Stephen Holt*

‘Another Philipp (sic) encounters Australia: one of many stories in a rich second Dunera volume’, Honest History, 30 September 2020

Stephen Holt reviews Dunera Lives: Profiles, by Ken Inglis, Bill Gammage, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter with Carol Bunyan

Academic life in Cold War Australia is a subject that is bound to be of interest to people who support the Honest History movement. We associate the Cold War with fear and paranoia, emotions which have a chilling effect on truth and candour. Given this background, it is useful to learn more about how university people at the time dealt with Cold War pressures to conform.

The recent appearance of the second and final volume of Dunera Lives – this one is subtitled Profiles, the first was A Visual History (reviewed here) – a project commemorating the Jewish exiles transported to wartime Australia in the vessel of that name, is especially welcome when viewed in this context.

The recent appearance of the second and final volume of Dunera Lives – this one is subtitled Profiles, the first was A Visual History (reviewed here) – a project commemorating the Jewish exiles transported to wartime Australia in the vessel of that name, is especially welcome when viewed in this context.

In the spring of 1940, hundreds of exiles from the Third Reich disembarked from the Dunera in Melbourne and Sydney. Initially classified and incarcerated as enemy aliens, they regained their freedom and settled down to live and work in wartime Australia and, in some cases, across the world.

The first volume of Dunera Lives provided a visual record of the refugees’ experiences as and after they were transported to Australia. The second volume, now before us, provides individual profiles of some 20 of the Dunera refugees, some of them well known, like the economist Fred Gruen, the political scientist Henry Mayer, the sculptor Erwin Fabian, the anthropologist Leonhard Adam, and the composer Felix Werder, others not so much.

In some ways, it is the stories of the less well-known men that give the volume extra gravitas and nuance. The volume highlights the many and varied ways in which members of the Dunera contingent contributed to building up the material and intellectual resources of Australia after peace came in 1945. As the blurb says, the volume ‘presents the voices, faces, and lives of 20 people, who, together with nearly 3000 other internees from Britain and Singapore, landed in Australia in 1940’.

The book, like the first volume, is handsomely produced by Monash University Publishing and there is much supporting material on the excellent Dunera Stories website. The leader of the team that worked on Dunera Lives was the late Professor Ken Inglis. (Indeed, his colleague on the cover, Professor Jay Winter, says Inglis was the author of every profile.)

The energy propelling Professor Inglis’ distinguished academic career can be traced all the way back to 1948 when he wrote a student essay on Machiavelli and the essay deeply impressed Franz Philipp, a Viennese art historian who knew a lot about the Renaissance. Philipp, a Dunera alumnus who had fetched up at the History Department at Melbourne University, suggested to the young Melburnian that he might have a future as an academic.

Dunera Lives, as masterminded by Inglis, would surely never have seen the light of day had not Franz Philipp influenced Inglis in the way that he did. It is worthwhile on this occasion therefore to focus on the Dunera Lives profile of Philipp in particular. By doing so we can begin to test how the whole project stacks up as a source of information and explanation covering an important group of post-war, Cold War Australians. (Remember, though that a goodly proportion of the Dunera cohort left our shores after the war.)

Philipp’s life and career certainly shows in some detail how the stimulating impact of the Dunera refugees spread throughout their new community. There were fruitful connections with marriage partners, colleagues, students and children.

History is a funny thing. The post-war Australia which freely opened up to Philipp – he ended up as a Reader in Fine Arts at Parkville – seamlessly overlapped with Cold War Australia, where an obsession with subversion by sinister outside forces was ever present.

Stubborn Cold War perceptions came into their own when Philipp, to his chagrin, failed to fulfil his strongest career ambition, which was to become a Professor of Art History at a prestigious university in the United States. He did not pursue his dream because of concern that allegations of unpatriotic communist connections would dog him were he to try to move to the United States.

The security issues, interestingly enough, did not immediately emanate from Philipp himself, but from his wife. June Rowley, then a senior tutor in Melbourne’s History Department, married Philipp, her colleague, in 1948. She continued to teach in the Department after becoming a wife and then mother of their two daughters. This juggling of career and family was rather unusual for the time.

The profile in Dunera Lives is as much about June Philipp as about her husband. She and Franz were a close if ‘contrasting’ couple. Franz’s experience of the Third Reich caused him to shy away from political or ideological passion. June, in contrast, was always more forceful, never forswearing the left-wing views of her youth.

Sadly, the profile perpetuates the erroneous view that June was ‘called before’ the Petrov Royal Commission in 1954. It is highly likely that the June so summoned was in fact June Barnett, a public servant from Canberra.

The profile also says that June Philipp ‘remained active in the CPA [Communist Party of Australia] into the 1950s’. This may or may not be true but it can be more usefully said that the best expression of June’s leftism came in the 1940s when she was involved in the then famed Melbourne University Labour Club, a group which was open to Communists and non-Communists alike. She took part in discussions with Jim Cairns and other leading MULC supporters, in which the question of whether or not the Australian labour movement was or ever had been radical or socialist was canvassed earnestly, including through a close examination of original historical material from colonial times. (Noel Ebbels’ pioneering collection of documents, The Australian Labor Movement, 1850-1907, came from this period.)

June Philipp was always known for being forthright. A 1955 letter to her former colleague Manning Clark, in which she dressed him down because of his swelling desire to be accepted as a Dostoevsky-like prophet, is truly memorable.

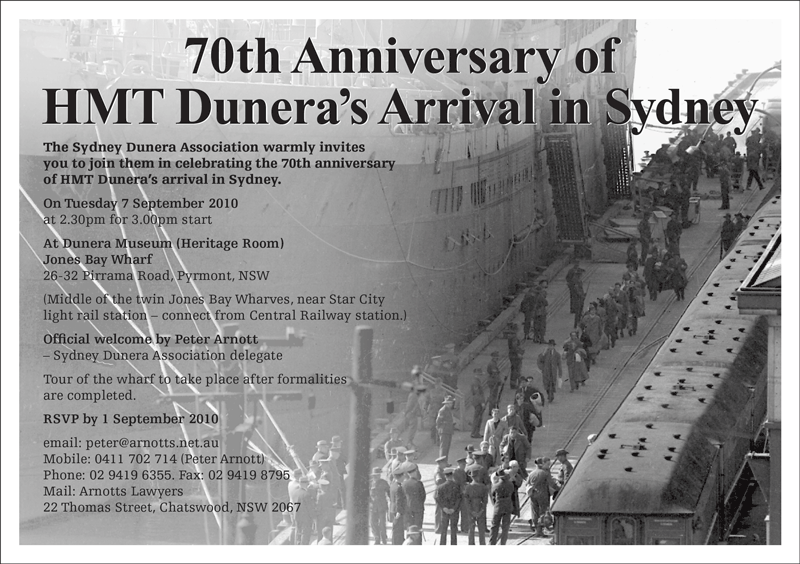

Dunera 70th anniversary promotion, 2010

Dunera 70th anniversary promotion, 2010

June’s continuing to uphold her beliefs prevented Franz, ever cautious because of his traumatic past, from applying for a professorship in the United States in the 1960s. Always stressed and hard-working to the end, he died in London in 1970, while on sabbatical leave. June continued on as a senior academic. Having acquired a doctorate in history, she transferred to La Trobe University, where she spent the rest of her productive career.

Ken Inglis, the principal begetter of Dunera Lives, died towards the end of 2017. His work on the profile of Franz Philipp, which covered June as well, was, the second volume notes, Inglis’s ‘last academic endeavour’. It came almost 70 years after he wrote that undergraduate essay on Machiavelli. It is a wonderful tribute, as indeed are the whole two volumes.

This assessment of one Inglis-initiated profile can only hint at the enduring impact of Franz and June Philipp on the people they encountered and interacted with in Australia. The couple, without at all being lifeless, embodied critical thought, something which is ever endangered and yet which is always springing up anew in the unlikeliest quarters. Beyond the Philipps, the whole book, like the first Dunera volume, promises much rich history and biography.

* Stephen Holt is a Canberra writer. He is the author of biographies of historian Manning Clark, labour movement stalwart Lloyd Ross, and (with Ross Fitzgerald) journalist Alan Reid, and of numerous media articles, such as this one about growing up in Canberra. For Honest History, he wrote about a Canberra character, Douglas Berneville-Claye, and reviewed Terry Irving’s biography of Vere Gordon Childe.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.