Stephen Holt*

‘A genuine Aussie digger: Vere Gordon Childe 1892-1957’, Honest History, 19 April 2020

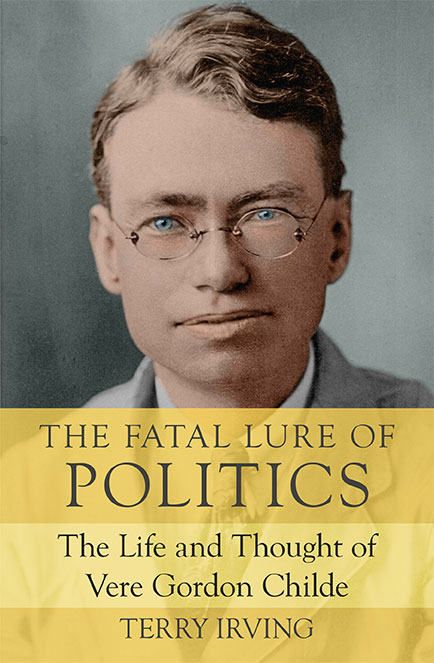

Stephen Holt reviews The Fatal Lure of Politics: The Life and Thought of Vere Gordon Childe, by Terry Irving

The Honest History project, since it began, has fostered a truer understanding of the impact on the Australian people of the Great War of 1914–18. Honest History’s constituency therefore is bound to welcome Terry Irving’s newly published study of the Australian scholar and activist, Professor Gordon Childe, given that Childe’s life of thought was turned upside down by his need, starting in 1916, to resist our involvement in the war.

Irving’s living engagement with Childe dates back decades. In 1957, as a teenaged campus radical, he witnessed Childe receiving an honorary degree at Sydney University, Childe’s alma mater. Childe was a living socialist icon at a time when the Australian Labor Party, led by Childe’s old friend, Bert Evatt, was at a low ebb, having split asunder after Evatt denounced his former ally, BA Santamaria.

Irving’s living engagement with Childe dates back decades. In 1957, as a teenaged campus radical, he witnessed Childe receiving an honorary degree at Sydney University, Childe’s alma mater. Childe was a living socialist icon at a time when the Australian Labor Party, led by Childe’s old friend, Bert Evatt, was at a low ebb, having split asunder after Evatt denounced his former ally, BA Santamaria.

This emotional connection means that reading Irving’s account pays off in the end. At times there is slightly too much exegesis and earnest commentary. There is also the problem that Childe destroyed most of his private papers in the 1950s. This means that Irving is forced to speculate at times about what Childe may have been doing or thinking at a crucial moment. But the reader is drawn on. Childe’s involvement in significant events and matters makes for compelling reading.

Childe was involved in the world of learning and uplift from the beginning. The son of an Anglican minister, he entered Sydney University in 1911, enrolling as a student of Classics and Philosophy. A budding Christian socialist, he performed secretarial work for the Labor Party in the 1913 state election, along with his university cobber, Evatt.

At university, Childe was bent on becoming a serious student of ancient Greek civilisation. He mastered the written historical sources and then fixed his attention on Greek prehistory and its archaeological record. In effect, he was bent on becoming a digger. But in prewar Sydney, decades before John Mulvaney or Lake Mungo, academics quietly assumed that there was nothing of note to dig up in Australia. Would-be archaeologists had to head off to England if they wanted to kick-start an academic career.

So, in the fateful year of 1914, Childe found himself enrolled as a student at Queen’s College at Oxford. He researched eastern influences on early Greek history and was awarded a B. Litt in 1917.

Childe was a citizen as well as a scholar, and life in wartime Britain radicalised him. Arriving as a temperate Fabian socialist, he was driven further to the left and towards embattled activism once the issue of mass military recruitment became ever more politicised and personalised. He came to describe the Great War as ‘destructive to civilization and true liberty’, his twin gods. He supported conscientious objectors and, as a result, his name appeared in security files. He was blacklisted. He was obliged to leave England when his course at Oxford ended.

Back home, Childe’s status as a rare tertiary-educated socialist led to him getting gigs as a lecturer, writer and policy and political advisor in Sydney and Brisbane as wartime pressures caused the labour movement to be ever more receptive to new ideas. An incoming anti-Labor state government in Sydney sacked him as a public service research officer in 1922, but by then he had returned again to the mother country, via a post in the NSW agent-general’s office in London.

For the next few years, Childe mixed with and swapped thoughts with progressive intellectuals in London. He had already written the draft of a book (How Labour Governs), which incorporated his ideas and impressions as a consenting middle-class socialist in Australia. Published in London in 1923, this tract spoke directly to his friends. Sympathetic people in the UK, unlike in Australia, had yet to live under a Labo(u)r Party government; Childe could tell them what might well happen.

Studying recent Australian political history as presented in How Labour Governs would have been a chastening experience for many of Childe’s fellow radicals. For an all too brief moment, anti-conscription and anti-war zeal had created a dazzling vision in Australia. Regimented majorities in parliament, it was hoped, could be utilised to back in a system of industrial democracy. But the presence of serial rats in Labor’s ranks, led by Billy Hughes, blighted such hopes.

Almost like clockwork, the insistent messaging in How Labour Governs was amply borne out just a few years after the book was published. In 1929, faced with an impending financial and economic crisis, the UK’s first ever Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, formed a national coalition dominated by Tories.

By then, Childe had at last capitalised on his formal qualifications. He was the Abercromby Professor of Archaeology at Edinburgh University. He spent half the academic year lecturing and the other half supervising archaeological digs in Scotland and conducting research in European museums.

Childe now professed to ‘loathe’ excavation work. He continued to supervise it but was also keen to write books. He knew he could speak to a wider non-specialist public; he had a grand vision to expound. He wanted to trace how advances in tool-making and other forms of craftspersonship had spread out from early non-European societies to prehistoric Europe. His was a story of progress culminating in the revolutionary emergence of food producing and urban communities.

Childe’s world picture was widely described as materialist or Marxist and he did not disagree. He was careful though to differentiate between Marxism as a ‘methodological device’, which he was drawn to, and Marxism as a ‘set of dogmas’, which he had no time for at all. He got on well with individual British Communist scholars while dismissing the Communist Party of Great Britain as ‘quite hopeless’.

Childe long had a soft spot for the USSR. For much of his adult life he saw it as a mighty work in progress. As an archaeologist, he yearned to delve into the ‘prehistoric treasures’ buried beneath the soil of ‘socialised Eurasia’. Yet research visits to the USSR led him to conclude that Soviet archaeology lacked a sound material foundation. It was, he privately noted, bedevilled by practical problems such as poor excavation techniques and a neglect of aerial photography.

At the end of the day, theory had to defer to archaeological praxis. Childe, to be true to himself, needed to be a digger and not a dogmatist. What Happened in History brought his thoughts to countless readers.

It was in a wistful mood that Childe, now a distinguished retired academic, ended his long absence from Australia and travelled back here in 1957. In October of that year, his dead body was found at the foot of Govett’s Leap in the Blue Mountains where he had loved to stay and visit when he had been a hopeful young man before a world war blighted everything.

It was in a wistful mood that Childe, now a distinguished retired academic, ended his long absence from Australia and travelled back here in 1957. In October of that year, his dead body was found at the foot of Govett’s Leap in the Blue Mountains where he had loved to stay and visit when he had been a hopeful young man before a world war blighted everything.

Childe was a truly significant Australian. Terry Irving has recreated his life, work and thought with great care and precision. The odd personal touch – such as Childe’s brush with the 1919 pandemic – adds to the book’s readability. That brief academic encounter at Sydney University in 1957 has paid off handsomely.

* Stephen Holt is a Canberra writer. He is the author of biographies of historian Manning Clark, labour movement stalwart Lloyd Ross, and (with Ross Fitzgerald) journalist Alan Reid, and of numerous media articles, such as this one about growing up in Canberra. For Honest History, he wrote about a Canberra character, Douglas Berneville-Claye.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.