‘Parting not such sweet sorrow’, Honest History, 4 November 2015

Michael Piggott reviews Norman Abjorensen’s The Manner of Their Going: Prime Ministerial Exits from Lyne to Abbott

I was in a bus on a group tour in Turkey when the news came through of Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership challenge, and soon after, of the ‘coup’ itself. Among all of us, two-thirds Canberrans, animated discussion followed. There was no concern that this was our fifth prime minister in five years, just instant speculation about the spoils for winners and fate of losers, and who would be the new ministers. We blithely assumed democracy ruled (within the electorate and parliamentary parties); transitions of executive power are orderly in 21st century Australia and removing a leader is nothing unusual.

Our tour guide, a highly educated and politically aware Turk, asked what had happened. When we tried to explain, his puzzled and slightly shocked face showed how little we had succeeded. Yet, however much different cultures define value and enforce political stability, one element is common. As Norman Abjorensen observes in his new book, to tell of how power is lost or relinquished is ‘to inject a very human factor into the often brutally impersonal world of politics and power’. It is invariably ‘a study of imperfection’; it is ‘the story of Ozymandias’.

Our tour guide, a highly educated and politically aware Turk, asked what had happened. When we tried to explain, his puzzled and slightly shocked face showed how little we had succeeded. Yet, however much different cultures define value and enforce political stability, one element is common. As Norman Abjorensen observes in his new book, to tell of how power is lost or relinquished is ‘to inject a very human factor into the often brutally impersonal world of politics and power’. It is invariably ‘a study of imperfection’; it is ‘the story of Ozymandias’.

Books by and about Australia’s prime ministers began appearing in earnest from the 1960s with the appearance of JA La Nauze’s two volume Alfred Deakin: a Biography (1965) and RG Menzies’ Afternoon Light: Some Memories of Men and Events (1967). They haven’t stopped. A related trend, collective treatments like Don Whitington’s Twelfth Man? (1972) and Colin Hughes’ Mr Prime Minister: Australian Prime Ministers 1901-72 (1976) soon emerged.

Since then, something of a prime ministerial studies industry has developed. Diaries, anthologies of speeches or quotes and consolidated opinion pieces have joined the growing list of autobiographies and memoirs, while, complementing biographies and narrower scholarly studies, there have appeared prime ministerial libraries, websites, documentaries, accounts by speechwriters, staffers and other insiders, and an Australian Prime Ministers Centre within the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Loosening our categories slightly would also allow in novels and musicals.

Of the collective genre, few have managed to get beyond the biographical survey. The survey was a relatively simple task in the 1970s when, with some judicious selection, a monograph would easily handle one chapter per PM. In From Barton to Fraser: Every Australian Prime Minister (1978) and Profiles of Power: the Prime Ministers of Australia (1990) Brian Carroll and Graham Fricke found ways to deal with the growing numbers, while in the new century, successive issues of Michelle Grattan’s authoritative edited anthology Australian Prime Ministers have simply grown bigger and bigger.

Only rarely has a fresh angle been offered. Some scholars have focussed just on a few prime ministers, as Judith Brett’s authors did looking at, among other politicians, prime ministers Hawke, Keating, Whitlam, Fraser and Menzies for her edited Political Lives (1997). Five years earlier Di Langmore had thought laterally if still selectively, producing Prime Ministers’ Wives: the Public and Private Lives of Ten Australian Women (1992). Walter and Strangio were selective, too, in their little gem No, Prime Minister: Reclaiming Politics from Leaders (2007). Last year in her Dean Jaensch Lecture Michelle Grattan looked at how prime ministers from Whitlam onwards dealt with their first year in office.

James Scullin (1929), prime minister 1929-32, and hat, in his office (National Archives of Australia A3560, 3187776)

James Scullin (1929), prime minister 1929-32, and hat, in his office (National Archives of Australia A3560, 3187776)

Now, Norman Abjorensen has examined how prime ministers’ careers end. There are many reasons to praise The Manner of Their Going, starting with the concept of exit as a way to retell each prime minister’s story. It is a simple yet highly effective angle, because so much of politics is about the unfolding drama of gaining and maintaining power, especially the top job itself. The rationale is there in the opening paragraph of the Introduction: while Keating and Howard observed that a change of government can change the country, sometimes so can changing the government’s leader.

Abjorensen’s approach is broadly chronological but quite complex. His novel opening explains why Sir William Lyne – who, in a vice-regal blunder, was actually commissioned and thus became technically our first prime minister – was unable to form a government. Fifteen more chapters follow, some focussed on a single man, some bracketed by a common ending (for example, ‘died in office’) or status (stop gap ‘seat warmers’). At the end there are chapters on the mutually assured destruction of Rudd and Gillard titled ‘Labor’s MAD Wars’, and on Abbott – an impressive effort given the planned timing of the book’s publication, almost coinciding with Turnbull’s success.

These chapters are followed by an epilogue on PMs’ afterlives and a reproduced review by the author of Mungo McCallum’s The Good the Bad and the Unlikely: Australia’s Prime Ministers (2012). This otherwise indulgent inclusion is saved by a piece of pure theatre because, at the end of the review, Abjorensen suspends disbelief to conjure all 27 former PMs into a room and describes ‘who … would be speaking to whom, and what about?’ One can overlook Abbott’s absence here, while struggling to imagine him feeling comfortable with any of his predecessors (or his successor), which is perhaps another reason to agree with David Marr’s immediate post-coup assessment, ‘a unique man and a unique failure’.

To offer a sample of Abjorensen’s writing, and to allow readers to try to place Abbott, the following longish paragraph is worth reproducing:

Genial George Reid, glass in hand, would be the centre of the crowd at the loud end of the room near the keg, probably swapping stories with Barton, Artie Fadden, Hawke and Gorton, with a deaf Hughes trying to follow the talk. Chifley, drawing on his pipe, might be in reflective discussion about the Labor Party’s vicissitudes with the tea-drinking Curtin, attended by Scullin and Forde. Menzies, the Anglophile Stanley Bruce and Howard would be talking cricket; Gillard and Holt in amiable conversation; Keating telling Watson and Fisher where the early Labor Party went wrong. Deakin and Whitlam would be discussing Roman history; Earle Page would resume his argument over the future of the Country Party with McEwen. Cook, one suspects, would be looking on disapprovingly from a corner, possibly talking to a lonely Lyons with Fraser keeping to himself and Rudd still wondering what happened.

Gough Whitlam, prime minister 1972-75, visiting New Delhi with Mrs Whitlam (1973) (National Archives of Australia M151, 6821483)

Gough Whitlam, prime minister 1972-75, visiting New Delhi with Mrs Whitlam (1973) (National Archives of Australia M151, 6821483)

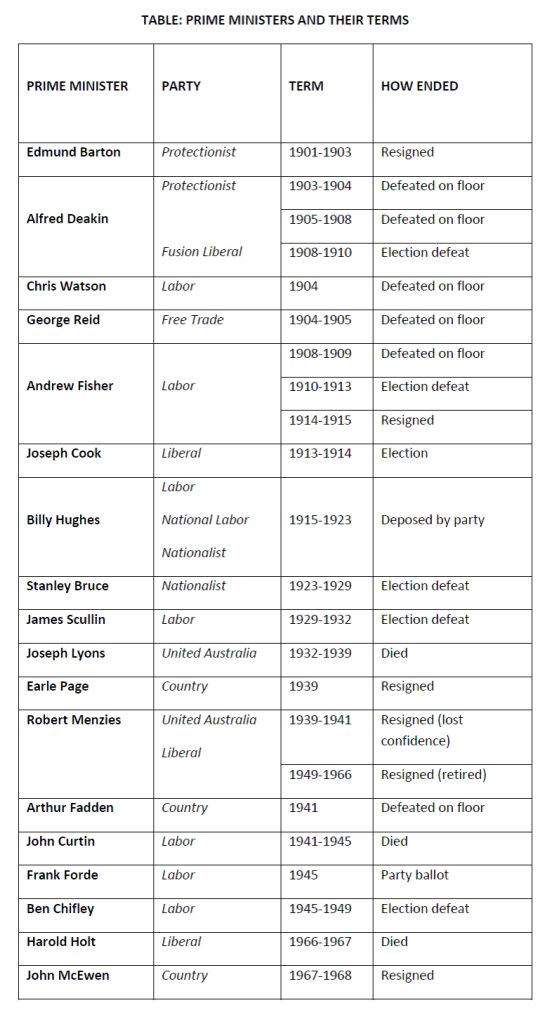

To me, the key to the book’s success is that, in explaining each PM’s rise and fall, and by incorporating the relevant personal, party political, parliamentary and electoral contexts, Abjorensen has produced in effect a collective account of every prime minister. Accordingly, the book should immediately become a resource for pattern hunters. Some themes are there in the table summarising each PM’s details and the nature of their ending (resigned, defeated on floor of House, electoral defeat, died, party ballot, and so on, not forgetting dismissed by Governor-General). (See the table at the end of this review, taken from the book and reproduced by permission.)

What struck me is how many PMs began their terms not in the best of health or quickly succumbed to the strain of holding office, how bitter and vicious ambition and revenge can become in the fight to gain and keep the top job, and how many prime ministers faced a hostile Senate.

Abjorensen’s sources include the occasional archival document or oral history interview, understandably drawing on the existing literature. His distillation of these vast secondary sources is masterly, as the 1100 endnotes attest. (My only quibble is his describing David Day as ‘Fisher’s biographer’ and failing to mention Peter Bastian’s work). As a journalist, Abjorensen met 15 prime ministers and he also uses his own personal sources. The result is a pure pleasure to read. I nearly wore out a pencil writing ‘nice!’ in the margins of my printout (the review copy being a pre-publication pdf). Deft, telling phrases flowed from Abjorensen’s fingers to capture the core of each personality, which he complemented with many others’ pen portraits and often cruel skewering labels from Hansard, diaries and the city dailies.

The best books make you think. I want to turn now to several more general points raised in my mind by The Manner of Their Going. The first is to wonder what would emerge if one extended the analysis to include state premiers. Would this add to the list of different kinds of endings? Would it reinforce the pattern Abjorensen has already discerned, with over one- third of his 28 leaving through electoral defeat, and his one big conclusion, a common reluctance (with one exception – guess who) to relinquish office? After all, many of the same contexts and forces condition both prime ministerships and premierships. The parallels are stronger than suggested by noting that two PMs were ex-premiers; there have been 30 ex-premiers (and two chief ministers) who moved to Canberra, a surprising figure even granted that 12 made the move at Federation. (See Antony Green’s blog on this subject.)

Secondly, while this book’s treatment of prime ministerial afterlives is understandably short, we might acknowledge there is much more to be said about this subject. Ceasing to hold the highest office is usually not the end of a life. What are the patterns here, the explanations? (In this regard, Troy Bramston says ‘We could do more with ex-PMs’.)

William McMahon (prime minister 1971-72) and John Gorton (prime minister 1968-71), 1969 (National Archives of Australia A1500, 7648093)

William McMahon (prime minister 1971-72) and John Gorton (prime minister 1968-71), 1969 (National Archives of Australia A1500, 7648093)

Adding memory politics and history-making opens many further questions, not least the management of legacy, the odd number and nature of prime ministerial libraries, and perpetuation of the name and the attitudes surrounding gravesites and homes. Graves certainly interested our most recent former prime minister. In October 2013 he floated the idea of a national war cemetery in Canberra – as an Anzac centenary idea, of course – possibly for Victoria Cross winners, ex-Governors General and former PMs. (The idea seems to have been scotched with the proponent’s departure.)

Which leads to my third point. One of the three prime ministers to die in office, John Curtin, essentially worked himself to death leading the country during World War II. Hal Colebatch for one seems comfortable to blame strikes and psychological tormentors as well as underlying health as lethal factors, while still concluding Curtin ‘gave his life for his country as much as any soldier in battle’. Reading Abjorensen’s measured and heart-rending account (which interestingly ignores Colebatch’s more recent writing) it is hard to disagree with Colebatch.

The Australian War Memorial would quickly cite its legislation and never add Curtin’s name to its Roll of Honour, but the military protocols which dominated his funeral are suggestive, as is the presence in the Memorial’s collection of the RAAF Dakota A65-71 which flew the body to Perth. Surely Curtin was, as Abjorensen, like Colebatch, wrote, ‘as much as any fallen soldier, a casualty of war’.

To end – because readers must surely know what I think of Abjorensen’s book – with something frivolous. For trivia buffs as much as those seriously interested in the details of Australian political history, The Manner of Their Going is truly a gift, a mine of unusual and unexpected facts. It will provide answers to any number of questions, such as:

- Who was Australia’s eighth prime minister? Hint: he was the first occupant of the position not to have previously served in a pre-Federation colonial Parliament.

- Is it true Gorton brought himself down with a casting vote in a meeting of his parliamentary colleagues?

- Name the two PMs who never sat in the House of Representatives as PM?

- Who was ‘Stabber Jack’?

- Who represented three different electorates while Prime Minister?

- Who was the first PM (with all his ministers) not to have previously held ministerial office?

- Who was the first PM to win office from opposition?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.