‘First Things First and finding a way through’, Honest History, 12 June 2018

Mark McKenna reviews Griffith Review 60: First Things First

As editor Julianne Schultz explains in her introduction, ‘First Things First’ – a title suggested by Melissa Lucashenko – is the first issue in Griffith Review’s 15-year history to carry an explicitly Indigenous theme. When the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’ was delivered to the people and parliament of Australia in May 2017, Schultz felt that ‘something had shifted’. After so many broken promises and false starts, the momentum finally seemed to be moving in favour of substantive political change for Indigenous Australians. There was a sense of ‘renewed promise’ and, as Megan Davis notes in this volume, an understanding that the extensive deliberative process that led to Uluru was an ‘Aboriginal innovation’ – a real ‘game changer’.

Then came the ‘shock and heartbreak’ of the Turnbull government’s rejection of the Voice to Parliament, one of the key recommendations of the Uluru Statement and the Referendum Council’s report. Promise quickly turned to anger and dismay. It seemed impossible to imagine that such a carefully negotiated, beautifully crafted and powerful document could end in summary dismissal.

Then came the ‘shock and heartbreak’ of the Turnbull government’s rejection of the Voice to Parliament, one of the key recommendations of the Uluru Statement and the Referendum Council’s report. Promise quickly turned to anger and dismay. It seemed impossible to imagine that such a carefully negotiated, beautifully crafted and powerful document could end in summary dismissal.

This outstanding collection of essays, reportage, memoir, poetry and fiction represents an urgent call to action and adds substantially to a rising tide of voices calling on the federal government to reconsider its rejection of the Uluru Statement. Contributors explore the significance of Uluru from every possible angle: politics, health, education, prisons, media and communication, science, research, the role of women, history, and the future.

The unique contribution of ‘First Things First’ is the breadth and diversity of its vision; we can appreciate the issue from multiple standpoints simultaneously. From Megan Davis we get the pre-history and fine detail on the Uluru Convention, from Pat Dodson an assessment of the future political and legislative challenges regarding Recognition. Kathy Marks explores the struggle for treaties in Victoria and other states. We hear Marcia Langton’s call to authorities and Aboriginal men to address the violence and abuse committed against Indigenous women and children.

Taken as one, the contributions to GR 60 map the intricate web of Indigenous aspirations and policy challenges in the full context of Australia’s history and contemporary politics. After all, the ‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’ – if we can summon the will and concentration to truly embrace it – potentially touches every aspect of life in this country. Reading this collection from start to finish has the same effect as sitting in an auditorium and listening to one speaker after another come to the podium. The voices interweave, cross-reference and eventually cohere. In the end, they seem to be speaking in unison.

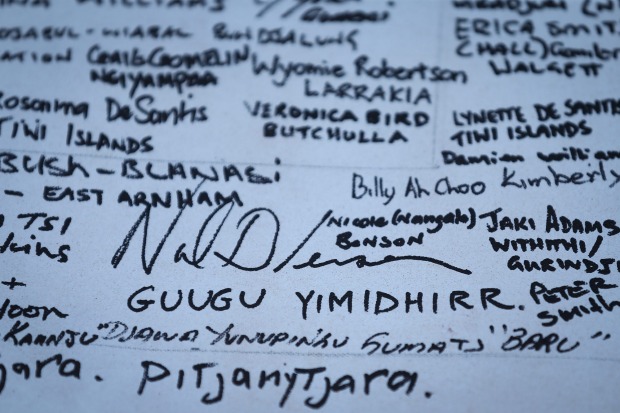

My already dog-eared copy of the volume is marked with underlined passages and marginal comments – too many to do justice to all contributors here. Alex Ellinghausen, the photographer who travelled to Uluru with the late Fairfax journalist Michael Gordon, documents the 2017 Uluru Convention in his ‘photo essay’. One of the most memorable images is Ellinghausen’s close-up of delegates’ record of attendance, each name and signature accompanied by the attendee’s Country of origin. The photograph captures the diversity of Australia’s ‘First Nations’ people at the same time as it reflects Pat Dodson’s description of Uluru for Indigenous Australians today: ‘the spiritual centre of many traditions that cross the country’.

One of the strongest shared convictions among the contributors is the role that history has played in shaping the reality of Indigenous Australians’ lives today and their demands for social and political justice. The present past. I lost count of how many times I read Indigenous testimony that tried to convey how there was no separation between colonial times and contemporary life. History was lived every day. And its walls could sometimes feel like a prison.

Anna Haebich and Darryl Kickett delve into the Western Australia Aboriginal archive, which includes powerful first-hand testimony from many Nyungar correspondents, detailing the oppression and injustice they suffered at the hands of the authorities. Reading these first-hand accounts, they argue, teaches us about ‘the “structural nature” of problems raised in the Uluru Statement and how these came to be, how the exercise of power festers without integrity and accountability – and about the strong words and courage that helped Nyungar people survive’.

Names and Country (Australian Financial Review)

Names and Country (Australian Financial Review)

Paul Daley’s moving essay on Jimmy Clements and John Noble – where is the memorial to their protest at the opening of Old Parliament House in 1927? – includes remarkable testimony from Noble’s daughter, Ruby, born in 1914, which relates her experience of the Stolen Generations in harrowing detail, evidence Daley tellingly describes as ‘a microcosm of post invasion Australian history’. Joanne Watson explores the bleak history of Palm Island, which in 1918 became a penal settlement for Aboriginal ‘offenders’, many of whom were ‘shipped in truckloads to the island like cattle’. Watson then tells the story of their resistance against slavery-like conditions, connecting it to more recent events such as riots, suicides and deaths in custody, showing how the island’s ‘brutal history’ under successive governments demonstrates the need for a constitutionally-enshrined Indigenous voice to federal parliament.

Yet the burden of this ‘hard history’ is ‘heavy’ and, while Stan Grant wants his children to know and understand it, he also explains why he doesn’t want them to grow up feeling that they are ‘compelled to carry’ it. Like so many other Indigenous Australians today, his children are ‘privileged, urban dwelling, racial and cultural hybrids. They are cosmopolitans.’

In the wake of Uluru, it seems startling that, throughout the 1990s, Australian republicans campaigned for a republic on the basis that it was an entirely separate issue from the calls for Indigenous reconciliation and recognition. Apparently, a new republican constitution involved little more than ‘cutting the last ties’ to the British monarchy. Instead of looking within, the ‘minimalist’ republic promised greater independence through an act of severance alone. Victoria Grieves joins Megan Davis, Gregory Phillips and Indigenous leaders such as Peter Yu in arguing that Australia’s republicans ‘need to think beyond a republic that essentially relabels the existing governance system, in order to enable a process that brings a new constitution with a bill of rights’, a constitution grounded in the principle of ‘shared sovereignty’. Although republicans have long insisted that the two issues are entirely unrelated, as Phillips pithily explains, ‘there can be no republic without a soul … Aboriginal issues are not “a part of” the republican debate, they are the republican debate.’

I was struck by Labor Senator Pat Dodson’s reflection that he has spent most of his life seeking to understand what it is about the Indigenous demand for meaningful recognition ‘that makes it so difficult for successive governments to resolve’. We need a ‘shared narrative’ and a ‘common story’ he pleads. And we need to counter the ‘repeated failures’ of history. The demand for treaties, truth-telling and an Indigenous Voice are indivisible.

Despite all of the setbacks and the failure of successive governments to genuinely negotiate with Indigenous people as ‘enduring political communities with roots on country prior to British colonialism and claims that flow therefrom’, as Will Sanders explains, it’s impossible to read this collection and not come away feeling hopeful. Like Pat Dodson’s conviction that the long, ‘bumpy road’ towards constitutional, political and social justice will ultimately reach a successful conclusion, the determination of contributors to find a way through the current impasse shines through on every page of GR 60. The Turnbull government’s rejection of the Uluru Statement has only galvanised and sharpened the movement for its acceptance.

* Mark McKenna is Professor of History at the University of Sydney. His recent Quarterly Essay Moment of Truth: History and Australia’s Future was reviewed for Honest History by Michael Piggott. Among his earlier work is An Eye for Eternity: The Life of Manning Clark (2011) and From the Edge: Australia’s Lost Histories (2016). He is among Honest History’s distinguished supporters and his chapter in The Honest History Book is titled ‘King, Queen and Country: Will Anzac thwart republicanism?’

This review appears also on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics site, in a Uluru Statement symposium along with contributions from Megan Davis, Cheryl Saunders, Shireen Morris, Christopher Mayes, and Maria Giannacopolous.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.