Rolf Gerritsen*

‘An essential and well-timed volume on the development of northern Australia’, Honest History, 3 September 2018

Rolf Gerritsen reviews Lyndon Megarrity’s Northern Dreams: The Politics of Northern Development in Australia

We are nearing the institutional fag end of yet another ‘wave of enthusiasm’ for northern development. So Megarrity’s book is a welcome synthesis of northern development history, particularly since World War II. We have had other good studies of northern Australia – Henry Reynolds’ North of Capricorn and Russell McGregor’s 2016 Environment Race and Nationhood in Australia: Revisiting the Empty North – but these books were around themes other than how northern development is or was organised politically. Megarrity has filled that void with this authoritative account.

Megarrity notes he was influenced by Geoffrey Bolton’s interest in creating a history of northern Australia. Bolton wrote on the Kimberleys and on North Queensland (A Thousand Miles Away) but never produced a northern synthesis. Because of Megarrity’s focus upon the actors in the continuing northern saga, this reader senses that Bolton would have approved of this volume.

Megarrity notes he was influenced by Geoffrey Bolton’s interest in creating a history of northern Australia. Bolton wrote on the Kimberleys and on North Queensland (A Thousand Miles Away) but never produced a northern synthesis. Because of Megarrity’s focus upon the actors in the continuing northern saga, this reader senses that Bolton would have approved of this volume.

Northern development has been an intermittent enthusiasm of federal governments since World War II. As Frank Bongiorno says succinctly in his introduction, it ‘has been at once a place, an idea and a problem’. That is the nub: southerners see it thus but the residents of northern Australia have a primary loyalty to their state and territory definitions of the North, invariably within their own bounds. A common North is mostly a feature of federal enthusiasms, enthusiasms recounted in this book.

Megarrity captures the essence of the southern gaze when he says that the North features ‘marginalising exoticism and otherness’ (p. 2). Of course it does. Nevertheless, the majority of the North’s population live in towns, especially in coastal Queensland, where they have suburban existences not dissimilar to those of Australians ‘down south’. Not much to see here.

Most of this book is organised chronologically rather than thematically. The first two chapters deal with the pre-1940s period. There was a northern debate then about race issues, concerns about the effect of the Chinese in the Territory and in Queensland, as well as the Kanakas in the latter. Megarrity’s is a good discussion and he reminds us of British imperial rhetoric and its hold on substantial swathes of the Australian population. The North was a place where (white) Britishers showed they could live and work in the tropics. The new Commonwealth government showed intermittent interest: it established the Institute of Tropical Medicine in 1910 in Townsville, presaging current attempts to provide a science for export to the tropical world.

World War II revealed national vulnerabilities in an empty North. Attempts were made to encourage population growth. Chifley introduced isolated residence tax breaks and the ineffectual Northern Australia Development Committee. Western Australia first petitioned for federal aid for a dam on the Ord River. The focus of northern development (opposed by Treasury and Defence) shifted to agriculture (for example, Humpty Doo) aimed at export to Asia. Megarrity makes the good point that this ‘wave of enthusiasm’ dissipated before the electorally superior nation-building attractions of the Snowy scheme.

Humpty Doo attraction 2006 (ABC/Wikimedia/Stuart Edwards)

Humpty Doo attraction 2006 (ABC/Wikimedia/Stuart Edwards)

Chapter 4 covers the 1950s and 1960s. Menzies supported urban amenities in northern towns, as well as beef roads, new bauxite/alumina industries, and agricultural research stations; his government’s contribution to northern development, especially the pastoral industry, is under-appreciated.

Later in this period, the Labor Party drove great enthusiasm for the North. Whitlam used this as part of his political agenda of national redirection and modernisation. In Rex Patterson Labor provided the only northern development federal minister in the 20th century. Labor enthusiasm was (unfortunately) helpful in goading the Commonwealth to help fund the Ord River dam. This, and the Alice Springs-Darwin railway, are two of the most under-performing investments in northern development.

A new initiative was the construction of defence facilities (Lavarack Barracks in Townsville). This was redolent of earlier fears of Asian invasion. Megarrity does not mention the synergy between that and the Vietnam War and the Liberals’ belief in the aggressive southern thrust of communism. He is, however, correct in concluding (p. 101) that northern development in the 1960s was a result of southern electoral pressures

In the 1970s, we saw real northern development, coal in the Bowen Basin and iron ore (and later natural gas) in the Pilbara. New towns were built. Ian McLean in Why Australia Prospered sees this as the only time northern economic developments were of national significance. This decade also began the 30-year conflict – at its sharpest in the Territory – between development advocates and the Land Rights movement. As Chifley was diverted by the Snowy, the Whitlam government’s interest was derailed by the cost of rebuilding Darwin after Cyclone Tracy.

Megarrity identifies three long-term trends in 20th century northern development. These are:

- Develop the north with British (currently Australian) labour. (Megarrity ignores capital investment issues.)

- Security and Asian invasion issue. This is again important currently.

- The north is ‘empty but full of promise’. This is echoed in the current strategy for infrastructure investment: the recurrent supply-side strategy ‘if you build it (the dam, the railroad) they will come’.

Now, in the 21st century, northern development has been mostly a conservative (primarily National) cause. This is for the same reason as ever since Whitlam: electoral politics.

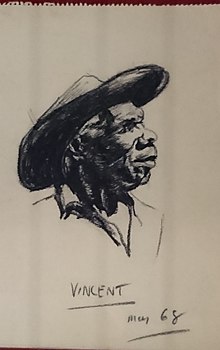

It is the reviewer’s responsibility to criticise as well as to praise. So I have minor criticisms to make of Megarrity’s treatment. The first is that Indigenous players are virtually neglected. For over 50 years, Aboriginal people were hugely important in the pastoral and pearling industries. (The latter industry does not even get a mention in the book.)

Vincent Lingiari, Aboriginal activist, drawn by Frank Hardy (Wikipedia)

Vincent Lingiari, Aboriginal activist, drawn by Frank Hardy (Wikipedia)

Secondly, Megarrity repeats common beliefs, for example, that equal pay drove Aboriginals off the stations (p. 101). This is true for the Kimberley, but less so in the Victoria River and Barkly districts of the Territory. Here, from the early sixties, road trains (travelling on Menzies’ beef roads) replaced droving and motor bikes. Then, helicopters mostly took over from horses in mustering. Northern pastoralism was mechanising only slightly later than southern agriculture. Aboriginals were being displaced before the 1966 Equal Pay Case happened. Hence the Gibb Committee-derived creation of Aboriginal living area excisions on pastoral leases in the Territory.

This book is better on Queensland and the Northern Territory than it is on Western Australia. Until the 1960s, workers in the Wyndham abattoir would come up on state ships from ‘down south’ for the killing season. This was the earliest example of the migratory or temporary (compare Fly-in/Fly-Out – FIFO) labour that is so important in northern economies today.

Historically and contemporaneously, the northern white population (except in coastal urban Queensland) has comprised what demographers call ‘escalator’ migrants, people who come to the North for opportunity and leave without planting roots. Megarrity notes the development of iron ore exports but has overlooked the role of Charles Court’s ‘take-or-pay’ natural gas contract with Woodside. In the economic development of the North that deal was huge; it eventually spawned internationally competitive Australian resource extraction companies.

These criticisms may be unfair; Megarrity is not writing an economic history. But a better knowledge of the economic development of the north would have broadened his analysis which, after all, is about northern development.

I have a couple of other disagreements with Megarrity’s approach. Both are about his methodology. First, as I said, he underplays economic issues: ‘The persistence and passion of advocates for North Australia go beyond economics’ (p. 2). This leads to some oversimplifications. Secondly, he seems not to have conducted extensive interviews, which means he misses a lot of colour that would have enhanced his story.

Let me give another economic history example. In 1900, the (South Australian) civil servants in Darwin wore clothes directly imported from Singapore, ate a substantially Asian diet and lived in a town where persons of Chinese descent outnumbered them about four to one. Now people in Darwin still wear Asian-made clothes, but these are ‘imported’ from Melbourne (even if made in China). The economic story of the North is inextricably tied up with the general development of Australia and the gradual economic subordination of the region within the national marketplace.

Megarrity has assiduously mined the conventional historian’s sources – academic scribbling, official reports, parliamentary debates and the media. This is probably because he did not have the funds to travel widely and interview the participants in recent quixotic northern dreamings. The focus on written sources means Megarrity sometimes misses local colour. For example, he quotes Prime Minister Hawke’s speech at the opening of the Burdekin Falls Dam (pp. 151-52). The speech was actually read by Peter Walsh (then Resources, later Finance Minister) who officiated at the opening. Walsh had opposed funding the dam in cabinet. So, as a fitting ‘punishment’, Hawke sent Walsh to read the speech in Hawke’s stead.

Peter Walsh (Australian Senate)

Peter Walsh (Australian Senate)

This small anecdote reveals that the Hawke government was not as serious about northern development as it pretended. Indeed, this government cancelled the shipping subsidy for goods to Darwin (having discovered that 80 per cent of the goods shipped were beer – a quintessentially northern note!) Together with Hawke not funding the promised Alice-Darwin rail link, this was one of the reasons (and not just the federal handover of Uluru to the traditional owners) which led to the Territory Chief Minister, Paul Everingham, calling an early ‘anti-Canberra’ election in December 1983.

This is a good, important, book. It is not magisterial but I suspect it will be an essential primer for decades to come. Let us hope that the current politicians playing with our money via the $5 billion Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (rightly abbreviated as NAIF) read it before we get even more supply-side field of dreams (‘build it and they will come’) northern development. The book shows that historians are relevant in contemporary policy debates. For that alone, it is to be heartily recommended.

*Rolf Gerritsen is Professorial Research Fellow, Charles Darwin University Northern Institute, based in Alice Springs. For Honest History, he reviewed Brock and Gara, ed., Colonialism and its Aftermath: A History of Aboriginal South Australia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.