Australia’s Vietnam War – and keeping it in context: others in the series

_____________________________

Parades, recognition and misremembering

Part of the narrative of Australia’s Vietnam War in the more than 40 years since our commitment ended has been that Australian soldiers returning from their deployments were badly treated by their fellow Australians. Australian prime ministers from Hawke to Abbott have spoken in general terms about this. Prime Minister Hawke in 1988 spoke of ‘the recognition at last extended to our Vietnam veterans’ at the welcome home march in October the previous year.

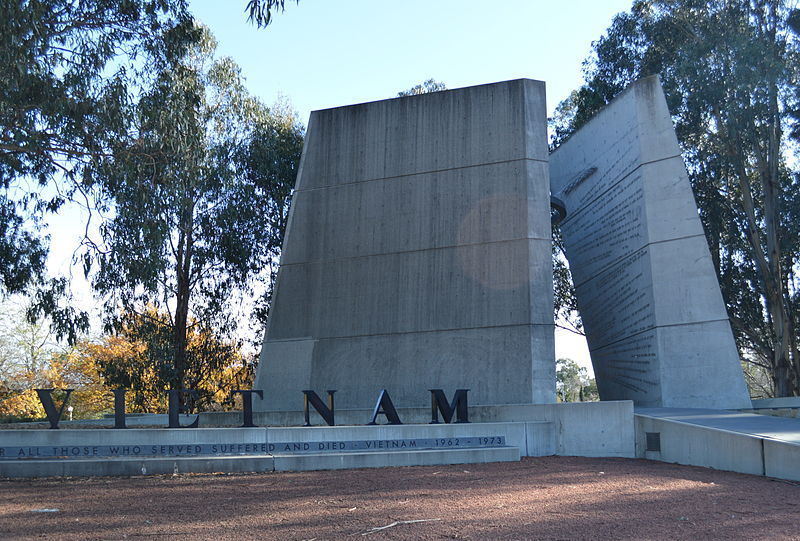

Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Anzac Parade, Canberra (Wikimedia Commons)

Australian Vietnam Forces National Memorial, Anzac Parade, Canberra (Wikimedia Commons)

Prime Minister Howard, nearly two decades later, spoke of our ‘our nation’s collective failure at the time to adequately honour the service of those who went to Vietnam. The sad fact is that those who served in Vietnam were not welcomed back as they should have been.’ Prime Minister Abbott, speaking in 2015 at a welcome home parade for soldiers returning from Afghanistan, said, ‘Now, some decades ago, Australians returned home from another war and were not properly acknowledged’.

Ministers like Senator Michael Ronaldson (2013-15) have spoken in similar terms, Ronaldson saying, for example, in May 2015:

We honour our Vietnam Veterans, and their families. We acknowledge that our nation has, in the past, not appropriately recognised their service and sacrifice. As we mark our century of [military] service, the Australian Government is determined to ensure that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past and honour those who have served their nation.

Some of these political remarks have sounded rather like dog-whistling about the importance of Australians being loyal to soldiers who are placed ‘in harm’s way’ today and in future; the implication seems to be that unpatriotic Australians were responsible for this ill-treatment in the past and might do something similar again to troops deployed today. (The current responsible Minister, Dan Tehan, seems less inclined to dog-whistling, preferring low-key announcements.)

The dog-whistling has played to attitudes present in at least some parts of the community, as evidenced by a letter to the editor of the Canberra Times this week which referred to ‘vile excuses for Australians’ who were alleged to have harassed soldiers returning from Vietnam. The 50th anniversary of Long Tan may see more of this type of reaction.

Perhaps, though, it is just the passing of time and the fading of memories that cements particular views in minds. The ‘welcome home march’ of October 1987 was seen then as making up for deficiencies in the welcomes provided while the war was on. ‘Fourteen years after the last Australian soldier returned from Vietnam’, said John Jesser in the Canberra Times, ‘the Australian community finally gave veterans of the war the welcome home they had been waiting for’. Twenty-seven years further on, Jesser’s Canberra Times colleague of 1987, Tony Wright, seemed to be following a similar track:

For the first time in Australian history, the nation’s troops received no universal embrace when they returned home. When that long war ended for Australia in 1972, Vietnam veterans were given no welcome home march. No cheering, no bunting. It left a legacy of bitterness and confusion that claimed more lives through alcoholism and suicide.

By 1987, the Hawke government judged enough time (15 years) had passed to deal with the Vietnam War. Australia was finally moved to welcome home its soldiers. In October 1987, 25,000 veterans, many of them weeping, marched through the streets of Sydney, with tens of thousands of Australians cheering them. (Emphases added.)

Welcome home parade, 6RAR, Brisbane, 14 June 1967, with 60 000 spectators (AWM P06136.013/Bruce Minell)

Welcome home parade, 6RAR, Brisbane, 14 June 1967, with 60 000 spectators (AWM P06136.013/Bruce Minell)

Wright’s piece was emotive but carefully written. There certainly was no big parade after 1972 – but there were fifteen parades between 1966 and 1972, one for all except one of the contingents returning from Vietnam and many of them witnessed by crowds far larger than that of 1987. The issues for many veterans, however, would have been ‘no parade after public opinion turned against the war, no parade after the Moratorium marches of 1970-71, no parade after it became clear that the war had been lost, no parade after those of us who had been there – and the government and most of the community – wondered whether it had all been worth it’.

Wright is also correct to draw attention to the effects of the war on those who fought it – alcoholism, suicide, the effects of Agent Orange, and so on. Despite politicians trying to divert attention, the deficiencies in dealing with these effects are best sheeted home, not to the public, who overwhelmingly supported the war till the early 1970s, but to government agencies, such as the Repatriation Commission and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, which were often sluggish in responding to veterans. Some RSL branches also were less empathetic than they could have been to men returning from Vietnam and to their families.

A complex war with complex fall-out

The complexities in the story of how Australian treated its Vietnam veterans were spelled out in Honest Honest History’s collection of materials last year entitled ‘Mythbusting about Vietnam: highlights reel‘. This collection drew upon the detailed research in books by Michael Caulfield, Mark Dapin, and official historian, Peter Edwards, which looked at evidence about parades, community reactions, RSL attitudes, the gradual move towards dealing with veterans’ trauma, particularly through counselling services under the auspices of DVA, and the phenomenon of ‘misremembering’.

A major legacy of the Vietnam War, still highly sensitive [Edwards wrote in 2014], concerns the impact on those who served, and by extension on their friends and families. This is a complex story, in which at least three major strands can be discerned: the reception given to the veterans by government agencies, such as the army, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (as the former Department of Repatriation had been renamed) and the Repatriation Commission, by ex-service organisations, and by the wider Australian community; the impacts, both direct and indirect, of post-traumatic stress on the post-war health of veterans; and the impact of a number of herbicides and other toxic chemicals, generally known collectively as Agent Orange.

Enduring myth: ‘The Welcome Home March, 3 October 1987: Because many men returned from Viet Nam in small groups it was not possible to have grand parades for them. When Battalions returned they usually marched through the streets of a major city but these often attracted the rabid rat bag element of the Anti War, Anti Conscription, Anti Government and Anti Anything crowd. Many Viet Nam vets were bitter about the treatment they received from an indifferent populace and an angry Rent A Crowd. Many still are.’ (Digger History: The page seems not to have been updated since 2006.)

Enduring myth: ‘The Welcome Home March, 3 October 1987: Because many men returned from Viet Nam in small groups it was not possible to have grand parades for them. When Battalions returned they usually marched through the streets of a major city but these often attracted the rabid rat bag element of the Anti War, Anti Conscription, Anti Government and Anti Anything crowd. Many Viet Nam vets were bitter about the treatment they received from an indifferent populace and an angry Rent A Crowd. Many still are.’ (Digger History: The page seems not to have been updated since 2006.)

It is around these intertwining strands that nuances need to be found; welcoming home has many aspects.

And the mythology about the war is even more intense [according to Michael Caulfield, writing in 2007]. Soldiers returning from Vietnam were attacked by organised anti-war protesters who spat at them, threw blood on them and called them “baby-killers”. No, they weren’t. Vietnam veterans are social misfits, loners, prone to alcoholism and violence. No, they’re not. Australians did not support the war. Yes we did, by a large majority until the last couple of years [of the war]. Australian soldiers were never welcomed home. Yes, they were. And on and on. The gap between veterans’ memories and popular belief about what Australia did in Vietnam, why we did it and even whether we succeeded, remains deep and wide and leaves most people either ignorant or confused. Even now, 40 years later, those two Vietnam Wars have never really come to terms with each other, never really been at peace. (Emphasis in original.)

The material in our collection drew responses from the Vietnam Veterans’ Federation and others and they are included again. There is also material included at the link above about the politics behind the building of the Vietnam Memorial in 1992.

Finally, there is some suggestion in the literature that Australian ‘memories’ were actually borrowed from what was said to have happened in the United States. This Wikipedia entry discusses American research on claims there that returning veterans were spat upon or called ‘baby-killers’.

Other ways of remembering

SBS earlier this year ran a show, The War That Made Australia, on the work of the Australian Army training team in South Vietnam and how its members later helped the resettlement of former South Vietnamese soldiers in Australia. The series should be available from SBS shelves in Dymocks stores.

Larry Zetlin wrangles a group of former draft resisters and opponents of the Vietnam War. A Facebook page (Hell No! We Won’t Go) links to interviews and reminiscences. There is expected to be a segment on Hell No! on 7.30 tomorrow evening (18 August). A set of interviews has been lodged with the Australian War Memorial (search the AWM website under ‘Hell No’).

Moratorium, Melbourne, 1970 (AWM P00671.009/Ron Gilchrist)

Moratorium, Melbourne, 1970 (AWM P00671.009/Ron Gilchrist)

Mick Armstrong wrote about the radicalisation of Australian university campuses during the Vietnam era. Echoes of this persist today. Paul Daley reviews Michael McKernan’s book, When This Thing Happened, about McKernan’s brother-in-law, Joe Stawyskyj, a disabled Vietnam veteran.

The variety of ‘after Vietnam’ experience underlines, if it was necessary, that there is always more to war than service and ‘sacrifice’. As an American peace group said last year, ‘One of the biggest concerns for us … is that if a full narrative is not remembered, the government will use the narrative it creates to continue to conduct wars around the world — as a propaganda tool’.

For more Vietnam-related material on the Honest History site, simply search under ‘Vietnam’.

David Stephens registered as a conscientious objector against the Vietnam War, one of the 1200 who did so. When his number was drawn out, and not being entitled to further educational deferment, he became a National Service Act defaulter. He took part in the first moratorium in May 1970.

17 August 2016 updated

Related article: A useful academic contribution is Nicholas Bromfield’s paper to the 2012 Conference of the Australian Political Studies Conference, ‘Welcome Home: reconciliation, Vietnam veterans, and the reconstruction of Anzac under the Hawke government’. Published later with a different title. Bromfield uses many references, including Ann Curthoys’ 1994 article pointing to the plethora of welcome home parades while the war was on. He focuses on indifference after the war turned sour as the key ingredient in veterans’ dissatisfaction and suggests the Hawke government’s neutralising of this dissatisfaction helped facilitate its promotion of the Anzac legend after the late 1980s. Bromfield has a perceptive article also from 2016 which concludes thus:

The Anzac resurgence so evident in the last quarter of a century has ensured that those prime ministers who do conform to the Anzac legend’s boundaries have a powerful rhetorical tool, if they are only talented enough to work within its limits and exploit its authoritative themes and sanctified tone. This gives succour to conservative views and little hope to those who would prefer to see a more progressive Anzac tradition, more representative of Australian diversity.

Related article from Bromfield on prime ministerial Anzac Day speeches.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.