John Myrtle*

‘”A man of intriguing contradictions”: Edward St John and the South Africa Defence and Aid Fund’, Honest History, 17 May 2019

Edward St John QC, a prominent Sydney barrister and human rights campaigner, was a founding member and the early chairman of the South Africa Defence and Aid Fund (SADAF), the first anti-apartheid organisation in Australia. The Fund was established as a branch of the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF) with the aim of providing legal defence and financial support for the victims of apartheid. I will argue in this paper that St John was a divisive figure whose political ambition, conservatism and strong anti-communism limited the effectiveness of SADAF during its formative years.

Edward St John was born in 1916 and was educated at the Armidale High School and the University of Sydney. He was admitted to the NSW Bar in 1940 and served in the 2nd AIF in the Middle East and New Guinea. After the war he was a prominent figure in the Sydney Bar, taking silk in 1956. St John was an internationalist with a strong commitment to human rights, including a close association with the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ). He had attended the inaugural meeting of the Australian section of the ICJ, held in Sydney on 8 August 1958 and was elected as Secretary, and later President of the Australian section from 1961.

South Africa’s National Party government was elected in 1948 with a domestic program of apartheid or separate development. This led to profound changes within South Africa for the non-white population. Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, who was minister for native affairs from 1950 and later prime minister, was, in the words of Nelson Mandela, ‘the chief theorist and master builder of grand apartheid’.[1]

Responding to apartheid’s discriminatory and oppressive policies, the formation of the Congress of the People in 1955 and the drafting of a Freedom Charter were momentous events. The Charter called for the abolition of unjust laws, the right to vote, and the right to stand for election to public office. This was a highly significant movement for democratic change, but the South African government responded in a dramatic and brutal manner. On 5 December 1956, 156 persons were arrested in dawn raids and were charged with high treason. In the words of one writer, ‘almost the whole of the avant garde of South Africa’s liberation movement was crowded into the cells of the Johannesburg Fort’.[2]

The preliminary examination in the subsequent legal proceedings extended for more than a year before the accused were committed for trial. In 1959, Edward St John was invited by the British branch of the International Commission of Jurists to attend the second stage of the trial as an ICJ observer.[3] Subsequently, the majority of those tried were discharged and only in March 1961 were the remaining defendants found not guilty.

During and after the long-running treason trial, the implementation of apartheid policies resulted in widespread upheaval and unrest in both rural and urban areas of South Africa; large groups of the population were removed from their homes and repressive pass laws were introduced. Opposition to these moves reached a head in 1960, when the Pan-Africanist Congress, an off-shoot of the African National Congress, launched an anti-pass campaign. On 21 March 1960, armed police confronted a peaceful campaign rally at Sharpeville; 69 people were killed and more than 300 injured by police bullets. Many of these victims were shot in the back, fleeing the violence. In the uproar that followed the Sharpeville massacre, on 31 March 1960 the Government declared a state of emergency and more than 1800 people were arrested and held without trial.

Both the defendants in the extended legal proceedings of the treason trial, and those detained after the Sharpeville massacre, required financial support for their families and engagement of the best possible defence lawyers. In London in 1956, a leading Anglican cleric, Canon John Collins, read reports of the treason trial arrests and initiated a defence fund, which became known as the International Defence and Aid Fund (IDAF).[4]

The Sharpeville massacre was a significant event in South African history, not only for South Africans but also for supporters of human rights in other countries, who became aware of the violent and oppressive impact of the laws and policies of the apartheid regime. The Australian reaction to Sharpeville included protests, considerable press coverage and parliamentary debate in which conservative politicians offered little sympathy for the victims of the shootings. One consequence for Australia and other Commonwealth countries was that many political activists in South Africa opted to migrate, rather than live in an oppressive political environment. A number of those who arrived in Australia from South Africa in 1961 were to be key figures in the formation of the South Africa Defence and Aid Fund (SADAF).

The decision to form SADAF was made on 16 April 1963 at a gathering at a private home in Sydney, the residence of David and Rhona Ovedoff, who were among those who had emigrated from South Africa in 1961. As well as the Ovedoffs, there were three other South African emigres attending who would have a significant impact on SADAF’s work, Derick Marsh and John and Margaret Brink.

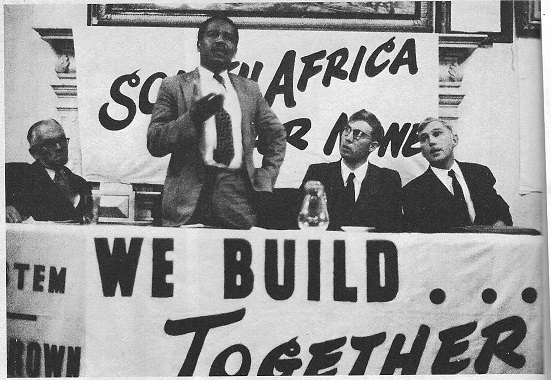

Alan Paton, Derick Marsh and Peter Brown listening to Jordan Ngubane at a Liberal Party meeting, Pietermaritzburg, 1958 (Alan Paton, Journey Continued: an Autobiography, Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 64; photo courtesy Peter Brown)

Alan Paton, Derick Marsh and Peter Brown listening to Jordan Ngubane at a Liberal Party meeting, Pietermaritzburg, 1958 (Alan Paton, Journey Continued: an Autobiography, Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 64; photo courtesy Peter Brown)

All five of these emigres had been members of the Liberal Party of South Africa, a reformist non-racial political party formed in May 1953. Derick Marsh and John Brink were among those detained in 1960 after the Sharpeville emergency. Derick Marsh, the Pietermaritzburg chairman of the Liberal Party, was held in Pietermaritzburg Prison; not only a difficult time for Marsh, but also for his wife Nicola with two young children. Marsh had been employed as a lecturer in English at the University of Natal and, after his release from prison, he decided to emigrate to Australia. He was appointed to a senior lecturer’s position at the University of Sydney and, together with his family, flew out of South Africa on 31 December 1960.[5]

John and Margaret Brink were also active members of the Liberal Party of South Africa. John was chairman of the Party’s Pretoria branch and Margaret became the first Liberal Party election candidate to stand against a Uniting Party member. She and her twin sister, Elizabeth, were founding members of the Black Sash movement, a protest movement of white women who stood silently in public places to protest against lost freedoms. John was imprisoned without trial for 93 days and after his release from prison the Brinks emigrated to Australia, travelling by ship.[6] They were greeted in Sydney by the Ovedoffs, who had also recently arrived in Australia. John acquired the Anchor Bookshop in Bridge Street, Sydney, which, while not being a profitable venture, for many years was a haven for anyone with an interest in race relations and politics, and Margaret, who had extensive teaching experience, was appointed to a lectureship at a Sydney teachers’ college.

Of these five South African emigres, only two, the Brinks, were to have a long-term involvement with SADAF. In mid-1963, soon after SADAF’s formation, the Ovedoffs left Sydney, when David Ovedoff, a physician, was appointed to a senior medical position in the United States, but both Rhona and David Ovedoff would retain an interest in SADAF’s work.

There were two other participants at the April 1963 meeting at the Ovedoffs’ residence who would have an important role in the formation of SADAF in Australia, Edward St John and Helen Palmer. St John was not only a leading barrister but also had political ambitions. He joined the Liberal Party in 1964 and was a member of the Balmoral branch within the Warringah federal electorate. He was elected to the NSW State Council executive and, early in 1966, he was a candidate for Liberal Party pre-selection in two federal electorates, Warringah and North Sydney. He was defeated by Warringah’s sitting member, JS Cockle, but Cockle died later in the year, before the general election. In North Sydney, he lost narrowly to Bruce Graham, former member for St George, and so he again contested the Liberal Party’s pre-selection for Warringah on 24 September 1966.

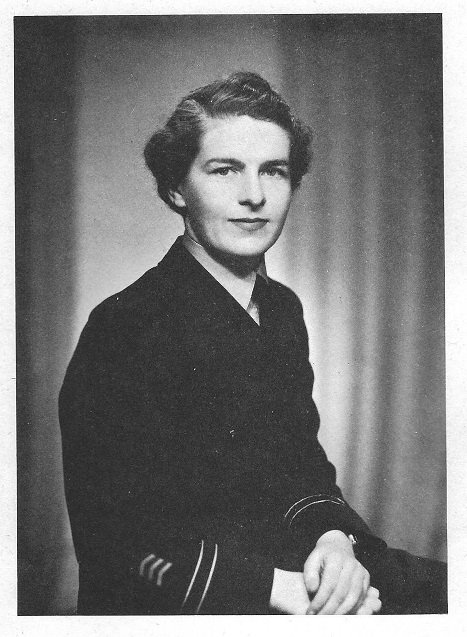

The other significant participant in the initial SADAF meeting was Helen Palmer, the daughter of Australian-born writers, Nettie and Vance Palmer. She was a teacher, writer and political activist and it was her energy and commitment that was instrumental in the formation of SADAF. In 1957, with the support of an editorial board, she had launched Outlook, an independent bi-monthly socialist journal and Outlook would regularly publish reports and commentary on the political situation in South Africa. Articles included ‘South Africa: explosion point’ (a commentary on the public outcry after the Sharpeville shootings, April 1960), ‘Why they leave South Africa’ (October 1961), and ‘Luthuli’ (reporting on the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Chief Albert Luthuli, December 1961). The Ovedoffs were the unnamed authors of the latter two articles.

Helen Palmer’s correspondence shows that in 1961 she had befriended the recently arrived Ovedoffs and encouraged them to write and provide information about the political situation in South Africa.[7] The Palmer papers include several letters (mainly Palmer’s) organising groups of people who would meet in private homes, sometimes Helen’s and sometimes the Ovedoffs’ residence.

The papers include a Helen Palmer invitation of 18 March 1962 to a meeting with Derick Marsh and David Ovedoff at Helen’s home in Sydney. Those invited included political associates such as Margaret Holmes, Maurice Isaacs, Harold Ford, Faith Bandler, and Walter Stone. The invitation read:

I know you will find what they have to say of absorbing interest. But we have a further aim: to consider how we can help develop in Australia some support for Africans in their struggle for independence and indeed for a tolerable life. One suggestion already made is the holding throughout Sydney of a chain of “cottage meetings” addressed by South Africans and the raising of funds for the “Defence and Aid” committee sponsored by Canon Collins …’[8].

Helen Palmer in WAAAF uniform during World War II (frontispiece to Helen Palmer’s Outlook/Helen Palmer Memorial Committee)

Helen Palmer in WAAAF uniform during World War II (frontispiece to Helen Palmer’s Outlook/Helen Palmer Memorial Committee)

It is not clear who decided to form an Australian branch of the Defence and Aid Fund, but there is no doubt that Helen Palmer’s editorship of Outlook and her initiative in either convening or encouraging ‘cottage meetings’ of politically committed individuals was a significant factor in the formation of SADAF.

SADAF’s papers do not include information on the convening of the initial meeting at the Ovedoffs’ residence in April 1963, nor are there detailed minutes of that meeting. The draft agenda for the meeting indicates, however, that the purpose of SADAF would be to provide relief for the oppressed, with the group having similar ideals to that of IDAF. The Fund would have no political associations and would seek to recruit prominent people from ‘a cross-section of society’ as supporters.[9] These early sponsors included clerics, authors and writers, academics, and politicians or political activists.

Helen Palmer was appointed liaison officer for the committee. In early July, she wrote to her friend Dr Robin (Bob) Gollan at ANU, reporting progress in organising SADAF’s founding public meeting.

I’m somewhat a poor relation on the committee, having been put there by our South African friends to see that the English Christian Action [i.e. IDAF] people get something done … and keep the feet on the ground; but as our secretary is on holiday and the president is in hospital, the committee (self-appointed) is a bit haywire. The Lord Mayor [Harry Jensen], who agreed to chair the meeting and give us the Lower Town Hall, decided at the last minute that he would rather we postponed it until after he had civically received footballers[10], trade missions from the cursed country; thank God, we said, stuff it, but be a patron and help us later.

Palmer indicated her pleasure that students in Canberra would be boycotting and protesting touring footballers. ‘Our South African friends say this is the tender spot in Verwoerd’s armour …’[11]

SADAF’s founding public meeting was held on 17 July 1963 at Stawell Hall, Macquarie Street, Sydney. Professor Julius Stone and Dr Derick Marsh, both from the University of Sydney, were speakers, with Edward St John as chairman. The resolution from the meeting determined ‘to launch the South Africa Defence & Aid Fund in Australia to assist in the defence of persons suffering under the … laws [of South Africa] and the support of their dependents, and to work towards the repeal of the …laws’. As well as the South African emigres, SADAF’s organising committee included the prominent Labor lawyer Maurice Isaacs and the publisher Kenneth Wilder.[12]

At this stage there was no membership of SADAF independent of the organising committee. Given St John’s prominence in Sydney’s legal circles, including his ICJ connection, he was very much the public face of the Fund, and it soon became apparent that he favoured a conservative apolitical model for SADAF, focussing on fund raising, public meetings and letter writing. He was certainly not attracted to activist politics, and he was opposed to Helen Palmer’s role within SADAF. Soon after the founding public meeting, acting with the support of a majority of the executive committee, he moved to have her removed from the committee; an action which would in turn lead to a damaging split in the organisation.

The minutes of SADAF’s executive committee of 1 November 1963 recorded ‘that the Chairman informed the meeting that with the approval of a majority of members of the committee he and Mrs Brink had seen Miss Palmer the previous night and requested her resignation from the committee, which she agreed to give’.[13] In the event, Helen Palmer did not agree to resign from the committee and, as a consequence, a special meeting of the executive committee was convened for 28 November with ten members in attendance. The eight-page minutes of the three-hour meeting were headed:

CONFIDENTIAL

The contents of these minutes are confidential and should not be disclosed to or discussed with any person who is not a member of the Defence and Aid Fund Executive Committee.

Edward St John as chairman of the meeting prosecuted the case for removal of Helen Palmer from the committee. He first stated that the committee was entitled to ask whether Miss Palmer was a communist and drew attention to the contents of the August 1963 issue of Outlook that featured an article ‘The split in the socialist world’. (The authors of the article were the American socialist economists Leo Huberman and Paul Sweezy.) St John argued that, considering this article, the committee was concerned to inquire whether, having left the Party, Miss Palmer had really ceased to be a communist in her thinking and actions. He also mentioned that Palmer remained friendly with many communists.

Verwoerd (South African History online)

Verwoerd (South African History online)

Given the length of the meeting, there was extensive debate, with Derick Marsh arguing that the political views of committee members should not be considered at all by the committee, since it was outside the scope of the committee. Others challenged this view and it was clear that St John would not have continued with SADAF if Helen Palmer was allowed to stay on the committee. The resolution to expel Palmer was passed by six votes to three (Derick Marsh having resigned from SADAF during the meeting, rather than participating in the final vote).

Rather incongruously, the minutes of the meeting concluded: ‘The Chairman said he hoped Miss Palmer would not feel he was being hypocritical if he expressed the committee’s gratitude to Miss Palmer and to Outlook for their help and support’. Hypocrisy or otherwise, the decision to expel Helen Palmer was a shock to many supporters of SADAF. There were resignations and the loss of the most active member of the committee reduced the Fund’s effectiveness.

Opponents of the removal saw it as an irrevocable blow to the organisation as a broadly based political and consciousness-raising body. Many trade unions were alienated, and several high-profile supporters withdrew their support. Apart from Derick Marsh, Maurice Isaacs resigned from the committee. In the aftermath Marsh sent a circular letter to the sponsors advising them of the expulsion and expressing his outrage. As a result, eight of the Fund’s thirty-two sponsors resigned. Marsh was to have no further connection with SADAF and soon after moved to Melbourne to take up a position as Foundation Professor of English at La Trobe University. He had a distinguished academic career in Australia and died in Melbourne in 2018 at the age of 90.

St John countered Marsh’s initiative with a circular letter to sponsors and included a copy of the August 1963 Outlook journal, more than thirty copies having been purchased from the magazine’s publisher. A few of the sponsors protested at St John’s action but opted to remain as a sponsor. One who protested but remained was Sir John Barry of the Victorian Supreme Court.[14] He wrote to Edward St John on 25 February 1964:

I do not doubt the good faith of the Committee, and that the majority acted honestly and with the best of intentions. However, I think the majority was wrong in its attitude and in its decision to expel Miss Palmer.

Conceding it was proper to give it, the undertaking could reasonably have meant only that no person who was a member of the Communist Party would be permitted to be a member of the Committee. I gather that it is accepted that Miss Palmer left the Communist Party in 1956, and is no longer a member, and the gravamen of the charge against her is that some articles in the August 1963 issue of Outlook, a journal she edits, indicates that she has “not really ceased to be a Communist in her thinking and actions”. This seems to me perilously close to the attitude Macaulay denounced in his essay on Hallam’s Constitutional History, in the passage:

“To punish a man because he has committed a crime, or he is believed, though unjustly, to have committed a crime, is not persecution. To punish a man because we infer because of the nature of some doctrine which he holds, or from the conduct of other persons who hold the same doctrines with him, that he will commit a crime is persecution, and is, in every case foolish and wicked.”

Barry supported the protest from Derick Marsh but indicated that he did not intend ‘to take any action to withdraw his sponsorship’. Crucially, it was agreed by the supporters of Helen Palmer that the expulsion of Palmer from SADAF would not be publicised, as there was no desire to impact the anti-apartheid cause. This silence on Helen Palmer’s expulsion continued until October 1966, when Palmer herself wrote about the expulsion in an issue of Outlook. She commented: ‘Mr. St John has the semantic and philosophical problem of reconciling the liberalism of anti-apartheid with the anti-communism of a Liberal’.[15]

From Edward St John’s perspective, probably the most damning and painful criticism of the Helen Palmer expulsion came from the former SADAF committee members, David and Rhona Ovedoff in America. On 13 November 1963, even before the expulsion meeting, they wrote a brutally frank letter to St John: ‘[W]e are writing [the letter] in considerable distress because we have just heard … that Helen Palmer has been asked to resign. In the first place, we feel responsible for having helped to persuade Helen to add the D and A fund to her already overcrowded schedule.’

Having described the proposed expulsion as a ‘form of McCarthyism’, the Ovedoffs continued: ‘[We] feel strongly that such activity is more suited to [South African Prime Minister] Verwoerd’s supporters than to his opponents’. St John responded, rejecting the ‘form of McCarthyism’ assessment, and other letters were exchanged, but there is a sense that the friendship between the two parties was now diminished and there is no evidence that the Ovedoffs had any further involvement with SADAF.[16]

Coinciding with the upheaval of SADAF’s committee a major trial was underway in South Africa. Known as ‘the Rivonia Trial’, it arose after, on 30 October 1963, ten defendants were charged with sabotage. On 12 June 1964, Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and six others were convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. The challenge for the Defence and Aid movement to provide defence support was considerable. On 17 February 1964, SADAF’s re-jigged committee organised a public meeting, held at Sydney’s lower Town Hall, addressed by the Lord Mayor Harry Jensen, with supporting speakers Edward St John, Rev. Alan Walker and Margaret Brink. On 23 April 1964, St John, together with Margaret Brink, addressed a civic meeting organised by the Lord Mayor in Newcastle.

Despite the increased awareness of the anti-apartheid struggle resulting from the outcome of the Rivonia Trial, SADAF struggled to raise money and, in the absence of political activism, the organisation’s principal focus became publicising the loss of human rights and civil liberties in South Africa and sponsoring speaking tours. SADAF’s on-going financial contribution to IDAF would remain modest, with the Fund rarely contributing more than $2000 each year. IDAF IDAF, however, developed into a huge enterprise, driven by a network of volunteers across the world.

In the words of Denis Herbstein: ‘The bare statistics of the defending and aiding account for the more visible aspect of IDAF’s contribution – tens of thousands of men and women offered the protection of lawyers, an incalculable number of prison family dependants on welfare, adding up to almost £100m orchestrated from London …’[17] The remarkable thing is that, on 18 March 1966, IDAF had been declared unlawful in South Africa by a proclamation under the country’s Suppression of Communism Act, so for many years the distribution of funds would be a closely guarded secret.

The year 1966 was to be eventful for both SADAF and Edward St John. In anticipation of a general election, St John contested the Liberal Party’s pre-selection for Warringah; he was successful and on 26 November 1966 was elected to Federal parliament. Also, for a brief period during the year he had served as an acting judge of the NSW Supreme Court. The Warringah pre-selection contest had been a bitterly contested campaign with extreme right-wing elements challenging Edward St John’s candidature.[18]

As for SADAF, in the second half of 1966, Robert Resha, Director of International Affairs of the African National Congress (ANC), was scheduled to undertake an extensive speaking tour in Australia, co-sponsored by SADAF and by the Melbourne-based group South Africa Protest. At a time in which Edward St John had been campaigning for Liberal Party pre-selection, his opponents within the Liberal Party had circulated a document claiming that SADAF was sponsoring a communist’s visit to Sydney.

St John was troubled that Resha’s reputation as a radical activist might through ‘guilt by association’ impact St John’s political campaign. As a result, the evening before Resha was scheduled to arrive in Australia, St John convened a meeting of members of SADAF’s committee at his chambers and they drafted a list of charges being made by Resha’s opponents.

The following day, when Resha arrived at Sydney’s Kingsford Smith Airport, he was greeted by St John and two other SADAF committee members. After clearing customs, Resha was taken to an airport coffee lounge where he was interrogated for thirty minutes by St John for evidence of any communist associations.[19] In retrospect, this action by St John and the SADAF committee members in questioning Resha was quite bizarre and potentially embarrassing for the anti-apartheid movement in Australia. The Resha tour had already been widely advertised and promoted, both by SADAF in Sydney and the South Africa Protest group in Melbourne, and Robert Resha was well-known internationally as a senior spokesman for the ANC.

In the event, Resha’s tour, the first involvement of SADAF with the liberation movement, was an outstanding success. He travelled to several states and gave numerous television interviews. An article in the Sydney-based Nation magazine records that St John’s obsession with the danger of communism intruded into his speech of introduction for Resha at a Sydney public meeting.

Mr Resha did not conceal his reaction. He said he regretted that the chairman had “found it fit and proper and perhaps expedient” to address him in that way. “We resent any suggestion from any quarter that we should be warned what to take care of, he said.” [20]

Nation had also reported on a meeting at the Mosman Town Hall that opened St John’s election campaign. The article noted that, at the meeting ‘it was no less doughty an anti-communist than Mr WC Wentworth who commended the candidate to the meeting. Those who stayed to the end of Mr St John’s prepared appeal for togetherness, heard no mention of South Africa or what it means not to work for a multi-racial society in Australia.’[21]

Wentworth in 1968 (Wikipedia)

Wentworth in 1968 (Wikipedia)

Edward St John’s choice in reaching out to WC (Bill) Wentworth to support his campaign was a strange decision. Wentworth had never displayed any interest or sympathy for victims of violence in South Africa. Some years earlier, in the week following the Sharpeville massacre, he had written in a letter to a Sydney newspaper:

Some of the people who are loudest in demanding the boycott of South African trade are the very same people who are demanding that we extend our trade with Red China. And yet, for every person who died in South Africa, many thousands have been butchered by the Communist Government of Red China.[22]

But St John went to extraordinary lengths to ingratiate himself with Wentworth. On 19 September 1966, and prior to the Warringah pre-selection, Wentworth, federal member for Mackellar, had written to St John indicating that Wentworth was satisfied with the strength of St John’s anti-communist credentials:

Thank you for letting me see your file regarding the elimination of Communist influence in the Australian fund for legal aid to South Africans. I have read it and it confirms the impression I previously held. You showed great courage standing up to Communist influences and to the accusations of “McCarthyism” which were levelled at you from the Left in consequence of your stand.[23]

The reason for Wentworth’s enthusiasm was that St John had lent a file of SADAF correspondence to Wentworth which mainly related to St John’s 1963 actions as president of SADAF in organising the expulsion of Helen Palmer from the Fund. After acquiring the file (on 14 September 1966) Wentworth had delivered it to the office of the Attorney-General in Canberra. Copies of the correspondence were then given to ASIO’s regional office in Canberra and the originals were returned to Wentworth on the following day. The material copied now comprises volume 3 of Helen Palmer’s personal ASIO file.[24]

Whether or not St John knew and approved of Wentworth’s action in copying the file and showing it to ASIO, at this time St John was still president of SADAF. His action without executive authority in sharing the Fund’s ‘in confidence’ correspondence with a third party indicates that, in order to enhance his political credentials, he was prepared to blacken Helen Palmer’s name by sharing confidential information with a conservative associate.

In the general election, Edward St John was elected member for Warringah, contributing to a landslide victory for the Liberal-Country Party coalition government, with a majority of 40 in a House of Representatives of 124 members. With 26 387 votes St John attracted 60 per cent of the first-preference votes in his seat.[25] In the light of his success, there is no doubt that he would have regarded his election as the first step in a significant political career. The Bulletin had already suggested that St John should be considered for immediate advancement to ministerial rank.[26]

Even before St John had taken his seat in Parliament, it seems that he was concerned about how he would be regarded by his Liberal Party colleagues in Canberra and whether his anti-apartheid connection would be regarded with suspicion. In order to address these concerns in December 1966 he contacted ASIO and was interviewed by ASIO’s Jack Behm, who later reported to Sir Charles Spry (Director-General of Security):

The reason why he sought contact with A.S.I.O. was because of his concern over the almost slanderous campaign waged against him by members of his own party during the elections. I told him we were horrified by the campaign and expressed sympathy to him. At the same time, I pointed out that while he has adopted a very anti-Communist attitude in the South African [sic: Africa] Defence and Aid Fund, such an organisation can be subject of Communist exploitation both internationally and nationally …[27]

Six months after St John’s election to Parliament, SADAF’s newsletter reported that he had resigned as President of the Fund, as he was seeking ‘to curtail a number of his activities’.[28] He was to have no further executive involvement with SADAF. Not only would St John have been bruised by the negative reaction to his attempts to limit the impact of Robert Resha’s speaking tour for SADAF, he also would have realised that a continuing involvement with an anti-apartheid organisation would not have enhanced his longer-term political prospects within the Liberal Party.

Gorton in 1967 (Wikipedia)

Gorton in 1967 (Wikipedia)

In the event, Edward St John was not warmly embraced by his parliamentary colleagues and his three-year term involved a succession of courageous but personally disastrous interventions. On 20 March 1969, the final straw was an attack on the personal conduct of Prime Minister John Gorton. St John contested the 1969 general election as an independent Liberal. He attracted 20.6 per cent of the formal votes and was defeated.[29]

Reflecting on the result on the Monday following the election, St John was reported as not being ‘disappointed in a personal sense’. He maintained that ‘we have achieved a great victory for what we believe is right’.[30] In spite of these comments, it is clear that Edward St John was ill-equipped for life as a Liberal Party parliamentarian. Significantly, after the formation of the Australian branch of the International Commission of Jurists in 1959, there had been no conservative Australian politicians willing to speak out about the racist violence of South Africa’s apartheid regime. When St John’s human rights and international legal principles threatened his prospects for personal political advancement, he had been prepared to limit the impact of SADAF and discredit a dedicated political activist.

After Edward St John’s resignation from an executive role with SADAF, the Fund focussed mainly on publicising South African politics and human rights issues and sponsoring speaking tours, and less on fund-raising. In 1970, the name of the organisation was changed to the Southern Africa Defence and Aid Fund in Australia, widening the Fund’s sphere of interest to include Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe) and other African territories south of the Zambezi.[31] Later again, the Fund became Community Aid Abroad (Southern Africa).

Following on from Robert Resha’s 1966 tour, a number of overseas speakers sponsored by SADAF, notably Judith Todd and Dennis Brutus, were to play a critical role in encouraging activism and shaping Australian attitudes towards racism in Southern Africa. Judith Todd undertook a lecture tour of both Australia and New Zealand in 1969, speaking out against the illegal regime of Ian Smith in Rhodesia. The South African-born teacher and poet Dennis Brutus toured in 1969 and 1970 and inspired Australians to boycott and campaign against sporting links with South African teams.[32]

For most of SADAF’s existence, John Brink was chairman and the backbone of the organisation. He lobbied politicians, wrote letters, and produced most of the Fund’s newsletters, and crucially was an encourager and inspiration for many activists. He died in Sydney in December 1997. Margaret Brink also continued to proselytise and speak in support of SADAF, and was an inspirational lecturer in English at Alexander Mackie Teachers’ College from 1961 to 1979. Years later she acknowledged that she had erred in supporting the expulsion of Helen Palmer from SADAF, but had felt at the time that her husband had wanted to have Edward St John as part of SADAF, and had felt that without St John the Fund would have been less effective.[33] Margaret died in 2008.

Helen Palmer died in 1979, shortly before her 62nd birthday. In the words of her friend Doreen Bridges, ‘she had already packed into her life about twice as much as most people achieve before reaching that age’.[34] Her journal Outlook, which had been regularly published since 1957, ceased publication in 1970. Palmer’s editorial commitment was just one aspect of a life committed to teaching, writing and extensive political activism. A commemorative volume with a selection of her writings and other biographical tributes was published by the Helen Palmer Memorial Committee in 1982.[35]

Edward St John died on 24 October 1994. He, along with Helen Palmer and the five South African emigres had been the key figures in the establishment of SADAF and he had used his influence and contacts in the law and other sections of the Australian community to bolster the Fund. Sadly, he manipulated the organisation in a way that limited its ability to provide genuine support for the victims of apartheid. In the end, no one could contest Justice Michael Kirby’s assertion that Edward St John was ‘a man of intriguing contradictions’.

Afterword

Two of SADAF’s founding South African emigres, Margaret Brink and Derick Marsh, published memoirs with reminiscences of political life in apartheid-era South Africa. In researching this paper both of these works have been valuable sources of information.[36] It is regrettable that in each case their story ended when they left South Africa and did not provide much information about their political campaigning in Australia. A number of others have been generous in their assistance: Jim Andrighetti, Ann Blake, Meredith Burgmann, Mark Finnane, Ian Hancock, Nicki Mackay-Sim (National Library of Australia), James Saville, and David Stephens.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He has produced Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references and including notes about the 1940 Canberra plane crash and the 1937 Stinson crash in Queensland, and has written a number of book reviews for us (use our Search engine), most recently of a biography of aviator, Charles Ulm. He has also explored the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

[1] Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, Abacus/Back Bay Books, Boston, 1995, p. 513.

2 Edward Roux, Time Longer than Rope: A History of the Black Man’s Struggle for Freedom in South Africa, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1964, p. 400.

3 St John’s expenses were paid by the International Defence and Aid Fund: Newsletter of the International Commission of Jurists, September 1959.

4 Denis Herbstein, White Lies: Canon Collins and the Secret War against Apartheid, HSRD Press, Melton Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2004, p. 30.

5 Derick Marsh, The Boy from Bloemfontein, unpublished memoirs, 1994.

6 Margaret Brink, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika: Memoirs of Apartheid, unpublished memoirs, 2004.

7 Helen Palmer to David Ovedoff, 20 October 1961: ‘We were delighted with your article on South Africa … As you know, there is a great deal of interest here in South African affairs, though it is not always well informed. Perhaps you could help us remedy that.’ Papers of Helen Palmer, National Library of Australia, NLA MS 6083 Box 8.

9 Southern African Defence and Aid Fund in Australia – records, 1961-1981, Mitchell Library, ML MSS 6630/1.

10 A touring South African rugby league team.

11 Helen Palmer to RA Gollan, 11 July 1963, Papers of Helen Palmer, National Library of Australia, NLA MS 6083 Box 8.

12 The Australian Defence and Aid Fund, Resolution, 1963 (author’s papers).

13 Minutes of SADAF Executive Committee, 1 November 1963.

14 Coincidentally, Sir John Barry was a close friend of Helen Palmer’s parents, Nettie and Vance Palmer.

15 Outlook, October 1966, p. 13; Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 1966.

16 The correspondence between Edward St John and the Ovedoffs is included in volume 3 of Helen Palmer’s ASIO file, National Archives of Australia, NAA A6119, 2920

17 Herbstein, op. cit, p. 328.

18 The 1966 Liberal Party pre-selection for the Federal seat of Warringah was profiled in R W Connell & Florence Gould, Politics of the Extreme Right: Warringah 1966, Sydney Studies in Politics, Sydney University Press, 1967.

19 Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 1966.

20 Nation, 26 November 1966, p. 5.

22 Sydney Morning Herald, 28 March 1960.

23 W C Wentworth to St John, Papers of Edward St John, National Library of Australia, NLA MS 7614, Box 1.

24 National Archives of Australia, NAA A6119, 2920.

25 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electoral_results_for_the_Division_of_Warringah .

26 ‘Mr Edward St John must go straight into the Ministry …’, The Bulletin, 3 December 1966, p. 13.

27 St John, Edward Henry miscellaneous papers, National Archives of Australia, NAA A6119, 3925.

28 SADAF Newsletter, July 1967.

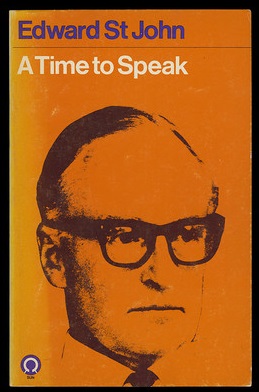

29 Edward St John wrote A Time to Speak, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1969, an account of his three years in politics from 1966 to 1969.

30 Sydney Morning Herald, 27 October 1969.

31 SADAF Newsletter, [August 1970].

32 Australian organisations campaigning against sporting links with South Africa included the Campaign against Racism in Sport (CARIS) and the more radical Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM).

33 Penny O’Donnell & Lynette Simons, Australians against Racism: Testimonies from the Anti-apartheid Movement in Australia, Pluto Press, Sydney, 1995, p. 112.

34 Doreen Bridges, ‘Helen Palmer: a personal memoir’, Overland, no.75, 1979, p. 17.

35 Doreen Bridges, ed., Helen Palmer’s Outlook, Helen Palmer Memorial Committee, Sydney, 1982. Palmer’s friend Rhona Ovedoff from the original SADAF committee was one of the contributors to this publication.

36 Margaret Brink, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika; Derick Marsh, The Boy from Bloemfontein.