John Myrtle*

‘Australian armed robbers Russell Cox and Ray Denning: it was a different world then’, Honest History, 11 September 2020

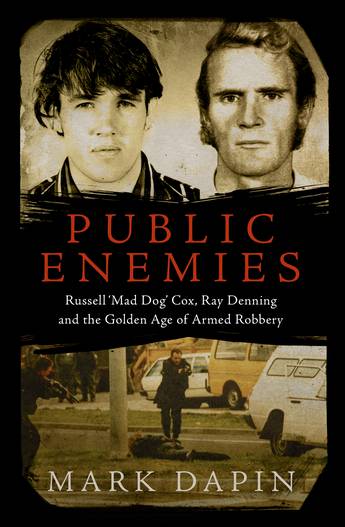

John Myrtle reviews Mark Dapin’s Public Enemies: Russell “Mad Dog” Cox, Ray Denning and the Golden Age of Armed Robbery

Their story is one of violence and crime, but it is also about the unimaginable horrors that young boys faced when condemned to “institutions” in the 1960s, and the terrible conditions in Australian jails in the 70s and 80s.These were the hells where a whole generation of armed robbers was forged.[1]

That is the introduction to Public Enemies, by Mark Dapin, a racy and engaging story of armed robbery in Australia, based on the lives of Ray Denning and Russell Cox. Dapin’s treatment says a lot about how Australians relate to the careers of violent criminals, from Ned Kelly till perhaps even now. We view these men (and women) with a mixture of horror and fascination: their world and the reasons for their fame are hard to fathom for us today. In some ways, Cox and Denning are more like Kelly than they are like us.

That is the introduction to Public Enemies, by Mark Dapin, a racy and engaging story of armed robbery in Australia, based on the lives of Ray Denning and Russell Cox. Dapin’s treatment says a lot about how Australians relate to the careers of violent criminals, from Ned Kelly till perhaps even now. We view these men (and women) with a mixture of horror and fascination: their world and the reasons for their fame are hard to fathom for us today. In some ways, Cox and Denning are more like Kelly than they are like us.

Ray Denning was the child of Jack (Jack the Hat) Denning and his wife, Patricia. Jack was an incompetent petty criminal and a complete failure as a father; as a child he had been committed to the Gosford Farm School, later renamed the Mount Penang Training School for Boys. In April 1961, Patricia committed suicide at her home, witnessed by 10-year old Ray. Ray struggled at school and soon drifted into petty crime. Like his father, he went to Mount Penang, which he described as the start of his downfall, with ‘nothing but hard work and sadistic treatment from the officers’.[2]

Russell Cox was born Melville Peter Schnitzerling in Brisbane in 1949. His parents separated when he was young and he became involved in petty crime, first in Sydney, later in Brisbane. In 1962, he was declared a ward of the state and admitted to the newly opened Boys Town at Beaudesert, south of Brisbane.[3] A year later he absconded but was eventually sent to the Westbrook Farm Home for Boys, ‘the most feared in [Queensland’s] alarming system of juvenile care’.[4]

So, neither Denning nor Cox had supportive parents and at a young age each had experienced the brutality of poorly staffed and uncaring juvenile agencies which acted as graduate schools for criminal careers.

Not many “professional” offenders begin their criminal careers as armed robbers, although a career path was quickly established. They begin by stealing bicycles, before they moved on to cars. They were then incarcerated in boys’ homes, where they toughened up, built wide-ranging contacts, formed the cores of gangs and learned criminal ways.[5]

From the 1970s and after, Denning and Cox became notorious for their crimes, robbing banks and armed security vans, and for their capacity to thumb their noses at authority, refusing to be beaten down by the restrictions and brutality of prison life. Prisoners had all kinds of grievances. Many were jailed based on unsigned confessions or ‘verbals’ and, if police did not believe the verbal was sufficiently convincing, they would also load up the suspect with weapons or other material evidence.

Coincidentally at this time, a number of young activists were also experiencing prison life, punishment arising from political activism such as protests against the Vietnam War and opposition to conscription and, much to the irritation of politicians, these activists became aware of the appalling conditions and practices of prison life. Campaigns by anarchists and other activists were not new, but on occasions were quite bizarre. For instance, in Sydney in 1959, two escaped prisoners, Simmonds and Newcombe, had killed a warder at Emu Plains Prison Farm and were celebrated by the libertarian Sydney Push for their audacity and bravery – views totally at odd with public opinion.[6]

By 1975, both Denning and Cox were at Grafton. Later, Cox was transferred to Katingal, a fortress-like facility outside the main wall at Long Bay. The worst of the worst were incarcerated at Katingal, which was supposedly escape-proof.

Cox shared a wing at Katingal with Denning and other former associates and was already planning his next escape. The plan was known to other prisoners, including Denning, and involved sawing through bars with a hacksaw. On the night of the escape bid, however, the other prisoners were away from Katingal attending court at Maitland and Cox alone made good his escape. Not only did Cox remain free, but in the following year he attempted to break back into Katingal to free his friends.[7] He was involved in armed robberies in both Victoria and Queensland and he was believed to have lived overseas until the early 1980s.

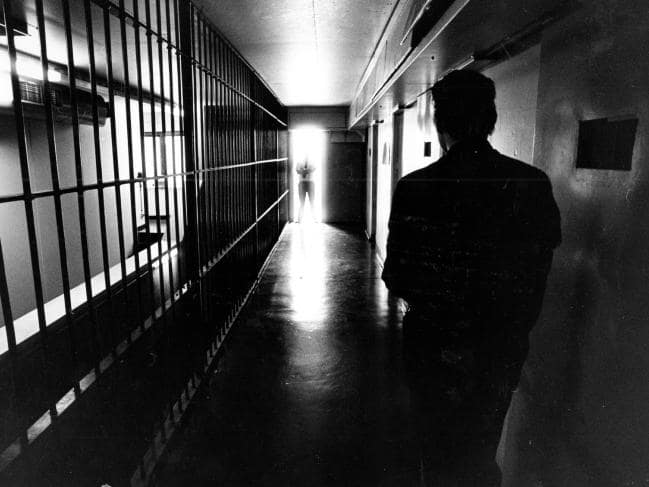

Katingal (Daily Telegraph)

Katingal (Daily Telegraph)

Diverting from the lives of Cox and Denning, the book provides an interesting profile of New Zealand-born criminal Brett Collins. Collins was raised in a middle-class family and his youthful misbehaviour had led to incarceration in a juvenile borstal. In 1968 he borrowed the identity of a flatmate and moved to Sydney. Three years later, he borrowed a shotgun and attempted to rob a bank. He was soon arrested, bashed by the police, and sentenced to a long prison sentence. In the words of Public Enemies, ‘in jail, the frenetic and inquisitive Collins became an organiser, a troublemaker. He taught himself the law and also how to be a prisoner’[8] and, when prisoners won the right to elect prison committees, Collins became the committee chair.

In the 1970s and 80s, the high drama and violence of armed robbery, together with the fate of prison escapees, provided fodder for the mass media, with journalists competing for the best coverage. In 1980, Ray Denning escaped from Grafton, the first successful jailbreak for him, and the first time a prisoner had broken out of Grafton. In spite of frantic police pursuit, Denning’s antics, once free, with support from middle-class activists, were closely followed by journalists, and a youthful Michael Robotham, working for Sydney’s Sun newspaper, achieved a number of scoop interviews with Denning.

Denning at first remained in Sydney, accommodated in safe houses organised by supporters, but by August 1981 he had moved to Brisbane and linked up with Russell Cox. In September, they robbed the armoured truck delivering the payroll to the Railway Centre in Brisbane, with the haul of $327 000 the biggest payroll robbery in Queensland’s history. Tipped off by an informer, NSW Police finally arrested Denning in Sydney in November 1981.

Denning had changed, however: he was addicted to heroin and in 1986 he became a registered informer for NSW authorities. He was classified as a medium-security prisoner, but in July 1988 he escaped from Goulburn and managed to catch up with Cox in Melbourne. The two were caught while trying to rob a security van in a shopping centre. In February of the following year, they were sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for the attempted robbery, but it soon became clear that Denning had rolled over and had informed on a number of his associates, including Cox.

Several reasons have been suggested for Denning’s betrayal of Cox. Some said jealousy – Cox was a more mature, smarter criminal and had managed to stay free for 11 years after escaping from prison. Others said Denning resented the fact that Cox had escaped from Katingal without him. The beginning of the end for Denning occurred when his life sentence in April 1991was redetermined. He was included on the methadone program at Long Bay and on 21 April 1993, equipped with a new name and 24-hour police protection, he moved into a safe house.

Shockingly, two weeks after Denning’s release, he was removed from the witness protection program and, early in the morning of 10 June 1993, he died from a heroin overdose.[9] Meanwhile, there were a number of charges against Russell Cox listed to be heard in different jurisdictions, but some of these fell through.[10] Imprisoned in NSW, Cox married his chief supporter, Helen Deane, while in prison and on 8 December 2004 he was released from Grafton jail.

The strength and value of Public Enemies is that it covers the villains, rogues, reformers and heroes of the era. Among the police in New South Wales, Roger Rogerson is reviled, not only for his murderous violence, but also for having regularly framed suspects for crimes that they had not committed. The inscription for Rogerson’s photo in the book suggests that he was ‘dashingly brave’, which is not this reviewer’s assessment.

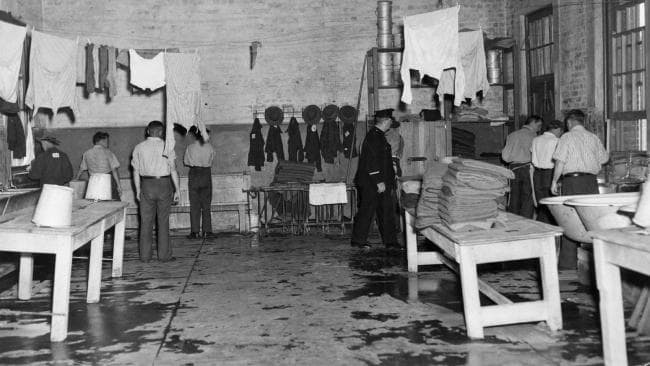

Long Bay laundry chores c. 1960s (Daily Telegraph)

Long Bay laundry chores c. 1960s (Daily Telegraph)

And thinking of villainous acts, one is reminded of the impact of armed robbery over many years with bank officers and security officers gunned down, bank customers taken hostage and terrorised, taxi drivers robbed, shopkeepers brutalised, and families terrorised in their homes. Quite apart from the death and injury, the psychological damage was incalculable and, for many, lasted for a lifetime.

Among the armed robbers, Brett Collins has been an important reformer. In 1982, the Australian government had failed in its attempt to have him deported back to New Zealand and for the past thirty years he has been a notable advocate for prisoners’ rights and penal reform. The 1976 Royal Commission of the NSW Government into the Department of Corrective Services, with Justice John Nagle as Commissioner (reporting in March 1978), provided an opportunity for wholesale reforms for the prison service in that State.

Ultimately, there was considerable change in the 1990s, with banks installing armed guards, security screens and CCTV, and ceasing to handle large amounts of cash as people turned to credit cards, and wages and salaries were paid by direct bank transfer. Robbers’ targets had become much more difficult propositions.

Public Enemies is strongly recommended. It is not only a gripping and engaging social history, but will also be a useful reference point for other writers and researchers.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He has produced Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references, and has written a number of book reviews for us (use our Search engine), a study of industrial action in the Sydney media industry in 1966-67, an article on Edward St John QC, and the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

[1] Public Enemies, Cover.

[2] Ibid, 44.

[3] The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (2017) identified 219 claims of historic child abuse levelled against the staff of Boys Town, Beaudesert. See Public Enemies, 33.

[4] Public Enemies, 36-37.

[5] Ibid, 63.

[6] Anne Coombs, Sex and Anarchy: The Life and Death of the Sydney Push. Viking, Melbourne, 1996, 135-36,

[7] Ibid, 139-140.

[8] Ibid, 150.

[9] Ibid, 325-26.

[10] Ibid, 341.