‘On Sydney Harbour with the prime minister of South Vietnam, 1967: Daniela Torsh interviews Max Humphreys’[1], Honest History, 19 September 2017

Kirribilli House from the Harbour (Wikipedia/Stephen Bain)

Kirribilli House from the Harbour (Wikipedia/Stephen Bain)

Daniela Torsh: So Max, I’ve got a question to start with: tell me what the mistakes are that you think are in the article?[2]

Max Humphreys: OK, well the article is full of mistakes, apart from its general gist which is pretty much in line with what happened. The details though of the demonstration that the article is mainly concerned with, which was the one that was held down initially outside the rear of Kirribilli House[3], and then under the Harbour Bridge … seems to be remembered fairly inaccurately in nearly all details by Bob[4] including details of myself and who it was that he rushed around with [to North Sydney police station].

As I remember it, the overall details of that demonstration[5] were that we marched to the rear of Kirribilli House. However when we got there the people running the march decided that it was all going to be a bit too much, and they turned the march around encouraged by the police and went back under the Harbour Bridge, where it was also obvious that we weren’t going to be able to see Marshal Ky[6] coming in on his boat or leaving Kirribilli House.

Tom Uren MP (Daily Telegraph)

Tom Uren MP (Daily Telegraph)

Once we got back under the Harbour Bridge various people made speeches: Tom Uren[7] and a very boring speech by Arthur Calwell[8]. In any event, I got very frustrated; I’d been a founding member of the Sydney University Vietnam Action Committee, from very early stages, if not from its inception, with a number of other people, one of whom was Lynne Hyman[9], who I think maybe Bob may have mistaken for you. Lynne was a girlfriend of mine at the time and we together with various other people, the Aaron [sic] brothers, at least one of whom is now in the Labor Party, working as a Labor Adviser

D: You mean Mark [Aarons]?[10]

M: Might be Mark, one of the Aaron brothers.

D: Aarons.

M: Aarons … Aarons brothers, anyway and there was another chap, who was a sort of a pimply young guy, who was one of the first Liberal Reform characters who was a bit of a religious Christian pacifist who took exception to the war, and a few others. But there was only really a handful of us. As I remember Bob was in charge of the Central Committee or something of the Vietnam Action Committee, or the Sydney sort of branch or whatever. Anyway I wasn’t terribly involved with any of that but I felt it was important for me to let him know what I was intending to do, when I decided to get on my surfboard … so I certainly didn’t gazump anyone. Bob was entirely aware of what I was going to do and was not at all interested or supportive.[11] I remember having two conversations with Bob Gould at demonstrations. The first one being in Canberra when I got up on the roof of the hotel there and pulled down the South Vietnamese Flag and did a ‘Heil Hitler’ to Marshal Ky.

Part of my attitude at the time was I had researched to some extent what was going on in Vietnam in the early days and that’s why I became a member of the Vietnam Action Committee at Sydney Uni and decided that not only was I against the war but I was outraged by it and our involvement in it seemed to me to be unbelievably stupid. Part of what I’d read about in that period was about our friend Marshal Ky who at that stage wasn’t in charge of the puppet government that America had put in power but he was just a General [sic] at the time but an up and coming one and he was a great admirer of Adolf Hitler. This was one of his claims to fame, amongst his friends. He’d graduated as a pilot in the French Air Force academy. To find out that he was being invited out here and really given the red carpet treatment, really gave me the shits! So this was the reason that I demonstrated in a fairly individual way, both times when I had a chance.

Anyway the demonstration was pretty much thwarted I thought in its effect by being brought back under the bridge and out of sight of Ky and his party so as an attempt to do something about that, I got on my surfboard which I happened to have on the car because I’d just been surfing on the South Coast [of NSW]. Actually I’d come up from Melbourne[12] from a student conference that I’d been to and still had the board on top of the car so I jumped on the board and grabbed a couple of posters from people that I tested and found to be waterproof. The fact that they were water proof was their main claim to fame; as far as I was concerned they could have been any posters. But one of them said ‘Butcher Ky’ and the other one said something similar. There was no need for posters anymore because no one except the converted could see them.

D: Hang on, so I’m asking you about the mistakes, in this article?

M: OK, so I’m dealing now with the overall mistakes of what events occurred. So the events as I recall them were that the demonstration attempted to turn out at the back of Kirribilli House, and make quite a noise that would have been heard by the dignitaries that had gathered to meet with Marshal Ky when he was brought back from his harbour trip.[13]

He was being shown the harbour on a special cruise[14] and now he was coming back to Kirribilli House in the afternoon. The problem with that idea was as I said that it was quite congested behind Kirribilli House. There was a lot of concern amongst various people as I remember it that people might even end up getting hurt. In any event the people controlling the demonstration decided that we would go along with the police suggestion of leaving and going back under the Harbour Bridge. That’s the first thing and then the speeches and things that occurred under the Harbour Bridge, apart from being bored by what poor old Arthur [Calwell] had to say. I don’t remember anything else about them but I felt we were a long way away from Kirribilli House at that stage and not effectively demonstrating against this total dickhead fascist Marshal Ky who was being run around the harbour. So I felt, if I got on my board quickly enough, and paddled round there with some appropriate placards tied off around me, I’d be able to make a presence, so that’s what I did.

D: So where did you go into the water?

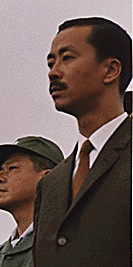

Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky (Wikipedia)

Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky (Wikipedia)

M: I went into the water right near the Harbour Bridge and paddled around from there to Kirribilli House. It’s not a long paddle but it would have been probably about half a km or something around there. On the way around, I remember noticing a few little vessels and things I don’t know what they were about – basically there was no-one there – but when I came around the corner, I could see this vast number of police who now had nothing to do because the demonstration under the bridge was causing them no concern.[15] And they all gathered on the wharf that is at the bottom of Kirribilli House, and I imagine that there were a lot of sort of important looking people there, but being a little bit short sighted I couldn’t really see what was going on there. But I could see a whole lot of people and I knew that‘s where the boat was going to come in. Somehow I figured that out.

Anyway I just paddled straight for there and I got there before Ky’s boat. Another error is that … the Water Police never arrested me. They did try to but it was the Rescue Squad so called, some guys in white overalls that actually attempted to ‘rescue’ me at one stage. The Water Police came in and out about 5 or 6 times, I’m not too sure how many … maybe even more than that and pleaded with me to get on board, but I wasn’t there to do that. I was there to make sure that I got the message to Marshal Ky that not everyone in Australia was happy with him. So I kept on evading them by flipping the surfboard around and paddling in close to the wharf, which meant that I was very close to all these other police and officials on the wharf. Maybe some of the police came around ‘cause they saw me coming. I had no idea why there were so many police there but there were a lot of them there. Each time I’d go in there they’d sort of reach out from the wharf and try and grab me but I was too far away from them to grab.

It was sort of half tide I think fairly low tide and then I’d swing around and paddle back out because the launch had to turn around because there was a rock just on the western end of the wharf, so I’d paddle in towards that rock, swing around and paddle back out again. The Water Police would go out and come back in again. Then eventually these guys, who I thought were just some right wing fascist maniacs with an outboard motor and a small dinghy came flying towards me and tried to grab my board, and I really thought they were out to kill me!

I grabbed the front of their boat and started to rock it, because they were trying to grab me. One of them did fall over I think and then he got up with his oar and belted me over the head at some stage, in that little battle, they got my board off me, into their boat and took the board. They then continued to come at me with their outboard motor, their little dinghy type thing. It wasn’t a rubber ducky, it was aluminium …

D: Like a tinnie?[16]

M: Yes like a tinnie. It was a tinnie probably. Same sort of thing. And they would come roaring towards me I’d grab the front of the boat and they’d stand up to try and grab me and I’d rock the boat and they’d sit back down again. That happened a number of times.

D: And were you standing up by this stage?

M: No, I was still in deep water but I was pretty fit.

D: You’re not on the board? They’d taken the board?

M: No, they’d taken the board, they’d hit me over the head and I was bleeding all over the place and they were trying to grab me and drag me on board. Up till now even at this stage I thought they were just right wing ratbags. I had no idea that they had anything to do with the police. They had these overalls on.

D: They didn’t identify themselves?

M: No, no, not at all. The Water Police did and they were obviously identifiable anyway, but these guys didn’t identify themselves they just came straight at me with a boat.

D: Did you realise that there was a TV camera?

M: No, I found out later that there was this part of it, when I got hit over the head with the oar, and this sort of thing, it was on the night news.[17] But all that footage disappeared shortly afterwards. And there were also some still shots, which the lawyer representing me later, just trying to think of his name …

D: Jim Staples?[18]

M: Jim Staples yeah, managed to get hold of these things from the [Sydney Morning] Herald. And because they were just still photos, the judge had a lot of trouble working out the positions of where things were and where the water police were and that sort of thing. At no stage did anyone accept the fact that I didn’t know who these guys were, including probably Jim Staples. Although he did take note of most of what I said and consequently got at least one of the guys thrown off the police force. But anyway, that’s another story.

On the day the events were that they did this and then they actually appeared to give up, they said something along the lines and that’s when I realised, when they looked up and spoke to the people on the wharf, that they were connected with the people on the wharf. They said, ‘Look this is just hopeless; we’re going to end up being tipped in the drink. So we’re going.’

So they turned around and left. So at that stage a boat appeared to come around the corner, which I assumed was the boat that had Marshal Ky on it, and the Water Police came in again but this time they were so high up in the air and I was down in the water, that they couldn’t have reached me, anyway I don’t think, anyway they didn’t get me and I don’t know why they didn’t come in and drag me in then but they didn’t.

What happened was that some crazy cop dived off the wharf and he proceeded to swim towards me, and I could tell he wasn’t a great swimmer[19] and by the time that he got up to me fully clothed, he wasn’t any match for me, in terms of staying afloat, and dragging me in.

He didn’t say anything to me, about arresting me, or anything along the lines of what you were saying before: he was just trying to grab me. And he didn’t have a chance. So in the end I could see that he was going to drown, so I actually grabbed him and tried to get him to where he could stand, but when I got him closer to the shore, some other guy grabbed me. He was the guy who eventually egged the other guy on to bash me up. This red haired guy grabbed me, and these names are all on the record, ’cause these were the guys that arrested me, so they’re not mysterious people, they’re well known, I mean they could be identified.

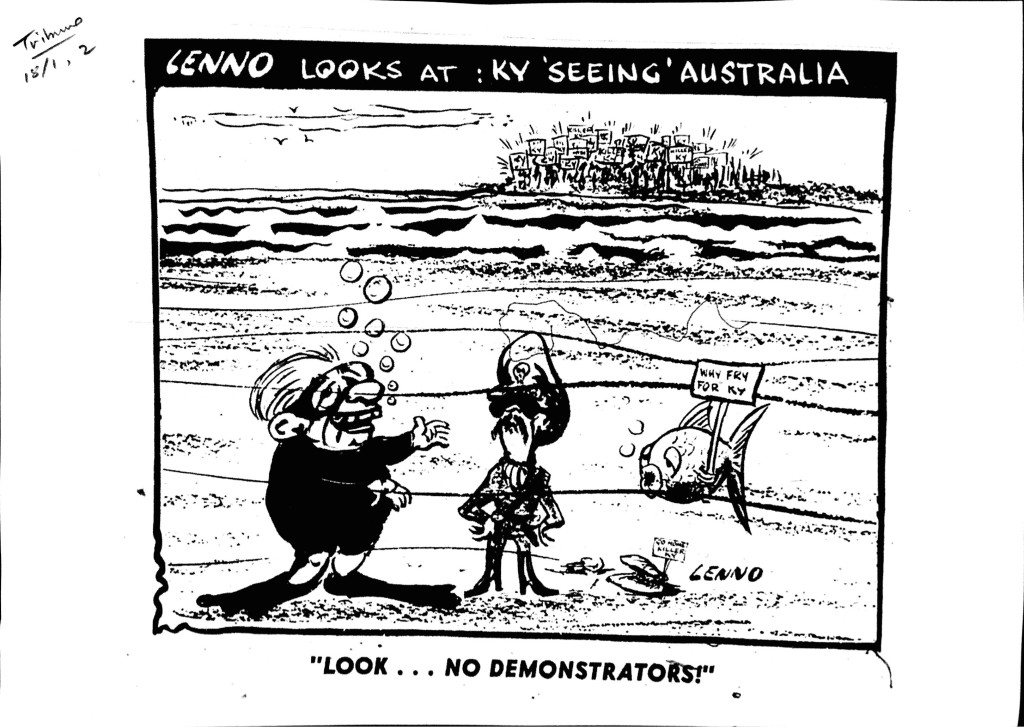

Lenno cartoon with Ky and PM Holt, Tribune, c. January 1967 (Labour History, Melbourne)

Lenno cartoon with Ky and PM Holt, Tribune, c. January 1967 (Labour History, Melbourne)

In any event they then proceeded, those two guys and a couple of other guys got involved, proceeded to push my head into the barnacles and oysters and things, on the sand which is where I got most of the cuts under my chin. Then they dragged me through the barbed wire, which they had to do to get me in to the Kirribilli House cause I wasn’t in Kirribilli House at that stage, I was on the outside of it. And they dragged me ashore. So they dragged me though this fence, I got a few cuts from that, but pretty superficial but the real damage they did was later on when they got me up into the garage which is where the demonstration originally started, so it was up the back of Kirribilli House and there were police cars there. There was one sort of wagon, that they put me in, eventually which as I remember it to this day was a long narrow sort of metal tunnel.

I did hear later, that someone had threatened the life of Marshal Ky or something.[20] How they thought that someone in a pair of swimming costumes and nothing else was going to kill someone, I don’t know, but that’s what they were claiming. And they, by they I mean now, there’s about, I don’t know at least 20 cops around there, they were chanting at this guy and egging him on to bash me up. But this is the guy that I’d actually saved; he didn’t really want to bash me up. Psychologically, it was difficult for him to do it, despite the fact that his mates were egging him on. So it was just a real bully sort of thing. And anyway eventually he did get stuck into me. And that’s all I remember, apart from waking up in this long tunnel thing.

And I told all this to the barrister later, and I included in it my memories of what happened when I got to the police station, which incidentally, just for the accuracy of the record, was North Sydney Police Station. And they left me in my swimming costumes, in some sort of like booth or something, that was at the front of the police station, initially and just left me there. Which was a big mistake for one guy, because he then proceeded to try to make a false claim … and I was pretty groggy after being bashed, but I remembered him making this claim for his diamond ring and a watch. Which later came up in court and which was why I gather he ended up getting kicked out of the police force.

Jim Staples was able to prove that, so I think that was really the only success at the court case. I got arrested for all the things that they wanted to charge me with, including resisting arrest and malicious damage although maybe not the malicious damage, because that turned out to be his watch and the ring. That didn’t sort of go down too well when they found out that he’d actually bought them after the event. So anyway, they were facts of the day. And as far as people getting me out on bail that I’m not sure of … I’d have to look to you …

D: Hang on stop, stop did they at any point offer you any medical assistance?

M: No, no. They took me from the front, when they realised I was conscious and could hear what they were saying, they took me from the front and put me in a cell. At which stage the strong memory I had was I had this fairly juvenile, but I think probably fairly accurate idea based on my knowledge of Australian police, that maybe a lot of them were Irish.[21] So I began singing Irish protest songs, ‘Gavin Barry, only a lad of sixteen summers, ‘cause no one can deny that he went to death undaunted’, and that sort of thing, very loud, and probably very out of tune, but echoing all through the police station! So they no doubt enjoyed that – hopefully not! – and eventually someone did come and I did get out and I did end up at Chatswood[22], I remember that.

D: But you don’t remember who got you?

M: I don’t remember who it was who got me out …

D: It was Reg and I.

M: Yes, that seems right.

D: It was quite late in the day, at …

M: I didn’t remember it being Bob Gould.

D: So did they at any point offer you the phone to let you ring anybody?

M: No, no.

Arthur Calwell speaking at the Harbour Bridge demonstration (Labour History, Canberra)

Arthur Calwell speaking at the Harbour Bridge demonstration (Labour History, Canberra)

D: ‘Cause I don’t know how we found out that you were there?

M: Well.

D: There was a phone call to Reg [Humphreys],[23] I remember.

M: Probably Lynne would’ve rung and told you.

D: OK. Somebody rang and spoke to Reg.

M: I think Lynne came around with Bob Gould; that’s what I think happened. In retrospect, it’s what people told me afterwards, that they came round. They found out. She rang Reg ‘cause I gave her the number. They never gave me a phone to ring or anything.

D: So you were conscious enough to know your phone number.

M: I think if they’d given me a phone, at the point, when they put me in the cell, I would’ve been able to ring, but I think if they’d given me a phone, initially, I wouldn’t have [called someone].

D: How did you know that Lynne and Bob went around to the police station?

M: Afterwards. I don’t remember that happening.

D: How did you know that?

M: Well afterwards I think Lynne said that she went with Bob Gould to the police station.

D: My memory is that somebody rang Reg, I can’t remember who, and I think it was the police. And said we’ve got your son here …

M: Yes, I might have given the police the phone number …

D: And we went round. It was late in the afternoon, about 4 o’clock or something and you were basically out of it, your whole body was bruised. And they didn’t even give you a blanket. And I remember we got you home, and I think Reg rang Dr Stephens[24] and he examined you and said basically you had to stay in bed for a day.

M: Well I had concussion. I mean I was crook for about a week afterwards.

D: I don’t think you had an x-ray or anything which you know really you should have had.

M: Mmm. No.

D: I mean there was never any sign that Bob or Lynne or anybody was at the police station. It was just Reg and I.

M: No I think they had gone. I think they came … Did you guys pay the bail?

D: No.

M: So he might have paid the bail, but I wasn’t released, obviously. I mean I wouldn’t have been able …

D: I don’t remember Reg having any money. I certainly don’t remember any conversation about money. I was just terribly upset at the condition that you were in.

M: No I didn’t know there was any bail. Um, well they, I don’t think at the time, I don’t have any memory I certainly wasn’t conscious of them reading out any charges. The only thing I remember was the conversation of this young constable with the Desk Sergeant which I relayed to Jim Staples. And because the Desk Sergeant had an argument with this guy about how he shouldn’t be putting this claim in. This is what got Jim Staples clued up – that this was probably a false claim. But anyway, what else is there in here that should be corrected?

D: Well what I wanted to ask you was why did Bob think you were the Education Officer of the Sydney University SRC?

M: I don’t know.

D: Was there someone there from the SRC?

M: No, not that I know of.

D: At the demonstration?

NSW Premier Sir Robert Askin (NSW Parliament)

NSW Premier Sir Robert Askin (NSW Parliament)

M: Well he would’ve known at the time that I was a member of, if that’s the right way of putting it, of the Vietnam Action Committee at Sydney University. But I was never on the SRC as you know. Maybe you were the Education Officer, were you at some stage?

D: I was on the SRC, but I wasn’t the Education Officer. But I wondered if that was where he got the SRC involved[25] because of me?

M: Well, the thing about being dreamy and blonde … I was pretty dreamy after I was bashed up but I wasn’t normally very dreamy and at the time I was bloody mad that there was not going to be a proper demo and the blonde bit of course wasn’t right. Since I had brown hair.

D: OK according to Bob.

M: I was generally very angry over the war, and more particularly annoyed that Ky was getting the red carpet treatment.

D: According to Bob, ‘he and Dany’ took all of the afternoon and most of the evening to get you out OK? And he also said that we got him out on bail at 10pm. But my memory is that we were at the police station at about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, so the timing isn’t right at all![26]

M: As far as the details at the time, I‘ve got absolutely no idea! I remember that this occurred during the day, like it would have been in the middle of the day, the whole thing; they would’ve brought me back there in the middle of the day. I don’t remember being in there that long. I was unconscious, when they brought me in; maybe that’s why they put me where they put me. I’ve been into the North Sydney Police Station since and I can’t figure out where the hell they put me. Maybe some doctor came and observed me, but it was never bought up in court, and I never remember seeing any doctor or anything at the time. They probably didn’t want to have a doctor look at me, I would suspect given that they knew what had happened.

D: Can I ask you?

M: Mm.

N: While you were paddling around to the Kirribilli House, where was the demonstration at that point?

M: As I remember it, quite clearly under the Harbour Bridge, a big group of people under the Harbour Bridge.

D: Right. So at no point did the demonstrators see you?

M: No, they couldn’t see me from where they were.

D: So how did they know that you’d been put in prison?

M: I think that the fact that I didn’t come back around, the person who would’ve been aware of that would’ve been Lynne.

D: Right. So, did you meet Lynne at the demo?

M: Yes. I don’t think that she came with me.

D: So you met up there?

M: Yes.

D: Right.

M: Um.

D: She would have realised that you didn’t come back?

M: Yeah and then panicked. She would have been panicked by my not coming back.

D: Right, which is why Bob thought it was me, or mixed her up with me.

M: Yes, what Bob doesn’t mention is the thing that happened in Canberra.[27] ‘Cause I’d recently been arrested in Canberra and released on good behaviour, for what happened in Canberra. And that did involve him, so he should remember that. And probably does because he tried to talk me out of that idea too ’cause I thought that was a good idea, and I still think it was a good idea. But he had some knowledge at the time to do with … and maybe he’s … I mean I remember him being concerned that they’d shoot. That’s all I can remember. I was by myself on that occasion.

D: In Canberra?

M: Yeah, I remember saying to him: Look no one’s going to shoot me, I mean this is Australia, I just couldn’t believe that you know … it just seemed out of the realms of possibility to me. That because I’d been up on the roof of the hotel and pulled the flag down, which is what I did and probably the most effective thing that could’ve been done at the time. But that was also out of frustration because we were all just sitting behind the thing … And the demonstration was just starting to drive me round the bend at how ineffectual it seemed to be.

D: Can I just also ask you … Bob mentions the ‘Humphreys affair’ and he says that you led a demonstration with Hall Greenland?[28]

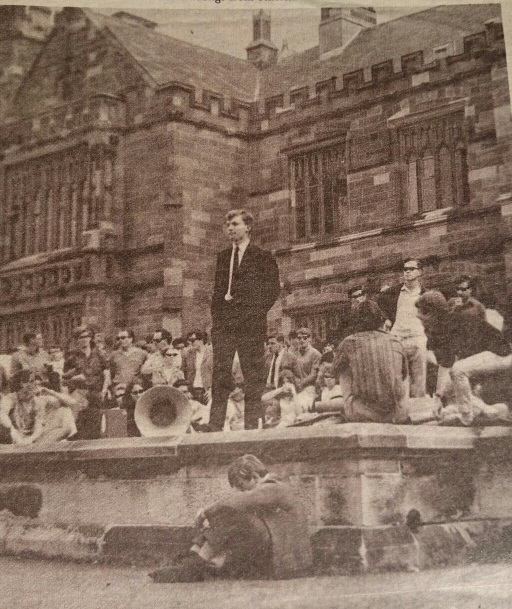

Max Humphreys (left), Geoffrey Robertson (centre), and Weir Wilson (student adviser) at the Proctorial Board hearing (see below), April 1967 (Honi Soit, 19 April 1967)

Max Humphreys (left), Geoffrey Robertson (centre), and Weir Wilson (student adviser) at the Proctorial Board hearing (see below), April 1967 (Honi Soit, 19 April 1967)

M: No, Hall had nothing to do with it. Hall got in on the bandwagon afterwards as you well know. Yeah, he got in on the bandwagon well after … the library demonstration, the library sit-in[29] which didn’t involve as many people as he says there, it wasn’t that well attended, unfortunately. It might have been two dozen people, but the library sit-in was held and called by the SARS Group, which was Students for the Action for the Rights of Students, which I did initiate I didn’t have any post[30] because nobody had posts in Students for the Action for the Rights of Students … It was a democratic group of people, who if we had a meeting [and I think we really only ever had one or two].

The SDS, which is where Hall Greenland came into it, Students for a Democratic Society, which had its origins in the USA, I didn’t know anything about it and really didn’t want to. But Hall Greenland had something to do with SDS and they came along and tried to take over our organisation. But they didn’t have anything to do with the library sit-in. Other than the fact that they may have been supportive of it after the event. Hall Greenland got up on the lawn[31] and spoke on numerous occasions afterwards in support of what we’d done.

I got arrested the morning after the library sit-in. I and a couple of others had been up all night roneoing off pamphlets about what had happened. I was handing out these pamphlets when I got arrested for inciting students to riot. That was specifically what I got arrested for. Which was some archaic law that was in the university by-laws. It was a bit unclear whether it was the talk that I gave after the library demonstration which was basically just saying that I thought it was outrageous, they brought police from outside into the university campus, just to deal with an internal matter.

I thought students should continue to resist this interference in their affairs. I thought they should stand up for having a say in what went on at the university basically, but I don’t think at any stage was there any evidence given or nor do I think I actually suggested that anyone riot or anything. I think that we were calling for … I think the pamphlets that I did have a hand in writing and which we handed out the next morning called for students to demand their right to a greater say in University affairs … It would be interesting if anyone had that on record, but I don’t think we ever called for students to riot. But maybe we did, I don’t know. But anyway we handed these things out the following morning, me and the one other person in SARS, that was the only other sort of full-on member of SARS. He was a young first year student, I’ve forgotten his name now. But he helped me hand them out the following morning and that’s when I got arrested. So I’m sure it was the morning after the library sit-in.[32]

D: Right. Just going back to the court case about the demonstration in KH, Jim Staples was your barrister, I remember the SRC[33] had like a box, collecting money for the case on the front desk, and there was a solicitor called something like Max Morris?[34]

M: Mm.

D: You don’t remember that? Because the solicitor had to instruct the barrister. But who was the solicitor?

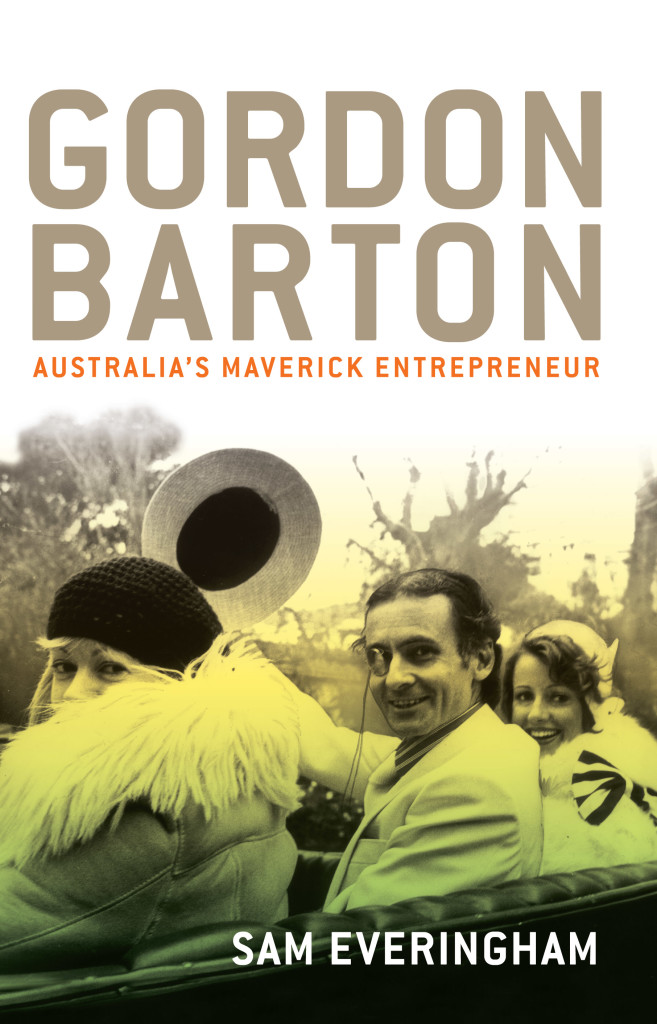

M: I don’t know. Could well be. But most of the legal expenses were paid for by, what’s his name …?; I just read the book about him.

D: Gordon Barton.[35]

M: Gordon Barton. And some other people.

D: That’s right. They called him ‘Barnacle’. If I remember correctly.

M: Mm. That’s right, exactly. We’d been to Gordon Barton’s …

D: Do you know where the court case was?

M: North Sydney court. Well it went on and on, I think I was there about five or six times. [There is a 2017 picture of North Sydney Court House – a most distinguished building dating from 1886 – right at the foot of this article. HH]

D: ‘Cause I didn’t go at all. I don’t know why.[36]

M: It kept on coming up, n’ then they’d adjourn it then they’d hold another thing … I don’t remember anyone coming with me but I do remember being lonely and pretty unimpressed by the legal system.

D: And it was just in front of a Judge?

M: Yeah.

D: Was it a criminal case?

M: Well they were criminal charges because of resisting arrest and malicious damage and stuff.

D: Right. I wonder who the judge was.

M: Also indecent language, which was one of the things I was successfully convicted of.

D: Convicted?

M: Yes. I was convicted of all charges, as far as I remember, I think even the malicious damage, I was found guilty of. I don’t remember getting off on anything. The only … success in the court case that I remember and the thing that I think Jim was pretty pleased with was that he was able to get this guy kicked out of the police force.

D: Was there any Special Branch involvement? That you remember?

M: Not that I know of. No.

D: You weren’t aware of Special Branch or the Federal Police or ASIO or anybody like that?

M: No, but they would’ve been possibly more involved with the Canberra thing. They … But that was much more straightforward. I didn’t get particularly knocked about at all in that. It was quite smooth sailing.[37]

D: OK, was there anything else that you want to add that we haven’t talked about that you can remember about the demonstration in particular that day.

M: On the Kirribilli one you mean?

Gordon Barton (monocled); the book was published in 2009

Gordon Barton (monocled); the book was published in 2009

D: That you think Bob got wrong. Yes. Because, remember the whole point of this conversation was to correct his record?

M: Yes, what he was saying about what went on in terms of people talking and so on and how many people were there, and so on. It could all be very true, I’ve got no idea, but what I was saying, the main gist of what happened on that day wasn’t that the demonstration, it makes it sound, it certainly takes away from why I got on the surfboard and paddled around to Kirribilli House, and makes it sound like that was just like a stunt that I’d dreamed up. That it didn’t originate out of frustration with the actual demonstration … and this is the reason I did it … because I felt the demonstration had turned into a talk fest with the converted preaching to the converted.

Well I was angry about the war, I was particularly incensed that we were giving this guy Ky, who I considered to be a fascist, such a warm welcome and I wanted to do something about making his welcome less warm. I had a strong feeling at the time that he was basically a, you know, I don’t know how to put the word but how to describe my feelings towards him apart from disliking him, but I thought that he was probably involved in a lot of criminal activity, from what I‘d read at the time and I still do think he was.[38] And I have read up about his life after Vietnam, because I thought I might be able to find out more about him but like Bob says in this article, he got away to America, and in America tried to encourage the Americans to trade with the new Vietnam, and got up a lot of people’s noses for doing that.

I read something written by his daughter on the Internet along those lines, that made him sound like a bit of a hero, but to me he still remains an incredibly nasty character. I‘m quite sure he was involved in lots of nasty activities that no one’s uncovered yet and I’d love to have the energy to find that all out but regardless of all that, that’s how I felt about him at the time. And that’s why I paddled around on the surfboard, I didn’t come there with that intention. It was a last minute idea based on the fact that this guy was going to come in off the harbour, not see the demonstration at all, and as it turns out, I think I was right.

Because he was coming from the Manly direction, he didn’t come from the Harbour Bridge direction, so he wouldn’t’ve even seen the demonstration. The only bright spot I’d say in the court case, since you ask about that, that I can remember I got the impression in the court case, from something the police said was that he actually might have seen me! And I think that they may have actually tried to make a point of that on the basis that that justified them doing what they did. That he was very close to there, but they had no photos to prove that. In all the photos I saw of the day there was a launch way in the background somewhere that might have been just poking its nose around the corner and turning around …

D: So when he came into Kirribilli House, he came in on a small boat, where had that boat come from?

M: It had been just taking him around the harbour for sightseeing. Just showing him a good time sort of thing.

D: I see, so he hadn’t come from a bigger ship?

M: No, he was just being shown the sights of Sydney, that’s as I remember it. He was on this boat being shown the sights of Sydney and he was going to come back to Kirribilli House, which was why the demonstration … that was announced in the paper that he was being greeted there after being shown round the harbour. All the dignitaries were going to be there and so on and so forth.

D: OK.

M: I do remember there being some pretty loud-mouthed official sort of people on the wharf shouting directions, at various people in terms of trying to get me out of the water. Not directed specifically at me as I remember it. And I don’t remember anyone asking me anything particularly sensible at the time.

D: And so do you think they really thought you were a terrorist, about to kill him?

M: Kill Marshal Ky, no. No. I mean, I think, particularly after they got the surfboard which would have been the only thing that could have been used as a weapon I had nothing on but my budgie smugglers.

D: Did you ever get that back?

M: Yes, I think I got it back. I don’t have it anymore, unfortunately but I think that’s because my cousin Leon borrowed it and didn’t return it. It’s an interesting point, because it really bugs me that I haven’t got the board anymore. I’d like to have it. I think I had to go back and pick it up from the station or something … or maybe when the court case was over I got it … I really don’t remember the details of that. I remember in those days people didn’t surf in wetsuits, so all I had on was my costumes.[39] And as you say, when you picked me up, I didn’t have anything else and I’m sure they gave me no clothing. But it was a warm summer’s day.

D: I think the cell was pretty cold. I remember the station …

M: Yes, I think that’s maybe why I was singing, yeah. It might have been air conditioned I don’t know …

D: No I don’t think it was air conditioned. It was cold, it was chilly and you were sort of blue and [your teeth were] chattering.

M: Yeah. That rings a bell. Because when you got there I was out the back wasn’t I, in a cell?

D: Yeah, I’ve got this vague memory of you coming out, we were sort of in the foyer or the lobby, and you were coming out of what looked like a cell. It was very cold and you only had your swimmers on, you were cut, all around here.

M: Yeah, that was from the barbed wire.

D: And you weren’t bleeding from your chin, but you had quite a big cut.

M: Mm.

D: And I think you had to have stitches. And I remember that your arms were just hanging down. And they were very bruised. That was very apparent.

Prime Minister Holt with President Lyndon Johnson, October 1966 (Wikipedia)

Prime Minister Holt with President Lyndon Johnson, October 1966 (Wikipedia)

M: When they hit me with the oar, they didn’t get my head each time, they hit my arms quite a bit.

D: See I am a bit shocked about you saying they hit you in the head, because I didn’t remember that …

M: Oh yeah, they knocked me out pretty much in the water initially. That’s how I think they got the surfboard. Because I don’t ever remember coming off the surfboard, but I do remember them hitting me on the head with the oar. That was in one of the photos. That was the thing that Jim Staples tried to argue, but because he didn’t succeed in convincing the judge that I didn’t realise that these people were police, which was actually the truth, I don’t think he really got to first base.

I would have probably behaved in exactly the same way, had I known they were the police, but I didn’t know they were police. And who knows how I would have reacted but I certainly didn’t think they were police, mainly from the way they were dressed, they were dressed in overalls. I just thought they were right-wing ratbags basically. And when they started hitting me over the head with the oar and stuff I thought they must be.

And so I think at one stage I actually looked up on the wharf and asked them, ‘What the hell’s going on, who are these characters?’ Because I just, because up to then it had just been the Water Police coming in and the Water Police guy was quite polite and pleasant. I mean, probably came as close as anyone could at the time to getting me to realise that I should get out of the situation. I think he could see what was coming, and he would have known about the Rescue Squad guys being sent over, in their tinnie as you say … a boat of some sort, a small boat.

I really am not sure why they couldn’t get me! I suppose because every time they came at me, I grabbed the front of the boat, that’s all I can remember doing. I grabbed the front of the boat and I pulled myself up at the boat and just start rocking it, but it wasn’t a big enough boat to not do that, and that made it impossible for them to get up and walk forward. They just chickened out.

Ky on the cover of Time magazine, February 1966

Ky on the cover of Time magazine, February 1966

There were these guys who were supposed to be Rescue guys and I imagine they would have had ropes and they would have lassoed me or something I don’t know but they gave up and they went. As I say the guy, this sort of crazy cop from Newcastle, dived off the wharf, or somewhere and he was splashing in the water and I remember thinking, ‘Oh God, here we go’. But you know as I said he was fully clothed, and just had no chance of surviving in the water very long. But I don’t know, even to this day, whether he was a good swimmer or a bad swimmer, but he certainly wasn’t much of a swimmer on that day in that situation.

D: And on the wharf there weren’t police?

M: Yeah! There was plenty of police on the wharf. I think the Commissioner of Police was on the wharf. I think that was actually raised in the court case. That I was doing all this in front of the Commissioner of Police, you know what a terrible thing.

D: And were the rest of them politicians?

M: I think so, yeah, yeah, yeah, but mainly what I saw on the wharf were police.

D: And the Prime Minister[40] wasn’t there?

M: Well who knows? Presumably someone was there to greet him but I don’t remember ever seeing anyone and as you know at the time I was fairly short sighted so I couldn’t really make out who they were and I do remember seeing a lot of uniforms, and a lot of people giving orders to other people. None of which made any sense to me, I don’t know what the hell they were on about … and mostly not directed to me, as far as I was aware. ‘Do this, don’t do that, go here, do that’, that sort of thing, that goes on when people like that get into a situation when they don’t know what to do. That I could understand, that they didn’t know what to do and that was the most pleasing part about it to begin with and the fact that I was hoping that Ky’s launch would come around, and come in so that’s what I was hoping for.

I guess that’s another thing I didn’t make clear, the reason why I stuck it out. I was hoping to get my message through to this guy at which stage I wanted to make it clear that I was the guy who pulled down his flag and gave him a ‘Heil Hitler’ in Canberra as well.[41] But I didn’t get round to that.

That was about it. The mind boggles as to how the police got out of doing all that, particularly as you say because it was caught on the news that night. They were quite obviously using unnecessary force. I didn’t resist at all when I came to shore in fact I was trying to help this guy out of the water. I wasn’t trying to resist arrest.

D: Why didn’t you appeal?

M: I don’t know. Jim just convinced me that I shouldn’t. I would have just gone with whatever … I don’t know. I was sick of it, it just went on and on, for years afterwards

D: Years?

M: Yes, it went on for a long time. I’d like to go back and get the records actually. It would’ve been at least five appearances at North Sydney court unless I’m mistaken. It felt like five anyway. It was always on at a bad time.

D: What do you mean a bad time?

M: It was always, when I didn’t want to be in North Sydney for some reason. I wanted to go skiing or it was in the middle of the day when I had classes and I was teaching.

D: So it was finished by the end of that year?

M: No, no. I would think that the final decision was made in at least two years from then, could even be longer.

D: So, 1969, after the library sit-ins?

M: Mmm.

D: It continued all through that. I didn’t realise.

M: Yes it was ongoing. I might be wrong about that but, it would be interesting to look back at the records. I know that the whole thing was just a complete pain in the neck.

D: And what did Reg[42] and Vere think of that.

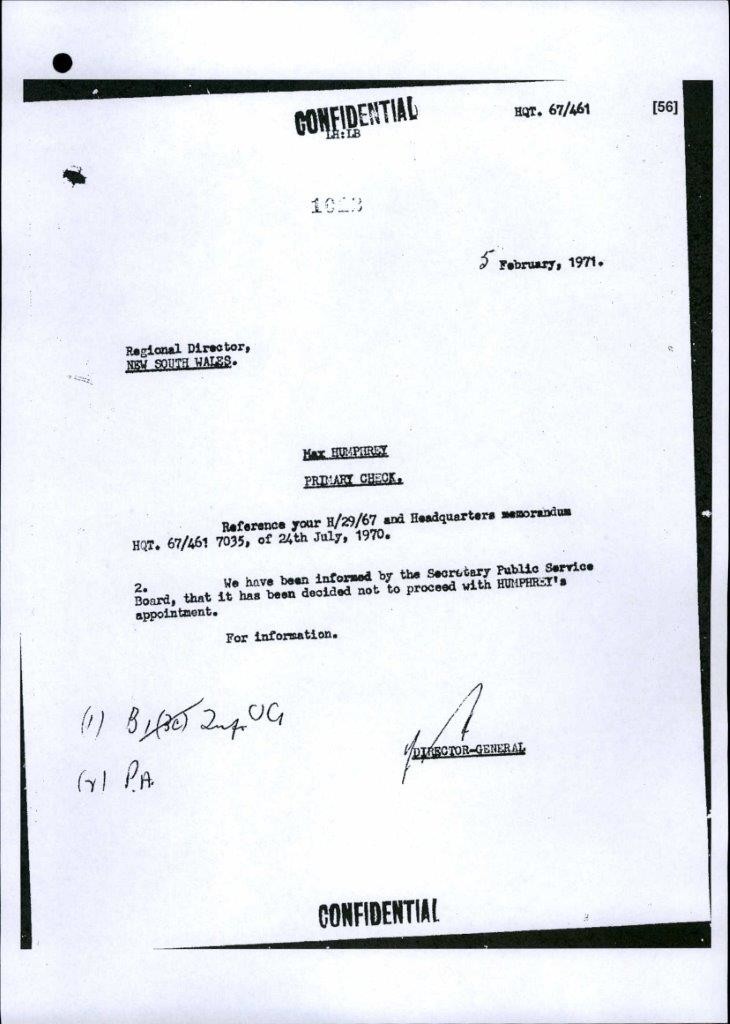

Extract from Max Humphreys’ ASIO file, 1971, showing that the Public Service Board had stopped his appointment to the Commonwealth Public Service. His surname is misspelled.

Extract from Max Humphreys’ ASIO file, 1971, showing that the Public Service Board had stopped his appointment to the Commonwealth Public Service. His surname is misspelled.

M: Well they were pretty supportive. Their friends were, I think they thought it was a bit stupid. What’s his name? The other person who was very supportive I remember who I never would’ve picked was Dr Orban, Paul and Judy Orban. Paul was a medical specialist and his father was a well-known artist and he and Judy were both in KSRC[43].

D: Hromas?

M: No, they lived down, her father was quite a well-known artist[44] in the area and still is. They have his murals on the building. As you come up … They lived on the edge of Longueville. When you come up to Longueville Road round the back on River Road. They’re on that corner when you go round and swoop up there. On the side of it, there’s two buildings there, the one building is dedicated entirely to people who come … He’s gone now … he died many years ago but he’s started a group of artists. They come round there and meet.

D: No.

M: Come on you know him, you’ll know … I’m trying to think if they were Austrian. Paul’s the son. I’m trying to think Paul, Paul …

D: I don’t know him.

M: Come on you know him, he’s, he’s the …

Tape ends.

***

Additional comment by Max Humphreys. In the course of checking the tape’s contents with Max he added these remarks below which I think are worth adding as a postscript to the transcript of our interview.

I have total clarity of events in ACT and Kirribilli House. Almost like videos I’ve watch [sic] a million times. This includes my advising Bob Gould (who for some reason I thought was in charge of both these demos) about what I was going to do and being discouraged by him on both occasions.

Also I think that there was reason to arrest me in ACT since I was on the roof of the now Hyatt hotel which was of course private property. When I paddled around to KH I was not breaking any laws and I believe that my arrest was totally inappropriate and my subsequent bashing was inexcusable. I had of course taken part in other protests without feeling the need to make a separate statement. I felt very strongly that our government should not have been treating Marshal Ky as a dignitary. He was a fascist sympathiser and there was some suggestion that he made a lot of money via sale of smack to GIs. He was a disgusting human being in my opinion.

(Email to Daniela Torsh, 10 October 2016.)

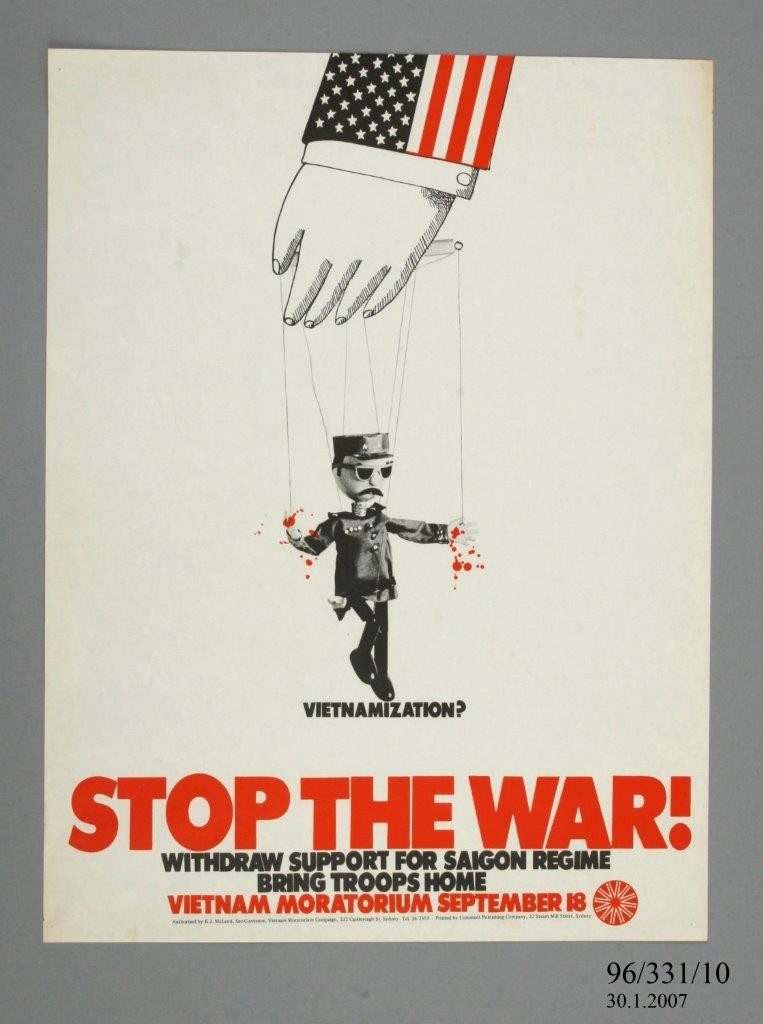

And the war went on. Moratorium poster, September 1970 (Powerhouse Museum 96/331/10/Comment Publishing Company)

And the war went on. Moratorium poster, September 1970 (Powerhouse Museum 96/331/10/Comment Publishing Company)

Notes

[1] This interview was carried out by Daniela Torsh at the Garfish restaurant in Manly over dinner, 30 November 2009. My ex-husband Max contacted me shortly beforehand as he was concerned that an article by Bob Gould misrepresented him and his actions in the anti-war protest movement. I suggested we do an interview to put his position and correct the mistakes.

[2] This was an article written by Bob Gould in 2004. (On Gould, see note 4 below.)

[3] The demonstration was held under the Harbour Bridge in Bradfield Park at Milson’s Point at 11 am on the day Air Vice Marshal Ky arrived from Brisbane with his wife, Saturday, 21 January 1967. A TV news film clip housed at the National Film and Sound Archive shows the reception at Sydney airport by cheering supporters of Ky. The narrator says that, because of police fears of demonstrations, the Ky party was transported by boat across the harbour to the Prime Minister’s official Sydney residence Kirribilli House. The NFSA curator comments that the demonstration was of 10 000 people, half of whom marched to Kirribilli House.

[4] Bob Gould (and his writings are here) was a Trotskyite antiwar activist who ran the Third World bookshop in Goulburn Street, Sydney, for many years. He was a leader of the Vietnam Action Committee, which was active in the mid-1960s against the Australian government’s growing commitment to the Vietnam War. He died in 2011 after falling from a ladder in his Newtown bookstore.

[5] Phillip Deery of Victoria University describes the protest under the Harbour Bridge and Max’s arrest.

[6] Air Vice Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky was the Prime Minister of the junta in South Vietnam. He and his wife, the very glamorous Madame Ky, were official guests of Deputy Prime Minister, William McMahon and his wife, standing in for Prime Minister Harold Holt at Kirribilli House on this visit.

[7] Tom Uren: Federal Labor Party Minister under Gough Whitlam in the 1970s and under Hawke in 1980s. Prominent left-wing anti-war and environmental activist who died in 2015.

[8] Leader of the Labor Opposition in the 1960s, Arthur Calwell was initially pro the Vietnam War but in the mid-1960s changed the ALP position to anti.

[9] Lynne Hyman was a fellow psychology student of Max’s at Sydney University. She worked as a tutor in the Psychology Department at UNSW where Senior Lecturer Dr Alex Carey was a colleague. Carey, a secret Communist Party member, was one of the few academics in Sydney who dared to speak out in the mid-1960s against the then popular war in Vietnam. He had been a keynote speaker at the 1966 national psychology students’ conference at UNSW which Max and Lynne attended.

[10] Mark Aarons, a former ABC radio features journalist, worked for Bob Debus who was NSW Minister for the Environment from 1996 to 2007. Mark is the author of six books, the last, The Family File (2010), being about his family’s four decades of involvement with the Communist Party of Australia and ASIO. Mark’s older brother Brian was a fellow student of ours at Sydney University, an anti-war activist and later editor of the CPA newspaper, Tribune.

[11] Max was arrested in Canberra for pulling down the South Vietnamese flag from the Hotel Canberra roof. This was at a demonstration against Ky on 18 January 1967, a few days before the Kirribilli House demonstration. He appeared in the ACT Magistrates court in Civic on 1 February 1967 and we drove down in our car. He was released on a good behaviour bond for 12 months. We stayed with Dr Bruce MacFarlane, a well-known Maoist political science academic at ANU, who put us up on his couch for the night. I remember waking up on the couch in the living room the next morning and hearing Bruce and his colleague, the historian Humphrey McQueen, in vigorous discussion about some arcane South American political situation. I hadn’t a clue about the topic. The Canberra Times, 2 February 1967, page 4, has a report of the court proceedings.

[12] Max drove to Melbourne in our car and attended a national psychology students’ conference there. I stayed in Sydney working over the summer holidays in a student job at Sydney TAFE in Ultimo.

[13] The boat was a private launch, the Mary D II, owned by a businessman. The NSW Premier, Sir Robert Askin, was Ky’s host on the boat showing him the delights of Sydney Harbour. This according to news reports in the Sydney Morning Herald at the time.

[14] In fact the police were worried about Ky’s safety, so they took him across the harbour, thinking it would be the safest way to get him to Kirribilli House. They wanted to seal off Kirribilli House and keep spectators’ craft at least 100 yards away from the launch. See ‘Master plan to protect Ky in Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 January 1967.

[15] The SMH reported that plans had been made for 1200 men to be on duty for the police, all leave had been cancelled and they would bring cops from the country to make up the numbers.

[16] A small metal rowboat-shaped vessel, which may have oars or an electric motor at the back

[17] Channel 7 and the ABC and Channel Ten were covering Ky’s visit. The ABC cannot find the footage. I haven’t been able to locate any still or television camera material.

[18] Jim Staples was a Sydney left-wing labour lawyer who represented students and radicals frequently in anti-Vietnam demonstrations. Often Staples didn’t charge for his services. He was involved with the Labor Club when he was a student at Sydney University and was in student protests himself in the 1940s. He was a prominent civil liberties lawyer and later became a judge in the Industrial Commission.

[19] Max was a champion swimmer and life saver. As a schoolboy he competed for his high school, North Sydney Boys’, at the State championships and he’d been a surfer and lifesaver at Era beach and Collaroy beach for years.

[20] ‘Sydney threat to kill leader’, Sydney Morning Herald, 19 January 1967. The story was based on an anonymous phone call to a Sydney commercial radio station.

[21] Max’s father’s family was of Irish background.

[22] Max and I were married by this time and we lived at Gordon.

[23] Frank Reginald (Reg) Humphreys (1917-2010) was Max’s father, a chemical engineer who was Chief Chemist for the NSW Forestry Commission.

[24] Dr Max Stephens was the Humphreys family doctor. He lived in Drummoyne in Lyons Road and had his medical practice there.

[25] I was elected to the SRC as a Science representative for women students in July 1967, after Max was expelled by the Proctorial Board in April for organising the sit-ins at Fisher library. Later on, I became NUAUS officer in 1968 but never Education Officer. Law student Phil Smiles was Education Officer when Max was arrested and I think he had brown hair not blonde. Bob Gould wrote in his article that Max was a dreamy blonde which really brings into question the accuracy of Bob’s memories

[26] The demonstration was called for 11am in the morning.

[27] Max was arrested at the Hotel Canberra for pulling down the South Vietnamese flag from the hotel roof. He was charged with being in the hotel without lawful excuse and for offensive behaviour. It was a Crimes Act charge for which he got a $50 bond on 1 February.

[28] Hall Greenland was a prominent anti-war activist at Sydney University in the 1960s and editor of student paper Honi Soit. He was a teacher’s college student at the time. Journalist and editor Greenland was a Greens candidate in the inner west of Sydney at the 2016 Federal election.

[29] SARS was formed by Max after he became outraged that Fisher Library fines were going up. He argued that the students had not been consulted. He said this in an article in the student paper Honi Soit on 5 April and at a Front Lawn meeting of 100 students the same day. The first sit-in was 5 April 1967. Honi carried a report in its 5 April issue on the front page with the heading ‘Uni goons quash free press’. The next morning Max was arrested by University Security and a week later was suspended by the Proctorial Board for 12 months from his Master’s degree in psychology for ‘gross contempt’ of university authority. But the sentence was rescinded after extensive protests by staff and students. Geoffrey Robertson, who was a law undergraduate and President of the Student Representative Council, and Michael Kirby, the Student member of the University Senate, supported him at the Proctorial Board. See Tharunka (UNSW) 26 April 1967. Robertson claims in an unpublished memoir that the incident led to Sir Stephen Roberts, the Sydney University Vice Chancellor quietly resigning a few months later. Robertson also wrote that the ASIO report was evident at the Proctorial Board hearing held by the accusers but was not made available to him or Max.

Demonstration against library fines, University of Sydney, April 1967. Note the conservative dress and the relative lack of women. The student standing at the front is Alan Cameron, who succeeded Geoffrey Robertson as President of the SRC and later became a senior lawyer, Commonwealth Ombudsman and Chairman of ASIC. (Honi Soit, 27 April 1967)

Demonstration against library fines, University of Sydney, April 1967. Note the conservative dress and the relative lack of women. The student standing at the front is Alan Cameron, who succeeded Geoffrey Robertson as President of the SRC and later became a senior lawyer, Commonwealth Ombudsman and Chairman of ASIC. (Honi Soit, 27 April 1967)

[30] According to a report in Honi Soit on 19 April there were 48 students at the first sit-in but by the next one the number grew to 80 on 7 April. A week later there were 175 students at Fisher and even some staff joined in. On 17 April, 200 students were at the sit-in protesting about Max’s expulsion.

[31] The Front Lawn at Sydney University is where all the big meetings and speeches in that era took place. It was in front of the quadrangle tower clock on the eastern side.

[32] Two others were arrested at the sit-ins, a biology tutor Chris Page and Alan Outhred, the Labor Club secretary. They were fined $20 each by the Proctorial Board. Page refused to pay the fine.

[33] Students’ Representative Council. The 1967 President was Geoffrey Robertson, later a famed international human rights lawyer living in London.

[34] It was Maurice May, according to Max’s ASIO file (National Archives A6126, 1400). I finally managed to see this file in mid-2017 after years of repeatedly asking the Archives if they had a file on Max or me. ASIO produced the file a couple of years after I had first asked at the Archives. It is now digitally available for anyone to read, though it is full of mistakes. One glaring example is that they have named the file ‘Maxwell Humphreys’. His name was Max. He never used Maxwell. This is an invention of ASIO, like so much else in the 70-page file. In the file it is clear that ASIO had informants at the university. Many entries in the file listed Max’s multiple misdemeanours when he was arrested for protesting against the Vietnam War and when he was expelled from the University of Sydney.

[35] Gordon Barton was a successful businessman in the transport industry, founding IPEC. He was one of the founders of a new political party, the Liberal Reform Movement, which became the Australia Party, a precursor to the Australian Democrats. Barton became convinced of the anti-war position, even though he had previously been prominent in the Liberal Party.

[36] Max and I separated during this time and I left Sydney at the end of 1968 to work for the National Union of Australian University Students in Melbourne. The ASIO file included material about my time at NUAUS as Education Vice President in 1970 as well as all kinds of personal details, even a hospital admission which they claimed was for poliomyelitis. I never had polio but I did get a lot of cystitis attacks, some very serious for which I may have been admitted to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. Someone at ASIO couldn’t read the doctor’s scrawl!

[37] The ASIO file makes it clear that the NSW Special Branch did keep an eye on Max and other students too. At Sydney University in 1968 there was a huge protest anti-war meeting on the Front Lawn, where a small car, a Mini Minor, was nearly overturned by students in their fury at discovering two police officers, most likely from Special Branch, watching the event.

[38] Arthur Calwell repeatedly called Ky a fascist and in one newspaper story ‘a miserable little butcher’. See ‘Calwell again calls Ky a little butcher’, Canberra Times, 11 January 1967.

[39] ‘Costumes’ was what we called swimming costumes in Sydney at the time. When I moved to live in Melbourne a few years later I was surprised to hear they talked about ‘swimmers’, so I had to learn a new word for ‘costumes’.

[40] Harold Holt.

[41] Actually Max gave the Nazi salute as the police rushed up onto the roof of the hotel to arrest him and he shouted, ‘Here come the wombats to take me away’. See: ‘Demonstrator on bond’, Canberra Times, 2 February 1967.

[42] Reg and Vere were his parents.

[43] The Humphreys were among the founders of the KSRC, the Kosciusko Snow Revellers Ski Club at Perisher Valley.

[44] Desiderius Orban was a Hungarian artist, a Jewish refugee.

North Sydney Court House today (author)

North Sydney Court House today (author)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.