prospect of Lyne becoming prime minister was transmitted to Syme, he was apoplectic because Lyne, while not a Free Trader, didn’t have the zeal in the areas that Syme thought were necessary. So Syme was firing off telegrams, expressing his disappointment, urging all the premiers, certainly urging Deakin to push Barton up for the job. So, there was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing going on, certainly, with the various manoeuvres, with Deakin putting up Reid, taking out Reid, putting up Watson, taking out Watson, all of it with an element of Syme. They [Deakin and Syme] didn’t always see eye to eye, in fact, they fell out. But Syme was an extraordinarily powerful influence in those early years of the Commonwealth.

HH: How revealing are the archives and the records on this period? Can you track through a lot of this influence of Syme, for example?

NA: He was in very close touch with Deakin. Their relationship went back decades. There were a lot of private conversations and private meetings. We’ll never know what took place at some of them – although some of them were recorded – but there was a lot more going on than we actually know about. One can fairly safely assume that Deakin didn’t disregard Syme’s advice lightly. He didn’t always take it but it would have been factored in very heavily into his thinking, his decision-making process.

Prime ministers and governors-general

HH: You mentioned in the chapter on Barton, tensions between Barton’s government and both of the first two governors-general, Hopetoun and Tennyson. Were these to do with personalities on both sides or still some uncertainty about the nature of the relationship between PM and governor-general?

NA: I think both of those. The governor-general’s role was still evolving. The Governor-General was getting a constant stream of instructions from London, from Whitehall. The Colonial Office was not short on sending out advice. The Governor-General was, in fact, Britain’s man in Australia; he was the notional Head of State but also reporting back and looking after British interests.

HH: I was reading about Munro Ferguson as Governor-General in 1914. People like him who had had a significant political career in Britain presumably knew about ways of manipulating activity that some of the more recent governors-general were not across so much.

NA: Yes, the governors-general with political experience tended to be a little more hard-headed and pragmatic. In that first decade, the Governor-General was immensely powerful. If you read the Constitution now, they’re still powerful but practically it is a far more symbolic role – 1975 aside – but the constant shifting allegiances in Parliament, the requests for double dissolutions or early dissolutions were turned down. The Governor-General in that first decade of the Commonwealth played a pivotal role and there were certainly tensions between the early prime ministers and both of those early governors-general.

HH: Some of the early governors-general have been characterised as “chinless wonders” and “younger sons of younger sons”. They were a bit more significant than that, some of these men?

NA: Yes. While they were feeling their role as governor-general they were also conscious that the Commonwealth Parliament itself was new, that the Commonwealth’s politicians were dealing with something without precedent, without a history. It was a two-way process: you actually had two powerful institutions really feeling their way in a dark room, bumping into each other occasionally.

Barton Ministry, c. August-September 1903. Left to right (standing): Senator James George Drake, Senator Richard Edward O’Connor, the Hon. Sir Philip Oakley Fysh, the Hon. Charles Cameron Kingston, the Hon. Sir John Forrest. Seated: the Hon. Sir William John Lyne, the Rt Hon. Edmund Barton, Governor-General Lord Tennyson, the Hon. Alfred Deakin, the Hon. Sir George Turner (source: National Archives of Australia, A1200, 11217519). Alert Canberra readers will notice that every minister in the picture has a Canberra suburb named after him – except Drake who was briefly (August-September 1903) Minister for Defence until Barton resigned on 24 September. This dates the picture; the Archives caption says both 1902-03 and 1902.

Feelings after leaving the job

HH: We mentioned before briefly about people leaving the job, but what insights have you gained about how incumbent prime ministers feel after they leave the job? Is it regret, or relief or something altogether different?

NA: It varies immensely. Memoirs aren’t all that enlightening: I looked in vain in Bob Hawke’s memoirs to see what he really felt about it; I talked to him about it; I know what he really thinks but it didn’t find its way into print. There’s probably an interesting study waiting to be done about post-prime ministerial careers. We’re getting now to a stage where prime ministers leave much earlier than they did. They don’t die in office very often, they don’t stay in the job into their dotage like Menzies did. John Gorton went out and did a whisky commercial. People like Watson went into business, very successfully. Bruce went about his own business career, became a member of the House of Lords. Gough Whitlam really was unique in many ways: he became the first Prime Minister Emeritus; most of his post-prime ministerial career was spent elaborating on and justifying his term in office – very effectively.

Fisher and Hughes

HH: Are there any instances where you think history might have been different had the incumbent stuck around, for example, Fisher and Hughes. If Fisher had stayed and been well and committed would things have been different? Or was Fisher on the same track as Hughes?

NA: The British connection was all important in the First World War and that really divided them and you had that division in the Labor Party between the Irish Catholic side and the British, largely Protestant side. The war was for the Empire, passions ran high on both sides, you had the intervention of Mannix saying that, in his view, shared by many Irish Catholics in the Labor Party, that Belgium had not been wronged as much by Germany as Ireland had by England. These were high tensions. I suspect Fisher would have been a far more conciliatory figure than Hughes, the Labor Party might not have split, but then again there wasn’t a deep difference between Hughes and Fisher on the war – remember that quote of Fisher’s “to the last man and the last shilling”.

HH: I read something very similar said by I think the Leader of the Opposition in WA. There must have been a sort of template at that time for remarks like that.

Scullin

NA: Talking of counterfactuals, look at the Scullin Government, where Theodore might have become Prime Minister. Things might have been different. Theodore anticipated Keynesian economics, he was ahead of his time, brought down by a Royal Commission… You asked before about whether anyone has been relieved when they’ve left the job. Many years ago, I had a long series of interviews with Frank Forde. His memory wasn’t great but there were things that stuck in his mind. I wanted to talk to him about his experience during the Second World War but he was much more inclined to talk about his experiences during the Scullin Government as Minister for Trade and Customs. He said that was the unhappiest time of his life: it was just day after day of bad news. He said he’d never seen a man so burdened in office as Jim Scullin and so glad to leave. He said Scullin seemed to have a spring in his step when he was relieved of the prime ministership.

HH: Scullin became quite a significant figure in the Curtin and Chifley Governments?

NA: Yes, there are myths about Scullin being the eminence grise, the great adviser. I did an interview 25 years ago with Nelson Lemmon, the last surviving member of the Chifley Cabinet, again, someone who could have been Labor Party leader. He said to me in the course of that, that there was a big myth grown up around Scullin. Certainly, he offered advice all the time, but he was a mischief-maker, an intriguer, a nuisance. He had nothing else to do. He’d stayed far beyond his usefulness. The myths do grow up around people. Of course, prime ministers don’t stick around any more. I think since Malcolm Fraser went you lose office, you go, you pack up and go.

Recent years

HH: How do our most recent prime ministerial exits stack up in terms of drama and pathos? Howard, Rudd, Gillard; all different again. But did the earlier exits get such a grip on the public as these exits did and be reworked after the event as much?

NA: I think the relationship with the public has changed. Certainly, with the advent of television, now of social media. Prime ministers were fairly remote figures. You read about them in the paper in the first decades of the Commonwealth. From the 1920s onwards you saw them in the occasional newsreel. To actually see a Prime Minister in the flesh you would have to go to a public meeting. There wasn’t that same interaction. You certainly didn’t have the distraction of opinion polls, the distraction of a constant 24 hour media cycle, so that relationship with the public was very different.

The whole game has changed now and what we are seeing in recent years – we’ve had five changes of prime minister due to parties – the big picture that emerges is the primacy of the political party in the Australian political system. It became quite clear to me during Rudd’s first term that he’d lost sight of his immediate and most important constituency, his own party. He thought he could govern without that and, of course, the party exercised its muscle, not the Parliament, not the electorate. It did the same to remove Gillard. Then, of course, we go back before that to Hawke and Keating, when Gorton was deposed, when Menzies was deposed, back to 1922 with Billy Hughes – was he deposed or did he jump? Well, they wouldn’t have formed government if he had hung onto the leadership.

HH: Then, Howard becomes one of a category of two – the ones to lose their own seat when their government loses – which he seems to have adjusted to reasonably well.

NA: Following in Bruce’s footsteps. There’s a longer-term issue here, which is a big gap in political science: why do governments die? What is it that happens to a long-term government, that’s been able to win several elections, does it lose impetus, does it lose strength, is there an aging process?

HH: “People have stopped listening” was the mantra attached to the Gillard Government’s decline.

NA: Yes. Politics is far more unforgiving than it was. The unfortunate Bert Evatt had four goes at winning elections and failed. Arthur Calwell, who might have made a very interesting Prime Minister in some ways, had suffered this overwhelming defeat in 1966, the biggest landslide Labor had suffered against it, and he wanted to hang onto the job. “Bert Evatt had four goes; I deserve one more go.” You’re probably not going to survive one election loss these days.

Mr Arthur Calwell at home, 1947 (source: National Archives of Australia A1200, 11211503; photo: Cliff Botttomley, Australian News and Information Bureau)

Change the PM and change the country

NA: Paul Keating said if you change the government you change Australia. I think further if you change the prime minister you change Australia. A prime minister of the same party, the same political persuasion can hare off in an entirely different direction. Look at the changes that Harold Holt wrought after succeeding Menzies, suddenly doing something about White Australia, something about reaching out to Asia, these were things that you couldn’t talk about during Menzies’ time. Keating did the same thing: he re-energised the government, took on things that Bob Hawke wasn’t interested in or didn’t have the inclination to pursue. Who holds the top job is important, they become a focal point for policy change, for identification, for the whole evolving image of Australian nationalism.