‘Gold, rum but no sign of Ataturk’s minister at Anzac, April-May 1934’, Honest History, 1 December 2015

We return to the provenance of the famous ‘Ataturk words’ of 1934 – the ones commencing ‘Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives’ – with a translation into English of an article by Cengiz Ozakinci in Butun Dunya (Ankara) for October. (Another link for the Turkish version.) We apologise for the delay in providing the translation.

Previous work, including Ozakinci’s earlier articles, can be traced under our ‘Talking Turkey‘ thumbnail. There are links below to key sources, where appropriate. Further work is proceeding in Australia and overseas.

Duchess of Richmond (Trainweb)

Duchess of Richmond (Trainweb)

Ozakinci’s article in English translation is entitled ‘ “1934 Gallipoli pilgrimage” of the former English soldiers who fought in the Canakkale War in 1915 and “Ataturk’s message” ‘. The April-May 1934 pilgrimage on the ship Duchess of Richmond of 700 British veterans, a few of their wives, and an Australian, Captain Henry Wetherell, formerly of the 5th Light Horse, has until now been known to English speakers mostly through the slim book, Gallipoli Revisited, by WE Stanton Hope, published in November 1934, and a few contemporary newspaper articles.

Ozakinci’s article is important, however, because he gives a more detailed picture (using Turkish and English contemporary sources) of the motivations of the Duchess of Richmond pilgrims and how the pilgrims were regarded by the Turks. Ozakinci also knocks on the head one story of how the Ataturk words came about – that they were delivered in a speech by his Interior Minister, Sukru Kaya, to the 1934 pilgrims. Ozakinci shows conclusively that Kaya was not even in the Dardanelles while the pilgrims were there.

Set alongside Ozakinci’s earlier work, particularly his discovery of a speech by Kaya in 1931 using words of Ataturk that were rather different to the ‘famous’ ones, this latest material raises more questions about the provenance of ‘Those heroes that shed their blood …’. Further, it is beyond reasonable doubt that a key sentence in one English version* of the words – about there being no difference between the Johnnies (British soldiers) and Mehmets (Turkish soldiers) – does not date from the 1930s but was concocted in 1977-78 by Ulug Igdemir of the Turkish Historical Society and Alan J. Campbell of the Gallipoli Fountains of Honour committee in Brisbane. (There is a summary of this episode in our research note, section 12.)

We have said many times and repeat again that the ‘Ataturk words’ express a fine sentiment; that should not stop historians from pursuing evidence. That is what historians do. Throwing doubt upon evidence that Ataturk said or wrote the words should be of concern only to those who believe the power of the words comes from their having been said by Ataturk or to those who believe the perpetuation of myths is a higher priority than the pursuit of history.

Summary of Ozakinci’s October article (English version)

Ozakinci’s article covers the key points set out below. The English translation has many more footnotes than the Turkish original.

No treasure hunt

Ozakinci expands a theme – one that is relatively minor in Hope’s book – that a prime motivation of some of the Duchess of Richmond pilgrims in 1934 was to search for caches of gold coins and jars of rum buried on the Gallipoli Peninsula by Allied soldiers in 1915, possibly even a gold mine. The problem with the gold-digging project was that it contravened the Lausanne Peace Treaty of 1923, specifically Section II, which referred to the respect for and maintenance of graves and which prohibited the Ari Burnu or Anzac area being used for commercial purposes. The Richmond treasure hunt would have been a breach of the treaty and the Turkish authorities stopped it happening.

‘Shades of the Rum Corps: “come over here”‘, Norman Lindsay, 1916 (AWM ART50287)

‘Shades of the Rum Corps: “come over here”‘, Norman Lindsay, 1916 (AWM ART50287)

Ozakinci finds evidence that Ataturk himself was in Canakkale on 14 April (directly after the ‘treasure hunt’ story appeared in the London Daily Telegraph) to meet the local Governor, though it is unclear what they discussed. In any event, when the Richmond pilgrims arrived two weeks later, there was no gold-digging, unexpected customs duties were imposed on floral wreaths and the seniority of the Turkish welcoming party was reduced, apparently as a reaction to the Richmond treasure plans. Despite this inauspicious start, however, the visit proceeded, graves were inspected, many wreaths were laid (though one, intended for an Ataturk monument in Istanbul, was taken back to England because the customs duty was just too steep) and one jar of rum was unearthed but accidentally broken and its contents lost.

No minister

Ozakinci’s article sheds further light on the provenance of the ‘Ataturk words’, a matter to which Ozakinci has already given considerable attention (see ‘Talking Turkey‘). Here he critiques some points made by translation expert, Dr Anthony Pym, who speculated that Ataturk’s minister, Sukru Kaya, may well have delivered the ‘Ataturk words’ to the Richmond delegation but have done so in Turkish and the remarks remained untranslated. (The most recent version of Dr Pym’s article; an earlier version.)

Ozakinci in an earlier article discussed Kaya’s proficiency in Ancient Greek as an influence on his rendering of Ataturk’s supposed words and Pym acknowledged this in the later revision of his piece. But the key point is whether Kaya was actually there in 1934. Ozakinci makes these points in his October article:

- If Kaya had been there, he could have spoken to the visitors in either French, in which he was fluent, or English, which he knew.

- If Kaya had been there and had spoken in Turkish, an English translation could have been provided by a Mr Whittall who was travelling with the pilgrims.

- If Ataturk got his officials to come down hard on the gold-digging and the customs duties for the wreaths (including one intended for his own monument in Istanbul) and to wind back the seniority of the welcoming party, he would hardly have been writing conciliatory lines for a speech by one of his ministers.

- The names of the Turkish dignitaries greeting the pilgrims were listed in the press and Kaya’s name was not among them (nor was Ataturk’s).

- Finally and most importantly, during the days that the pilgrims were on the Peninsula, 30 April to 2 May, Kaya was in Ankara (and Ozakinci cites Turkish newspapers to support this).

So this evidence says Kaya was not there. Which brings us back to the photograph in Stanton Hope’s Gallipoli Revisited of the wreath-laying on the Lone Pine memorial during the Richmond visit. Pym in his later piece (pages 14-15) considers the argument that Kaya in 1953 ‘made it up’, that is, made up the Ataturk words that Kaya said were then included in a speech. On the other hand, says Pym, if the 1934 Lone Pine photograph includes Kaya, it allows for the possibility that Kaya made this speech in 1934 – using Ataturk’s words just as he did in 1931. A photograph showing Kaya at Lone Pine would be ‘[t]he one piece of evidence’ against Kaya making it all up 19 years later.

Pym sees the flaws in this hypothesis – notably the lack of newspaper reports of such a speech – but thinks it may be ‘worth entertaining (at least until the photo is discredited)’. The photo has not been discredited. It is definitely a photograph of a ceremony at Lone Pine between 30 April and 2 May 1934 in the presence of the Richmond pilgrims. It just does not include Sukru Kaya.

Honest History needs to apologise at this point to Dr Pym for putting him (and others) on the wrong track regarding the Lone Pine photograph. We did a quick comparison between one of the figures in the Lone Pine photo and two other pictures of Kaya and concluded (see our research note, section 11) that one of the Lone Pine figures was Kaya. If we had looked further, we would have had doubts; for example, the man in the photograph seems to be quite tall, whereas there are photographs of Ataturk (who was somewhere between 168 and 174 centimetres tall) with Kaya and they seem roughly the same height. (It is not clear from Dr Pym’s articles whether he checked the Lone Pine photograph himself; he should have.)

Who then was the Kaya doppelganger? Ozakinci looked more closely at the other Hope pictures than Honest History did and punted for one RD Blackburn, one of the Richmond pilgrims, as the man in the Lone Pine photograph. We think he is correct; more of that below.

The Governor of Canakkale, Sureyya Bey, lays a wreath at the Lone Pine Memorial. RD Blackburn (not Sukru Kaya) is third from the left with the Australian, Captain Wetherell, to his right (Hope, Gallipoli Revisited)

The Governor of Canakkale, Sureyya Bey, lays a wreath at the Lone Pine Memorial. RD Blackburn (not Sukru Kaya) is third from the left with the Australian, Captain Wetherell, to his right (Hope, Gallipoli Revisited)

Provenance and evidence

The upshot of the ‘no minister’ material above is that statements like the following are shown to be lacking in evidence or, indeed, to be nonsense:

- ‘On [the Ari Burnu memorial] are words attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, President of Turkey, sent in 1934 to an official Australian, New Zealand and British party visiting Anzac Cove.’ ‘Sent’ by whom? How? The Richmond party was not official and the available evidence suggests it contained just one Australian (Wetherell) and no New Zealanders. These dubious words are on an Australian government website. The word ‘attributed’ has been inserted since the Honest History articles in April 2015. We contacted the Department of Veterans’ Affairs but they did not have a comment on why the change was made.

- ‘[On the Ari Burnu memorial] are the famous words attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk delivered in 1934 to the first Australians, New Zealanders and British to visit the Gallipoli battlefields.’ This is on the same Australian government website as in the previous reference and the word ‘attributed’ has again been inserted since April. (Again, no comment from DVA as to why.) ‘Delivered’ by whom? How? In any case, the party was not ‘the first’: the parents of George Irwin from New South Wales were at Lone Pine in September 1926, there was the St Barnabas pilgrimage from Britain in the same year (four books were written about that and some Australians who went along made a film about it), British writer and veteran Trevor Allen visited Gallipoli in 1928, Australian journalist JC Waters was there with a party in 1931 and wrote a book about it, and the Imperial War Graves Commission reported in 1931** that cruise ships from Britain, Europe and the United States regularly called at Helles to allow visitors to travel overland to Gallipoli. Thomas Cook’s guidebook to Gallipoli was first published in 1923.

- ‘Underneath Ataturk’s profile [on the Ataturk memorial in Anzac Parade, Canberra] are his famous words of peace, which he dedicated on Anzac Day in 1934.’ This is on an ABC site. Where was Ataturk when he did this? Who else was present? A contemporary report anticipated that Tasman Millington, the Australian warden at Gallipoli, would lay a wreath there on Anzac Day 1934 but there was no hint that Ataturk would join him.

- ‘Referring to the Anzac troops at a Gallipoli dawn service in 1934 [Ataturk] said: “Those heroes …” ‘. A dawn service on what date? Certainly not on 25 April, which was before the Richmond pilgrims had even arrived at Gallipoli. This is on the website for the National Anzac Centre at Albany, WA, a project which received a good deal of Commonwealth money.

- ‘At a dawn service in 1934 in Gallipoli referring to the ANZAC troops, [Ataturk] said: “Those heroes …” ‘ . This is on a website containing a database of Australian memorials and monuments. It is possibly copied from the source in the previous reference.

- ‘Of Ataturk’s many famous speeches, in 1934 he paid tribute to the fallen soldiers during the Gallipoli campaign and comfort to their mothers. The memorial at Anzac Cove incorporates an extract from this speech: “Those heroes …” ‘. This is from the website of the Gallipoli Memorial Club, Sydney. Was this alleged speech given at the ‘dawn service’ referred to in the previous two entries or somewhere else?

- ‘Kemal Ataturk … wrote these words to be spoken by his Interior Minister to a delegation from the Imperial War Graves Commission which was visiting Turkey: “Those heroes …” ‘. This by David Fricker, President, International Council on Archives and Director-General, National Archives of Australia, to a conference in Istanbul, March 2015. When was this delegation? Is the Director-General confusing it with the Richmond delegation, which included some members of the IWGC?

- ‘Many Turkish memorials stand on the peninsula. Inscribed on several are the words of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, spoken in 1934: “Those heroes …” ‘. This is from the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, London, the renamed IWGC. Again, when and where in 1934? Spoken just to Kaya, in a speech, or at a dawn service? Is the strongest support for the idea that these words came from Ataturk in 1934 the belief that such powerful words must have come from a powerful man or simply the fact that other people have said this is where and when the words originated so it must be right? But then why do the versions differ so much?

Design by Matthew Harding for Australia-Turkey Friendship Memorial, Melbourne, 2015 (Sydney Morning Herald)

Design by Matthew Harding for Australia-Turkey Friendship Memorial, Melbourne, 2015 (Sydney Morning Herald)

Bottom line so far

Let’s try to link these examples to what we know already, as set out in ‘Talking Turkey‘. A standard definition of the term ‘hearsay’ is ‘information received from other people that cannot be substantiated’. The synonyms are ‘gossip’ and ‘rumour’. Ulug Igdemir in 1978 (research note, section 12) accepted information received by Dunya‘s Yekta Ragip Onen in 1953 from Sukru Kaya (died 1959) who claimed to recall the words of Ataturk (died 1938) from (perhaps) 1934.

Neither Onen nor Kaya give a date for Ataturk’s supposed remarks; the date 1934 comes from Igdemir though he does not specify when in that year. Pym suggests some historians say Kaya gave the speech on 18 March 1934, the anniversary of the Battle of Canakkale. The Turkish Embassy in Canberra makes a similar claim and we have asked the Embassy for evidence with no response to date. (We are pursuing this line of inquiry further.)

In Kaya’s 1931 speech he says he is drawing upon ‘an anecdote’ from Ataturk. This speech clearly distinguishes ‘the invaders’ from ‘the heroes’ and declares that the sacrifice of the latter was more worthy of appreciation. In the 1953 interview Kaya recalls receiving from Ataturk detailed instructions about what to say, including words about the Turkish defenders’ bravery, followed by a piece of paper on which Ataturk had written more words for Kaya to use.

Then, we know from contemporary newspaper reports that the 1931 speech was delivered at the Mehmets (Mehmetcik) Monument at Kemalyeri. In the 1953 interview Kaya said the speech he was recalling was delivered ‘by the side of the Mehmetcik monument’. It sounds like Kaya in 1953 was recalling his 1931 speech; it is only Igdemir who dates the speech Kaya recalled in 1953 as being given in 1934. But we have the text of the 1931 speech and it does not include the words Kaya recalled in 1953 – the words that (apart from the Igdemir-Campbell addition of the Johnnies and Mehmets comparison) have become famous.

So far we have: a speech in 1931 but the words are wrong; no evidence of a speech in 1934. But, if Kaya could not have given a speech to the Richmond pilgrims – because he wasn’t there – was there another Kaya speech in 1934 (18 March, perhaps?) that, as in 1931, Ataturk helped him with and that, again, was delivered next to the Mehmetcik Monument? That sounds implausible. We agree with Pym’s warning that we ‘should not take Sukru Kaya’s account [in 1953] as gospel truth … Kaya could have made it up.’ (Kaya was subject to a number of personal and political pressures in 1953 that may have pushed him towards invention or embellishment: see the last four paragraphs of section 12 of our research note.)

Readers may well be confused by all this. (History isn’t meant to be easy.) There was a string of hearsay and confusion, reconstruction and guesswork long before any of the eight examples quoted above. Perhaps it is no wonder that these sources have settled for vague provenance, relied on ‘what he/she said’, made a wild guess at when the words might have been said (the ‘dawn service’ option), concluded that such nice words couldn’t possibly be a fake, or simply didn’t care.

Honest History had an exchange earlier this year with the City of Hume in Victoria, which was proposing to erect an Ataturk memorial plaque containing the famous words. Although at one point the City did refer to words ‘attributed to Ataturk’, its parting shot was to ‘point out that these same words have been widely used by a number of military, State and Federal Government representatives’. Honest History responded that ‘it diminishes the act of commemoration to go on using the words unqualified, regardless of how many times they have been used previously by others. Persistence does not rectify errors but it certainly props up myths.’ Anthony Pym made a similar point, after listing some of the many memorials bearing the famous words: ‘This is a paroxysm of monuments and plaques, all reinforcing each other, with a certitude that creates its own history’.

Reputable historians would not accept ‘Ataturk 1934’, the typical formulation, as adequate evidence of provenance; they would even be wary about settling for ‘attributed to Ataturk’, the variation that appears in some sources. There is still work to be done to establish the provenance trail from Ulug Igdemir’s creative work of 1978 to the received version of 1985 and since. For the time being, we simply note the words of Article 134 of the Turkish Constitution of 7 November 1982, which set up the Ataturk High Institution of Culture, Language, and History, incorporating Igdemir’s Turkish Historical Society, ‘to produce publications and to disseminate information on the thought, principles, and reforms of Ataturk, Turkish culture, Turkish history, and the Turkish language’.

Meanwhile, Honest History will gladly accept and publish any evidence other researchers provide to us. We say yet again that provenance – who said what, when and where – is separate from the issue of how the words are received. The latter is influenced by culture, tradition, habit and what the receiver wants to believe. Provenance and evidence is the arena of history; the rest is the arena of mythology and religion – and comfort. The two arenas can co-exist but they need to be distinguished. We endorse Pym’s remark that the ‘Ataturk’ paragraph, whoever said or wrote it originally, ‘touches the shared commonness of suffering, a basic level at which one culture can grasp something of another’s experience’. (Pym’s most recent reworking discusses the concept of ‘transcendence’ in translation. It is hard going but it is relevant to this point.)

Who was RD Blackburn, the gentleman in the photograph?

Ozakinci’s article includes a cropped photograph (taken from Hope) of Blackburn in 1934 as he emerges from his former dugout on the Gallipoli Peninsula. He looks happy enough.

Blackburn’s full name was Richard Dennis Blackburn. While his service record (behind a pay-wall on Find My Past) shows that he did not enlist in the Royal Naval Division (Hope’s unit) until 1917 and lost his left hand after that – the uncropped photograph in Hope clearly shows the stump – he certainly seems to have been in the Dardanelles in 1915. Hope refers in his book to ‘Blackburn, whom I knew well in the war days’ (p. 52) and mentions Blackburn’s missing hand; it seems unlikely that Hope would have misremembered Blackburn being there in 1915. There is a copy of Hope’s book in the Imperial War Museum***, signed by the author and given by Blackburn to a friend, James Beal, in November 1934.

Blackburn’s full name was Richard Dennis Blackburn. While his service record (behind a pay-wall on Find My Past) shows that he did not enlist in the Royal Naval Division (Hope’s unit) until 1917 and lost his left hand after that – the uncropped photograph in Hope clearly shows the stump – he certainly seems to have been in the Dardanelles in 1915. Hope refers in his book to ‘Blackburn, whom I knew well in the war days’ (p. 52) and mentions Blackburn’s missing hand; it seems unlikely that Hope would have misremembered Blackburn being there in 1915. There is a copy of Hope’s book in the Imperial War Museum***, signed by the author and given by Blackburn to a friend, James Beal, in November 1934.

Blackburn cropped (Butun Dunya)

In any case, whether or not Blackburn was there in 1915, he was certainly there in 1934, standing on the steps of the Lone Pine Memorial, with his hat somehow held under his mutilated arm, discreetly behind his back, and looking just a little like Sukru Kaya. Again, our apologies to him, to Anthony Pym and to readers for our error.

In any case, whether or not Blackburn was there in 1915, he was certainly there in 1934, standing on the steps of the Lone Pine Memorial, with his hat somehow held under his mutilated arm, discreetly behind his back, and looking just a little like Sukru Kaya. Again, our apologies to him, to Anthony Pym and to readers for our error.

Kaya in formal pose (Wikipedia)

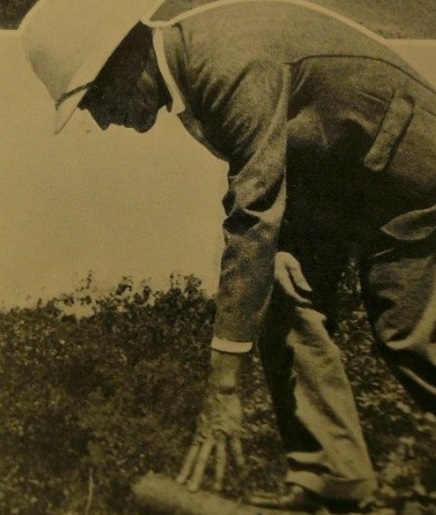

Captain Wetherell picks up an unexploded shell on the site of his old trench at Lone Pine (Hope, Gallipoli Revisited). Wetherell is the only Australian mentioned in contemporary accounts of the Richmond pilgrimage, such as a note in the Times of 4 May 1934, Hope’s article in the Sydney Morning Herald of 7 July 1934 and a plug for Hope’s book in the Australasian of 27 April 1935. He also appears in the Lone Pine photograph, standing to RD Blackburn’s right. During the Gallipoli evacuation, Wetherell is said to have come up with the idea of shining searchlights from ships offshore to prevent the Ottoman defenders from seeing the departing troops. Wetherell lived in Brisbane after the war, gave at least one talk on radio in 1934 about his wartime experiences and his tour that year and wrote a newspaper article about the Palestine leg of the tour. He co-wrote a history of the 5th Light Horse, was active in rowing circles and died in 1948. (Trove)

Captain Wetherell picks up an unexploded shell on the site of his old trench at Lone Pine (Hope, Gallipoli Revisited). Wetherell is the only Australian mentioned in contemporary accounts of the Richmond pilgrimage, such as a note in the Times of 4 May 1934, Hope’s article in the Sydney Morning Herald of 7 July 1934 and a plug for Hope’s book in the Australasian of 27 April 1935. He also appears in the Lone Pine photograph, standing to RD Blackburn’s right. During the Gallipoli evacuation, Wetherell is said to have come up with the idea of shining searchlights from ships offshore to prevent the Ottoman defenders from seeing the departing troops. Wetherell lived in Brisbane after the war, gave at least one talk on radio in 1934 about his wartime experiences and his tour that year and wrote a newspaper article about the Palestine leg of the tour. He co-wrote a history of the 5th Light Horse, was active in rowing circles and died in 1948. (Trove)

‘Wreaths laid on Lone Pine Cemetery Memorial which were mostly relics of the 1934 Ex-Service Mens’ Pilgrimage. (Donor Department of Defence, Melbourne)’ (AWM H16824)

‘Wreaths laid on Lone Pine Cemetery Memorial which were mostly relics of the 1934 Ex-Service Mens’ Pilgrimage. (Donor Department of Defence, Melbourne)’ (AWM H16824)

* A version of the words without a reference to Johnnies and Mehmets appears occasionally, for example, in the writings of Peter FitzSimons in 2013 and 2015.

** Update 3 December 2015: Honest History checked IWGC reports right through the 1930s and found reports of such cruise ship visits almost every year, though the Commission did not report the visit of the Richmond pilgrims in 1934 – even though the group included some IWGC members travelling privately – or any notable events associated with it (Sixteenth Annual Report of the Imperial War Graves Commission 1936, HMSO, London, 1936, p. 36; the Commission’s reports lagged – this one reported the year ended 31 March 1935). Interestingly, though, the 1938 report, covering the year 1936-37, did report a private visit to Gallipoli by King Edward VIII (Eighteenth Annual Report of the Imperial War Graves Commission 1938, HMSO, London, 1938, p. 30). Notable events were mentioned amid the routine and repetitive remarks about weather and planting of flowers around graves. There are frequent mentions also of the co-operation extended by Turkish authorities in the maintenance of graves; one would expect that a magnanimous gesture or remarks by a senior Turkish official like Kaya (let alone Ataturk) would have rated a line.

*** Honest History thanks Carrie Giunta of the No Glory in War and Stop the War websites for her research at the Imperial War Museum.

What an engrossing work of deductive reasoning, Holmes ……