The ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series

‘Divided sunburnt country: Australia 1916-18 (21): Australia reacts to the February 1917 Revolution in Russia: a look at newspapers of the day’, Honest History, 21 March 2017

Australia during the Great War was still remarkably insular. Australians’ view of the outside world was dominated by reports of the progress – or lack of progress – of the war. A notable exception – the interest in the Dublin Easter Rebellion of 1916 – could be attributed mostly to the Irish presence in Australia. (See earlier articles in our ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series.) To judge by their newspapers, Australians certainly responded to events in Russia in 1917, but they did so within fairly narrow parameters: for some Australians, the main question was what the revolution meant for the anti-German war effort; for others, it was much more about what it meant for socialism.

Czar Nicholas II and family (Daily Mail)

Czar Nicholas II and family (Daily Mail)

The details

The year 1917 saw revolutions in Russia in February (March in Australia; Russia did not adopt the Gregorian calendar till 1918) and October (November). The details of Russian events were slow to filter through to Australia; what was actually happening in Petrograd and Moscow was unclear.

Joan Beaumont sets the scene:

Although the Russian military leaders began 1917 full of fight, their home front was disintegrating. The development of heavy industry for munitions and war production had created a large industrial workforce in 1914–16, much of which had been drawn from peasants migrating to urban centres. But by 1917, the inflation of the currency, the dislocation of agricultural production and the inability of the railway system to adjust to multiple new demands meant that these workers could not translate their wages into food. They were hungry and angry, and in the winter months of 1916–17 they began rioting and looting in Petrograd.[1]

The World Socialist Web Site also has a handy summary:

By the winter of 1916-1917, the World War on the Eastern Front had brought Tsar Nicholas II’s armies to the verge of collapse. Casualties for the Russian Empire approached six million dead, wounded, missing and captured. The army was woefully undersupplied. Mutinies proliferated against an incompetent officer corps indifferent to the suffering of the overwhelmingly peasant army … [F]ood prices grew rapidly, provoking increasing social unrest.

Mainstream media, metropolitan and regional

News from Russia was slow. Even in early March 1917, there were still stories appearing about the assassination of Rasputin, which had occurred at the end of December, and the rejection by the Russian Duma (Parliament) in mid-December of peace terms from Germany. There were sketchy reports of food riots and other unrest and there was even a report on 13 March that the Czar had already abdicated a few days earlier.

The news that the Czar had really abdicated reached Australia on 16 March. Early interest was more in what happened next than in why the Revolution had occurred, although some newspapers had quite lengthy speculative discussions about recent events in Russia. There was some relief that the upheaval seemed to be relatively bloodless. There was even some sympathy for the Czar, who had a young family, including a sickly son.

One early (and hopeful) attempt to sum up where things were at came from the Daily Telegraph in Launceston on 19 March:

The news about the revolution in Russia continues to indicate very clearly that what has happened and is now being done at Petrograd and Moscow may be summed up as a domestic political disturbance, and that the effect of it so far as the war is concerned is much more likely to be an increase than a decrease of the great part that Russia has been taking in the conflict ever since hostilities began.

A Reuters cable was given prominence in the Portland Observer and Normanby Advertiser (19 March) and elsewhere: ‘The revolutionary movement came from the army as well as from people. There has never been any question of Russia getting war-weary. The revolution is a guarantee that the war will be waged with more intensified energy.’

Over the border in Narracoorte, South Australia, the leader writer in the Herald summed up the concern of many observers (20 March):

It is not yet clear how it will affect the war, but a domestic revolution in a country that is waging a war must be a great drawback. Nevertheless, it must appeal to all thinking people that it was better to have a revolution that shows where the Allies stand in the war with Russia [sic] than the state of affairs that have hitherto existed. Almost since the war began the Russian position in it has been an enigma, and it is hoped that the revolution has cleared the air in respect to the war.

Later and further west, in Adelaide, the Chronicle also seemed relieved (24 March): ‘The army is supporting the new Government, which is anti-German in character and favors the more vigorous prosecution of the war’. The Advocate in Melbourne (24 March), the voice of the Catholic Archdiocese, pointed out that, as the Duma (Parliament) seemed to be anti-German, its ascendancy would be an advantage for the war effort. ‘When the news came to hand that the Duma had forced the Czar to abdicate, the first feeling was that this might be the prelude to Russia arranging with Germany for a separate peace.’ Not so, now as the Duma was, indeed, anti-German.

The Sydney Sun was pleased to note (20 March) the report of the London Daily Chronicle‘s Petrograd correspondent ‘that the soldiers and workmen are solid for a victorious war. They receive indignantly speeches by revolutionary pacifists. A speaker who cried, “Down with the war” and spoke of our brothers, the Germans, was howled down by the Preobrahjehensky soldiers, shouting, “Bayonet him, brothers”.’

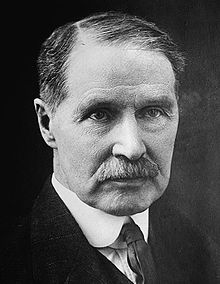

Bonar Law (Wikipedia)

Bonar Law (Wikipedia)

This would have been music to the ears of British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. ‘The British Government’, he was reported as saying, ‘hoped that the revolution would result in a closer union and more effective co-operation between Russia and its Allies’. The Wellington Times in New South Wales summarised (19 March) the view of British Foreign Secretary, Andrew Bonar Law, that the revolution ‘was not due to the desire for peace, but because the people were dissatisfied with the conduct of the war, and did not think it was being carried on with sufficient energy’.

Some Australians were keen to know more about the position in Russia, as this notice in the Bathurst Times of 20 March indicated:

The Revolution in Russia has burst upon most of us with startling suddenness. As it is not given to all to get even a glimpse behind the scenes of the doings in mighty Russia, [Anglican] Bishop Long’s lecture on the revolution on Thursday night in All Saint’s School Hall, at 8 o’clock, will be all the more welcome. No charge is being made for admission. All members of the community are invited to take this opportunity of getting some further light on an event of supreme importance and of some special significance at this time of crisis. A collection will be made.

There was a feeling in some quarters that the revolution had curbed German influence in Russia – the Czarina was German – and that it might be a lesson to the people of other empires. This appeared in the Riverine Herald of Echuca-Moama on 20 March:

If the revolutionary spirit can change Russia in a day from the most despotic form of Government into a Republic, there are hopes that the German people, trodden under as they are by militarism, may be nearer their own freedom and salvation and the world’s peace than we imagine.

Labour, socialist and feminist journals

In the organs of labour movement, socialist and feminist organisations, there was rather less about what the changes in Russia might mean for the prosecution of the war but considerable rejoicing at the overthrow of Russian despotism. In Direct Action, the organ of the Industrial Workers of the World, Tom Barker had this to say (31 March):

A mismanaged and bungled war, a corrupt and careless bureaucracy, and a rapid revolution of industry for war purposes acted as tinder to the spark of the strong and fearless revolutionary committees … Nicolai Romanov is only a citizen, now. His palace, and undisputed power is gone. The red flag of the people waves proudly from the towers.

In Brisbane, The Worker welcomed (22 March) ‘a revolution which, possibly, by its tremendous powers of international infection, may do more to advance the cause of the people than all social and governmental cataclysms which have preceded it in the history of the world’.

In Sydney, the International Socialist rejoiced (31 March) – ‘He, Nicolas, called the Tzar of Blood, couldn’t obtain money [to bribe the soldiers to kill the revolutionaries], because his regime was disastrous for the victorious ending of the present war’ – but wondered – ‘What will the workers of Russia get from this new power?’ Finally, in Melbourne, the Woman Voter complained (22 March) ‘we may not write as we would wish about the revolution in Russia’ (presumably due to censorship) and contented itself with reproducing extracts from the daily papers.

A fortnight later, however, the Woman Voter reported a meeting of the Socialist Party of Victoria at the Socialist Hall, Exhibition Street. The meeting resolved unanimously, as follows:

That this meeting of Socialists of Melbourne, in the spirit of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, expresses its unbounded elation with the magnificent Russian Revolution, and especially with the overthrow of the system of Despotic Government; and this meeting also records its deep and jubilant admiration of the work and martyrdom of the Socialist comrades in the Revolution, and in fraternally congratulating them on the wondrous and historical success of their noble efforts on behalf of the people, and the Red Flag sends international greetings, wishes them further glories of a proletarian character, assures them that the world is waiting on their victories, and believes that in due time complete working class emancipation will crown their great and epochal movement; and furthermore this meeting resolves to invite the Russian Consul in Melbourne to transit [sic] this message to Russia.

Reburial ceremony for Czar Nicholas II, St Petersburg 1998 (Daily Mail). The Czar and his family were assassinated in 1918.

Reburial ceremony for Czar Nicholas II, St Petersburg 1998 (Daily Mail). The Czar and his family were assassinated in 1918.

Moving on

It needs to be remembered also that, as it had been when the war began in 1914, Australia was in 1917 in the throes of a federal election campaign. What was unfolding in Russia would have been mere background noise for many Australians, particularly as the bitter conscription battles of 1916 were not long past. Hughes’s Nationalist government won the election on 5 May with a large swing against Frank Tudor’s rump Labor Party; much Australian domestic attention turned back to the problems of falling recruitment and what the re-elected government might do about it. As for Russia, Joan Beaumont summed up events after the departure of the Czar.

The provisional government that then assumed power remained committed to Russia’s continuing in the war, but there would be little serious fighting on the Russian front in 1917. Instead, virtually the whole of the country went on strike, the food crisis in the cities intensified and soldiers at the front mutinied. Progressively, the Soviets, the revolutionary committees established during the March revolution, gained the political ascendancy.[2]

Our ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series will take further glances at Russian events as they were perceived in Australia.

[1] Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2013, Kindle Locations 4581-85).

[2] Beaumont, Kindle Locations 4586-89.