‘Australia’s national heroes of the electoral system again show there is more to us than Anzac’, Honest History, 13 March 2019

Benjamin T. Jones reviews Judith Brett’s From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia got Compulsory Voting

In 1960, Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies addressed the American-Australian Association in New York. He reflected how, in 1948, he, like most of the press, believed Republican Tom Dewey would win the United States presidency. Truman’s victory was so unexpected that the Chicago Tribune had already printed its morning edition with the incorrect headline, ‘Dewey defeats Truman’. Menzies opined that such an extraordinary result was only possible ‘in a country like the United States, so backwards as not to have compulsory voting’.

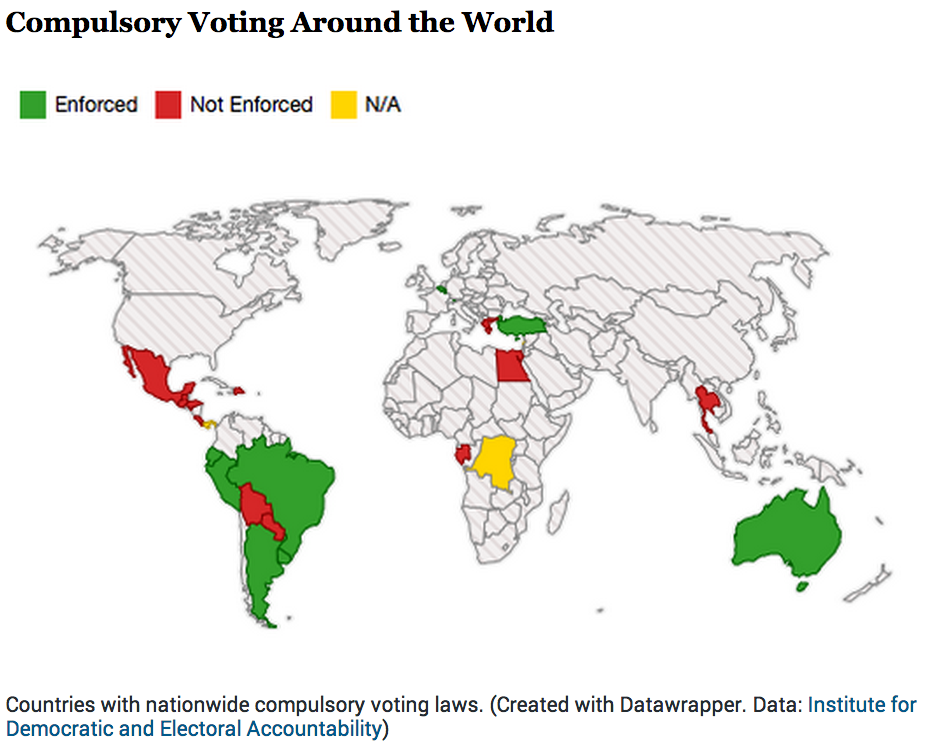

The comment was delivered – and received – in good humour, but it does reveal a deep philosophical rift between the two nations. For the founding fathers of the United States in the late eighteenth century, John Locke was the patron saint and individual liberty the guiding creed. By the time the Australian colonies gained responsible government in the mid-nineteenth century, however, the intellectual winds of the Anglosphere blew in the direction of collectivism, majoritarianism, Chartism, and Benthamism. While Hugh Collins overreaches in presenting Bentham to Australia as Locke to the United States, it is nevertheless clear that the political ideologies underpinning these two British offshoots are distinct from each other and from those of the mother country.

The comment was delivered – and received – in good humour, but it does reveal a deep philosophical rift between the two nations. For the founding fathers of the United States in the late eighteenth century, John Locke was the patron saint and individual liberty the guiding creed. By the time the Australian colonies gained responsible government in the mid-nineteenth century, however, the intellectual winds of the Anglosphere blew in the direction of collectivism, majoritarianism, Chartism, and Benthamism. While Hugh Collins overreaches in presenting Bentham to Australia as Locke to the United States, it is nevertheless clear that the political ideologies underpinning these two British offshoots are distinct from each other and from those of the mother country.

Judith Brett’s new book offers an interesting, original, and readable account of how Australia developed such a distinctive political system. While it would have been tempting to broaden the book’s scope and divert into related narratives, the author is admirably disciplined. She restricts herself to just 183 pages, producing a tight and thoroughly entertaining tale. John Hirst, whose work Brett acknowledges and draws on regularly, has claimed that compulsory voting is the defining element of Australian democracy. A book-length work on how this came to be is a welcome addition to Australian political literature.

Brett does not conceal her pride in Australia’s democratic achievements. She speaks of ‘our history’ (p.3), ‘our compulsory voting’ (p.83), and ‘our Saturday festivals of democracy (p.164). The regular use of ‘our’ and ‘we’ is appropriate in such a book, as Brett stakes her own claim as a citizen, inheritor and co-owner of this democratic heritage. Similarly, her disdain for the democratic shortcomings of the United Kingdom and, especially, the United States, is clear. Both nations adopted the ‘Australian ballot’ (as the secret ballot was widely known in the nineteenth century) but neither have seriously considered preferential voting, let alone compulsory voting. Together with a non-partisan electoral commission, these three characteristics form for Brett a ‘triumvirate protecting our majoritarian faith in democracy’ (p.183). With the United States’ outrageously gerrymandered electoral boundaries, keeping politicians at arm’s length from the running of elections is something Americans ‘can only dream of’ (p.35).

Despite the favourable comparison of Australia with the United States, the book is far from a democratic hagiography. Perhaps the most important chapter is also the bleakest. Chapter 5, succinctly titled ‘Women in, Aborigines out’, explores the way the franchise was expanded on gender, while being restricted on race. The bald-faced racism of the debates is laid bare. The West Australian senator, Alexander Matheson, was particularly notorious in denying First Nations the vote. It was his amendment to the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 that specifically excluded any ‘aboriginal native of Australia’ from joining an electoral roll (unless entitled to under section 41 of the Commonwealth Constitution).

Importantly, Brett notes that there were also some dissenting voices. With an Irish Catholic background, the Protectionist Richard O’Connor was perhaps more sensitive to the plight of the marginalised than were others in the Protestant-dominated parliament. Although strongly supporting White Australia as an immigration principle, he did not support a constitutional restriction on Indigenous votes. Noting that in four of six states Indigenous people could, theoretically at least, participate in elections, he saw no logic in a federal ban. For O’Connor, Australia’s First Nations were ‘perhaps as civilised, and as worthy of the franchise as the white men’ (p.62). Labor’s James Ronald, a Presbyterian minister, complained that denying the vote because ‘a man’s face is black’ is ‘misanthropic, inhumane and unchristian’ (p.65).

Nevertheless, when it came to a vote with Matheson’s explicit restriction on Aboriginal voting remaining, only five members objected. O’Connor, keen to see the Bill pass, was not among them in the end. Brett rightly calls the disenfranchisement of Indigenous peoples ‘complicated and shameful’ (p.56). It would not be until 1962 that the right to vote in federal elections was given to all First Nations people, but without compulsory registration. Extraordinarily, it was not until 1983 that Indigenous Australians came under exactly the same voting laws as non-Indigenous Australians.

Despite the frank admission of how Australia’s democracy has let down First Nations, Brett’s book is, on balance, positive, if not celebratory. ‘Australia was not born on the battlefield but at the ballot box’, she informs readers on page 10. Her conclusion is simply titled ‘We are good at elections’. Again the ‘we’ is significant. Brett’s pride in Australia’s democracy is evident and, for this reviewer at least, not misplaced.

For the last four years, Australia’s bookshop shelves have groaned under the weight of new military histories, popular and academic, coinciding with the myriad of World War I anniversaries. Although a slim volume, this book consciously provides a much-needed counter weight to this brobdingnagian Anzackery. Brett notes that ‘Australians need more than the Anzac story to understand the success of our nation’ (p.182). Indeed we do. How much richer might our civic life be if the Museum of Australian Democracy could loosen ministerial purse strings as effortlessly as the Australian War Memorial does. Australians are accustomed to honouring those who died in service of the nation but do not know the names of many who lived in service of the nation.

Brett reminds us that the women and men who fought to create our Australian democracy are as much national heroes as those who fought in the trenches. Voting is compulsory in Australia and, were it up to me, so would be reading this book.

* Dr Benjamin T. Jones is a Lecturer in History at Central Queensland University. His most recent book is This Time: Australia’s Republican Past and Future (Melbourne: Black Inc, 2018). He with John Uhr and Frank Bongiorno edited and contributed to Elections Matter: Ten Federal Elections that Shaped Australia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.