Michael Piggott*

‘What are we to make of Edmund Barton, our first prime minister? An exhibition in Canberra’, Honest History, 4 January 2021

Michael Piggott reviews an exhibition at Parliament House, Canberra: ‘Edmund Barton: Australia’s first Prime Minister’. The exhibition runs from 27 November to 14 February.

If an exhibition makes you think, it is already a success. And this one, presenting Barton’s life and times to acknowledge the centenary of his death, did that. The thoughts were almost entirely positive.

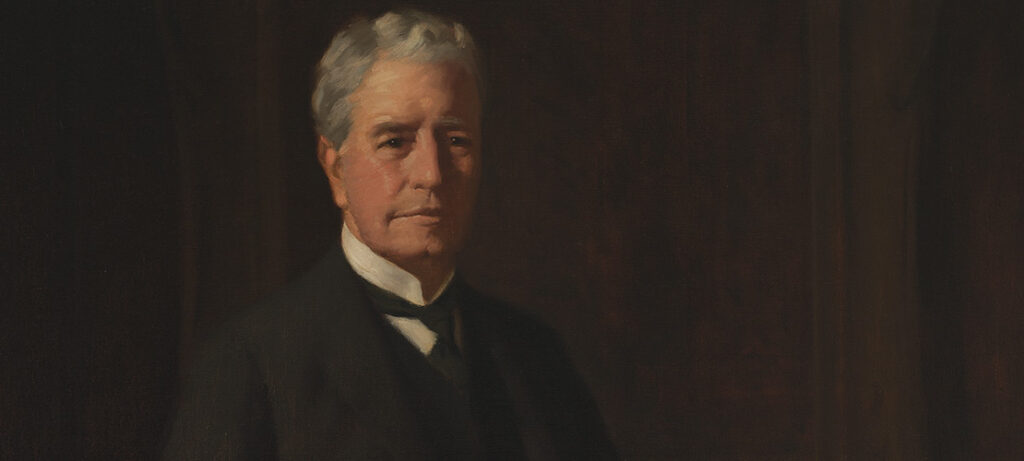

Norman Carter (1875-1963) The Rt Hon. Sir Edmund Barton GCMG KC (detail), 1913. Oil on Canvas. Historic Memorials Collection, Parliament House Art Collection

Norman Carter (1875-1963) The Rt Hon. Sir Edmund Barton GCMG KC (detail), 1913. Oil on Canvas. Historic Memorials Collection, Parliament House Art Collection

The exhibition has been installed in the Presiding Officers Exhibition Area, Level 1, Parliament House, although there is additional material in two small display cases in the main ground floor entrance hall. The show itself is also a sum of parts. Inside a partially enclosed gallery area are wall panels and display cases presenting the big themes of Barton’s life and career, dominated by his role in the federation campaigns of the 1890s, his leadership of the new nation’s first government (1901-1903) and his membership of the High Court (1903-1920). On the external walls of this gallery are large visual items, including a sequence of Bulletin cartoons, all representing moments in Barton’s career, an audio-visual presentation, and a selfie booth. Nearby, along the wall of the Great Hall, are other items and a timeline setting key dates in Barton’s life in national and international context.

In the lead-up to the centenary of federation, the percentage of Australians who could name our first PM was estimated at under 20 per cent, triggering an advertising campaign with the tagline ,‘What kind of country would forget the name of its first prime minister?’ This exhibition provides all the basic details explaining who Barton was and why his historical standing is so high, beyond the automatic status of being our first PM. Still, even presuming we are better informed now, I suspect the information conveyed is still needed, and one must hope many of the three-quarters of a million annual visitors to Parliament House will see it. And school groups too, even though the exhibition ends (for some reason) in mid-February 2021.

This important educative role aside, for me two aspects of the exhibition were noteworthy: the richness of the content and the way this was combined and presented. The designer, Sarah Evans of The Freelance Project, used proportion, materials, fonts and typographical ornaments to impressive effect. The result evoked both a scale befitting the ambition of federation and large open-air and interior gatherings, and the feel of an arts and crafts Edwardian era immediate yet remote.

The curator, Dr Anne Sanders, drew original material from nine different collections. The obvious sources included Parliament House’s own art collection, the Museum of Australian Democracy, the National Archives and the National Library (of which the latter two institutions between them hold many of Barton’s personal papers). But these sources Dr Sanders complemented by unexpected gems from Sydney Grammar School, the High Court, the Powerhouse Museum, the State Library of NSW and the National Portrait Gallery.

Dr Sanders has deployed all possible formats, too. There is plenty of visual content – representations, caricatures and, to use the language of those behind the creation of Parliament’s Historic Memorials Collection, ‘likenesses’ – but also important group photos relevant to the progress to federation and the large public crowds that marked the new Commonwealth (in Centennial Park, Sydney) and the new Parliament (Exhibition Building, Melbourne). One panel, by Swiss Studios, Melbourne, over two metres square and presenting photo portraits of all members of the First Commonwealth Parliament, is rarely displayed and is one of the few such records of its kind.

Australia: Sir Edmund Barton (image plate from Vanity Fair), 1902, Sir Leslie Ward (National Portrait Gallery, Canberra)

Australia: Sir Edmund Barton (image plate from Vanity Fair), 1902, Sir Leslie Ward (National Portrait Gallery, Canberra)

Before leaving the exhibition itself, here’s a small irritation. When curators include any kind of volume in a display case, they decide whether the internal content is worth sharing with the visitor. Open or closed? Open means the space needed is doubled, and light levels and the right page in terms of legibility and relevance weighed-up. Closed relies on the caption unless one wants to feature something more physical, such as a fine binding or a bullet hole.

Sanders presented the Commonwealth Law Review 1919–1920 closed. Apparently, this volume begins with some nice memorials to Barton as a High Court judge, but just being told that probably was enough. His first High Court notebook was also closed, however. Apparently, it begins with a reference to the investiture of the court on 6 October 1903, while the last entry refers to the controversial 1904 Pedder v D’Emden case. Why not share the handwriting and a page which linked to the caption information?

By contrast, Barton’s Sydney Grammar School text, Virgil’s Aeneid in Latin, was indeed opened (at a page with annotations and doodles). Its inclusion was accompanied by a gold medallion presented by Pope Leo XIII, following a meeting in 1902 when Barton and the pontiff chatted away in Latin, to the scandal of Sydney’s Protestants. It was an inspired inclusion. Barton graduated as a BA (Classics) from the University of Sydney in 1868 and his facility with Latin was directly relevant to various aspects of his career, as the textbook caption and his biographer Geoffrey Bolton make clear. I’d loved to have been able to read that page, not least as I had to do Latin and the Aeneid at school. Was the page or at least the doodles meant to be read by visitors? It was presented on the floor of a reasonably deep display case and my average height and eyesight made that impossible. It might as well have been closed.

***

Beyond the exhibition itself and the familiar accolades and automatic status which being first brings, what are we to make of Barton? On leaving the exhibition, I wondered where Barton sits within the Australian cultural and political imagination? Which Australia aligns with him emotionally the way Menzies and Howard are championed by certain opinion on the right and Hawke and Keating are so affectionally regarded on the centre left? Which town has embraced him in the way Bathurst owns Chifley and Devonport Joe and Enid Lyons? Which university has a Barton Prime Ministerial Library as do Deakin and Curtin?

Barton’s achievements, character and qualities allow him to be seen as acceptable across traditional divides. His central part in the federation movement is unassailable and, of federation itself, historical opinion from John Hirst to Marilyn Lake agrees it should stand above Anzac. Politically, too, there has been unity. In Sydney in March 1982, Malcolm Fraser delivered the inaugural Edmund Barton Memorial Lecture, ‘The strength of Liberalism’.[1] In Newcastle in July 2008, the ALP member for Hunter, Joel Fitzgibbon, delivered another inaugural Edmund Barton Lecture, ‘New thinking for a new century: building on the Barton legacy’.[2]

Unsurprising then that, reading about Barton’s real skill in influencing the federation outcome and steering decisions through Cabinet and bills through Parliament, a strong parallel emerges with Bob Hawke. Barton’s private secretary, Thomas Bavin, recalled his former boss’s ‘capacity for attracting personal affection and trust such as few men possess’, terms also used about Hawke.[3] Both these men were patient negotiators with a superb capacity to achieve consensus and broker compromises, yet still able to show stubbornness and steel. Both enjoyed legal associations: one was a barrister and justice, the other had a law degree and worked as an industrial advocate. Both liked a drink only to become teetotallers, they shared interests in cricket and fishing, attracted nicknames (Toby Tosspot and the Silver Bodgie), and suffered on occasion from depression.

Barton as a younger man (State Library of NSW)

Barton as a younger man (State Library of NSW)

A final reflection. The Barton exhibition is being presented at a time of strong debate about the role of museums in Australia and internationally. The questioning of public statues is also part of it, as is the movement to ‘de-colonise’ collections through restitution of material and more honest self-awareness of preconceptions. Reviewing Dan Hicks’ book, The Brutish Museum. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, recently in The Guardian, Charlotte Lydia Riley contrasted museums’ educational and other civic roles with a more critical view:

Dan Hicks sees it differently. In his beautifully written, carefully argued book, museums house unending violence, ceaseless trauma, colonial crimes committed again every morning as the strip lights click on. Museums are battlegrounds. [4]

A long way from Parliament House at the end of 2020, you’d think? Let’s first recall Thomas Mann’s observation in The Magic Mountain that ‘A man lives not only his own personal life, as an individual, but also, consciously or unconsciously, the life of his epoch and his contemporaries’, then note the span of Barton’s life and times, 1849-1920. Of course, this period saw considerable change – economic and social, the great strikes of the 1890s, and again we can note the federation movement. But there was also blackbirding, anti-Chinese violence, colonial participation in imperial wars (the Sudan 1885 and the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902), the annexation of Papua and continuing killing of Indigenous Australians. There was overwhelming support for the restriction of non-Europeans to Australia. Thus Greg Lockhart wrote recently of the ‘economic as well as psychopathic foundations of settler conquest’. He mentioned, too, ‘the prosperity from gold and imperial trade preferences that accompanied and followed the continental land heist’ which ‘helped to stabilise the colonial culture’s all too doubtful sense of self-importance’. [5]

Showing great faith in its audience, the Parliament House exhibition takes this historical context for granted. In the list of what it calls Barton’s legislative ‘achievements’ it includes the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 and the Pacific Islands Labourers Act 1901. As for the much-vaunted Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902, it enfranchised certain women only (‘all persons not under twenty-one years of age whether male or female married or unmarried’: s. 3). White women, that is, because, in the very next section of the Act, it states no ‘aboriginal native of Australia Asia Africa or the Islands of the Pacific except New Zealand’ was qualified to have their name on the Roll.

In April 1902, King O’Malley, a member of the House of Representatives from Tasmania, interjected during debate on the Bill that ‘An aboriginal is not as intelligent as a Maori. There is no scientific evidence that he is a human being at all.’ There were no protests from suffrage activists. Years ago, Humphrey McQueen reminded us just how racist the labour movement was, and today Clare Wright for one has highlighted the gender hypocrisies, pointing to the shadow side of celebratory nationalist narratives and suggesting that ‘Instead of fighting shoulder to shoulder, as our suffragists did, we could begin to walk side by side, as our First Nations are asking us to do’. [6]

It would be naive to imagine Parliament’s presiding officers, in marking the centenary of his death, commissioning a life-and-times view of Barton other than as the federation hero and wise helmsman of the young nation. But if they did, the person to curate it, I suggest, would be another Barton – great grand-daughter, Anne. In an issue of the Indigenous Law Bulletin in 2011 she wrote of ‘Going White: claiming a racialized identity through the White Australia Policy’,[7] and earlier this year, lent her name to protests urging the removal of an Edmund Barton statue from an Indigenous burial site in Port Macquarie (part of the NSW Assembly electorate of Hastings-Macleay, which Barton represented in 1898-1899).

Barton’s grave, South Head Cemetery, Sydney (Wikipedia/Pomahob)

Barton’s grave, South Head Cemetery, Sydney (Wikipedia/Pomahob)

The ABC reported:

Ms Barton said she had much respect for former prime minister Barton but that she was not going to pretend he was not part of a project that “killed and destroyed people’s lives”. “He’s one of the people who put everything in place to make it this idea that Australia is a sovereign nation and that there was no-one here before white settlers came – the idea of Terra Nullius,” she said. “But I think we’re now, at this point, very aware that these lands were not ours. He was a man of his time and he was deeply racist. A lot of the people in the Black Lives Matter movement are talking about how police cannot see black people as humans — that’s what my great grandfather did — he and his mob.” [8]

Around the same time, Linda Burney, the current member for the federal electoral division of Barton, said she did not want its name changed but noted that “our first Prime Minister was one of the architects of the White Australia Policy, and I just love the idea that there is now a First Nations woman representing the seat’.[9]

***

In summary then, the exhibition does very well what it sets out to do. It presents the basic details of Barton’s contribution across the standard divisions of his life. Up to a point, it is thought-provoking while leaving anyone wanting more to learn via a little web browsing through other sources (David Headon’s exhibition launch speech and Geoffrey Bolton’s 2000 biography), specialist debates (James Thomson on Barton and the Australian Constitution in Federal Law Review 15, 2002), projects (‘The First Eight project’) and protests (Barton’s statue in Port Macquarie).

* Michael Piggott AM is a semi-retired archivist with many years’ experience, and has been Chair of the (ACT) Territory Records Advisory Council. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. His latest work is a chapter in Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity (Bastian & Flinn, ed., Facet, 2020). He has written many book reviews and other pieces for Honest History (use our Search engine), most recently a review of I Wonder: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis, edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark.

[1] https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/original/00005775.pdf

[2]https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2FOSWQ6%22

[3]https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2020/January/Barton_100_years_on

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/nov/06/the-brutish-museums-by-dan-hicks-review-colonial-violence-and-cultural-restitution

[5] https://johnmenadue.com/heart-of-darkness-our-expeditionary-imperial-culture-and-alleged-war-crimes-in-afghanistan-and-elsewhere/

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/aug/26/australia-doesnt-have-much-to-show-for-celebrating-womens-achievements

[7] https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IndigLawB/2011/13.pdf

[8] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-26/relative-backs-removal-of-edmund-barton-prime-minister-statue/12387258

[9] https://www.lindaburney.com.au/media-releases/2020/6/24/scott-morrison-was-social-services-minister-when-robodebt-created

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.