‘Donnelly-Wiltshire gunners fire a civilised salvo – but will Minister Pyne follow up?’ Honest History, 15 October 2014 and updated

If history was as predictable as the history curriculum recommendations of the Donnelly-Wiltshire report we would have no need of the discipline at all. This is what the reviewers came up with as their recommendations under the heading ‘History’.

Australian Curriculum: History should be revised in order to properly recognise the impact and significance of Western civilisation and Australia’s Judeo-Christian heritage, values and beliefs.

Attention should also be given to developing an overall conceptual narrative that underpins what otherwise are disconnected, episodic historical developments, movements, epochs and events.

A revision of the choice available throughout this curriculum should be conducted to ensure that students are covering all the key periods of Australian history, especially that of the 19th century.

The curriculum needs to better acknowledge the strengths and weaknesses and the positives and negatives of both Western and Indigenous cultures and histories. Especially during the primary years of schooling, the emphasis should be on imparting historical knowledge and understanding central to the discipline instead of expecting children to be historiographers. (p. 181 of pdf)

Moses in the bulrushes (Flickr Commons/Eve and Her Daughters of Holy Writ or Women of the Bible, published 1861)

The report was delayed, much anticipated and, at last, released and reported in detail in, for example, The Australian and The Age – after it was earlier leaked to the Sunday Telegraph – and on the ABC. The coverage in The Age was less comprehensive than that in The Australian, where the phrase ‘back to basics’ (also used by the prime minister) bulked large and the presentation, reflecting the paper’s long-standing interest in the issue, had an air of ‘we deliver’, in contrast with The Age‘s rather downbeat tone.

There was also thoughtful commentary in The Conversation (180 comments), on RN Breakfast, in the Australian Independent Media Network (103 comments), again in The Conversation, in Inside Story and Tony Taylor in the Sydney Morning Herald. The Guardian Australia got in early, then went again about the lack of evidence in the report for the failings claimed. In his initial press conference about the report Minister Pyne resisted challenging ‘the Left’ to a stoush in the way he did when all of this began more than 12 months ago (history) and, indeed, he made a point of playing down ideological issues. The Minister also appeared on Lateline.

There is, of course, much, much more in the 300 page report than the parts dealing explicitly with the teaching of history. Other commentators will examine the validity of the proposals regarding curriculum overcrowding, the importance of phonetics, getting back to basics, cross-curriculum priorities – especially whether the approach proposed will raise or reduce their profile – the future role of the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) and so on, but this note focuses on the teaching of history.

The key pages in the report regarding history are pages 176-181, though there is a bit more in chapter 6, too. (We hope to look in depth later at the supplementary material and the material on civics education.) There is precious little evidence in pages 176-181 which comes from the reviewers’ assessments of the existing curriculum or from relevant literature. Instead, there is a brief selection of extracts from submissions received. These extracts are basically a shoot-out between, on the one hand, people who want more Christian values taught and, on the other, history teachers’ associations who reckon things in the curriculum are pretty much OK as they are.

The reviewers support the view, expressed particularly by University of Wollongong historian Gregory Melleuish, that there is a body of ‘essential historical knowledge’ that students need to absorb. This approach to history has interesting implications, especially when read together with the concluding phrase in the recommendations above about not expecting children – particularly at the primary level – to be historiographers. The American educator, David Turnoy, has noted the importance of a child’s initial introduction to history: the first view strongly influences later encounters with the subject. Turnoy’s remarks are particularly relevant to how children are taught about war – a sanitised introduction colours later impressions – but they have broader relevance. It may be that a ‘just the facts’ start in history permanently blunts the capacity for ‘historiography’ – which we take to be asking questions, sifting evidence and weighing alternative interpretations.

Moving on, the reviewers come down on the side of the submitters who believed the cross-curriculum priorities (sustainability, Australia’s engagement with Asia, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures) in the curriculum tend to drive out the adequate consideration of Western civilisation and Judeo-Christian heritage and values and beliefs. The reviewers feel that the current curriculum gives the latter a bad wrap but deals too fully with the cross-curriculum material, particularly with Indigenous history and culture.

After continuing a little further with this argument about the effect of the cross-curriculum priorities and how this subject matter could be better dealt with, the reviewers conclude with an endorsement of Associate Professor Melleuish’s views about narrative history. Melleuish wants ‘a more structured historical narrative to underpin what, at times, appears to be disconnected “things to know about the past”‘. It is not spelled out explicitly but one gets the impression that ‘Western civilisation’ is intended to fit the bill as the underpinning narrative.

We have already noted that there is in the report an aversion to historiography, especially for younger children but generally also. This apparent wariness about asking historical questions can be read in conjunction with the trope about Western civilisation. Is there a yearning to use history classes to bolster a particular way of looking at what got us to where we are today? If so, why?

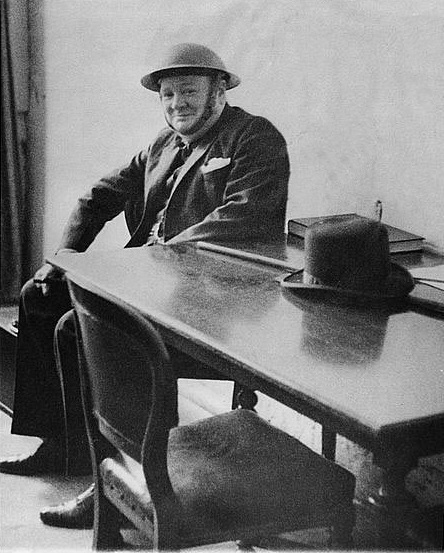

To get at the answer to that question, we need to look more closely at this concept of Western civilisation, which is given such prominence and which, the reviewers tell us, should get more of a run in the curriculum. Western civilisation is an elusive concept. In some respects it seems pretty much a one-track phenomenon. The present writer sometimes characterises it in public presentations as a continuous single thread from Moses in the bulrushes through Jesus Christ to William the Conqueror, William Shakespeare and Good Queen Bess, the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Queen Victoria, ANZAC (always in upper case), Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia, Don Bradman, Winston Churchill, Robert Menzies and John Howard to the present day.

This is perhaps a little unfair but it conveys the general idea that there is a single, received version of history, linked with a set of facts that need to be learnt to ensure patriotic soundness and an understanding of what it means to be Australian. In Melleuish’s terms, if we read him correctly, Western civilisation is the glue which holds the facts together. This version of history is presented as an essential part of the civic education of young Australians, which will help ensure that we continue in future generations much as we are seen to have been in the past. Put another way, to ensure that those who come across the seas join us but do not try to change us. Western civilisation offers a template for the Australia of the future, as our activities generate new facts for future students to absorb.

Where does this Western civilisation concept come from? It may be in the DNA of some of us by birth or persuasion but it is also cut from the whole cloth of the Institute of Public Affairs. Christopher Pyne has been closely associated with the IPA’s program Foundations of Western Civilisation since at least 2011 and has clearly seen the national curriculum as a crucial battleground. The IPA’s Western civilisation program ‘prospectus’ is a paean of praise for this concept and a lament for what we are seen to have lost.

The Australian nation has benefitted enormously from the Western legacy. However, this legacy is largely absent from our understanding of our history. Australian history is taught to students as a series of episodes, from the arrival of the Aboriginal peoples, to white settlement, and then to a disconnected series of social movements.

Our history is taught as the history of the Australian continent, rather than of the Australian nation and society. Modern Australia is founded on principles established in Europe over centuries, but democracy, civil society, economic freedom, and religious pluralism are presented as if they suddenly emerged at Botany Bay.

Australia has not always been so culturally forgetful. In 1871, the historian and biographer John Morley wrote that there were three books on every Australian squatter’s shelf – the Bible, Shakespeare, and Macaulay’s Essays. The difference with today is stark. Australians now have limited historical knowledge, particularly of British and European history. This lack of understanding undermines the legacy of Western Civilisation, and, ultimately, impoverishes the nation.

There are a couple of comments that can be made on these paragraphs. First, of course, Western civilisation is an important part of Australia’s historical heritage, just as Anzac is. (Honest History’s unofficial motto, Not only Anzac but also …., makes the latter point clear.) When broadened out from a single thread to a canon of literature – as the IPA publication 100 Great Books of Liberty does – it gathers considerable ballast and lots of reading matter. The values of Western civilisation are for the most part admirable and not confined to the West: some of them are universal, others nicely complement the values that come from other, non-Western, traditions.

It diminishes us, however, to bulk up one strand of our history at the expense of others, whether the bulked-up strand is Western civilisation writ large or Anzac on steroids. Just as we are a more interesting civilisation than one that deifies bronzed larrikin soldiers we are a more vital community than one that yearns for well-thumbed copies of Macaulay. There are more diverse and imaginative ways of bolstering Australians’ lack of historical knowledge than by administering a stiff dose of ‘Western civilisation’. Moving us in more imaginative directions is what Honest History, in a modest way, is attempting to do.

Secondly, values, whether democracy, civil society, economic freedom, religious pluralism – the IPA’s list – or any others are best imparted mostly as civics education rather than in history classes. History classes might note the importance of these values and point to examples of them being practised or threatened but these classes should not be the main place for inculcating them. We have written separately about the welcome change in the Simpson Prize (the essay competition for Year 9 and 10 students) from civics education to asking proper history questions, which require the collection of evidence and the consideration of causes. We concluded that study with these words:

[C]ivics education should be separated from the teaching of history. History is – or should be – about contesting, evidence-based interpretations. Civics education is about inculcating particular behaviours. Civics education and history do not belong in the same timetable slot.

What has the Minister said in response to the Donnelly-Wiltshire review? His initial press conference remarks touched on the overcrowding of the primary curriculum and the practicalities of ‘fitting in’ cross-curriculum priorities but hardly mentioned Western civilisation. He continued in this vein. He made a point of saying the national curriculum was generally sound. He did not repeat his earlier complaints that Anzac Day got insufficient weight in the curriculum compared with other ‘days’ – perhaps because he had been briefed that the evidence for such complaints is lacking. The interim government response was similarly bland and general and suggested more work was needed by ‘educational experts’ on ‘rebalancing’ the curriculum.

So, there is a strong hint of ‘hasten slowly’ – at the ministerial level, at least. To use an apposite metaphor, the wheels on the school bus will continue to go round and round. While ministers are to meet in December, the Minister said on ABC radio that any changes would not be in place till 2016 and that implementation was essentially a matter for the states and territories. Some commentators felt the review report was more balanced than expected while others thought it was a fizzer, after all the hype and foreboding.

There is plenty apart from the explicitly history parts of the agenda to keep the minister and his colleagues occupied. Western civilisation has been around for a while (see above regarding bulrushes); perhaps there is a feeling that it can afford to bide its time. There may be, however, some grenades lurking in the Melleuish obiter dicta and the supplementary material.

Meanwhile, the IPA media release claimed the report marked the beginning of the end of the ‘biased and sub-standard’ national curriculum. The release gave prominence to the material in the report about the curriculum’s failings in regard to Western civilisation and Judeo-Christian heritage. ‘This confirms IPA findings that the National Curriculum distorts the past for ideological purposes. The Review exposes the National Curriculum for what it really is: politically biased, superficial and lacking in academic rigour …’. This is a rather more feisty view than the report takes but it suggests that the history curriculum bus ride is far from over; the IPA passengers are still looking for value for their ticket. (A longer response from the IPA canvasses other issues, as well.) Honest History will be observing the journey with interest.

Update 18 January 2015: readers may wish to refer to Dr Donnelly’s article from October 2014 on how a common curriculum generates common values and an earlier article from Professor Tony Taylor comparing history curriculum battles in a number of countries.

The exchange also reminds me of my Primary, Junior High, High School and University history and civics studies in America from 1957 thorough 1973. Initially a student would only be given “Civics” and “Social Studies” classes which touched upon History. “Civics” being short for “Citizenship” and would seem generally to be something similar to what the IPA is aiming for as its ideal Australian school curriculum. “Civics” mainly focused on the National History of the U.S. (as categorized and sliced up by the various Presidential terms) with a lot of attention paid as to how the political system worked and how it evolved and what your “place” in it was as a citizen. Slight attention was given to the two hundred year period before the independence of the country following the noticing of it by Europeans (Columbus, Pilgrims, Thanksgiving, a few Indians and explorers being mentioned — before the focus on the run-up to Independence). Even less attention was given to the millennia before 1492. It was a curriculum that stepped very softly when dealing with anything that might at all be seen as tending to cast a shadow on what was “good” about America.

In High School, we then had a choice of U.S. History (which took a whole year to complete, and even then never covered up to the present) which was a somewhat expanded version of “Civics” but, again, rarely delved into controversial aspects of American history. For example, only the “Patriot” side of the Revolutionary War was dealt with in-depth. The “Loyalist” view of the conflict was summarily dismissed (pretty much the script of Mel Gibson’s later Revolutionary War film). A High School student with enough interest could also take the optional “World History” course at some point in his or her last two years (Junior or Senior) but that was a one semester course and, naturally, you never got up to the present.

It was only when majoring in History in University that anything like a more balanced view of the past could be accessed. As one example, again regarding the Revolutionary War, the impression given through High School to students was that the majority of British settlers in 18th century America were ardent supporters of the move for independence from Britain. Only in University would such studies as that purporting to show that twenty-five percent were supporters of the break, twenty-five percent were wanting to remain British and about fifty percent didn’t care, just wanting to get on with their lives.

Such expanded aspects give students entirely different “complications” to ponder. Something the IPA in Australia nor the Tea Party Republicans in America would be in favor of in this day and age.

Very interesting exchange. Even if it causes me to shudder with the baleful, lurking IPA presence.

Greg: thanks for dialogue. The link above to the piece by Stuart Macintyre has a bit more on the world history angle, I recall. As for the IPA list, if someone passes it on to us or points us to where it can be found we will gladly highlight it. BTW we are working on the spellchecker. David Stephens

Could I just conclude with a couple of observations as follows:

1. The history curriculum claimed to be putting Australian history in the context of world history. Unfortunately no world historian would recognise the curriculum as world history as it exists in 2014. If it is not world history then it should not be described as such.

2. The IPA did a fact check on some of the textbooks produced for teaching the curriculum and found a large number of basic factual errors, such as wrong dates.

These surely must be a concern for anyone interested in Honest History.

Apologies for not responding earlier to Greg Melleush’s previous post. I guess my problem lies in the search for a binding narrative, whether it is Western civilisation or world history or world history with the West as the main ingredient or even ‘foragers to Facebook’. I’m nervous about central narratives just as I’m nervous about foundation myths. I’ve got no great problem really with a history that lacks a narrative or a theme, that is ‘disconnected, episodic historical developments, movements, epochs and events’. Churchill’s probably apochryphal themeless pudding may have been quite palatable to other diners at whatever club he was dining at. Evidence is the thing. David Stephens

Oh Dear! I should point out that this website has a spell check. Hence when I wrote practise in my original submission it underlined it in red. (It’s doing it again!) When I changed it to practice it ceased to do so. If it was practice you wanted rather than practise then I was happy to oblige.

Stuart Macintyre of the University of Melbourne has provided this comment:

Thanks, David. I think you treat the report well.

I’ve not yet read Greg Melleuish’s full submission (though I note in his first comments he confuses practice and practise). As you say in your account, the section of the report that deals with History simply summarises and paraphrases a number of submissions, and gives no reasons for its decision that Western civilisation and the Judeo-Christian tradition need to be strengthened.

If it were a student essay, the authors would be told to go away and do it again, this time explaining the basis of their judgements. They would be reminded that a critical inquiry has to go beyond scissors and paste to proper engagement with the issues.

It is also remarkable that the report fails to explain the structure of the curriculum and the principles that guided it.

(Original email available. See also Professor Macintyre here: https://honesthistory.net.au/wp/macintyre-stuart-launch-of-holbrooks-anzac/.)

Actually, the status of the curriculum as world history is absolutely crucial. It claims to be placing Australian history in a world history framework. It clearly fails to do this. It does not understand what world history means. The problem with the existing curriculum is that with so much emphasis on the depth studies, and the idiosyncratic nature of the way in which the depth studies have been selected, students could easily end up with a very strange view of the past. In short, there appears to be no ‘glue’ tying the structure together. By no means do I suggest that ‘Western civilisation’ be the master narrative. For example, I would like to see more of China in the curriculum but we need to have a principle which guides students. One crucial theme of a world historical approach is the growth of contact among the various peoples of the world. That said, it must also be seen that the crucial factor in world history since about 1750 was the growth of Western dominance and its consequences. For our students, it must be about Australia, the West and the world, and given that not everything can be studied, working out how to get the balance right, and what to put in and what to leave out. But we cannot do that unless we have some guiding principles, which are clearly lacking in the curriculum as it is.

Fair point though I note that in paragraph 5 I referred to further work we hope to do on the supplementary material and in paragraphs 8, 11 and 18 I was equivocal because it was not clear to me on the basis of the six pages exactly what was being said. I look forward to reading further. That having been stated, however, it does not seem to me that whether the curriculum qualifies as world history goes to the point about a bulked-up Western civilisation not being a prescription for improved history teaching. But again I look forward to reading further about how Western civilisation fits a broader context. David Stephens

If one wishes to practice ‘Honest History’ it is necessary to read the documents and not to rely on summaries of them. From the above account it is clear that David Stephens has not actually read my review of the History Curriculum which is included in the Supplementary material. If he did he would discover that much of the discussion relates to the issue of whether this curriculum can be actually described as world history (the answer is no). I can write as someone who has published peer reviewed material in the area of World History. He will also discover that I describe it at one point as Eurocentric. The whole point about the study of the West is that it can only be understood when it is studied in the framework of the wider history of humanity. The ‘glue’ which holds the facts ‘together’ is the transformation of humanity from foragers 10,000 years ago to the sort of world in which we live today.

I would make a plea that before individuals jump into making judgements, most of which they have made in advance of reading the relevant documents, that they actually READ the documents. That is the foundation of any study of history.