‘Gallipoli Centenary Peace Campaign Talk: Petersham Town Hall, 22 April 2015’, Honest History, 12 May 2015

(Note: one of two related speeches)

1. Respect

At the outset I should say that I do not presume to tell anyone in this hall how exactly they should remember the war – that is, how their special acts of remembrance of Anzac should work when they bring to mind those who have served, suffered, or lost lives in war. It is too personal for that. Each to their own.

Many of you will have relations or friends whom you can name who served, if not in the Great War, then in more recent conflicts – or perhaps you served yourself. No special historical knowledge that I might bring to the subject can displace the personal feelings and judgments you will make about your experiences, or your losses. I respect that.

I also have members of my family who served in the Great War. Both my grandfathers served in the ‘Australian Imperial Force’ and took the oath of loyalty to the King-Emperor, George V, to ‘resist His Majesty’s enemies’, for that was the oath.

On my father’s side, Alfred Joseph Newton enlisted in October 1917, aged 31. He was married with three children. One was my father, aged just three months when Lieutenant Alf Newton left Australia. He was a dispensing chemist on transport ships to the Middle East and England, taking at least four trips in 1918 and 1919. He was Catholic, like 20 per cent of those who enlisted in the AIF.[1]

On my mother’s side, Cecil Alfred Ashcroft enlisted in February 1917. He was aged 23; like 52 per cent of the AIF he was between 18 and 24 years; like 80 per cent he was unmarried.[2] He served as a driver, in the Australian Army Service Corps, in Egypt and Palestine, at Moascar and Jericho. Suffering from malaria, he spent months in hospital at Boulac near Cairo, returned to Sydney in May 1919 and was discharged from the AIF as ‘medically unfit’ in July 1919. He was from the Protestant Establishment, son of a founder of a big butcher’s firm in Liverpool.

Anzac Day, of course, has come to mean much more than a commemoration of Gallipoli. It is a reliquary of remembrance and lamentation for all losses, in all Australia’s wars. So, naturally, all that I have to say today is watermarked with a respect for those who served. What can we say of them: from high and generous instincts, with a sense of social obligation few of us can match, men and women everywhere – on every side – exposed themselves to terrible dangers to serve militarily for causes which, to the best of their knowledge, they judged to be right. I pay tribute to those high and generous instincts.

King George V watches a parade of Australian soldiers, France, July 1917 (Australian War Memorial C00792)

King George V watches a parade of Australian soldiers, France, July 1917 (Australian War Memorial C00792)

But that respect does not mean that we throw a red, white and blue flag over everything problematic – how we get into wars; the purposes of those wars; the mistakes made in prolonging those wars. It’s a simple principle: love the warrior, hate the war; we must respect the troops, we may question and we may reject the war. We have to challenge the familiar smear: that all those who send and keep our troops abroad love, respect and honour them; and all those who question the wars to which the troops are sent hate, disrespect and dishonour them. That is contemptible political fakery.

2. The ‘Anzac spirit’

We have heard much about the ‘Anzac spirit’ this year. ‘Their spirit, our pride’, ‘Their spirit lives’ and so on. According to the sources, the original Anzacs were:

- fired by a spirit of mateship, that is, they felt themselves indissolubly bound to one another, ready to assist one another, united by a sense of solidarity for the collective – no surprise when we consider that such an overwhelming majority of the original Anzacs were working class and probably 40 per cent were trade unionists, for whom solidarity was a religion;[3]

- fiercely egalitarian and therefore contemptuous of the hierarchy that they encountered in military service, the distinctions in rank, the saluting from below, the privileges attaching to the officer class, and to the staff officers in their red tabs – and especially resentful of the officers’ prejudice against rugby league;[4]

- fiercely democratic in spirit and therefore dismissive of the old society they encountered in Britain (believing Australia was closer to the New World), critical of the social stratification, the class distinction, the aristocracy and monarchy, the inherited advantages of birth, and the vast gaps between rich and poor, the luxury amid scarcity, and the adulation of imperial baubles that they witnessed among others. We should not forget that Charles Bean, official war historian, rejected imperial honours.[5]

- And the Anzacs clearly believed in pooling their resources against common dangers.

In both world wars the Anzacs come from all political traditions. On the Burma-Thai railway were Liberals, such as Sir John Carrick, and Labor men, such as the late Tom Uren. Tom Uren left us a memorable summary of the ‘Anzac spirit’. He believed it ruled in the Hintock Road Camp on the Burma-Thailand railway under ‘Weary’ Dunlop:

“Weary” … would tax our officers and medical orderlies and the men who went out to work would be paid a small wage. We would contribute most of it into a central fund. “Weary” would then … trade … for food and drugs for our sick and needy. In our camp the strong looked after the weak; the young looked after the old; the fit looked after the sick. We collectivized a great proportion of our income.[6]

So, as the soldiers practised it, the spirit of Anzac propelled them to pool their resources, for the common good, for the common protection. Nowhere is it recorded that they divided their numbers into lifters and leaners.

Of course, there is endless fun to be had today in listening to those who present themselves as guardians of the national flame, the conservatives, the nationalists, and especially the neo-liberal, privatising, small government fanatics, and the low tax (and no tax) overpaid executives, explaining hand-on-heart that they have a special affinity with the Anzac spirit. Puff, puff, puff. They make me cry.

3. The Dimensions of the Disaster

Lest we re-romanticise the war, let me remind you of the realities of this great sprawling catastrophe of the Great War:

- Some 65 million people served in the Great War, the great majority of them conscripted.[7]

- The estimates of the total numbers killed vary widely, depending on where you draw the line, in time and geography, and whether you count the civil wars that exploded in the aftermath of the war, in Eastern Europe, Turkey and the Middle East. A common total for 1914-18 is 17.8 million people.[8]

- The reach of the war was breath-taking. Britain ‘recruited’ (or conscripted) over a million African ‘carriers’ during the fighting. Ninety-five thousand of these died from all causes including malnutrition, overwork, and disease, almost more than the war dead of Australia and Canada combined.[9]

- For Australia, a country of less than five million, over 300 000 served overseas, 62 300 were killed (including 550 who died by their own hand in 1919-20). Another 8000 died a premature death in the years that followed.

- Among the Anzacs abroad there were 208 000 wartime hospitalisations due to wounding, 30 per cent of these due to shell shock. Of the survivors, the 270 000 who returned home, more than half were discharged as medically unfit. Of the 62 000 killed, it is estimated 23 000 were missing, pulverised, no known grave.[10] As Marina Larsson, author of Shattered Anzacs, estimates, for every ten soldiers sent abroad, two were killed outright and three were returned with pensionable disabilities. Thus, 90 000 were disabled and by 1939 there were still 77 000 men from the AIF living with a war disability, with an average of three dying per day of war-related injuries.[11]

- The cost to Australia was staggering. The nation spent £350-370 million on the war, 70 per cent of it borrowed, for there was no excess profits tax in Australia. To put this into perspective, the last peacetime Commonwealth budget of 1913-14 showed total outlays of only £24 million (one-third of which was spent on defence). So, in four years of war, the war gobbled up the equivalent of the total of 15 Commonwealth budgets.[12]

- As we are marking the Gallipoli centenary in a few days, we should pause to consider the battle-deaths in that campaign[13]:

- Turkey: 86 700

- Britain: 26 054

- France: 9787

- Australia: 8709

- New Zealand: 2721

- India: 1682

- Newfoundland: 49.

Australian and Turkish dead, Gallipoli, 24 May 1915 (Australian War Memorial H03955)

Australian and Turkish dead, Gallipoli, 24 May 1915 (Australian War Memorial H03955)

As the unforgettable Irish folk-song put it long, long ago, ‘every tear would turn a mill’ for ‘Johnny has gone for a soldier’.

Some will respond, ‘Yes’, but in spite of all, the war was a ‘dire necessity’, a ‘tragic necessity’, to repel the ‘German peril’, and there was ‘no alternative’. The truth is that the war arose out of the era of New Imperialism and the Old Diplomacy – from systemic faults shared by all the great powers. The plague was on all houses. Such a bloodletting as 1914-18 could only be justified to avert an appalling evil or to achieve an imperishable gigantic good. The reality is that all sides shared in the systemic evils that produced and prolonged the war: all sides planned for colonial seizures; all sides lapsed into authoritarianism; all sides plotted to close down their commercial competitors; all sides indulged in atrocity – remember that 760 000 German civilians died as a result of the starvation blockade which was prolonged after the armistice.[14]

Some people imagine that the British Empire fought in 1914-18 for democracy. Remember the Empire was formally allied, for 32 months of a 51 month war, to Tsarist Russia, Europe’s most ruthless despotism. But did Australia fight for democracy? Keith Murdoch, great propagandist in command of the United Cable Service controlling all war news reaching Australia, was more realistic. He told General Pompey Elliott in May 1918, ‘I admit that democracy must be cast aside by all patriotic men if the labouring classes become selfish and indolent under the authority it gives them’.[15]

And when it was all over in 1918, and Germany turned around and established a liberal-socialist republic, the victors would not negotiate, democracy in Germany was not consolidated, there was no self-determination for colonial peoples, the empires of Britain and France were hugely engorged, and the great fantasy balloon was inflated that Germany could pay everyone’s war debts – every last dustman in Berlin and his grandchildren – so there need be no wealth taxes among the victors.

War is the pasture of bigots; war is the solvent of civil liberty; whichever side won the war, war was the victor.

Commemoration – or disremembering?

Is our commemoration at risk of descending into a national festival of self-congratulation? Are we seizing upon feel-good history – and disremembering everything difficult?

In September 1915, while on the Gallipoli peninsula itself, Charles Bean, Australia’s war correspondent, wrote in his personal diary of the danger of history descending into mere flattery. He had observed instances of Australian gallantry and instances of Australian fear and flight. He wanted to write about both. But, he confessed in his diary, ‘the probability is that if I were to put it into print tomorrow the tender Australian public, which only tolerates flattery and that in its cheapest form, would howl me out of existence’.[16]

There is a challenge to us. Are we better than lapping up mere flattery?

Australia’s plans for the centenary of the Great War began in 2010. A ‘National Commission on the Commemoration of the Anzac Centenary’ was set up – ‘Anzac’ rather than the Great War itself. This was unfortunate. It encouraged an inward-looking nationalist tone, rather than our looking out and facing up to big questions arising from such an international catastrophe. The dangers of ‘big-noting’ and the ‘small-nation syndrome’ loomed. (Imagine if the British had inaugurated a British Expeditionary Force Centenary, or the Americans a ‘Doughboys’ Centenary). Still, the commission submitted a valuable report entitled How Australia may Commemorate the Anzac Centenary. It included this memorable recommendation:

The most bitter disappointment for the original Anzacs was that their war was not, in fact, the “war to end all wars”. The best way we can honour their memory is to focus our thoughts on how we might reduce the risk that future Australians will have to endure what they have endured. (p. 28)

So right from the beginning there was the hope: the centenary moment ought not be just a chance to peddle a ‘see-how-great-we-are’ story, not just a moment for a flood of books and exhibitions that puff military achievement. And there are scores of thoughtful events, exhibitions and TV programs, reminding Australians of the cost of war.

But sometimes the tone – especially in politicians’ major addresses, on Anzac Day, Remembrance Day, and Albany Day – caters for that strange schizoid Australian conviction: that war is a bad thing; but the fact that we are very good at it is a very good thing. Sometimes it is worse. Sometimes politicians and others structure their speeches this way: first, they catalogue the fabulous things our military achieved and suggest we were indispensable to victory; secondly, they catalogue the fabulous things the war did for our nation – it put us on the world stage, made us conscious of our nationhood for the first time, it was the crucible of national identity, the ‘baptism of fire’, the ‘test of our mettle’ and so on; thirdly, they then suggest, as convincingly as they can – not easy – that the last thing they wish to do is to glorify war.

The hyperbole can be wince-making. At the Anzac Day national ceremony last year our Prime Minister set out to flatter his listeners, as the sons and daughters of Anzacs. Tributes and praise flowed freely toward all. As a man who had not fought himself, he self-effacingly explained, he expressed his ‘awe’ for ‘the ANZAC generation’. The soldiers were ‘our mighty forbears’. Then, deploying the universal cliché, the PM explained that war ‘can bring out the best in us’. There followed some grand claims. Our achievements, he said, quoting the famous Charles Bean, were to ‘flash across the world’s consciousness like a shooting star’. As Bean had put it, the Anzacs’ heroism established ‘a tradition that may work for centuries’ and forged ‘qualities always vital to the human race’. Still quoting Bean, the PM asserted that in the Great War Australia’s name began to ‘rise high in the esteem of the world’s oldest and greatest nations’. Indeed, Australia ‘came to know itself’. It was ‘Australia’s moment on the stage of history.’[17]

Charles and Effie Bean, Tuggeranong, FCT, 1920-25 (Australian War Memorial P02751.350)

Charles and Effie Bean, Tuggeranong, FCT, 1920-25 (Australian War Memorial P02751.350)

What do we misremember?

Perspective

We should keep our contribution to the war in perspective. A Division in the army is roughly 20 000 men. In 1914, we sent one division, the 1st Australian Division, and we topped up the ‘New Zealand and Australian Division’, both thrown into the conflict at Gallipoli. In August 1914, the European powers mobilised:

Germany: 96 divisions (eventually 251 divisions raised)

Austria-Hungary: 48

Russia: 114

France: 82

Britain: 6 (eventually 75 divisions raised)

Australia: 1 (eventually 5 divisions raised).[18]

Purposes

We should not lose sight of the purposes of battle. In this centenary, we should surely be conscious of the imperial deals underpinning battle, in both the Middle East and Europe, but they are almost completely ignored. Just a small sample would include:

- the Straits Agreement of March 1915, the agreement to give the Dardanelles and Constantinople to Russia;

- the Treaty of London, April 1915, under which Italy gained territory that is now Croatia and a share in the carving-up of Turkey;

- the Sykes-Picot Agreement, May 1916, under which Britain and France agreed upon carving up the whole of the Middle East, from Palestine to Iraq;

- the Paris economic resolutions, June 1916, under which plans were made for a post-war economic boycott of Germany;

- the Bucharest Convention, August 1916, under which Romania was bribed into the war with a promise of a great slice of Hungary;

- the Franco-Russian Agreements, February 1917, under which France turned a blind eye to Russian annexations in Eastern Europe and Russia a blind eye to French plans to take the Rhineland; and

- the St Jean de Maurienne Agreements, April 1917 – complementing Sykes-Picot, under which Italy gained a share in the carving up of the Ottoman Empire.

Australians were still fighting into a fourth year of war in 1918 because of this escalation of war aims, almost all of it secret from the people doing the fighting.

Division

Because our politicians and newspapers wish to flatter us, the universal cliché deployed is that Australians are ‘at their best in war’, as a truly exceptional people. The truth is that, like most nations at war, Australians began to quarrel with each other over the purposes of the war. ‘Are our hands clean?’, many asked. ‘Are we fighting for imperial aggrandisement?’ And the name-calling began, ‘Traitor!’ and ‘Warmonger!’, and we began to scratch each other’s eyes out.

What was truly exceptional was that twice, in October 1916 and again in December 1917, the Australian people were asked if they wished to give a blank cheque to the government and the generals to press as many men as they wished into the mechanied killing – and twice the people said ‘NO’. This was achieved, against the advice of the newspapers and against a government misusing its emergency powers to shut down debate. There were huge demonstrations and show trials of dissidents. It was all exceptionally bitter.

Lost opportunities for a negotiated peace

Sadly, it looks as if all the centenary dates we are going to mark in Australia are the dates of battles, from the sinking of the Emden, to Gallipoli, to Fromelles, Pozieres, Passchendaele, Villers-Bretonneux and so on. The truly historic moments in this titanic struggle – when the people pressed for an end to the bloodshed and when the politicians and diplomats turned aside many promising opportunities for a negotiated peace – are going to be ignored.

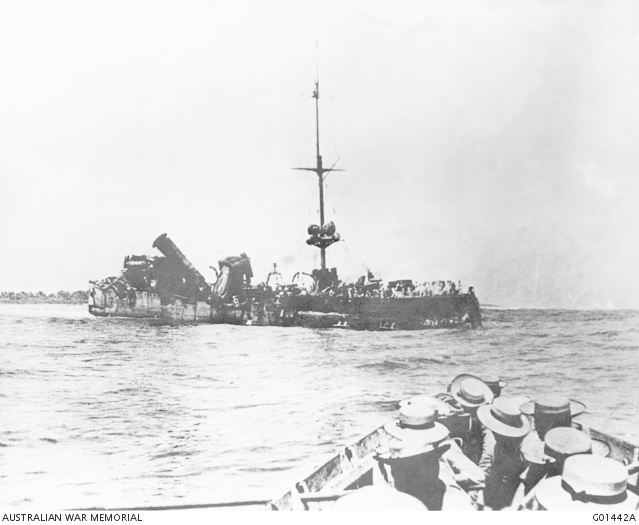

A lifeboat from HMAS Sydney on its way to the Emden, 11 November 1914 (Australian War Memorial GO1442A)

A lifeboat from HMAS Sydney on its way to the Emden, 11 November 1914 (Australian War Memorial GO1442A)

After the $400m is spent supposedly ‘educating’ the Australian people on the war, will the great international forces pushing for a negotiated end to the war be still unknown to most Australians? These are just a few:

- the International Congress of Women, The Hague, April 1915;

- the German and American Peace Notes, December 1916;

- the first Russian revolution and the proposal for an Inter-Allied Conference, to revise war aims, May 1917;

- the Reichstag Peace Resolution, July 1917;

- the proposed Stockholm Socialist Conference, June-August 1917;

- the Papal Peace Note, August 1917;

- the ‘Lansdowne Peace Letter’, November 1917;

- the second Russian Revolution of November 1917; and

- the Swedish Archbishop Nathan Söderblom’s proposal for an International Christian conference to negotiate a compromise settlement, February 1918.

5. Hard Truths – the Great War

Let us consider just a few of the realities of this war, in which our ‘Australian Commonwealth Military Forces’ were transformed into the ‘Australian Imperial Force’. We should not forget that we were hitching our wagon to the vast British imperial project, that vacation-land for protectionists, cheap labour scammers, rent-seekers, and all those seeking to escape the factory acts and trade unions at home, and to socialise their costs and privatise their profits under the umbrella of Empire.

- Australia planned for imperial expeditions and colonial seizures before 1914. This was done even though, as the Inspector of Overseas Forces, the British General Sir Ian Hamilton, visiting Australia, advised British Prime Minister Asquith on 14 April 1914: ‘I came out here to urge … some small section of their army earmarked, in peace, for expeditionary imperial service … [But] the whole vital force of the country, i.e. the rank and file of its people, are standing firm against any such proposition.’[19]

- Australia’s government sent a cable offering an expeditionary force of 20 000 men on Monday 3 August, 40 hours in real time before Britain had decided to declare war on Germany – when Britain’s decision hung in the balance. We boosted the cause of those pushing for instant war.

- Atrocities then occurred on every front, daily: atrocities deriving from the everyday industrialised killing, the mechanised slaughter, the killing of prisoners, the U-boat war, the starvation blockade; atrocities such as the killing of civilians in Ireland and Belgium in the West, and of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire; and atrocities on the part of our Tsarist Russian ally, the ‘pogroms’ – the deportations, killings and robbery of Jewish communities – behind Russian lines in Galicia.[20] As Arthur Wheen, Australian translator of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, put it, the British imagined they were ‘saints at war’ when the reality was ‘the bestiality was wherever the war was’.[21]

- Not everything done by the anti-German coalition was blessed with moral clarity. Australia’s efforts were part of great imperial projects – to carve up territory and resources in the Middle East, Africa, China and the Pacific, to throttle German commerce, and to enlarge the British Empire.

- We honour the Anzacs in death. But did Australia look after its Anzacs in life? Did we carefully weigh objectives and costs? Did we demand consultation on the big issues? No. Australia achieved no significant role in the high diplomacy of the war. We left it to London.

- What kind of men in London were given Australian soldiers’ lives, in trust, by our government? For example, it was Lord Curzon, in Asquith’s Cabinet, who advised the Cabinet in July 1915 that the war was now a simple matter of killing Germans. He concluded: ‘If then two million (or whatever the figure) more of Germans have to be killed, at least a corresponding number of allied soldiers will have to be sacrificed to effect that object’.[22] It was also Lord Curzon, a key member of Lloyd George’s War Cabinet in 1917 – the Cabinet that failed to halt the disastrous third battle of Ypres – who was reputed to have remarked, upon seeing men bathing on the Western Front, ‘Dear me! I had no conception that the lower classes had such white skins’.[23]

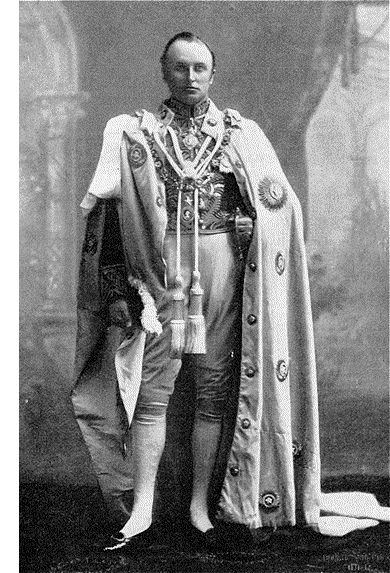

Lord Curzon 1905 (Wikimedia Commons)

Lord Curzon 1905 (Wikimedia Commons)

6. Hard Truths about Australia’s Gallipoli

The men who enlisted to join the AIF all expected to go to Britain and to fight to save Belgium. But they were just getting their sea-legs in the first week of November 1914 when the war exploded into the Middle East, as Britain and France loyally followed Russia into war against Turkey. And the force was stopped in Egypt, which had just been annexed outright by Britain, along with Cyprus. The men of the AIF were diverted, first to keep restless Egypt secure, and then on to Gallipoli. The Greek island of Lemnos was the staging point; it had been occupied by the British in February, flouting Greek neutrality.

The real central point of Australia’s Gallipoli is not ‘how did we fight?’ but rather such questions as ‘why did we fight?’ and ‘what did we fight for?’ We have to face hard realities about the diplomatic deals underpinning the campaign. Was it really a moment of national awakening? Or was it a moment of our willing imperial subservience? Was it a triumph of the national spirit or a triumph of the colonial spirit over our national spirit, which led our leaders to despatch our forces so recklessly?

The campaign arose from British efforts to keep Russia in the war – by winning, for the Tsarist despotism of Nicholas II, its most cherished war aim, Constantinople and the Straits. The deals were done at Albert Gate House, the French Embassy in London, Chesham House, the Russian Embassy in London, and at the Foreign Office in Whitehall, with negotiations beginning in November 1914.

Was Australia involved in these deals? Not in the least. For some weeks in late 1914 Prime Minister Andrew Fisher had pressed for an Imperial Conference to be held in 1915, so that Australia might have some say in the high diplomacy of war. Britain said no. Fisher then wrote to Lewis Harcourt, the Colonial Secretary in London, saying that he would not press his views. ‘We have a policy for this trouble that gets over all difficulties. When the King’s business will not fit in with our ideas, we do not press them’.[24] Such a low bow! Harcourt was thrilled, and quoted this, to great cheers, in the House of Commons, just a fortnight before Australians began to die at Gallipoli.[25]

Meanwhile, the deals vital to the Gallipoli campaign were done in negotiations spurred on by George V and Nicholas II of Russia. The key diplomats were Sir Edward Grey and Sergei Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister, and Paul Cambon and Alexander Benckendorff, the French and Russian ambassadors in London, and George Buchanan and Maurice Paléologue, the British and French ambassadors in St Petersburg.

Eventually, diplomatic deals were struck: the secret Straits Agreement of 8-12 March 1915 and the secret Treaty of London, signed 26 April 1915. The first treaty bribed Russia to stay in the war; the second bribed Italy to enter the war. Hovering in the background were the rival corporate interests – Royal Dutch Shell, Anglo-Persian Oil, and Standard Oil – looking for the reopening of the Straits, a British and French partition of the Middle East, and a market share in fuelling the war.[26]

So Australians would soon die at Gallipoli, mostly for people they had never heard of and for deals hidden from them. For example, little did the Catholic soldiers of the AIF, digging in at Gallipoli, know that, under article 15 of the Treaty of London, signed 26 April, Britain, France, Russia and Italy ‘pledge[d] themselves’ to cooperate in ‘not allowing’ the Catholic Pope Benedict XV ‘to undertake any diplomatic steps having for their object the conclusion of peace or the settlement of questions connected with the present war.’[27]

Such were the territorial carve-ups and secret bargains at the heart of the campaign. And yet, the eccentric monarchs, reckless diplomats and duplicitous politicians connected with launching the Gallipoli campaign are virtually unknown in Australia, a century later.

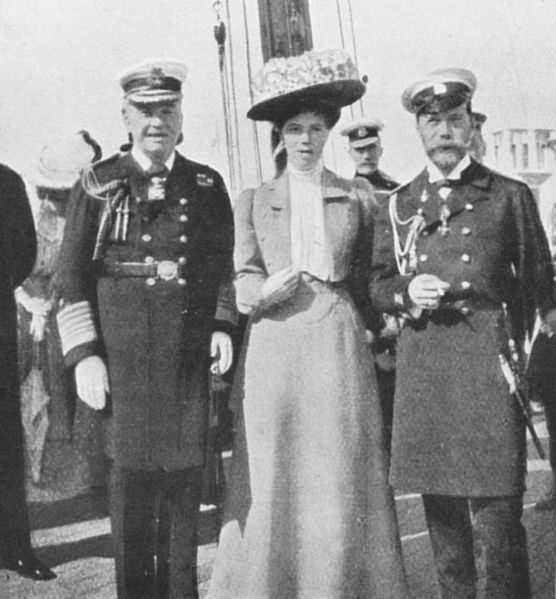

Admiral Lord Fisher, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Czar Nicholas, 1909 (Wikimedia Commons)

Admiral Lord Fisher, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Czar Nicholas, 1909 (Wikimedia Commons)

Was the diplomacy important? Admiral Fisher, who had to cooperate with Churchill in planning the campaign, was very pessimistic about the chances. As he wrote to Admiral Jellicoe on 27 February 1915, ‘It is all Foreign Office business and pressure from Russia and France. We are their facile dupes.’[28] And who was to profit from the battle if Australians had triumphed and made it to Constantinople? As Sir Edward Grey told Buchanan, Britain’s Ambassador in St Petersburg, on 11 March 1915: ‘Tell the Russians “The direct fruits of these operations will, if the war is successful, be gathered entirely by Russia”’. [29]

But we are not the victims here of a British plot. Australia was willingly subservient. The Australian government, custodian of Australian lives and treasure, did not ask for more light. Our government was hell-bent on unqualified loyalty, in the hope that Britain would bail out Australia from the threat of Asian invasion into the future. Thus, they had set up the nation to be taken for granted. For example:

- The birth of Anzac Day was a conscious effort to expunge the memory of disaster, to console the grieving, and to maintain recruiting in the face of the defeat at such enormous cost. The Anzac Day Commemoration Committee, founded in Brisbane at the beginning of 1916, made this clear.

- Prime Minister Hughes, in his first week in office in late October 1915, was asked in parliament if further commitments to the Gallipoli campaign were not futile. He answered: ‘Our business is to carry out the instructions of the Imperial Government … I do not pretend to understand the situation in the Dardanelles, but I know what the duty of this government is; and that is – to mind its own business, to provide that quota of men which the Imperial Government think necessary in the circumstances … That we shall do.’[30]

- The Australian people’s view of the Gallipoli campaign was rooted in ignorance of its purposes. Both the Straits Agreement and the Treaty of London, the diplomatic deals undergirding it, were never revealed to them until after the Russian Revolution of November 1917; and even then the censorship hushed up knowledge.

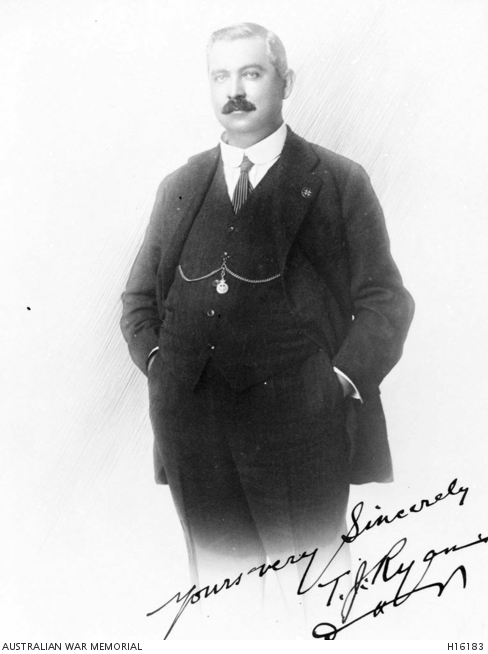

- Australian politicians kept mouthing the most trite and naive things. For example, Premier TJ Ryan of Queensland, in January 1916, at a meeting urging the foundation of the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee in Brisbane, reminded his hearers ‘that Britain sought no territorial aggrandisement’ in this war – but he hoped the Gallipoli peninsula would pass into British hands.[31]

- Joseph Cook. then Minister for the Navy, in his diary, 18 January 1917: ‘We fight for [the] rights of nationalities and not for territorial aggression. We ask for nothing for ourselves.’[32]

Should we approach the centenary of Anzac in such a mist of naiveté, sprinkling platitudes suitable for primary school? Should Anzac be the place where adult good sense goes to die?

Or do we ask hard questions? Did Anzac define our nation? Or did it diminish our nation?

7. Lessons of the Great War and Gallipoli

What then are the real lessons of the Great War and Gallipoli?

- That deterrents can fail to deter.

- That accidents can happen – when the Old Diplomacy seeks to manage the New Imperialism, or the nuclear balance today.

- That competition for Empire and commercial supremacy can land all in a bloodbath.

- That a world with weak international institutions and laws, with all nations armed to the teeth, and all jealously guarding their rights to take unilateral or preemptive action, is a hellishly dangerous world.

- That great corporate vested interests, in empire and war, can cloak those interests in the garb of the national interest. This vast imperial war was a vultures’ frenzy.

- That sordid causes can be smuggled into noble ones once wars are under way.

- That the resort to war marks a failure of diplomacy and international law – and such international institutions and law as we have can only be as strong as the Great Powers allow.

- That nothing is more dangerous to peace than the conviction that someone else must do something to save it.

- That the inner executive can triumph over parliament and people when the ‘war powers’ are unreformed, with no requirement to appeal to parliament before forces are deployed abroad.

- That the passing generation, with its property secure and its careers established, is always tempted to betray the interests of the rising generation – and place the chief burdens of war upon that generation.

- That those who choose to sacrifice the young then create a cult of the fallen – and praise those they sacrificed for their self-sacrifice.

- That war is the pasture of bigots.

- That war will always dissolve civil liberties.

- That nations going to war are very like each other – fearful, reckless, high-handed, undemocratic, easily spooked.

- That nations engaging in war are very like each other – intolerant, cruel, and inclined to argue that all law must bend before desperate necessity.

- That in war, almost always, nations are at their worst. Fearing the enemy at the gate, they search frantically for the enemy within.

- That those who offer principled opposition to war will experience the grand simplifiers’ rhetorical slither, and have their patriotism impugned – ‘you understand the enemy, you sympathise with the enemy, you are an apologist for the enemy, you are an agent of the enemy’.

- That slavish loyalty to Alliances can mean slavish loyalty to the misjudgements of others.

TJ Ryan, premier of Queensland during the Great War (Australian War Memorial H16183)

TJ Ryan, premier of Queensland during the Great War (Australian War Memorial H16183)

The words of Kemal Ataturk – leaving aside questions over their true origin, and the dubious suggestion that the Anzac mothers ‘sent’ their sons to Gallipoli – have achieved great resonance because they evoke reconciliation. Is there no such statement from Australia to be had in 2015? Will no one say for us, standing on the beach at Anzac Cove, something seamed through with sanity? Something like: ‘What comes of Empire! What comes of Empire! We regret, and we lament, with all our hearts, that our forebears, on each and every side, so recklessly launched a great episode of industrialised killing here, and robbed so many young men of their futures, and plunged their families into incalculable grief – on each and every side. But they lie together now, in their common humanity, and we reflect, in our common sadness, upon our common humanity – with infinite regret.’

8. Prospects for Peace

The dogma of deterrence still has a tenacious grip on the heart of the world. Naturally, every people reserves to itself the right of self-defence; there is no national act of conscientious objection to all violence.

But in every nation there is a competition between two cultures: one that normalises and valorises war, fatalistically accepts that war has a great future in the twenty-first century, and looks to national greatness achieved in wars fought in the past; and another culture that laments every war as a return to medievalism and barbarism, that strives again and again for diplomatic solutions ahead of the solutions that dynamite and cordite promise, that finds warfare utterly and irredeemably repellent, that chooses war by democratic means, only as a very last resort, and only when it is absolutely in self-defence. Which culture is being encouraged by our centenary?

On the instinct of self-defence to be found in every people is built the dogma of deterrence, the self-delusional conviction that our security is guaranteed by our ability to scare all our enemies straight. It rests on two terrible twins:

- faith in armed preparedness to a point of almighty unmatched force – forever renewed, forever upgraded, to the enrichment of fragments of the economy and the impoverishment of most of it;

- faith in tighter and tighter regional military alliances with the like-minded – rather than faith in wider multilateral engagements, collective security, stronger international institutions and international law.

Such is the power of this doctrine that when matchless military power and tight alliances fail to deter war, or fail to create a durable peace, some people argue that it follows as the night the day that there mustn’t have been enough weapons, or alliances were too loose, or there simply wasn’t enough war.

The alternative to this murderous circular reasoning, based on fear, has been slow in the making: the internationalist vision, based on an acceptance of the international arbitration of disputes as more just and sensible than every nation being the arbiter of the justice of its own cause – with a dagger in its teeth. Little pieces of that international vision have been only slowly realized here on our spinning planet over the last one hundred years: laws of war at The Hague Peace Conference in 1899; the establishment of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague Conference in 1907; the League of Nations established at Geneva in 1919; the United Nations inaugurated at the San Francisco conference in 1945; the march of international cooperation to be seen in such institutions as the European Union or the International Criminal Court.

In peaceful Western Europe today lies a simple lesson: is the nightmare of an invasion for France, from her powerful German neighbour, now at an end because of France’s unmatched armed preparedness? Or is it because of the growth of the international spirit and of international institutions on the European Continent? Security on such a basis is real.

The great truth remains the same: that if we want freedom from war, an end to the Armageddon that still hangs over us in the nuclear balance, it is the same old internationalist project, unrealised still, that we must rededicate ourselves to realise: to instill a passionate hatred of war and a passionate desire to recognise the universality of the brotherhood and sisterhood of man, so that there is popular and political will to complete the great project of the twentieth century: to move from a faith in unilateral security through matchless power, and from bilateral and trilateral and regional security pacts, to a multilateral collective security, based on solid foundations of international law.

Do we in Australia promote that – or sneer at that?

This was the vision weakened by the great powers’ decision to leave arbitration as optional when the World Court was created in 1907; the vision hobbled by the imperial settlement of 1919; the vision hobbled again by the resumption of a bipolar competition between groups of powers in the Cold War era after 1945; the vision hobbled in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 by the rebuffing of Russian feelers seeking Russia’s inclusion in Europe, and by the building of ‘buffer’ security arrangements instead.

In conclusion, let me quote Brigadier Chris Roberts, Vietnam Vet and former SAS commander, and author of a new study of the Anzac landing. He lost his great-uncle who died at The Nek in 1915: ‘Oh yeah, we have a photo of him … I mean when I first visited Gallipoli I actually sat in the trench that he went from, and I thought a lot about him. He was a fine young man. He was 24, he’d just turned 24. And when you look at him, he’s a strapping handsome young man. And you say, what a waste! What a waste! And you know, if there is anything that we should take away from our commemoration of the Great War is the waste of going to war.’ [33]

Little Digger Collectables: Australian Lighthorse, The Nek, Gallipoli 1915, $29.99, ‘painted metal figurine measures approximately 5.4 cm. Suitable for collectors 14 years +’ (Australian War Memorial shop)

Little Digger Collectables: Australian Lighthorse, The Nek, Gallipoli 1915, $29.99, ‘painted metal figurine measures approximately 5.4 cm. Suitable for collectors 14 years +’ (Australian War Memorial shop)

So, let us honour the Anzacs, past, present and future, in life – not simply with a cult of the fallen, a cult of death.

As we reflect on the centenary of Gallipoli, let us ask hard questions: should the centenary be used to boost our history of expeditionary warfare, far from Australia’s shores, and to vindicate contemporary commitments to war? Should we be spending up big on what may descend into a mere nationalist jamboree, if we are neglecting the health, and especially the mental health needs, of returning veterans from our contemporary commitments?

As the World War II poet put it:

Do not despair

For Johnny-head-in-air;

He sleeps as sound

As Johnny underground.

Fetch out no shroud

For Johnny-in-the-cloud;

And keep your tears

For him in after years.

Better by far

For Johnny-the-bright-star,

To keep your head,

And see his children fed.[34]

___________________________________

[1] Robert Bollard, ‘Economic conscription and Irish discontent: the possible resolution of a conundrum’, in Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber, ed., Fighting Against War: Peace Activism in the Twentieth Century (Melbourne, 2015), p. 141.

[2] Marina Larsson, Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War (Sydney, 2009), p. 31.

[3] LL Robson, ‘The Origin and Character of the First A. I. F., 1914-1918: Some Statistical Evidence’, Historical Studies, 15, 61 (October, 1973), p. 738, Peter Stanley, Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force (Millers Point, 2009), ‘Part Two, 1915, Novices’, and Frank Bongiorno, Rae Frances and Bruce Scates, ed. Labour and the Great War (Sydney, 2014), ‘Preface: Labour History at War’, p. 3.

[4] Richard Noonan, ‘Offside: rugby league, the Great War and Australian patriotism’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 26, 15 (2009), pp. 2201-2218.

[5] Ross Coulthart, Charles Bean (Sydney, 2014), p. 379.

[6] Tom Uren, address to the South Coast Branch of Union Aid Abroad, https://chriswhiteonline.org/2015/01/vale-tom-uren .

[7] John Connor, unpublished paper, ‘Why was it easier to introduce conscription in some English-speaking countries than in others?’, Conscription Conflict and the First World War Seminar, Melbourne, 8-9 April 2015, p. 1.

[8] Ruth Leger Sivard, World Military and Social Expenditures 1987/88 (Washington, 1987), pp. 29-31, quoted in John Mueller, ‘Changing attitudes towards war: the impact of the First World War’, British Journal of Political Science, 21, 1 (1991), pp. 1-28.

[9] Edward Paice, Tip and Run (London, 2006), p. 392. Cited by E. Johns and Gabriel Carlyle, The World is My Country (London, 2015), p. 79.

[10] Australian statistics are taken from David Noonan, ‘Why our WWI casualty numbers are wrong’, Sydney Morning Herald, 28 April 2014 (https://www.smh.com.au/national/ww1/why-our-wwi-casualty-number-are-wrong-20140430-zr0v5.html) and see David Noonan, Those We Forget: Recounting Australian Casualties of the First World War (Melbourne, 2014), p. 196 and see Chapter 7, ‘Some Comparisons in this Global War’.

[11] Marina Larsson, Shattered Anzacs, pp. 18-19.

[12] ‘The federal Budget’, The West Australian, 6 October 1913, and https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1415/AustToWar1914 .

[13] Australian War Memorial, First World War gallery. For different figures, and a total of Allied casualties of 390 000, see Robin Prior, Gallipoli: The End of the Myth (Sydney, 2009), p. 242.

[14] C. Paul Vincent, The Politics of Hunger: The Allied Blockade of Germany, 1915-1919 (Athens, Ohio, 1985), p. 170.

[15] Murdoch to HE Elliott, 9 May 1918, Murdoch Papers, MS 2823/34, quoted in Douglas Newton, British Policy and the Weimar Republic, 1918-1919 (Oxford, 1997), p. 125.

[16] CEW Bean, entry for 26 September 1915, in ‘Official History, 1914-18 War: records of C. E. W. Bean, official historian papers’, AWM38 3DRL 606/17/1 (Australian War Memorial).

[17] https://www.pm.gov.au/media/2014-04-25/address-anzac-day-national-ceremony-canberra .

[18] Norman Stone, The Eastern Front, 1914-1917 (London, 1998), p. 40; Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig, ed., War Planning 1914 (Cambridge, 2010), 34, 39, 147, 232, and 234, and Holger Herwig, The Marne, 1914 (New York, 2009) p. 61.

[19] General Ian Hamilton to Asquith, 14 April 1914, Hamilton Papers, 5/1/87 (Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives), quoted in John Mordike, ‘We Should Do This Thing Quietly’ (Canberra, 2002), p. 90.

[20] Alexander Prusin, ‘The Russian military and the Jews in Galicia, 1914-15, in Eric Lohr and Marshall Poe, ed., The Military and Society in Russia, 1450-1917 (Boston, 2002), pp. 525-544.

[21] Arthur Wheen to Miss Lewers, 18 April 1929, in Tanya Crothers, ed., We Talked of Other Things: The Life and Letters of Arthur Wheen, 1897-1971 (Woollahra, 2012), p. 185

[22] Lord Curzon, ‘Registration and military service’, 21 June 1915, CAB 37/130/19 quoted in David French, ‘The meaning of attrition, 1914-1916’, English Historical Review, 103 (April, 1988), p. 398.

[23] Quoted in Harold Nicolson, Curzon: the Last Phase (London, 1934), p. 48.

[24] Fisher to Harcourt, 15 February 1915, read to the House of Commons, Parliamentary Debates, Commons, 5th series, Vol 71, p. 16 (14 April 1915).

[25] Harcourt wrote back to the Governor General on 15 February 1915: ‘I received a charming letter yesterday from Fisher saying that he would not press for the Imperial Conference against our opinion … and adding that there was an easy cure for these matters because, when their (Australian) opinion did not fit in with the King’s business, they did not press their views’. See Harcourt to Munro Ferguson, 27 March 1915, MS Harcourt 479 (Bodleian Library).

[26] Gregory Patrick Nowell, Mercantile States and the World Oil Cartel, 1900-1939 (Ithaca, 1994), Ch. 3, ‘The Great War and the struggle for commercial advantage’.

[27] ‘The Treaty with Italy, 26 April 1915’ reproduced in F. Seymour Cocks, The Secret Treaties and Understandings (London, 1918), p. 40

[28] Fisher to Jellicoe, 27 February 1915, quoted in Nicholas Lambert, Planning Armageddon (Cambridge, Mass., 2012), p.320.

[29] Grey to Buchanan, 11 March 1915, quoted in CJ Lowe, ‘Britain and Italian Intervention, 1914-1915’, Historical Journal, 12, 3 (1969), p. 544.

[30] William Morris Hughes, Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, Friday 29 October 1915. I am grateful to Dimity Torbett for this reference.

[31] See ‘Honouring the brave’, Brisbane Courier, 11 January 1916, p. 8.

[32] Joseph Cook Diary for 1917, 18 January 1917, Cook Papers, National Archives of Australia, M3580, 9. I am grateful to Dr Greg Lockhart for this reference.

[33] Chris Roberts, on ABC Radio 666 Canberra ‘Capital constitutional’, interview with Alex Sloan – Brigadier Chris Roberts, Monday 16 March 2015.

[34] ‘For Johnny’, by John Pudney.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.