Douglas Hynd*

‘New Zealand Great War peacemaking history has Trans-Tasman relevance’, Honest History, 5 December 2017

Douglas Hynd reviews Saints and Stirrers: Christianity, Conflict and Peacemaking in New Zealand, 1814-1945, edited by Geoffrey Troughton

Contemporary critiques of Christianity, whether as institution or ideology, commonly involve pointing to it as an unquestionable source of violence. Such critiques usually fail to note the recurring traditions of Christian dissent that have claimed peacemaking and abstention from violence as being at its heart. A minority report certainly, but one with a long history.

Contemporary critiques of Christianity, whether as institution or ideology, commonly involve pointing to it as an unquestionable source of violence. Such critiques usually fail to note the recurring traditions of Christian dissent that have claimed peacemaking and abstention from violence as being at its heart. A minority report certainly, but one with a long history.

Saints and Stirrers: Christianity, Conflict and Peacemaking in New Zealand, 1814-1945, a collection of essays edited by the historian Geoffrey Troughton, documents some of the New Zealand expressions of this dissenting tradition. The essays are laid out to chart an arc of Christian peacemaking in New Zealand from the early days of European settlement through to the close of World War II. While written by New Zealanders for New Zealanders, this collection deserves attention by historians on the Australian side of the Tasman, too. It raises a number of issues that deserve consideration and might cast fresh light on some episodes in Australian history.

Uncritical memorialisation of Australian participation in war, indeed down to the level of individual battles, has become the default setting and a constant public presence in the news media. Just last month we had the 100th anniversary of the battle of Beersheba and the 75th anniversary of the Kokoda campaign. This memorialisation of war has become so egregious as to provide the underpinning of a civil religion (as the late Ken Inglis first pointed out decades ago).

It also has as its shadow side a lack of attention to the stories of those who either as individuals refused to serve in the military, or were members of social movements opposing war. The Troughton anthology offers us a poke in the ribs, intellectually speaking, through highlighting the importance of recovering and retelling the stories of that minority who refused to conform and who challenged the accepted wisdom of the necessity of war by their refusal to participate in it.

What then are the issues raised by the contributors to this volume that help us to develop an agenda for research into peacemaking and opposition to war in Australia? The first issue relates to conflict and peacemaking arising from colonisation and the relationship with Indigenous peoples. The early chapters in Troughton provide accounts of the engagement of Christian missionaries and Maoris in episodes of peacemaking. The appearance of Samuel Marsden in a context of peacemaking may well rouse Australian eyebrows, if not evoke incredulous guffaws, but his place and persona in New Zealand history is very different to what it is in colonial New South Wales. Critically these chapters represent an acknowledgment of the conflictual character of the European occupation of Aotearoa and an exploration of the active agency of both Maoris and missionaries in seeking a resolution of specific conflicts.

The relevance to research in the Australian context is that our increasing recognition of the reality of the Frontier Wars between the first nations and the European invaders paradoxically opens the door for recovering and retelling stories of attempts at conflict resolution. Without the acknowledgement of the reality of war and violent occupation the possibility of identifying and retelling stories of peacemaking has been overlooked in Australia.

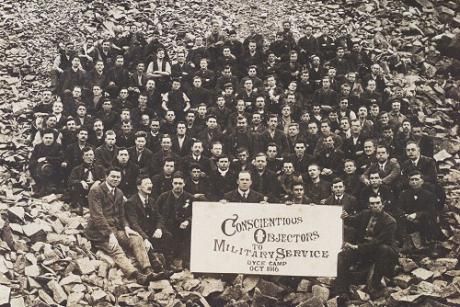

The second issue concerns the implications of the referendums on conscription in Australia during World War I. The accounts offered in the essays on conscription in New Zealand during the war, particularly the heavy-handed treatment of dissidents by both government and judiciary, raises an interesting hypothetical for Australian historians: what would have been the result had either of the conscription referendums in Australia been passed narrowly, followed by an increased number of objectors who received treatment along the lines of that in New Zealand? The potential for further political upheaval and long-lasting social division arising from the campaigns to a level well beyond those generated by unsuccessful referendums would certainly have been present. Maybe we dodged a bullet there.

The third issue concerns the relationship between the state and religious communities when their respective claims come into conflict. The essays dealing with conscription in New Zealand during the World Wars examine in some detail the differing ways a variety of Christian sects and their members engaged with government and the judiciary around the issue of conscientious objection. These essays document the increasingly powerful reach of the state in the 20th century and the ways it can enforce its will when confronted with religiously empowered opposition that refuses to recognise the overriding claims of the state, claims that from the point of view of dissidents can only be considered as being blasphemous.

NZ objectors, 1916 (danieltalis)

NZ objectors, 1916 (danieltalis)

What also needs to be noted in this context is the difficulty that magistrates and the Defence Department in New Zealand had in coming to grips with the theological arguments and ecclesiastical identities of disorganised rather than organised religion. Agents of the state were much more comfortable in dealing with institutionally structured forms of religiosity, rather than unstructured though clearly tenacious communities of practice and belief. These essays make clear how much courage was required to maintain a conscientious stance against participation in war in the face of legal and social pressure. The line between the principled civic courage of a minority and what may be regarded as ratbaggery – at least by the majority – can be hard to discern and represents an interesting challenge to the historian.

The authors in this collection of essays get up close to individuals and religious groups in exploring the various motivations in Christianity for dissent against war. They also display well documented research. The essays serve as a reminder that Christianity can be strongly implicated at the level of ideology and community in driving and sustaining those opposed to state violence while at the same time being drawn on as a resource by the state to further its own sacral project.

These essays offers an agenda for refocusing historical research in Australia on those who have opposed the state’s call to participate in war. A research agenda with this focus, even if it begins with groups and individuals motivated by Christianity, will also bring into focus those who have resisted war on other grounds. All of these are stories we need to hear and tell in a time in which remembering war and using the fear of violence to underpin the accumulation of executive power equally dominate both public discourse and social imagination.

* Dr. Douglas Hynd is an Adjunct Research Fellow at the Australian Centre for Christianity and Culture, Canberra. He has previously written for Honest History on the theological aspects of Anzac, the Martin Place siege, and asylum seekers, and reviewed the Anzac number of a periodical.