John A. Moses*

‘The management of history in totalitarian countries: a cautionary tale’, Honest History, 4 December 2018

We welcome Professor Moses’ contribution to a well-traversed field. For related material, see: Margaret MacMillan on history teaching in China, Canada, Russia, Turkey, and the United States; material on the secondary history curriculum in Australia (use our Search engine with the term ‘curriculum’); Ayhan Aktar on Turkey; the introduction of ‘Western civilisation’ courses in Australian universities (use our Search engine again); and a very recent New York Review of Books article on the history curriculum in Indian schools. HH

It is a common place that the history instruction to which one was exposed at school and university was ‘statist’ and intended to inculcate into students the political values of the ruling classes. That, of course, sounds very Marxist but, to be honest looking back, that is what children at school and students at university were exposed to, at least in the education systems of the various Australian states.

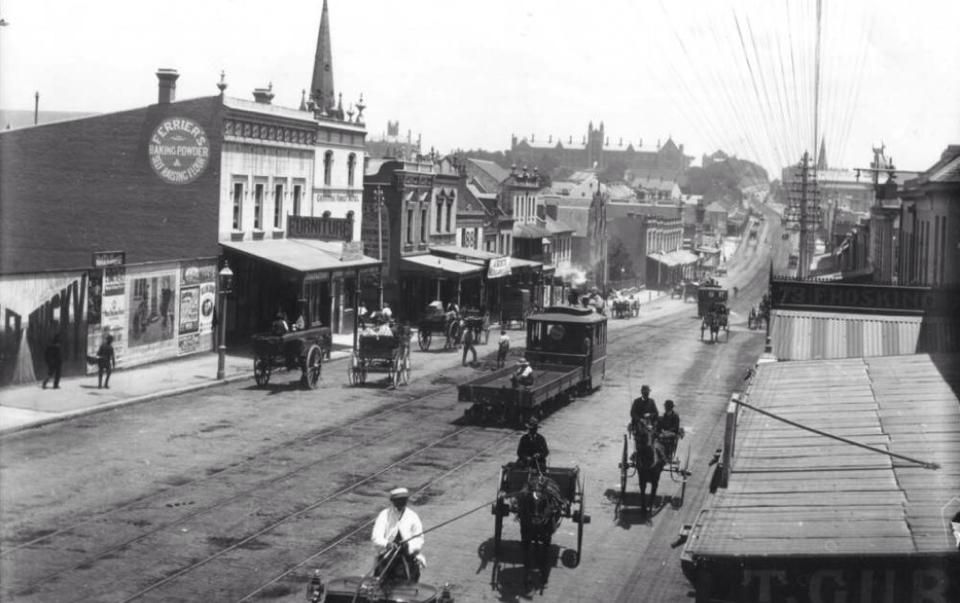

Broadway, looking towards the University of Sydney, c. 1890 (Pinterest)

Broadway, looking towards the University of Sydney, c. 1890 (Pinterest)

If one asks who was responsible for this phenomenon, then one would have to reply: the professors of history at the emerging state universities. They were all, to a man, willing supporters of Australian membership in the British Empire and Commonwealth. Take, for example, George Arnold Wood (1865-1928), the very first designated professor of history at Sydney, who, as a very young man, was appointed in 1890 to the Challis chair which he occupied until his death. In his self-perception, Wood was a ‘Whig’ historian who had a particular vision for the role of the British Empire in history as the bringer of justice and freedom to all who lived under the shadow of the Union Jack, on which at that time the sun never set. When the leaders of Empire deviated from this task, as in the Boer War, Professor Wood protested vigorously, suffering considerable contumely from his peers. But, when Germany invaded Belgium, Wood became likewise a vigorous critic of German imperialism.[1]

The same was true of the more recently appointed Professor of History at the University of Melbourne, Ernest Scott (1867-1939), who directed history instruction in Victoria from 1909 until his retirement in 1938.[2] The point is, however, that these men believed they were independent of any government control, though, of course, in Marxist terms they were really ‘bourgeois lackeys of the ruling class’. But they, on the contrary, believed very sincerely that they were entirely free to research and teach history as they saw it, without fear or favour. They knew, indeed, that they were political-ideological pedagogues but they certainly did not perceive themselves as beholden to any political masters. This was true of all their successors at Sydney and Melbourne, as well as the history professors in the younger state universities. (These academics were mostly former students of either Wood or Scott.)

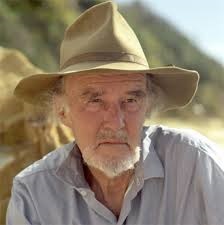

Manning Clark (ANU)

Manning Clark (ANU)

In the self-perception of each professor was the belief that they were responsible for the political and pedagogic formation of their students. Not surprisingly, though, there developed historians such as Manning Clark. Clark struck out on his own to promote an Australian nationalist historiography; a very anti-British thrust was the essence of his political-pedagogic endeavour. One might say that, with the advent of Clark, Australian historiography became inevitably more and more pluralistic, as befits any democratic society.[3]

In totalitarian societies of the recent past, namely in Nazi Germany and in the Soviet bloc countries, the respective regimes were very concerned to employ history as a means of political indoctrination and social control. In Nazi Germany, for example, it was crucially important for the regime to ensure that the Volk – in short, the nation – shared the same nationalistic and anti-Semitic values. People had to demonstrate the right Gesinnung – that is, mentality or attitude to life – in order to become truly National Socialist burghers, and to submit not just willingly but enthusiastically to the dictates of the Führer. To be genuinely German, one had to align oneself completely behind the will of Adolf Hitler. The medium of history instruction lent itself readily to this objective and there was no shortage of teachers and professors who willingly assisted in this project.

In Soviet-dominated countries, on the other hand, it was crucial for the regime to control what and how all subjects were taught in schools and universities, but, above all, it was history that was blatantly re-functioned to become the means of ideological formation for all subjects. Its pedagogic objective, derived from Marxism-Leninism, was to illustrate how the revolutionary party of the proletariat came eventually to power. The aim of this pedagogy was to produce a ‘new species being,’ that is, the genuine developed Soviet citizen. So, in both fascism and Soviet communism, the history profession became recruited into the front ranks of government-directed ‘thought police’.

The management of history in Nazi Germany

When the Nazis seized power in January 1933, the only academics who were alarmed were the few Social Democrats and critical Liberals. Those who were of Jewish descent or married to Jewish partners also took the cue to emigrate as soon as they could. The overwhelming majority of the bourgeois historians, however, either welcomed the Nazi ‘New Order’ enthusiastically or maintained a discreet silence, entering into what was called the ‘inner emigration’. What is significant is that the enthusiasts did not have to join the Nazi party; most of them agreed with Hitler’s analysis of contemporary history in any case.[4]

As patriots, these historians uniformly rejected the so-called diktat of Versailles – the World War I settlement – and polemicised against it and were, as well, almost all uniformly anti-Semitic. In addition, they were certainly all anti-socialist and had no problem with the fact that the democratic Weimar Constitution had been junked. From the moment of Hitler’s seizure of power, government was based on the Führer principle. These historians’ main concern was to regain Germany’s rightful place in the world, as they saw it; Adolf Hitler had succeeded in persuading most of them that he was the only German statesman capable of achieving that objective.

Meinecke (britannica.com)

Meinecke (britannica.com)

An outstanding professorial example was Professor Friedrich Meinecke (1862-1954), who was the long-time editor (1896-1935) of the prestigious historical journal, Die Historische Zeitschrift, the world’s very first such publication.[5] Meinecke had been a National Liberal monarchist prior to 1919, but accepted the transition to the republic, calling himself a Vernunftrepublikaner, meaning that he supported the new constitution and wanted to make it work, though at heart he was still a monarchist.

From 1933 onwards, Meinecke distrusted the Hitler movement, and with good reason. No sooner had Hitler seized power a new controlling agency had been set up entitled Das Reichsinsitut für die Geschichte des neuen Deutschlands (The Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany). The purpose of this agency was to control the ideological content of history publications and curricula content. A disgruntled Nazi student, by name Walter Frank (1905-1945), had persuaded the Nazi minister for culture and education (Kultusminister), Alfred Rosenberg (1893-1946), that he (Frank) could reliably lead such an institute, and so he was duly appointed.

Right from the outset, Frank had a problem with Meinecke and engineered his dismissal as editor of the Historische Zeitschrift. So Meinecke was replaced by the enthusiastic pro-Nazi Professor Karl Alexander Müller (1882-1964). Müller was remarkable because he had been the very first German Rhodes Scholar and became, in spite of his exposure to the liberal atmosphere of Oxford, one of the intellectual and spiritual precursors of National Socialism, being already virulently anti-Semitic. Indeed, Walter Frank had been one of Müller’s students in Munich; so Müller’s appointment to the editorship of the world’s premier historical journal was an example of inverse nepotism.[6]

The Nazis had wanted to replace what they called bourgeois historiography with folkish- (völkisch) inspired historiography. This prioritised ‘blood and soil’ (Blut und Boden) themes to explain the superiority of the Teutonic race and its heroes over especially the neighbouring Slavic and Romance peoples. Jews, of course, were categorised as vermin that infected the body politic. Since the uniqueness of a people lay in the purity of their blood, it followed that German cultural achievements outshone all others.

Müller (Wikipedia)

Müller (Wikipedia)

This kind of circular logic was characteristic of so-called ‘blood and soil’ thinking. And it was precisely this that Walter Frank’s institute for the history of the new Germany was set up to foster. In the Nazi program for creating a community of rabidly enthusiastic, racially- oriented patriots, the ‘right’ historical instruction was absolutely essential. The curious thing is that the most penetrating intellects among German professors at that time acquiesced in this ultimate absurdity. A template prepared by Nazi ideologues had been imposed on the mind of all historians so that all their output conformed to the party objectives.[7] It is sobering to ponder whether such a thing would ever be possible in Australia. Comfort may be taken in the quintessentially Australian characteristic of wanting to ‘keep the bastards honest’.

In my years as a post-graduate student in Germany (1961-65) I spoke frequently with my peers about this problem of the history discipline in Germany. The young Germans invariably said that, despite the ubiquitous presence of ‘Big Brother’, some scholars managed to do pioneering research of enduring value. In short, there were some ‘honest’ historians who managed to get their work published, provided that in their introductions they made the obligatory genuflection to Nazi ideology.[8] All works would be cleared for ideological conformity.

Despite all that, my German interlocutors conceded that a democratic open society was infinitely preferable. Eventually, those students had come to see that the Nazi goal of creating a new race of super men and women was Hirngespinst, that is, a chimera or just plain addle-brained.

The East German communist utilisation of history

Turning now from the ‘brown’ (Nazi) dictatorship to the ‘red’ in the (East) German Democratic Republic, we are confronted with a not dissimilar situation. At first, however, after the liberation of Germany from the fascist yoke, the historians in East Germany were eager to attend the resumed all-German national historians’ congresses. That is to say, historians of pronounced Marxist-Leninist conviction had intended to mix it, shoulder to shoulder, with the ‘bourgeois’ historians of the West.

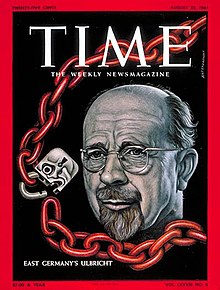

Ulbricht, Time Magazine, 25 August 1961 (Wikipedia)

Ulbricht, Time Magazine, 25 August 1961 (Wikipedia)

This intention, however, was soon abandoned and the East Germans withdrew behind their iron curtain and in 1953 set up their own journal, Die Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft.[9] That this publication was to conform strictly to the objectives of the Socialist Unity Party, the communist party of East Germany, was made clear to all historians by the party secretary Walter Ulbricht (1893-1973) in a paper published in the first issue in 1953 and entitled Brief an die Forschungsgemeinschaft der Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung (A letter to the research community for the History of the German labour movement).

The state’s intention was to bring out a multi-volume history of the labour movement; this history eventually appeared in 1968. Ulbricht had no reservations about instructing the historians how they should go about their work and what the result of their research should deliver. The objective was to demonstrate how the revolutionary movement of the working class eventually wrested power, with the intention of producing the Marxist-Leninist ‘new species being’. Indeed, Herr Comrade Ulbricht admonished the historians always to be aware that the prosecution of their discipline was for the purpose of showing how the laws of history unfolded over time to enable the realisation of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. Certainly, a historian who did not submit his or her mind to this proposition was ostracised.[10]

This was, indeed, how historical research was to be carried out, namely for the sole reason of showing how the revolutionary party of the proletariat finally came to power to usher in a golden new age of world history. To further this aim, university students in all faculties were issued on enrolment with a handbook of German labour history prepared under the direction of the notable Marxist-Leninist historian Jürgen Kuczynski (1904-97).

Kuczynski (Geni.com)

Kuczynski’s handbook was published like a Bible or prayer book, with a red ribbon to mark the pages one had reached. The volume was designed to look like a religious book, and its content certainly had the character of a catechism. For example, the heading on the opening page of text is inscribed, Die Lehre des Marxismus-Leninismus ist allmächtig, weil sie wahr ist! (The doctrine of Marxism-Leninism is almighty because it is true!). A better example of circular logic or special pleading is scarcely imaginable.

The point is that students in East Germany were virtually dragooned into becoming disciples of Marxism-Leninism. The parallel to the kind of indoctrination that was once practised in the Roman Catholic Church is overwhelmingly obvious.[11] So, the lesson to be drawn is that true freedom has to allow open expression of opinion without fear or favour from everyone and anyone who wishes to stand up or go into print to express their views. In short, a democratic society must cultivate what the German sociologist Jürgen Habermas designated as ‘the ideal speech situation’.[12]

By that, Habermas meant that an ideal speech situation was found when communication between individuals was governed by basic implied rules that allow participants to evaluate each other’s assertions solely on the basis of reason and evidence in an atmosphere free of any non-rational ‘coercive’ influences, whether physical or psychological. As well, all participants would be motivated solely by the desire to obtain a rational consensus. This reads as though it may well be concomitant with the objectives of Honest History.

* John A. Moses is a Professorial Associate of St Mark’s National Theological Centre, Charles Sturt University, Canberra, and is joint author with George A. Davis of a book on Canon David Garland and the origins of Anzac Day (Canberra: Barton Books 2013). A related article of his discusses the fallacy of Presentism in Australian history. See also his forthcoming work (with Peter Overlack), First Know Your Enemy: Comprehending Imperial German War Aims in the Pacific and De-Ciphering the Enigma of Kultur (Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publications, 2019).

US school children giving the ‘Bellamy Salute’ c. 1930s (thoughtco.com)

US school children giving the ‘Bellamy Salute’ c. 1930s (thoughtco.com)

German school children late 1930s (Wiener Library)

German school children late 1930s (Wiener Library)

[1] See John A. Moses, Prussian-German Militarism, 1914-1918 in Australian Perspective: the Thought of George Arnold Wood (Bern: Peter Lang, 1991).

[2] Stuart Macintyre, A History for a Nation: Ernest Scott and the Making of Australian History, (Melbourne University Press, 1994)

[3] Mark McKenna, An Eye for Eternity: the Life of Manning Clark (Carlton, Vic.: Miegunyah Press, 2011).

[4] Hitler’s views were certainly well known through the publication of his autobiography, Mein Kampf. See Eberhard Jäckel, Hitler’s Weltanschauung: a Blueprint for Power (Middletown Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1972).

[5] The founder of the Historische Zeitschrift was Heinrich von Sybel, who was von Ranke’s most famous student. In 1859, von Sybel founded the HZ, inspiring the French in 1876 to establish the Revue Historique. The English, under the half-German Lord Acton, founded the English Historical Review in 1886 and the American Historical Review began in 1895. Von Sybel had died that year and the editorship of the HZ was subsequently assumed by Friedrich Meinecke in 1896. He held the post until he was forced into retirement in 1935 by the Nazi regime.

[6] Recounted in detail by Helmut Heiber, Walter Frank und sein Reichsinstitut für die Geschichte des neuen Deutschlands (Stuttgart: DVA, 1966).

[7] See the pioneering work of Georg G. Iggers, The German Conception of History: the Nationalist Tradition in German Historiography from Herder to the Present (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1968).

[8] A classic example of this is the study by a Nazi post-doctoral student of Australia, Karl Heinz Pfeffer (1906-71), who came to Melbourne to work under the supervision of Professor William Macmahon Ball. Pfeffer produced an excellent study of Australian society at that time, entitled Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft in Australien (Berlin, 1936), except the preface teems with the then obligatory meaningless Nazi jargon.

[9] I would render the title literally as ‘The Journal for Historical Science’ since, as the historians to a man had to be party-aligned, they subscribed to the notion that Marxism-Leninism was ‘scientific’.

[10] Interview and correspondence with Dr Horst Drechsler, who lived in East Berlin and researched from the German colonial office files the history of their genocidal administration of South West Africa. Drechsler would not join the party, and so was marginalised among historians in the German Democratic Republic, though his work on German imperialism and racism was published because it conformed closely to the party line on the brutality of imperialism. See his Let Us Die Fighting: the Struggle of the Herero and Nama against German Imperialism (1884-1915) (London: Zed Press, 1980; first published 1966).

[11] On this subject, see Paul Collins, From Inquisition to Freedom: Seven Prominent Catholics and their Struggle with the Vatican (Sydney: Simon & Schuster Australia, 2001).

[12] See Jürgen Habermas, Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990).