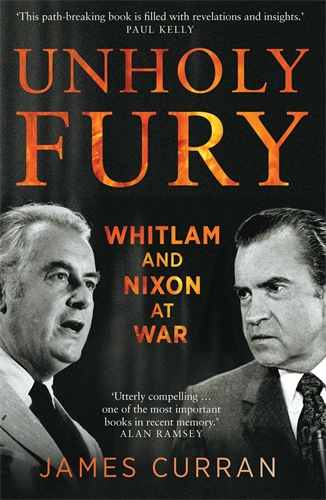

‘No-go zones: review of James Curran’s Unholy Fury’, Honest History, 15 June 2015

Alison Broinowski reviews James Curran, Unholy Fury: Whitlam and Nixon at War

Has anyone else noticed that the world has a growing number of places that are off limits, people who can’t leave the place they’re in, and events that can’t be explained? I call these no-go zones, and if they proliferate at the present rate, maybe they’ll join up and that’s how the world will end. The geographic ones I’m thinking of are Chernobyl and Fukushima, various minefields and defoliated areas in Indochinese countries, and low-lying islands facing sea-level rise; the personal ones include Julian Assange, Edward Snowden, and Chelsea Manning, the people of Gaza, and millions of refugees; and among the topical ones are the deaths of John F. Kennedy, Yasser Arafat, and Dr David Kelly, the Hilton Hotel bombing, the Oil for Food scam, 11 September 2001, and, of course the dismissal of Gough Whitlam.

Has anyone else noticed that the world has a growing number of places that are off limits, people who can’t leave the place they’re in, and events that can’t be explained? I call these no-go zones, and if they proliferate at the present rate, maybe they’ll join up and that’s how the world will end. The geographic ones I’m thinking of are Chernobyl and Fukushima, various minefields and defoliated areas in Indochinese countries, and low-lying islands facing sea-level rise; the personal ones include Julian Assange, Edward Snowden, and Chelsea Manning, the people of Gaza, and millions of refugees; and among the topical ones are the deaths of John F. Kennedy, Yasser Arafat, and Dr David Kelly, the Hilton Hotel bombing, the Oil for Food scam, 11 September 2001, and, of course the dismissal of Gough Whitlam.

Historians set themselves the task of stopping the spreading pollution of no-go zones by picking through the mullock heaps for fragments of truth. James Curran is such a historian. Having earned extensive access to grants, to national archives in Washington, London, and Canberra, and to newly declassified documents, he has produced a thoroughly documented yet highly readable study that challenges past and present views of the Australia-United States relationship. It comes only a few months after Malcolm Fraser’s Dangerous Allies, and the two books should be read together.

Dr Curran’s begins in 1953 and ends in 1975, with concluding comments on the years that followed. For Australia in 1972, it was time: Prime Minister Whitlam responded to the electorate’s impatience for change, completed the withdrawal from Vietnam, questioned the scope of the alliance, and demanded accountability from the US about the bases. President Nixon, in contrast, still fighting the Cold War, and desperate to keep allied forces in Vietnam, ostracised Whitlam as a dangerous Socialist – even though both leaders recognised China. As Dr Curran shows, they both oscillated: Whitlam between restraint and outrage, while seeking to remain diplomatic; Nixon between ignoring and confronting Australia’s new leader, while vilifying him to others.

Some had not noticed that it was time. Antiquated ideas about Australia prevailed in the State Department and the White House, while the advice of better-informed US officials was often ignored. Equally out of date were those Australians who believed the US would always defend us, which, as Nixon’s Guam Doctrine asserted, it would not, unless it was in America’s interests. The US threatened to back away from the alliance, while Whitlam sought to redefine it in terms of greater self-reliance.

Central to the strained relationship were the CIA and the bases in Australia. The ALP Left would happily have closed Pine Gap but, for the US, the bases were indispensable. Whitlam demanded an admission about the CIA’s role in the bases and accused the Opposition of being subsidised by the CIA. Days later the Governor-General dismissed him. Brian Toohey, John Pilger, Christopher Boyce and others have detected dirty tricks in the dismissal, involving Sir John Kerr and Defence Secretary Sir Arthur Tange, all of which Vietnam historian Peter Edwards denies. Whitlam’s statement in Parliament on 4 May 1977 on how intelligence services collaborate behind their governments’ backs deserves a contemporary re-reading. But those hoping for a definitive answer from Dr Curran’s book about the dismissal will be disappointed. For all the material at his disposal, and with Whitlam, Fraser, Kerr and Tange all dead, only conspiracy theories are left.

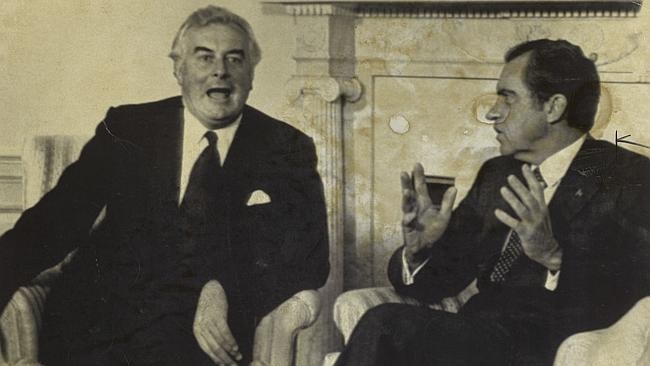

Nixon and Whitlam at the White House, July 1973 (The Australian)

Nixon and Whitlam at the White House, July 1973 (The Australian)

Although Dr Curran suggests that the Australia-US relationship has developed and matured, Curran’s own account shows that Whitlam’s successors learnt from the events of 1975 and stood up to Washington less and less. Far from banishing the bases, we now have Marines on the ground in the Northern Territory; drone attacks in the Middle East get their coordinates from Pine Gap; we are allowing Cocos Island to be turned into another Diego Garcia; we are taking the US side against China in the Eastern Sea; we are cooperating in Star Wars; we won’t resist nuclear-armed aircraft and ships entering Australia; we might even take US nuclear waste if they ask us to. We don’t ask many questions, and we get fewer answers, particularly about the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Large parts of Australia’s physical, personal, and intellectual territory are already no-go zones.

©Alison Broinowski 2015

Alison Broinowski is a former diplomat who has written many books and articles. Alison Broinowski is Honest History’s vice president, a member of Australians for War Powers Reform and the co-editor of a book shortly to be published, How Does Australia Go to War?, which includes chapters from HH distinguished supporters, John Menadue and Douglas Newton, secretary David Stephens, and other contributors.