Walter Phillips*

‘My late pilgrimage to Gallipoli’, Honest History, 21 March 2017

Since my childhood I have been aware of a connection with Gallipoli. This was largely because my father fought there and bore the marks of war in his wounded arm, although he got that later on the Western Front. I learned also that I was named after my mother’s eldest brother, who was killed at Gallipoli. I found out more recently that my father’s Welsh cousin had joined the Australian Light Horse and had died on a hospital ship and was buried at sea. Despite these connections, I did not have a strong desire to visit Gallipoli.

At school, at every anniversary of Anzac, we learned about the heroism of the Anzacs and of Simpson and his donkey. Each Anzac Day my father would take us to the service at the war memorial in Busselton, where we would see the veterans of Gallipoli marching with their medals on their chests. We wondered why our father would not wear his medals and march with the other men. He would show a little irritation if we got his medals out to look at them. He was a member of the RSL at some time; I saw his badge in a pigeon hole in his office, never worn. Some time after 1942, I noticed a large unopened carton in the bottom of his wardrobe. Being a nosy boy I opened it and found that it contained all the volumes of The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. I never asked about the books and they were never unpacked. All this made me think that my father had ambivalent feelings about the war and his part in it.

This history influenced my own attitude to the commemoration of Anzac in my adult years. I rarely attended Anzac Day services and I am uncomfortable with what has been called ‘the cult of the fallen soldier’. I have watched the Anzac Day march on television, especially when my uncle, the brother of the uncle killed at Gallipoli, was leading the 8th Division veterans. More recently, as a more meaningful remembrance of the fallen, my wife and I have attended the Dawn Service at the local military barracks.

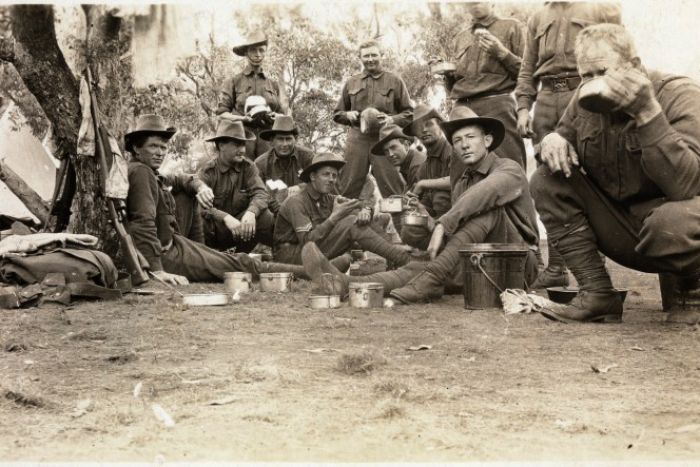

11th Battalion soldiers at lunch, Blackboy Hill, c. 1915 (ABC News/Battye Library)

11th Battalion soldiers at lunch, Blackboy Hill, c. 1915 (ABC News/Battye Library)

My father goes to war

I used to imagine that my father was among the Anzacs who struggled ashore in the darkness on 25 April. But when I was 15 my father told me that he was not in the first landing but in a later landing. I thought at first that this was something later in the day, but in time I realised that this was not so. On Anzac Day in 1992, I was in Perth staying with my brother John. It was the 75th anniversary of Anzac and in the morning I found John looking for our father in a double-page reproduction of the photograph of the 11th Battalion at the Great Pyramid in the West Australian. There was no one like him. We subsequently found out that he was not there, but we did not know why. This prompted me to look up my father’s military record in the National Archives.

My father was an English immigrant who arrived in Western Australia in January 1912, aged 19 and fresh from Harper Adams Agricultural College in Shropshire. In 1914, he was working on the State Farm at Brunswick Junction in the South-west. He did not rush to enlist at the declaration of war but, on the eve of his 22nd birthday he went to Bunbury, passed his medical on 24 September and was ready to enlist on 28 September 1914. He did not go to Blackboy Hill Camp until 15 October, and that is given in his record as his enlistment date.[1]

By the time my father arrived at Blackboy Hill the ‘original’ 11th Battalion was preparing to embark for overseas. The first reinforcements had already been sent to Melbourne to complete their training. After my father’s four months at Blackboy Hill he became part of a later reinforcement and embarked on the SS Itonus at Fremantle on 22 February 1915. He arrived at Port Suez late on 19 March and entrained for Cairo the next day. We know nothing of his time in camp in Egypt, but he left Egypt with the 11th Battalion reinforcements on Friday, 7 May, arriving at Gallipoli on Sunday, 9 May. He was there for the massive Turkish attack on the night of 19 May, when the Ottomans suffered huge casualties. According to the historian of the 11th Battalion it was ‘a veritable inferno’. But my father never told us anything about this experience, or of the remarkable truce to bury the dead a few days later.

By June the campaign had settled down to the stalemate of trench warfare, ‘sapping and sniping’ the order of the day. The Anzacs had to burrow forward rather than advance over open ground. Conditions became almost unbearable in July, with the heat and a plague of flies. The health of the troops was beginning to suffer, with many men going down with diarrhœa and dysentery. On 29 July my father was admitted to hospital with diarrhœa. He told me once that he was carried off Gallipoli with dysentery on a stretcher. I had thought that this had happened at the great evacuation in December, but it actually happened on 31 July when he embarked on the HMHS Neuralia and was admitted to hospital (at Heliopolis near Cairo) with dysenteric debility. He remained in various hospitals in Egypt until 20 November when he rejoined his unit at Sarpi Camp on Lemnos. (The 11th Battalion had left Gallipoli for Lemnos on 15 November, arriving at Mudros on 17 November.) He was admitted to hospital again on Lemnos with pyrexia (fever) on 4 December and rejoined his unit on Christmas Day.

In the New Year, the 11th Battalion sailed to Alexandria, arriving there on 7 January. They were sent straight to the Canal Zone, which they were to guard for some three months. My father told us a little of this time in Egypt. The incident I remember most clearly was about the attendance of the Prince of Wales at the Brigade church parade on Sunday, 19 March. After the service the Prince took the salute at the marchpast. As he was leaving, the Prince tripped over a form and fell flat on the sand. I found an account of the incident in the Battalion history, much as it was told to me.

Soon after this, my father sailed with his battalion from Alexandria to Marseilles to serve on the Western Front. He was promoted to corporal on 14 August 1916. He was recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal and awarded the Military Medal for his part in the action at Le Barque, near Bapaume, on 27 February 1917. He was an Acting-Sergeant briefly in 1917 and apparently intended to apply for a commission. However, he sustained a serious injury to his right arm at Passchendaele on 20 September 1917; this put him out of action for the remainder of the war. He spent the following 12 months under medical care in England and returned to Australia in November 1918 for medical discharge.

I was surprised to see that my father had given his intended place of residence on discharge as ‘Lone Pine Pingelly’ in Western Australia. What could Lone Pine have meant to him? He did not take part in the battle to take it during the August 1915 offensive. The 11th Battalion was engaged in action against the Turks on Lone Pine on 19 May. Could his association with Lone Pine arise from that experience? We shall never know. But I can guess why he planned to be somewhere near Pingelly. His favourite brother, Sid, was managing a business there. However, Sid left Pingelly in 1919, taking his family to New Zealand. My father then moved to Victoria where his brother Arthur was living.

Hill 60 and the Anzac cemetery, 1923 (AWM H18638/RW Murphy)

Hill 60 and the Anzac cemetery, 1923 (AWM H18638/RW Murphy)

My father had been an aspiring poet. He told me his mother read his poems, giving him constructive criticism. He had an epic poem, An English Vision of Empire, published by the Australasian Authors’ Agency in Melbourne in 1919.[2] I knew nothing of this poem until some years after his death. He had given a copy to Arthur and his wife Jean, who gave me their copy when I visited in 1954. I was naturally very pleased to receive it and have read it several times. How I wish that I could have discussed it with him. Its significance for me is that it was written just after the war and conveys something of my father’s view of the war and of his sense of history and his belief in Britain’s mission, something which I had never heard him express. One stanza may explain why he joined up:

To Britain’s scattered lands abroad

It was an inward call;

The surging blood – our binding cord

Compelled us to unsheathe the sword –

With her to stand or fall.

Other stanzas express a belief in the righteousness of the cause:

With gallant Allies at our side

We trod the champions’ route;

With a matchless navy we defied

The hovering dark on land and tide –

Till our pregnant force bore fruit:

A ransom bought with blood to spare

The whole of mankind’s race:

A task that bound in sacred air

The studded gems of Britain’s care –

Now crowned by God’s good grace.

The poem goes on to call Britons to awake to their mission.

Now tranquil lies each battle zone,

And snuffed each cannon flame;

All glory blasts and carnage flown;

Say this itself gives Peace its throne?

Then Peace has lost its name.

Not yet the pedestal is gained;

More struggles lie ahead;

Nor here shall manhood be arraigned

For aiding aims to be attained

To justify our Dead.

The poem ends with a prayer for divine guidance and help.

The sentiments of this poem seem at variance with what I had sensed of my father’s attitude to the war and his part in it. I suspect that subsequently he had become disillusioned. He not only had aspirations to write poetry; he told me once that after the war he had thought of journalism. How seriously he pursued that I do not know. He might have wondered if he could continue farming, given his physical disability. However, he took up a soldier settler block at Koo Wee Rup to grow potatoes. In 1924 phenomenal floods in the region ruined him financially. Not knowing what to do, he took up the offer of another brother in Western Australia to teach him the drapery trade, in which his father and two brothers were engaged. This brother believed drapery was ‘in our blood’. It was the end of my father’s youthful aspirations. He had also been disappointed in love while at Koo Wee Rup. His subsequent marriage ended unhappily.

Station Street, Koo Wee Rup, 1920s (Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp Historical Society)

Station Street, Koo Wee Rup, 1920s (Koo-Wee-Rup Swamp Historical Society)

My Uncle Walter

I had little interest in my uncle, Walter Hervey Thyer, in my youth, especially after the break-up of my parents’ marriage. We were estranged from our maternal relatives and my mother had taken her brother’s photo, which had hung in our lounge. In time, the breach was healed and I began to take an interest in my maternal family history and especially in my deceased uncle. Objects relating to him were passed on to me as his namesake, such as the medallion with the image of Simpson and his donkey, which the Commonwealth Government sent to the next of kin of those killed on Gallipoli. Later I received another handsome medallion bearing the image of Britannia and a lion, with the inscription, ‘He Died for Freedom and Honour’. This medallion was known as ‘The Dead Man’s Penny’, for it was sent to the families of all who lost their lives in the Great War, with the dead relative’s name inscribed on it. I had the medallion mounted in a circular frame and it now hangs in my study. I also received a transcript of the diary my uncle kept from the time of his embarkation to the eve of his death at Gallipoli.

Walter was the eldest of seven children who had lost both parents by the time Walter was fourteen, when the children came under the care of maiden aunts. Walter left school and obtained a junior position in the Perth branch of McLean Brothers and Rigg, hardware merchants. Conscientious and responsible – and religious – he had worked his way up in the firm to the position of accountant, which is what he gave as his occupation on enlistment on 19 November 1914, four months from his 25th birthday. He joined the 16th Battalion, and was promoted to corporal while in training at Blackboy Hill. He sailed for Egypt in February 1915 on the same ship as my father. They never met and I doubt that my father was aware of this coincidence.

Walter was in camp near Cairo for a month from his arrival on 20 March, during which time he served as Order Corporal. He was promoted to lance-sergeant on 9 April and put in charge of Battalion Baggage. On 23 April, his Battalion moved to Mustapha Pasha Barracks near Alexandria. Here he saw hospital ships bringing the wounded from Gallipoli, and sometimes Turkish prisoners of war arriving. On Sundays, when there was no church parade, and sometimes when there was, both in Cairo and Alexandria, Walter went to one of the Anglican or Presbyterian churches or the American Mission and occasionally to meetings of Christian Endeavour. He found the churches well-attended, on one occasion ‘absolutely full of soldiers’.

Walter was at the Mustapha Barracks for three months. They sailed for Gallipoli on 14 July and landed after midnight on 19 July with bullets flying overhead. He got into a dugout in Shrapnel Valley at 4 am. He was put in charge of Quartermaster Fatigue, drawing the battalion rations. There was frequent ‘standing to’ without much engagement. After a couple of days they were issued with gas masks and were inoculated for cholera. Walter enjoyed bathing in the sea after dark, even though the Turks were lobbing shells into the sea around them. One night, the sea was ‘highly charged with phosphorous’. On 2 August, Walter was promoted to full sergeant and the next day put in charge of a platoon, in place of a sergeant taken off to hospital.

Walter was in ‘Shrapnel Gully’, as he headed each entry in his diary, for 19 days, but from 7 August he headed each entry ‘on the war path’, as his Battalion took part in the August Offensive. They were part of Monash’s 4th Brigade, which attempted unsuccessfully to take Hill 971. For the first few days he struck an optimistic note in his diary, but he began to suffer from lack of sleep. Water was scarce and the stench of the dead was ‘rather awful’ and the flies ‘very bad’. Many men were going off sick. But on 14 August Walter was promoted to second lieutenant, so he fared ‘better under the care of a batman’.

On 22 August, when the bombardment started early he watched the slaughter from his outpost and wrote ‘God grant this business will soon be finished it is terrible’. On 27 August, he got a periscope shot in his face which affected his left eye. The next night he was on duty all night. He went to sleep walking and fell a few times. Both eyes were bloodshot and he got festers from the least scratch. This was his last entry in the diary. The following entry was made by another hand on 29 August:

Walter at his uncle’s grave (Timothy Phillips)

Statement by Serg Major Ozanne

Owing to the shelling of this position by the Turks it was almost impossible to move in daylight. Walter went down to get some fresh food from the stores … when suddenly a shell burst & poor Walter fell & died almost instantly not a word from him.

That same evening I laid him to rest in his blanket … Walter sleeps on the slope of a ridge I have called the “Ridge of Death” through so many of our lads losing their lives there.

A visit to Gallipoli

It would seem then that I had reason enough to visit Gallipoli. I did think about it as the significant anniversaries approached. In 1995, I noticed an advertisement from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs inviting direct descendants under 35 years of age of an Australian Anzac to apply to be part of the ‘Pilgrimage to Gallipoli to Commemorate the 80th Anniversary …’ I applied unsuccessfully on behalf of my son Peter, thinking I might accompany him as he had a disability. As the centenary of the landing approached it did occur to me that I might stand a good chance of selection as one of the few surviving sons of an Anzac, but I dismissed the thought. Being there on Anzac Day did not appeal to me, and I certainly could not go wearing my father’s medals since he himself would not wear them.

Why then did I make this pilgrimage at the age of 85? Sometime in 2013 I began to take a deeper interest in the Great War, largely at the prompting of my nephew who was living temporarily in France not far from the battlefields of the Western Front. He was interested in his grandfather’s war experience and I began to write something in response to his questions. My interest deepened with a visit to the Australian War Memorial in February 2015 to see the excellent Great War exhibition and in April 2015 my wife, myself and our son Timothy visited the Imperial War Museum’s World War I Centenary Exhibition at the Melbourne Museum. Over coffee afterwards, Timothy, who was impressed by the exhibition, said he thought it might be interesting to see Gallipoli. I told him I had sometimes thought of it, at which he suggested that we might go together during the school vacation in September 2016. So it was decided.

We engaged Kenan Çelik OAM, a Turkish authority on the Dardanelles campaign, to guide us. On 14 September, Kenan picked us up at our hotel in Eceabat (formerly Maidos) and took us first to the village of Bigalı (Boghali), where Mustapha Kemal had his headquarters. A number of Turkish flags were draped in the narrow street. There was also a stall of souvenirs. After coffee in the café we visited the adjacent square which was overlooked by a larger than life statue of Mustapha Kemal Atatürk. Around the walls were enlarged photographs, including the well-known photo of Esat Pasha and other officers sitting around ‘shattered long nosed cannons of the enemy’. Whether it was intended or not, all this impressed on us that Gallipoli was a Turkish victory.

From Bigalı we were taken to Hill 60 Cemetery. I had forgotten to look up the reference to my uncle’s grave but I strolled along the first row to the right and there I found it. I had not anticipated how much this would move me. Here was my tangible connection to Gallipoli.

After this we visited Anzac Cove and the beaches and then the sites of the various battles of the campaign and their cemeteries. We spent more time at Lone Pine with its substantial memorial. I was fascinated by a man wearing a slouch hat but otherwise in ordinary clothes, standing on the memorial; he appeared to be keeping vigil. I caught his eye briefly and gave him a little salute which he returned. He was still there when we left.

We saw little physical evidence of the battles. The terrain was rugged and daunting but covered with vegetation. Near Lone Pine we did see some trenches, rather shallow, but still hiding some evidence of war. Kenan found some shrapnel in a trench. Some trenches were covered with pine logs as the Turks had done. At the same place there were examples of the tunnelling used by the Anzacs in the campaign. The pine logs around the openings had obviously been renewed.

My overall impression on this first day was of great calm. My son found it eerie. Everything is neat and tidy. The cemeteries are all well-kept, a tribute to the men buried in them. Each cemetery has an altar-like structure at its centre with the inscription, ‘Their name liveth for evermore’. It is a transformation of the battlefields as they were found in 1919. There was some agreement that the remains of the fallen would be buried where they fell, but my uncle’s remains were exhumed from his grave in Norfolk Trench Cemetery and reinterred in Hill 60 in May 1921. The photograph of his grave in Hill 60 sent to his aunt by the Australian war graves service shows a plain white wooden cross and a stone in front on which his name and details are faintly inscribed. This was very different from the grave as I found it.

Alay (57th Regiment) cemetery (Timothy Phillips)

Alay (57th Regiment) cemetery (Timothy Phillips)

There were few visitors to the Anzac cemeteries and the folk we saw appeared to be visitors from abroad, like us. But we did see some Turkish visitors at the site near Lone Pine where we saw the trenches. The Turkish people had extra public holidays during the time we were visiting Gallipoli. We saw them in large numbers when we came to the Alay (57th Regiment) cemetery. This cemetery commemorates the huge number of the regiment lost at the beginning of the campaign. In one corner is a sculpture of the last surviving Turkish soldier of the Gallipoli campaign – he died in 1994 aged 110 – with his granddaughter. The Turkish visitors were keen to be photographed standing next to this sculpture.

Nearby we saw a relief representation of Atatürk sending the soldiers into battle, presumably commemorating that moment when he ordered them to die. At this site there is also a large statue of a Turkish soldier with rifle and fixed bayonet. There were several stalls selling souvenirs, including replicas of the Turkish soldiers’ caps. We saw boys happily running around wearing these caps. We had spent the day visiting cemeteries and memorials to those who surrendered their lives in a lost cause. But here were people rejoicing in a victory over an invading army. I recalled a verse from ‘Advance Australia Fair’ that we used to sing at school during World War II:

Should foreign foe e’er sight our coast,

Or dare a foot to land,

We’ll rouse to arms like sires of yore

To guard our native strand

I could not begrudge them their rejoicing.

When Australians or New Zealanders think of Gallipoli or the Dardanelles campaign we tend to think almost exclusively of the campaign in our own theatre of the war. I began to get a fuller picture of the campaign from recent reading and the point was forcibly made at the launch of Harvey Broadbent’s Defending Gallipoli at the Camberwell RSL Club in March 2015. As part of the introduction to the launch a member of the RSL produced a pie chart showing the proportions of the participants in the campaign. While I cannot remember the precise figures, the greatest section was Turkish, then British and French, while the Anzacs were not much more than a sliver.[3] Yet Australia and New Zealand are the nations that commemorate the event. Our commemoration is part celebration, inspired by Bean’s claim that ‘[i]n no unreal sense it was on the 25th of April, 1915, that the consciousness of Australian nationhood was born’.[4] That statement has morphed into the disputed claim that the nation was born at Gallipoli.

Cape Helles and beyond

On the second day of our visit we visited the Cape Helles region. On the way we stopped at the Rumeli Mecidiye Fort 13, one of the forts guarding the Dardanelles. It was fortified with large guns produced by Krupp. A sculpture celebrates Corporal Seyit who (it is said) could carry the 258kg shells to the gun.[5] The guns from the forts inflicted some damage on the Allied ships in their unsuccessful attempt to push through the Dardanelles on 18 March 1915, but it was the mines that sank two of the ships. Fort 13 also suffered some damage that day from the guns of the ships. There is a memorial nearby to 16 artillerymen who were killed that day.

Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial (gallipoli.gov.au)

Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial (gallipoli.gov.au)

Our next stop was the National Memorial Park at Morto Bay. The Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial is a huge grey structure looking out over the Bay to the Dardanelles in defiance, as it were, of those who tried to force their way through. There is also a memorial to the Unknown Soldier and a wall with a relief sculpture depicting the resistance of the Ottoman soldiers to the invading armies. This was a site which attracted many Turkish visitors.

The French cemetery of Seddul Bahr (Sedd el Bahr today, and there are other spellings) is not far from the National Memorial Park at Morto Bay, but is said to be infrequently visited. It is in fact a most impressive cemetery and quite different from the other cemeteries on the Peninsula. It is the consolidation of four French cemeteries created in 1915, one of them at Seddül Bahr. The present cemetery is actually in the Morto Bay area, significantly, close to where the French force landed (S Beach) on 27 April after their withdrawal from Kum Kale on the Asian side of the entrance to the Dardanelles. The cemetery holds the unidentified remains of some 12 000 soldiers in five ossuaries, the majority of the soldiers presumably from the French colonies, as colonial soldiers made up the greater part of the French Army of the Orient. There are also 2340 identified soldiers in graves in the cemetery.

The French graves have metal crosses or a Star of David for the grave of a Jewish soldier. The cemetery is a memorial to the French forces at Cape Helles. It was inaugurated on 9 June 1930 by General Henri Gouraud, who had commanded the Army of the Orient at Gallipoli. He was possibly influenced by the completion in 1924 of the Commonwealth Memorial commemorating all soldiers of the British Empire who served in the Gallipoli campaign.

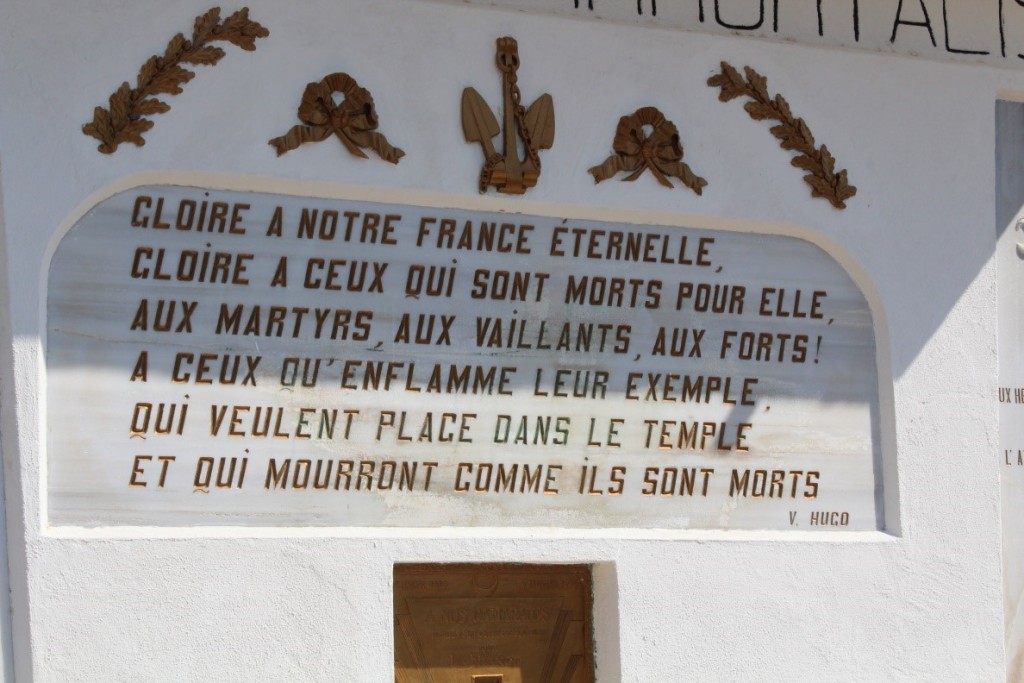

French memorial (Timothy Phillips)

French memorial (Timothy Phillips)

Another memorial to the Army of Orient was unveiled in 1927 on the Corniche in Marseilles, from which port they had departed in April 1915. But there was no Cape Helles memorial to the French until the creation of this cemetery. The tall obelisk bears the vertical inscription ‘La France et ses enfants 1915’ (‘France and her children’), and beneath are the Latin inscription ‘Ave Galle immortalis’ (‘Hail immortal France’), and a quote from Victor Hugo commencing (in translation): ‘Glory to our eternal France and to those who died for her’.[6] Various panels on the wide base commemorate the participants in the campaign, one honouring the anonymous heroes, colonial soldiers who died for France.

One panel on the Seddul Bahr memorial is a tribute from the Army of the Orient to their general, translated as, ‘It was here that the heroic General Gouraud was wounded in 1915 (he lost an arm)’. There is no mention on the memorial of the partnership with the British forces, but the story of the campaign on Cape Helles is told on a notice board at the entrance to the cemetery, in French and Turkish. It makes clear that the naval assault was carried out by ‘franco-anglais’ navies and the attack on Krithia was a ‘franco-brittanique’ exercise. Visiting this cemetery was a moving experience.

After seeing some of the smaller cemeteries in the region (Skew Bridge and Redoubt), we arrived at Seddul Bahr, the site of the fort or castle at the entrance to the Dardanelles. Built in 1659, it was armed with Krupp guns and garrisoned by Ottoman and German soldiers when the Royal Navy made its preliminary assault on the Dardanelles on 3 November 1914. The British shelled the fort, killing 86 Turks and some Germans as well. There is a memorial in the village of Seddul Bahr to the Turks who were killed, but not, as far as I know, to the Germans.

Seddul Bahr is also the site of V Beach, where the British attempted to land on 25 April 1915. Some 2000 troops were concealed in the River Clyde, a ‘Trojan Horse’ which was grounded close to the beach, but not as close as intended. Heavy naval bombardment of the Fort area preceded the landing but, in the lull between the bombardment and the landing, the Turks rallied and enfiladed the British troops as they emerged from the ship. Some who attempted the swim drowned with the weight of their packs. An airman reported that the sea around the area was red with blood. It was a day of horrors. Half the troops on the River Clyde had to wait until darkness to land.

French memorial, detail (Timothy Phillips)

French memorial, detail (Timothy Phillips)

On the day we saw V Beach, holiday makers were relaxing there and some were bathing where the River Clyde had sat. Some boys found the cemetery nearby a convenient place to hide. They disappeared when we came through the gate of the cemetery. There seemed to be an indifference to the significance of the site. In the same region there is an impressive memorial to men of the Ottoman 26th Regiment who resisted the British landing at V Beach on 25 April.

We also walked on W Beach, known as the Lancashire Landing after the Lancashire Fusiliers who landed there. Rusting remnants from the operations there are still visible. This was another place where many were lost in the attempt to land. Those who survived the firing from the Turkish defence had to cut their way through barbed wire entanglements on the beach. W Beach became the main centre of British operations at Cape Helles. The Lancashire Landing Cemetery above the beach also became the main cemetery for the fallen during the campaign at Cape Helles. It contains the graves of ‘over 1200’ soldiers from the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland and India, and some unidentified. There also graves of 17 men of the Greek Labour Corps, locals who were enlisted to unload ships and for constructing harbour works.[7] An inscription on the wall outside the cemetery states: ‘The 29th Division landed along this coast on the morning of April 25th 1915’.

We encountered few visitors at the memorial sites on Cape Helles, but there were more at the Commonwealth Memorial near Seddul Bahr. This tall obelisk is visible for miles around and from the sea. Unveiled in 1924, the Commonwealth Memorial is both a ‘battle memorial’ for the whole Gallipoli campaign and a place of commemoration for 20 885 servicemen of the Commonwealth (Empire) who died there and have no known grave. One panel at the base of the obelisk commemorates the Anzacs and the Indian Infantry Brigade. A multitude of names are inscribed on the inside walls enclosing the memorial, including those who were buried at sea in ‘Gallipoli waters’. It seems so comprehensive, but it gives the impression that the Gallipoli campaign was solely a British enterprise. While, admittedly, it was a British initiative under British leadership throughout, it was left to the French to put the record straight.

Final thoughts

Over these two days, with our expert guide Kenan Çelik, we saw most of the sites associated with the Dardanelles campaign, including Turkish memorials, and tried to imagine what it would have been like for those who took part in the conflict. But nature has covered the battle-scarred land and a peaceful atmosphere has descended on the peninsula. The memorials and cemeteries, however, tell of the huge sacrifice of life in the conflict, on both sides. I was impressed by the pride of the Turks as they visited their cemeteries and the great Martyrs Memorial. They were celebrating those who lost their lives in defence of their country, and their victory over the invaders. Kenan ventured the opinion that without the Germans the Turks would probably have been defeated, yet I did not see any recognition of the German participation in the campaign.

What is our remembrance of the Anzacs – and of the others in the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, whom we mostly forget? What were the many who lost their lives fighting for? The French memorial praises those who died for France. The medallion commemorating my uncle says ‘He died for Freedom and Honour’. I puzzle over this, especially regarding those who died at Gallipoli. I suppose every soldier who dies in war dies for his country, irrespective of his country’s cause. But do we sometimes make heroes of those who have paid with their lives for our folly? The inscription on my uncle’s headstone states: ‘He did his duty’. Of that, at least, there can be no doubt.

Commonwealth memorial (Timothy Phillips)

Commonwealth memorial (Timothy Phillips)

I am glad to have been to Gallipoli, even at this late stage of my life. But apart from finding my uncle’s grave, I did not feel any great emotional response to being there. I guess my engagement was more intellectual. I had read much about the campaign and I wanted to get the whole picture, and to a large extent I think I did. Has the experience made any difference to my ambivalence about Anzac Day? I am not sure that it has. I do think we should continue to commemorate those who lost their lives in this campaign. But I don’t think the loss and the campaign should be glorified with the claim that Australian national consciousness was born at Gallipoli.

* Walter Phillips is an Emeritus Scholar at La Trobe University, Melbourne, and a former Reader in History there.

Notes

[1] His record states that he enlisted on 15 October, aged 21 years 11 months. He was born 9 October 1892, but he had not turned 22 when he signed to enlist at Bunbury.

[2] Frederick Wynne Phillips, An English Vision of Empire, Australasian Authors’ Agency, Melbourne, 1919.

[3] Australians and New Zealanders at Gallipoli were about 8 per cent of the total numbers from both sides. (Editor)

[4] CEW Bean, The Story of Anzac from 4 May, 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula: The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, vol. II, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1981 (first published 1941), p. 910.

[5] The reputed feat of Corporal Seyit or Seyid is considered here in Turkish, here in English translation and here in commentary. (Editor)

[6] The complete French text of the Hugo quote is in the illustration.

[7] Bean, Story of Anzac, vol. II, pp. 264-65.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.