‘“German frightfulness” from the Australian Light Horse, Egypt, 1919’, Honest History, 18 March 2019

One hundred years ago this month the fabled Australian Light Horsemen led the charge to put down the Egyptian national revolution.

On 8 March 1919, the British arrested Saad Zaghlul,[1] the Gandhi of Egypt’s independence movement, and next day deported him to Malta, along with his closest colleagues. In response Egyptians rose literally as one to demand the end of British rule.

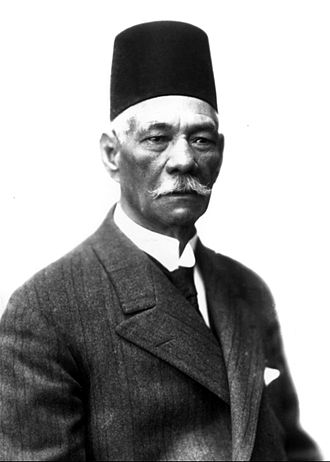

Saad Zaghlul (Wikipedia)

Saad Zaghlul (Wikipedia)

Zaghlul had been demanding (and the British government refusing) that Egyptians be allowed to send a delegation to the Versailles peace conference to argue for Egyptian independence. The victorious Allies had, after all, proclaimed the right of national self-determination as one of their principal war aims.[2]

The rising began in Cairo and Alexandria, with strikes and demonstrations by students, lawyers, civil servants and transport workers. It then spread to the countryside where ‘soviets’ or makeshift councils were created to administer towns and regions. Peasants and landless labourers invaded the palaces and granaries of the large landowners and redistributed their stores and animals.[3]

There was much more that was admirable in the rising. There were few atrocities committed against the British and less than a handful of British civilians were killed. Copts and Muslims worked side by side and for the first time women met and demonstrated in public. This feminist awakening began with upper-class women who, it was said, organised on the telephone and arrived at their marches by chauffeured car. Nonetheless, they defied police bans and were joined in the revolution by their more plebeian sisters from the working class and peasantry. (In the early 1970s an Egyptian feminist scholar listed the names of women from the working class and peasantry who were killed as participants during the March days. Conceivably, some of these women were cut down by Australian bullets.)[4]

Into this insurgent maelstrom for freedom rode the Australian Light Horse in the service of the British Empire, arriving in the Nile Delta on March 16.[5] For three months, from March till June 1919 – well after the war was over, remember – the Light Horse roamed the Delta, raiding and patrolling hundreds of villages. Occasionally, they would torch the villages. They organised the forced restoration of railways, helped break strikes, broke up public meetings, arrested and flogged hundreds of ‘seditious agitators’, and regularly seized ‘native propaganda’.[6] In some instances they machine-gunned and shot down scores of ‘natives’.

It is hardly surprising that there is no mention anywhere in the Australian War Memorial of this less than glorious chapter, although the Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 says (in a one page Appendix) the troopers ‘went out gaily on a new enterprise’.[7] The context was that in 1919 the British Empire found itself threatened by independence uprisings in India, Ireland and Egypt. Of these three the Egyptian revolt was the most widely supported.[8]

The Egyptian revolt caught the British unawares and with few troops to suppress it. Most of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force that had vanquished the Turks had been repatriated home to Britain. Even its commander, General Sir Edmund Allenby, was in Europe on leave. The Egyptian Army and police were considered unreliable. In desperate straits, the authorities even considered using Turkish prisoners of war.[9] However, twelve of the fifteen Australian Light Horse regiments were still in Egypt and Palestine awaiting boats home. Ten regiments were swiftly dispatched to the Nile Delta with the others sent to Cairo and Upper Egypt.[10]

Throughout the Delta, peasants had burned railway stations and ripped up rail lines. There was logic in this. During the war the British had established in Egypt what has been described as ‘a military extractive state focused on the railway and telegraph’.[11] Men, animals, materials and foodstuffs were at first acquired voluntarily for the war effort. But when these items were not forthcoming, the British resorted to compulsory requisitioning. The railways were, of course, the means to carry through the British orders.[12]

Injustices were compounded by food shortages for the ordinary Egyptian as the war ground on. There was widespread malnutrition in both town and countryside. In 1915 and 1918, for the first time in more than a quarter of a century, deaths outnumbered births in Egypt. Wheat consumption had dropped from 95.9 kilos per capita in 1913 to 61.7 in 1918. Overall consumption of cereals and pulses had dropped by a fifth.[13] As the British admitted, ‘The entire economy and society of Egypt had been strained for the sake of the British war effort’.[14]

Allenby (Wikipedia). See also this video of Allenby, wife and tame stork, Cairo, 1919

Allenby (Wikipedia). See also this video of Allenby, wife and tame stork, Cairo, 1919

Few villages would have escaped the British demands; the Egyptian Labour Corps, for instance, which laid the rail track across the Sinai, comprised over 100 000 men. The Camel Corps had another 25 000 men. The means of getting arms, ammunition, reinforcements and food to the Australian troops fighting the Turks in the Sinai and Palestine were the railways built by these Egyptians.[15] More than a million peasants were caught up in this unpaid labour scheme and hundreds of them died of exposure behind the battle lines in the harsh winters of 1917 and 1918.[16]

If Egyptians had any hopes these sacrifices might be appreciated by the Australians they were deluded. Egyptian nationalists did appeal to the hoped-for better nature of the Australian horsemen with leaflets calling on them to support the democratic aspirations of the Egyptians. Some hope. As Brigadier General Lachlan Wilson, the commander of the main Australian force based at Zagazig, triumphantly noted, ‘not even our most rabid socialist’ showed any sympathy for this call for solidarity.[17]

Even British residents were repelled by the ‘obnoxious’ racism of the Australians troops. In Cairo, one of the main concerns of the British police chief, Thomas Russell, was to keep the Australian troops away from the Egyptians as much as possible. When Allenby decided to try to defuse the uprising by releasing Zaghlul and his comrades in early April, the people of Cairo thronged the streets in wild celebration at their victory. This provoked a reaction from Australian troops whose attacks on the celebrating crowds killed eight to ten civilians. ‘There were two bad scraps in the night caused by infuriated Australians getting loose and eight or ten Egyptians getting killed’, Russell recalled.[18] Three weeks earlier, Russell had defused a similar situation by convincing Australian troops to return to barracks.

There can be little doubt that the Australian troops knew what they were doing. ‘We knew we had the whole of the native population of Egypt against us’, Wilson wrote after the war.[19] Circulars to officers and other ranks from the British High Command openly admitted that the independence movement had near universal support. But orders were orders.[20]

And those orders were merciless:

If it is necessary to use force to prevent disorder or to quell disturbance it is of vital importance that force should be applied promptly and without hesitation, that the force employed and that the action taken should be amply sufficient to ensure that the object to which force is applied is quickly and completely attained.

The same general order adds, ‘Hesitation and feeble action will be useless and dangerous’.[21] More specifically troops were ordered to shoot anyone interfering with the rail lines and to burn neighbouring villages.[22]

The Australians implemented the orders to the letter. On 16 March, Captain Henry Palmer, 10th Light Horse Regiment, reported from Minat al-Qahm:

At 10.45 upon a train approaching from Cairo a large mob of about 900-1,000 made a rush for the level crossing. Stones and bottles were thrown and they were refusing to stop 4 yards from the rails. Lt McGregor and others were being hit by stones, rioters were also attempting to gain the platform from the end near the level crossing … It was then that Lt McGregor gave the order “Fire” and “Cease Fire” when the mob broke. The firing lasted about one minute … 39 natives were killed and 25 wounded. The Egyptian Police assert that 40 were also drowned but my men only saw one sink of the many who jumped into the canal.[23]

The judicious and usually restrained historian of these events, Suzanne Brugger, did not hesitate to comment: ‘Fifteen troopers had managed to kill forty natives in sixty seconds’. Only one trooper was slightly wounded in the neck.[24]

Officers of the 1oth Light Horse, Lebanon, December 1918. Captain Palmer is standing, last on the right. (AWM C954701)

Officers of the 1oth Light Horse, Lebanon, December 1918. Captain Palmer is standing, last on the right. (AWM C954701)

‘The lesson had been severe but there was no more rioting,’ wrote General Wilson later.[25] No, sadly, he was wrong. On 22 and 23 March Australian troopers clashed with crowds trying to cut rail lines not far from Zagazig, the headquarters of the Light Horse Third Brigade, killing, by their own reports, at least ninety Egyptians. A repair train had been stranded and the Australian troops had been detained unharmed in a village. Two trains, preceded by rail trolleys with mounted machine guns, were sent to bring the original train and troopers back. A mounted troop was also dispatched. In this operation, in two separate incidents, sixty Egyptians were killed by machine gun fire and the mounted troopers killed another thirty.[26]

There were other skirmishes where the numbers shot down were mercifully fewer. In the first three weeks in the East Delta, 342 villages were visited. ‘Several patrols were stoned with the consequence that some of the natives were killed and wounded’,[27] Wilson recalled.

The firm finger on the trigger was motivated by the imperialist doctrine of the time that the only language that ‘natives’ understood was a burst of extreme violence.[28] Wilson, as the commanding officer of the main Light Horse concentration in the Delta, made this explicit in his later account of the suppression of the ‘Egyptian Rebellion’. The natives – they are almost always ‘the natives’ – ‘did not understand anything except force’ and ‘what they required was some of the German frightfulness which our Teutonic friends exhibited towards the foreign civil populations under their control’.

Accordingly, Wilson boasted, ‘any physical opposition to our troops met with prompt punishment and in no single district had we to dispense such punishment twice. A single lesson was all that was required.’ That wasn’t strictly true, but the boast gives a good indication of the mindset of the Light Horse commanders.

Wilson went on to criticise the liberal policy of the British in Cairo for tolerating public meetings and demonstrations, which resulted in the city becoming ‘the most turbulent part of the country’. There was no such nonsense in the Delta: ‘There were no processions or public meetings of rebels in our area and no rebel flags were aloft within the range of our vision’.[29]

These were not the aberrant orders and thoughts of a panicked and racist officer. They reflected the received military doctrine of the British Empire. As one historian put it recently: ‘In C.E. Callwell’s classic manual Small Wars, first published in 1896, the author argued that ‘The lower races are impressionable. They are greatly influenced by resolute bearing and a determined course of action … Uncivilised races attribute leniency to timidity.’[30]

There is evidence that the Australians carried out their orders with too much zeal. Certainly at the end of March, Allenby, now as the Special High Commissioner, issued orders that no more villages were to be burned.[31] In the sparse records at the Australian War Memorial, it is impossible to tell how many villages were burned. The best-known cases were at Azizia, south of Cairo, where a village of over 170 dwellings was burned down after a dawn raid by troopers searching for arms on 23 March, and at Abu Akdar, where a village covering 18 acres was burned a few days later.[32] There was a military inquiry into the Azizia incident, but it was concerned, not with the arson or the killing of three villagers, but with allegations of pilfering and sexual harassment by the troopers.[33]

Wilson (SLQ Blogs/AWM). Wilson also appears in a Septimus Power painting of Light Horse and other officers mounted.

Wilson (SLQ Blogs/AWM). Wilson also appears in a Septimus Power painting of Light Horse and other officers mounted.

Another regrettable feature of the pacification offensive was the flogging of ‘agitators’. Australian patrols were arresting independence activists right up to the Australians’ final departure from the Delta at the end of June and these men were liable to be sentenced to imprisonment or flogging after judgment by summary military courts composed of officers on the spot.[34]

It is hard to conceive at this remove of Australian troops using the whip to punish citizens of another country. Yet, in Egypt in 1919 it was a perfectly acceptable punishment for truculent or uppity natives. In the case of Saft El Meluk, after a sniper ambushed a patrol and killed two Light Horsemen, all the men – some 250 of them – from a nearby village were rounded up and all given twenty lashes.[35] ‘Many died of the laceration’, according to an Australian reporter in Egypt.[36]

Saft El Meluk was an extreme example. The report from the Zagazig sector dated 7/4/19 is typical: ‘Rosetta reported restless. 18 public floggings have been given at Shud Rakhit and 28 at Damanhour.’ Most of the worst encounters took place in the first two weeks of the Australian deployment. By the end of March, villages in the Delta were quiet and peasants were being rounded up to repair the rail and telegraph links. There was another upsurge in the revolt in the second week of April, though, which coincided with Allenby’s decision to release Zaghlul and his comrades and allow an Egyptian delegation to proceed to Versailles. The rallies and marches then were as much in celebration as anger.

Estimates of the numbers of Egyptian killed during the suppression of the March uprising vary from 800 to 3000. In mid-May the British government admitted to approximately 1000 Egyptians killed. This toll can be compared with 463 killed in the 1919 uprising in India, a country fifteen times as large. Kitchen’s conclusion – ‘In a comparative sense it is clear that the suppression of the Egyptian revolution represented one of Britain’s bloodier post-war imperial campaigns.’[37] – is difficult to argue with. For their part the Egyptians were remarkably pacific. The British government reported that 27 ‘British’ soldiers and four civilians lost their lives, along with nine Indian soldiers and 31 foreigners.[38]

From the middle of April to the end of June, Australians continued intensive patrols, arresting, fining, jailing and flogging ‘agitators’, confiscating ‘seditious’ literature and attempting to break sporadic strikes by railway men and civil servants. By the end of May, the Light Horse regiments in the east Delta area reported arresting over 500 agitators in April and May. A taste of the punishments meted out is given in a report for the last week of May in the Belbeis sector: ‘7 arrests made and 74 cases disposed of, the sentences total 220 years, 200 lashes and 20 strokes’ (strokes being lashes to minors).[39]

How successful were the Light Horse men in suppressing the revolt? It is hard to gauge at this distance the relative weight to give to the impact of the massacres and armed patrols, as against the efforts by the Egyptian notables to end the destructive violence. ‘The propertied classes played a role in aborting the uprising’, writes Walid Kazziha, professor of political science at the American University, Cairo. ‘The Wafd [Zaghlul’s party] at first took a non compromising stand but as the attacks of the peasantry began to touch the interests of the upper landowners, a split occurred in which the upper echelons first split from the Wafd, then the Wafd leadership itself began to compromise.’[40]

Nationalist leaders not only called for restraint, but organised their own law-and-order police. Clerics from the Islamic university of Al-Azhar in Cairo also issued calls for restraint.[41] The beginning of the harvest season in April, followed by Ramadan, also diverted the rural unrest.

Suzanne Brugger argues that the Australians’ heavy-handed pacification efforts only alienated Egyptians in the Delta. ‘Even the most charitable view of the Australian actions during 1919 must admit that politically they brought disastrous results.’[42] What is clear is that any success by the troopers was temporary – as Gullett admits in the Official History. Right up until the moment the Light Horsemen left they were still raiding villages, arresting and punishing ‘agitators’ and confiscating ‘seditious’ literature. And Egyptians were still going on strike in the towns of the Delta.[43]

By this time the independence movement had switched its focus to the cities and bigger towns. Assassinations[44] were mixed with demonstrations, strikes and boycotts for the next two years until Allenby and the other high officials on the spot concluded that Egypt was ungovernable and another revolution imminent if home rule was not conceded. In February 1922, the British unilaterally extended limited independence to Egypt. In the first elections, Saad Zaghlul and the Wafd (or Delegation) party swept to office.[45]

What this appalling intervention by the Light Horse does is confirm the imperialist nature of World War I. The Diggers and the troopers had supposedly gone to war and sacrificed so much for the freedom of small nations. But in Egypt they were happily suppressing a small nation struggling for its freedom from the British Empire. It was not to be the last time Australian troops played such a role.

Egyptian women protesters, Cairo, 1919 (Nabila Ramdani blog)

Egyptian women protesters, Cairo, 1919 (Nabila Ramdani blog)

* Hall Greenland is the author of Red Hot: The Life and Times of Nick Origlass, 1908-1996 (Wellington Lane Press, Sydney, 1998). He is a dual Walkley Award winner who worked at The Bulletin and The Week.

Endnotes

I would like to acknowledge Suzanne Brugger’s Australians and Egypt, 1914-1919, Melbourne University Press, 1980. This magisterial account is an indispensable platform for any understanding of the events of 1919 in Egypt. I also acknowledge the invaluable help of staff at the research centre at the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia who tracked down the files, Egyptian Revolutionary Disturbances 1919, AWM25 183/12, Parts 1-5, containing the sparse records of the Light Horsemen’s activities in Egypt in 1919.

[1] Zaghlul was an interesting character. After successful careers as journalist and lawyer, he became the leading political figure in pre-war Egypt. He became something of a favourite with the legendary British consul in Egypt, Lord Cromer, who saw in him a Westernised native and product of benevolent British rule, although Zaghlul himself justified his attachment to parliamentary and responsible government by reference to Islam. Unlike other nationalist leaders, he was not from a family of large landowners but was the son of a village omdah (or mayor) of middling means. These relatively humble origins meant he could talk the language and dialects of plebeian Egyptians. His willingness to condone intimidation (and perhaps worse) of collaborators and political strikes during these years has earned him the disfavour of liberals as well as conservatives.

[2] MW Daly, ‘The British occupation, 1892-1922 ’, MW Daly, ed., Cambridge History of Egypt: Volume II: Modern Egypt, from 1517 to the End of the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, 1998, online edition 2008, pp. 246-51. See also: Afaf Lufti Sayyid Marsot, A Short History of Modern Egypt, Cambridge University Press, 1985.

[3] Saker El Nour, ‘Les paysans et la Revolution en Egypt: du mouvement national de 1919 à la révolution nationale de 2011’, Revue Tiers Monde, 2, 4, 2015 (Issue 222), pp. 49-66.

[4] Nabila Ramdani, ‘Women in the 1919 Egyptian Revolution: from feminist awakening to nationalist political activism’, Journal of International Women’s Studies, 14, 2, March 2013, pp. 39-52. A work in Arabic by Ijlal Khalifa is cited as listing the names of women martyrs of 1919. See also: Brugger, pp. 103, 108; Nawal al-Sa’adawi (trans. Sherif Hetata), The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World, Zed Books, London, 1980, p. 176; Sir Thomas Russell Pasha, Egyptian Service, John Murray, London, 1949, p. 201.

[5] LC Wilson, The Third Light Horse Brigade, Australian Imperial Force, in the Egyptian Rebellion 1919, The author? Brisbane? 1937.

[6] See: Egyptian Revolutionary Disturbances, AWM25 183/12ff. Files labelled ‘Egyptian Revolutionary Disturbances 1919’.

[7] HS Gullett, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918: Volume VII: The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 10th edn, 1941, p. 793.

[8] John Gallagher, ‘Nationalisms and the crisis of Empire, 1919-1922’, Modern Asian Studies, 15, 3, 1981, pp. 355-68; John Gallagher, The Decline, Revival and Fall of the British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 1982, pp. 73-153.

[9] Summary of events in Egypt from November 1918 to April 1919, 17 April 1919, FO 608/213, cited: Willow Berridge, ‘Object lessons in violence: the rationalities and irrationalities of urban struggle during the Egyptian Revolution of 1919’, Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, 12, 3, Winter 2011.

[10] Wilson, p. 5.

[11] James E. Kitchen, ‘Violence in defence of Empire: the British Army and the 1919 Egyptian Revolution’, Journal of Modern European History, 13, 2, January 2015, pp. 249-67.

[12] Brugger, pp. 84-98; Russell, pp. 190-206.

[13] Ellis Goldberg, ‘Peasants in Revolt – Egypt 1919’, International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 24, 2, May 1992, pp. 261-80.

[14] Goldberg, p. 271.

[15] Saker El Nour.

[16] Goldberg, p. 268.

[17] Wilson, p. 11.

[18] AWM25 183/12, Pt 1 423; Brugger, pp. 107-09; Russell, pp. 197, 201.

[19] Wilson, p. 23.

[20] ‘Underlying it all is a genuine national movement of the Egyptians.’ A Note on the Present Situation in Egypt and its Causes, 19/3/1919, AWM25 183/17 423.

[21] G.O.C Instructions, 21 March 1919, AWM25 183/16.

[22] Circular Memorandum No. 26, 15 March 1919, AWM25 183/16.

[23] Report by Captain HG Palmer, AWM25 183/16

[24] Brugger, p. 116.

[25] Wilson, pp. 8-9.

[26] Report on Operation on Zagazig-Mit Ghamr Line, 23 March 1919, by Brigadier LC Wilson; Patrol Report by Lt W Lunn, 23 March 1919, AWM25 183/17.

[27] Wilson, p. 22. See also: Intelligence Summary of Australian Mounted Division, 19 March 1919, AWM25 183/16.

[28] Kim A. Wagner, ‘“Calculated to strike terror”: the Amritsar Massacre and the spectacle of colonial violence’, Past and Present, 233, 1, November 2016, pp 185-225.

[29] Wilson, pp. 24-25.

[30] Wagner.

[31] Brugger, p. 135.

[32] Brugger, p. 134, quoting a letter from Wilson to his wife.

[33] Proceedings of the court of inquiry, 11-12 April, 1919, AWM25 183/12, Part 5. See also Brugger, pp. 135-38.

[34] ‘From the 1st April till the 30 May the total number of arrests made is 518 and the total number of cases disposed of for the same period is 502. 115 arrests made in May.’ Intelligence Summary No. 54, East Delta Area 30 May, AWM25 183/16.

[35] Brugger, pp. 137-38.

[36] Hector Dinnin, Nile to Aleppo: with the Light Horse in the Middle East, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1920, p. 267.

[37] Kitchen, p. 255.

[38] House of Commons Hansard, 15 May 1919.

[39] AWM25 183/16.

[40] Personal communication.

[41] Berridge.

[42] Brugger, p. 142.

[43] Intelligence Summary, week ending 20 June 1919, AWM25 183/12.

[44] Malak Badrawi, Political Violence in Egypt 1910-1924: Secret Societies, Plots and Assassinations, Curzon, Richmond, 2000.

[45] Elie Kedourie, ‘Sa’ad Zaghlul and the British’, Albert Hourani, ed., St Antony’s Papers: Middle Eastern Affairs 2, Chatto&Windus, London, 1961, p. 157ff.

Utterly fascinating … and appalling. I had not heard of this role of Australian troops in 1919 Egypt, and I have read a considerable amount about the region. Particularly about it during the 1870 to 1941 period when Britain dominated so much of the area. There is a lot to be sad about in this account. Thanks for sharing this …