Margaret Pender*

‘The lonely life of the last lighthouse keeper’, Honest History, 15 August 2020

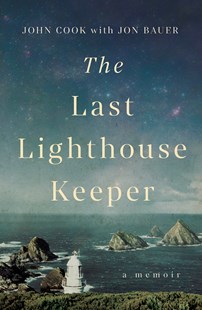

Margaret Pender reviews The Last Lighthouse Keeper: A Memoir, by John Cook with Jon Bauer

The idea of lighthouses conjures up images of man battling the elements, perilous sea rescues and stories of human endeavour. There is also the nature and vulnerability of the dedicated lighthouse keepers. In fact, the main role of lighthouses was to ensure the safety of shipping and to help ships confirm their location at sea.

John Cook’s career as a lighthouse keeper began in late 1969, when he was recruited by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service. He and his de facto wife, Deb, were escaping their respective earlier marriages and each had been denied access to their children. They were seeking a new start.

John Cook’s career as a lighthouse keeper began in late 1969, when he was recruited by the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service. He and his de facto wife, Deb, were escaping their respective earlier marriages and each had been denied access to their children. They were seeking a new start.

Like many lighthouse keepers of the time, John Cook had spent time in the Merchant Marine. This may have helped prepare him for their arrival at the Tasman Island Lighthouse, situated in Bass Strait, in the middle of the Southern Ocean outside Storm Bay and the approaches to the Derwent. The l29 metre high lighthouse was dwarfed by 250 metre cliffs that rise abruptly out of the Southern Ocean on all sides of the island.

John and Deb were transferred from the lighthouse tender, the MV Cape Pillar, to a working launch, where they then got into a basket suspended from a flying fox on the cliffs. From here the basket was winched upwards to a landing edge about 30 metres up the cliff face. An engine-driven winch took them up a steep tramline to the top of the cliff and transferred them to a whim or windlass that moved them on to the lighthouse. Just looking at the photos of this in the book is scary.

Here they met the other lighthouse keepers, Dan and David, and their families. There were three families working on most lights then. Being married was a requirement for the job, and John and Deb had lied about their marital status in order to qualify.

John adapted quickly to the lighthouse routine, rostered on for nightly three-hour shifts, tending the kerosene light, cleaning its many facets, and during the day maintaining the machinery, the flying fox, the winches, and mowing the grass. There was no refrigeration: a flock of sheep provided fresh meat for the families, with one slaughtered every fortnight. It was a physically demanding routine. Deb was often lonely and called the island Alcatraz. John missed his children dreadfully, and this is a major theme of the book. The couple had brought with them their two dogs, some chooks, as well as a baby kangaroo they had smuggled onboard the ship. This domestic menagerie played a large part in their lives.

The lighthouse tender came to the island every three months to deliver supplies – maintenance materials for the lighthouse, as well as fresh fruits and vegetables for the families, briquettes to heat the cottages, library books … It also came to collect anyone who was ill and needed medical or dental attention. Communication with the outside world was by radio telephone, an open line that connected all the lighthouses to head office.

Developments in technology, the replacement of kerosene lights by automated electric ones, and navigational developments like the Global Positioning System (GPS) spelt the end of manned lighthouses in Australia. In a sense, this book is an account of a way of life that is gone forever.

The book contains some wonderful descriptions of the natural world, not only high seas and devastating storms, but also accounts of the mutton birds on Tasman Island, the arrival of the fairy prions coming there to nest in spring, and John’s sighting of a blue whale. Sadly, these pieces are few and far between.

A central theme of the book is John’s grief about being denied access to the children of his first marriage. When he is on leave in Hobart, he breaks into their house and sees them sleeping, something that enrages his first wife. (This was in 1971, before the passage of the Family Law Act 1975.) By the time he’s on Maatsukyer Island, he’s allowed access, and his daughter Frannie visits him.

The book’s chronology is both strange and confusing. John Cook was in the lighthouse service for 26 years, from 1969 to 1996, but the book covers just the first two years of his time on Tasman Island (1969-71), and then a small part of the eight years he spent on Maatsukyer Island.

Tasman Island (Wikipedia)

Tasman Island (Wikipedia)

The book is well-written, co-authored by Jon Bauer, who Cook credits with ‘successfully turning his manuscript into a wonderful book, partly fiction but mostly true’. Its main focus, almost to the exclusion of everything else, is the story of the breakdown of John and Deb’s relationship.

And it is a memoir, something the New Yorker described recently as being born of a powerful need to craft a story out of the chaos of one’s own history. It goes on to say that one of a memoir’s great satisfactions – both for writer and reader – is the slow, deliberate making of a story, of making sense out of randomness and pain.

* Margaret Pender is a retired Commonwealth public servant. She has reviewed several books for Honest History (use our Search engine), most recently World War Noir: Sydney’s Unpatriotic War by Michael Duffy and Nick Hordern.